Aerosols are suspensions of fine solid particles or liquid droplets in the air or another gas. They can be classified according to their physical form and how they are generated, including dust, fume, mist, smoke, and fog. The size of aerosol particles plays a crucial role in their properties and potential health hazards. Fine particles with a diameter smaller than 2.5 μm can reach the gas exchange region in the lungs, posing risks to human health. Atmospheric aerosols are categorized into six groups by NASA/AERONET, including biomass burning, rural, continental pollution, dirty pollution, desert dust, and polluted marine. These classifications are based on the composition and source of the aerosols. Various techniques, such as stereoscopic and spectroscopic methods, are employed to study aerosol properties and their impacts on the Earth's climate.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Aerosol particle size

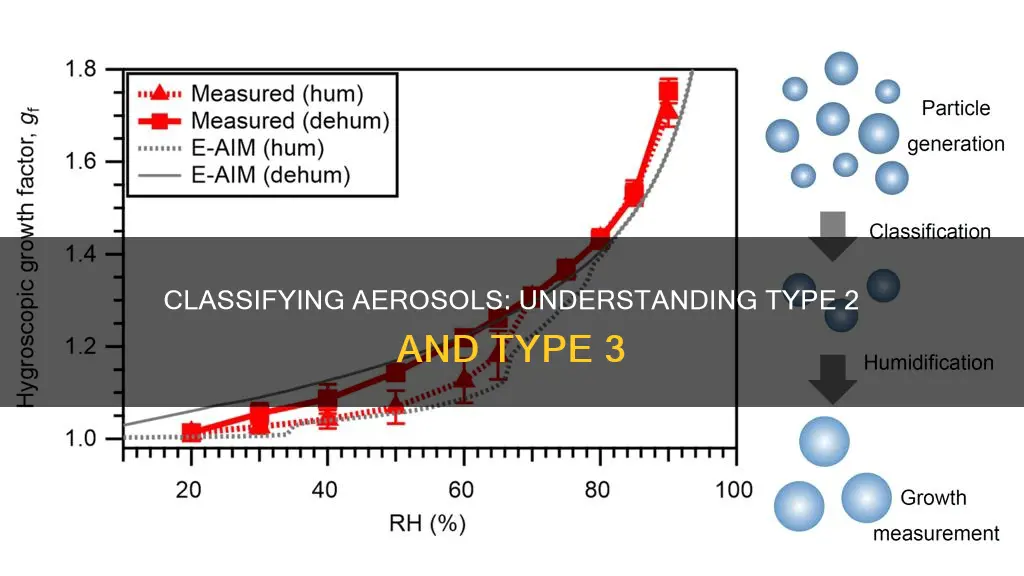

The measurement of aerosol particle size is a complex task, especially for volatile and dynamic aerosols like those produced by e-cigarettes. Evaporation and coagulation can impact the accuracy of measurements. To address these challenges, researchers have developed a low-flow cascade impactor system that minimises the effects of evaporation and coagulation during the measurement process. This system has been successfully used to study the parameters affecting aerosol particle size.

In the field of health and safety, understanding the size of ultrafine aerosol particles is crucial. Ultrafine aerosols, with particle sizes ranging from 1 to 5 nm, can influence the accuracy of cascade impactor measurements. By using mesh screens or diffusion batteries, the impact of ultrafine particles can be minimised during aerosol sampling. Additionally, the toxicity and health effects of ultrafine particles have been a subject of extensive discussion.

The dispersion of aerosols in indoor environments, such as concert halls and seminar rooms, is another area of interest. Experiments have been conducted to estimate the infection risk by assessing the behaviour of virus-laden aerosols, including their spreading, mixing, and removal by air purifiers. Non-hazardous surrogate aerosols, such as salt particles, are used in these experiments to mimic the behaviour of virus aerosols. High particle concentrations are advantageous in minimising the influence of background aerosol concentrations, but proper consideration of aggregation and settling is necessary for accurate results.

