The emission of light in a hydrogen atom occurs when an electron transitions from a higher energy level to a lower one. The energy difference between these levels is calculated using the Rydberg formula: \( E = R_H \left( \frac{1}{n_1^2} - \frac{1}{n_2^2} \right), where \( R_H \) is the Rydberg constant, \( n_1 \) is the lower energy level, and \( n_2 \) is the higher energy level. The wavelength of the emitted light is inversely proportional to the energy difference. This relationship is given by the equation \( \lambda = \frac{hc}{E}, where \( h \) is Planck's constant and \( c \) is the speed of light.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Emission of light | Occurs when an electron transitions from a higher energy level to a lower energy level |

| Energy difference | Given by the Rydberg formula: \(E = R_H \left( \frac{1}{n_1^2} - \frac{1}{n_2^2} \right)\), where \(R_H\) is the Rydberg constant, \(n_1\) is the lower energy level, and \(n_2\) is the higher energy level |

| Wavelength of emitted light | Inversely proportional to the energy difference: $ \lambda = \frac$ , where \(h\) is Planck's constant and \(c\) is the speed of light |

| Shortest wavelength | Corresponds to the largest energy difference |

| Example | If the \(n = 5\) to \(n = 2\) electron transition in a hydrogen atom occurs at 434 nm, violet is in the range of visible light |

Explore related products

$10.67

$12.13

What You'll Learn

Emission of light in a hydrogen atom

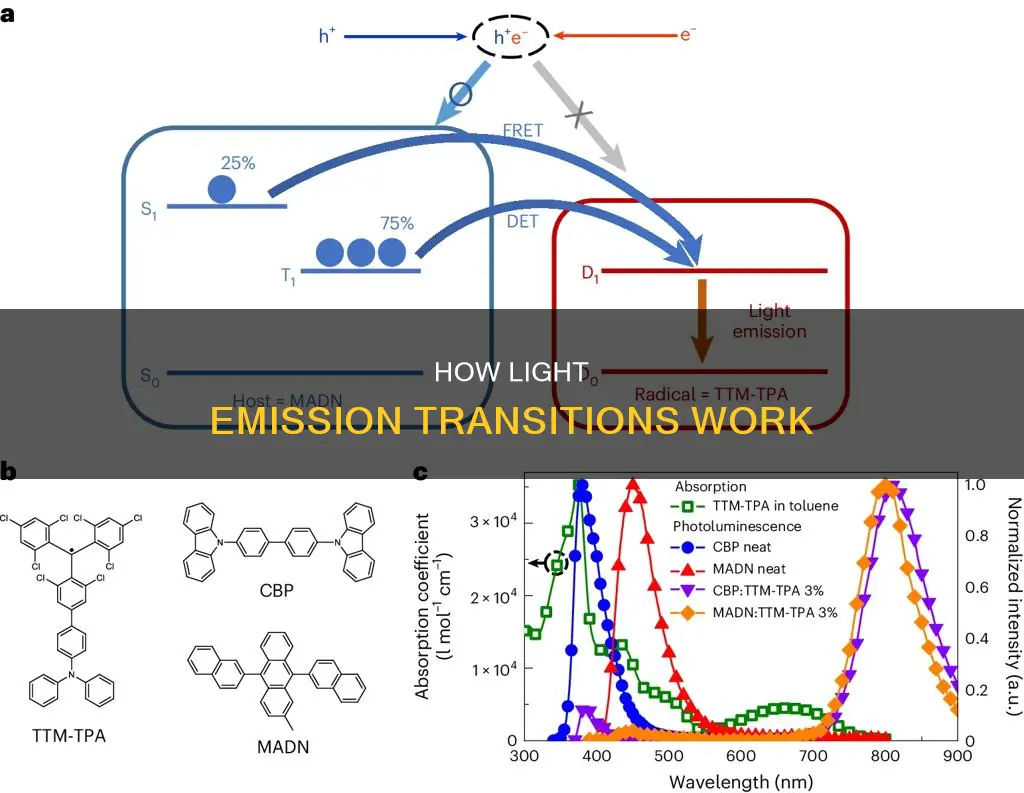

The emission of light in a hydrogen atom is a consequence of the transition of an electron from a higher energy level to a lower energy level. The hydrogen atom is a single-electron atom, with one electron attached to the nucleus. The energy of the atom is dependent on the energy of the electron. When the electron changes levels, the atom's energy decreases, and it emits photons of light. The wavelength of the emitted light corresponds to the change in energy levels, with the distance of the drop determining the wavelength and energy of the photon.

