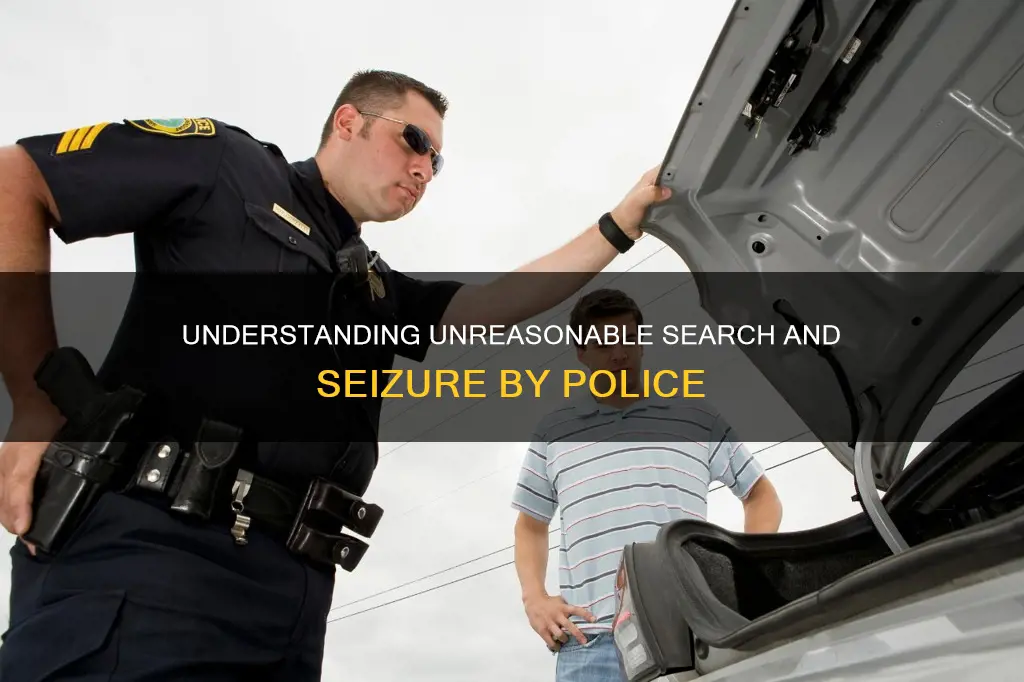

The Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution protects people from unreasonable searches and seizures by government officials. A search or seizure is generally considered unreasonable without a warrant, except in exigent circumstances. To obtain a warrant, a law enforcement officer must demonstrate probable cause to believe that a search or seizure is justified. The Fourth Amendment does not protect against all searches and seizures, but only those deemed unreasonable under the law. The Supreme Court has ruled that police officers can stop and frisk suspects without probable cause in public, but a stop and frisk becomes a search and seizure if the officer goes beyond a frisk of the suspect's outer clothing.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Search or seizure without a warrant | Unreasonable, unless there are exceptions |

| Search or seizure without probable cause | Unreasonable |

| Search or seizure extending beyond the authorized scope | Unreasonable |

| Search or seizure without valid consent | Unreasonable |

| Search or seizure without a legal right to own, occupy, or jointly control the property | Unreasonable |

| Search or seizure extending beyond the consent given | Unreasonable |

| Search or seizure without reasonable suspicion | Unreasonable |

| Search or seizure using excessive force | Unreasonable |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Searches without a warrant

A search or seizure without a warrant is generally considered unreasonable and is unconstitutional as it violates the Fourth Amendment. However, there are a few exceptions to this rule.

The Fourth Amendment outlines that people have the right to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, and that no warrants shall be issued without probable cause. This means that law enforcement officers must have probable cause to believe that a search or seizure is justified before obtaining a warrant.

In the case of State v. Helmbright, it was held that a warrantless search of a probationer's person or residence is not a violation of the Fourth Amendment if the officer has "reasonable grounds" to believe that the probationer has violated the terms of their probation. Similarly, in Arizona v. Gant, it was ruled that an officer may lawfully search any area of a vehicle if there is probable cause to believe that the vehicle contains evidence of criminal activity.

There are other instances where a warrant is not required for a search or seizure. For example, in exigent circumstances, if obtaining a warrant is impractical, an officer may be able to proceed without one. Additionally, in the case of California v. Acevedo, it was determined that a reasonable passenger would feel free to decline an officer's requests or terminate the encounter, and therefore not every encounter on a bus constitutes a seizure.