Furthermore, Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations and experimental investigations have been employed to study the spatial dispersion of aerosols and the effectiveness of ventilation systems in reducing airborne transmission of pathogens. These studies provide valuable insights into the complex behaviour of aerosol particles and their impact on various environments.

Understanding Duty Fees on Manufactured Goods

You may want to see also

Natural vs human-caused aerosols

Aerosols are tiny particles suspended in the atmosphere. They are often invisible to the human eye, but they significantly impact climate, weather, health, and ecology. Aerosols come from both natural and human-made sources, and sometimes both. Natural aerosols include dust, sea salt, smoke from wildfires, and volcanic ash. Human activities, such as burning fossil fuels, agricultural practices, land clearing, and waste incineration, have increased the amount of aerosols in the atmosphere, with complex effects on the planet.

Natural Aerosols

Natural aerosols, such as dust, sea salt, and volcanic emissions, have existed long before human civilization. Dust, for instance, is scoured from deserts, dry riverbeds, and lakebeds, and its concentration in the atmosphere varies with climate. Sea salts are natural sources of aerosols, whipped out of the ocean by wind and sea spray, typically occupying the lower parts of the atmosphere. Wildfires and volcanic eruptions release smoke, ash, and sulfate particles into the atmosphere, which can reach the upper atmosphere and remain suspended for months or years. These natural aerosols play a role in shaping climate and weather patterns.

Human-caused Aerosols

Human activities have significantly contributed to the increase in aerosols in the atmosphere. The burning of fossil fuels, including coal, oil, and gas, releases fine particles that contribute to air pollution and pose risks to human health. Industrial activities, such as factory emissions, power plants, and automobile exhaust, have also released human-made aerosols. These particles, including black carbon, ozone, and sulfate droplets, have complex effects on the planet's climate. While some aerosols warm the Earth's atmosphere, others cool it. Additionally, human activities have altered the natural cycle of dust, making some places dustier and affecting regional climates.

Health Impacts

Aerosols have clear and significant impacts on human health. Fine particulate matter in the air can irritate the lungs, cause respiratory damage, and lead to lung diseases. Chronic exposure to these particles is associated with decreased life expectancy, higher risks of lung cancer, and adverse effects on cardiovascular health. The health risks are particularly prominent in urban areas, with China and India facing some of the most severe consequences. Overall, human activities have increased the total amount of particles in the atmosphere, leading to increased air pollution and negative health outcomes.

European Reactions to the Ottoman Constitution of 1876

You may want to see also

Atmospheric aerosols

An aerosol is a suspension of fine solid particles or liquid droplets in the air or another gas. They can be generated from natural or human causes. Aerosols can be classified according to their physical form and how they were generated, including dust, fume, mist, smoke, and fog. Several types of atmospheric aerosol have a significant effect on Earth's climate. These include volcanic, desert dust, sea salt, biogenic, and human-made aerosols.

Volcanic aerosols, for instance, are formed in the stratosphere after an eruption as droplets of sulfuric acid. These aerosols can remain in the atmosphere for up to two years, reflecting sunlight and lowering temperatures. Desert dust, on the other hand, consists of mineral particles blown to high altitudes, where they absorb heat and may inhibit storm cloud formation. Human-made sulfate aerosols, primarily from burning oil and coal, also influence cloud behaviour.

According to NASA/AERONET data, atmospheric aerosols can be classified into six categories: biomass burning (BB), rural (RU), continental pollution (CP), dirty pollution (DP), desert dust (DD), and polluted marine (PM). Biomass burning is an aged smoke aerosol consisting primarily of soot and organic carbon. Continental pollution represents anthropogenic aerosols, including various species of sulfate and soot. Dirty pollution consists of the same aerosol types as continental pollution but at significantly higher levels.

The size of aerosol particles is an important factor in their classification and effects. Particle size influences particle properties, and the aerosol particle radius or diameter (dp) is a key property used to characterise aerosols. Aerosols with smaller particle diameters can penetrate deeper into the respiratory system, with potential hazards to human health. For example, aerosol particles with a diameter smaller than 10 μm can enter the bronchi, while particles smaller than 2.5 μm can reach the gas exchange region in the lungs.