The emission of light from hydrogen atoms can be observed when an electric current is passed through a glass tube containing hydrogen gas at low pressure. This causes the tube to emit blue light. When this light passes through a prism, four narrow bands of bright light are observed, each with a distinct wavelength and colour. These bands are the result of electrons in the hydrogen atom transitioning between different energy levels.

The Bohr model of the atom explains the emission of light from hydrogen atoms. According to this model, electrons revolve around the nucleus in circular orbits or energy levels. When an electron moves from a higher energy level to a lower one, it emits a photon of light with a specific wavelength and energy. The equation derived from the Bohr model successfully predicts the wavelength of the emitted light when an electron falls from a higher energy orbit to a lower one.

The Schrödinger model, on the other hand, assumes that the electron is a wave and describes the regions in space, or orbitals, where electrons are most likely to be found. This model provides a mathematical description of the distribution of electrons in an atom using wave functions. However, it is more challenging to visualise physically compared to the Bohr model.

In summary, the emission of light in a hydrogen atom occurs due to transitions of electrons between different energy levels. The specific wavelength and colour of the emitted light depend on the change in energy levels of the electron. The Bohr and Schrödinger models offer different explanations for these electron transitions and the resulting emission of light in hydrogen atoms.

Exploring the Mesopelagic and Deep Sea: Understanding the Unknown

You may want to see also

Electron transition from higher to lower energy levels

Electrons are negatively charged particles that orbit the nucleus of an atom. These orbits are called shells, and each shell is associated with a specific energy level. The energy level of an electron depends on its distance from the nucleus, with electrons closer to the nucleus having lower energy levels due to their stronger interaction with the nucleus. Bohr named these orbits as K (n=1), L (n=2), M (n=3), and so on, in ascending order of distance from the nucleus.

Electrons can transition between different energy levels. To move to a higher energy level, an electron must absorb energy, typically in the form of a photon. Conversely, when an electron transitions from a higher energy level to a lower one, it releases energy. This energy release occurs in the form of light energy, specifically as a photon. The energy of the emitted photon is equal to the energy difference between the initial and final states of the electron.

The wavelength of the emitted light is inversely related to the energy difference between the energy levels. A larger energy difference corresponds to a shorter wavelength, and vice versa. This relationship is described by the Rydberg formula:

> \( E = R_H \left( \frac{1}{n_1^2} - \frac{1}{n_2^2} \right) \)

Where \( R_H \) is the Rydberg constant, \( n_1 \) is the lower energy level, and \( n_2 \) is the higher energy level.

The type of light emitted during electron transition depends on the specific energy levels involved. For example, an electron transitioning from n≥2 to n=1 emits ultraviolet light, known as the Lyman series. On the other hand, an electron transitioning from n≥3 to n=2 emits visible light, referred to as the Balmer series.

In summary, electron transitions from higher to lower energy levels result in the emission of light in the form of photons. The characteristics of the emitted light, such as its wavelength and type, depend on the energy difference between the initial and final energy levels of the electron.

Understanding Severe Pain Criteria in OASIS M1242

You may want to see also

Rydberg formula and energy levels

In 1890, Rydberg proposed a formula describing the relation between the wavelengths in spectral lines of alkali metals. He noticed that these lines came in series and he could simplify his calculations using the wavenumber as his unit of measurement. The wavenumber is the number of waves occupying a unit length, equal to the inverse of the wavelength (1/λ).

Rydberg plotted the wavenumbers (n) of successive lines in each series against consecutive integers representing the order of the lines in that series. He found that the resulting curves were similarly shaped, and he sought a single function that could generate all of them when appropriate constants were inserted.

The Rydberg formula can be written as:

> {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{\lambda _{\mathrm {vac} }}}=R_{\text{H}}\left({\frac {1}{n_{1}^{2}}}-{\frac {1}{n_{2}^{2}}}\right),},

Where λvac is the wavelength of electromagnetic radiation emitted in a vacuum, RH is the Rydberg constant for hydrogen, and n1 and n2 are the principal quantum numbers of the two orbitals.

This formula can be extended for use with any hydrogen-like chemical elements:

> {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{\lambda }}=RZ^{2}\left({\frac {1}{n_{1}^{2}}}-{\frac {1}{n_{2}^{2}}}\right),},

Where Z is the effective nuclear charge.