Exploring the National Constitution Center: A Time-Bound Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Nucleation processes

Homogeneous nucleation is a critical mechanism, particularly in the context of atmospheric aerosols. It is responsible for the formation of a significant fraction of the total particles present in the atmosphere. This process occurs uniformly throughout the gaseous medium, resulting in the creation of new particles.

Binary nucleation of sulphuric acid and water, ternary nucleation involving sulphuric acid, water, and ammonia, and ion-induced nucleation are considered the most important nucleation processes in atmospheric aerosols. These processes have been observed across various regions of the atmosphere, including the boundary layer, the free troposphere, remote areas untouched by pollution, coastal regions, and boreal forests.

Heteromolecular and heterogeneous nucleation processes are also relevant in the atmosphere. Heterogeneous nucleation involves the presence of a foreign substance or surface that facilitates the nucleation process. This can include foreign particles or surfaces that act as catalysts, enhancing the rate of nucleation and influencing the growth of aerosol particles.

Furthermore, iodine oxides have been implicated in nucleation processes observed in certain coastal areas. The improvement in theoretical understanding and modelling capabilities has allowed for a kinetic treatment of nucleation processes. This approach, based on measured thermochemical data for cluster formation, is expected to surpass the classical nucleation theory.

Overall, a detailed comprehension of atmospheric aerosol nucleation processes is crucial as it directly impacts the number concentration and size distribution of atmospheric aerosols. These freshly formed particles influence cloud formation, precipitation, and climatic conditions. Anthropogenic emissions, such as those from industrial activities, can significantly alter atmospheric aerosol nucleation processes, underscoring the importance of understanding these mechanisms for environmental and climate-related studies.

Understanding Felony Larceny Thresholds in New York State

You may want to see also

Passive algorithms

The AERONET (AErosol RObotic NETwork) version 3 level 2.0 inversion product is a valuable tool for classifying aerosol types based on particle linear depolarization ratio (PLDR) and single-scattering albedo (SSA). This method allows for a more refined classification of mineral dust mixtures with other absorbing aerosols, such as pure dust (PD), dust-dominated mixed plumes (DDM), and pollutant-dominated mixed plumes (PDM). The AERONET instruments measure direct solar radiation and sky radiation, and their data is analysed using the AERONET inversion algorithm.

Machine learning spectral clustering algorithms have also been applied to aerosol classification. This approach uses variables such as AOD_Fine-mode, EAE, SSA, Absorption Angstrom Exponent (AAE), and Real Refractive Index (RRI) from global AERONET sites. The spectral clustering algorithm clusters scattered data points into multiple groups based on their uniqueness, creating more distinct clusters than conventional clustering algorithms. This method helps to understand the spatial distribution of aerosol optical properties and their correlation with land classification and aerosol climatology.

Additionally, the fine-mode fraction (FMF) from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (MODIS) and the aerosol index (AI) have been used to determine particle size and type. These passive algorithms provide valuable tools for classifying and understanding aerosol types, which is essential for studying atmospheric composition, pollution, and their impact on the environment and human health.

Amendments to the Constitution: A Historical Overview

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Aerosols are a suspension of fine solid particles or liquid droplets in the air or another gas. They can be generated from natural or human causes.

Key aerosol groups include sulfates, organic carbon, black carbon, nitrates, mineral dust, and sea salt. These often clump together to form a complex mixture.

Aerosols are classified according to their physical form and how they are generated. Some common types include dust, fume, mist, smoke, and fog.

Atmospheric aerosols are classified into six categories: biomass burning, rural, continental pollution, dirty pollution, desert dust, and polluted marine.

Particle size is a key property used to characterise aerosols. Monodisperse aerosols contain particles of uniform size, while polydisperse aerosols have varying particle sizes. Smaller particles can penetrate deeper into the respiratory system, potentially affecting the gas exchange region in the lungs.