The Rydberg formula can be directly applied only to hydrogen-like or hydrogenic atoms, i.e., atoms with only one electron being affected by an effective nuclear charge. Examples include He+, Li2+, and Be3+, where no other electrons exist in the atom.

For an electron in a hydrogen atom, characterized by the quantum numbers n, l, and m, the electron should, in principle, remain in that state indefinitely. However, if the state is slightly perturbed, such as by interaction with a photon, the electron can transition to another stationary state with different quantum numbers.

The energy change of the electron during this transition is given by:

> {\displaystyle {\mit\Delta} E = E_0\left(\frac{1}{n_f^{\,2}}-\frac{1}{n_i^{\,2}}\right).}.

If ΔE is negative, the electron emits a photon, and if ΔE is positive, the electron absorbs a photon.

The Rydberg formula provides the possible wavelengths of photons emitted by a hydrogen atom as its electron transitions between different energy levels:

> {\displaystyle \frac{1}{\lambda} = R\left(\frac{1}{n_f^{\,2}}-\frac{1}{n_i^{\,2}}\right),},

Where λ is the wavelength, R is a constant, and nf and ni are the final and initial quantum numbers, respectively.

The Rydberg formula reflects the underlying simplicity of the behavior of spectral lines in terms of fixed (quantized) energy differences between electron orbitals in atoms.

Understanding the Constitution: Why and How to Read It

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Wavelength and energy difference

The emission of light in a hydrogen atom occurs when an electron transitions from a higher energy level to a lower one. The energy difference between these two levels can be calculated using the Rydberg formula:

> E = RH * (1/n_1^2 - 1/n_2^2)

Where E is the energy difference, RH is the Rydberg constant, n1 is the lower energy level, and n2 is the higher energy level.

The wavelength of the emitted light is inversely proportional to the energy difference. This relationship is described by the equation:

> λ = hc/E

Where λ is the wavelength, h is Planck's constant, c is the speed of light, and E is the energy difference.

As the energy difference increases, the wavelength of light decreases. This means that transitions with a larger energy difference will result in light with a shorter wavelength.

The energy of a photon is directly proportional to its frequency and inversely proportional to its wavelength. This means that photons with higher frequencies and shorter wavelengths have higher energy. The photon energy can be calculated using the equation:

> hc/e = photon energy in electronvolts

Where h is the Planck constant, c is the speed of light, and e is the elementary charge.

The units commonly used to express photon energy are electronvolts (eV) and joules. One electronvolt is equal to 1.602176634 x 10^-19 joules. Photon energy can also be calculated using the wavelength in micrometers.

The Electoral College: Democracy's Friend or Foe?

You may want to see also

Planck's constant and speed of light

Max Planck's work on the equations of motion for light led to the discovery of the Planck constant, denoted as 'h'. Planck's work showed that the spectral radiance per unit frequency of a body at frequency ν and absolute temperature T is given by the Planck constant. This constant is a fundamental part of quantum theory, signifying that physical action is restricted to integer multiples of a very small quantity, the "elementary quantum of action".

The Planck constant is also related to the energy of light, with Einstein proving that light energy is transferred in small "packets" or photons, whose size is the same as Planck's "energy element". This led to the modern version of the Planck-Einstein relation.

The Planck constant is one of five fundamental physical constants that are equated to 1 to derive Planck units. These are:

- The speed of light

- Boltzmann's constant

- Coulomb's constant

- Newton's constant

- Planck's (reduced) constant

By equating these constants to 1, we can derive five Planck units:

- Planck length unit

- Planck time unit

- Planck mass unit

- Planck energy unit

- Planck charge unit

The speed of light is an important factor in understanding the Planck constant, as it is one of the fundamental constants used to derive the Planck units. The speed of light is also related to the concept of photon energy and the relativistic length contraction effect, which states that photons are dimensionless and travel at the speed of light.

The Roman Constitution: Power, Checks, and Balance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The emission of light occurs when an electron transitions from a higher energy level to a lower one.

The energy difference between the two levels can be calculated using the Rydberg formula: E = RH(1/n_1^2 - 1/n_2^2), where RH is the Rydberg constant, n1 is the lower energy level, and n2 is the higher energy level.

The wavelength of the emitted light is inversely proportional to the energy difference and can be calculated using the formula: λ = hc/E, where h is Planck's constant and c is the speed of light.

To find the transition with the shortest wavelength, identify the transition with the largest energy difference, as a larger energy difference corresponds to a shorter wavelength.