Another exception is when an individual consents to a warrantless search, such as when a suspect gives permission for their home or vehicle to be searched. In the case of Florida v. Jimeno, it was ruled that a criminal suspect's Fourth Amendment rights are not violated when they give consent for their car to be searched, and the police open a closed container that could reasonably hold the object of the search.

Furthermore, a stop-and-frisk is not considered a search and seizure, and therefore police officers can initiate this without probable cause in public. However, if they go beyond a frisk of the suspect's outer clothing, it becomes a search and seizure, and probable cause and a warrant may be required.

In summary, while searches and seizures without a warrant are typically deemed unreasonable, there are several exceptions to this rule, including exigent circumstances, consent, and specific types of encounters such as stop-and-frisk or routine stops and searches at international borders.

Boosting Your D&D 5e Constitution: Tips and Tricks

You may want to see also

Searches without probable cause

The Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution protects people from unreasonable searches and seizures by the government. An unreasonable search and seizure is one conducted without a legal search warrant, without probable cause, or extending the authorised scope of a search and seizure.

Probable cause is established when a "prudent man" who knew the facts and circumstances known to the officer would believe that a suspect committed a criminal offence. This is distinct from "reasonable suspicion", which falls short of probable cause. For example, "stop-and-frisk" searches are one of the exceptions to the warrant requirement, as are highway stops without any individualised suspicion.

In the absence of a warrant, a search or seizure may be deemed reasonable if there is probable cause and exigent circumstances, such as the need to prevent the destruction of evidence, protect officers or the public, or inhibit suspects from fleeing. For example, in State v. Helmbright, the Ohio court held that a warrantless search of a probationer's person or residence is not a violation of the Fourth Amendment if the officer has "reasonable grounds" to believe that the probationer has violated the terms of their probation.

However, a search or seizure without a warrant is generally considered unreasonable and may violate the Fourth Amendment. This is particularly true for searches inside a home, which are presumptively unreasonable without a warrant. In such cases, the court will balance the degree of intrusion on the individual's right to privacy against the need to promote government interests and special needs in exigent circumstances.

In summary, while there are exceptions, searches without probable cause are generally considered unreasonable and may violate the Fourth Amendment, particularly if they involve a significant intrusion into an individual's privacy without a valid warrant or exigent circumstances.

The Dominican Republic's Ever-Changing Constitution

You may want to see also

Searches extending beyond the scope

The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects individuals' reasonable expectation of privacy against government officers. It states that:

> [t]he right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

A search or seizure is generally considered unreasonable without a warrant, except in a few cases. The Fourth Amendment does not guarantee protection from all searches and seizures, but only those deemed unreasonable under the law.

- Search individuals not named in the warrant without additional justification.

- Search belongings not connected to the named suspect.

- Rely solely on proximity to criminal activity.

In the case of State v. Lambert, the police obtained a search warrant for an apartment and its resident, Randy, on suspicion of drug activity. When executing the warrant, the officers found three women in the apartment, none of whom were named in the warrant. The officers searched a purse on the table, which belonged to one of the women, Lambert, and found marijuana and amphetamines. Lambert filed a motion to suppress the evidence found in her purse, arguing that the search exceeded the scope of the warrant. The trial judge initially denied the motion but later reversed the decision and suppressed the evidence, finding that the officers had no legal basis to search Lambert's purse.

In addition, officers can exceed the scope of a search warrant by engaging in excessive or unnecessary destruction of property. For example, in United States v. Ramirez, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a search could become unreasonable if the destruction of property is excessive or unnecessary in relation to the execution of the warrant.

When the police exceed the scope of a warrant, any evidence obtained may be suppressed and cannot be used in court.

Oklahoma Constitution: A Surprisingly Wordy Document

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Searches with improperly obtained consent

Consent searches are a common form of warrantless search, where law enforcement agents obtain the voluntary consent of the person being investigated or a third party. The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects citizens from unreasonable search and seizure, requiring a search warrant or probable cause for a search to be performed. However, consent searches are an exception to the warrant requirement, and a search warrant or probable cause is not necessary if consent is given by someone with proper authority.

The prosecution must prove that consent was freely and voluntarily given, and courts will evaluate the totality of the circumstances to determine if consent was coerced. Consent may be revoked at almost any time during a search, either through statements, actions, or a combination of both. However, there are exceptions to revoking consent, such as during airport screenings and searches of prison visitors.

In the case of third-party consent, the consenting party must have common authority over the premises or a sufficient relationship to the effects being searched. The Supreme Court has held that a search is valid if the police reasonably believe the consenting party has authority, even if they are incorrect. However, if one co-occupant consents and another is present and expressly objects, the police cannot validly search the premises.

While officers are not required to inform individuals of their right to refuse consent, consent is not considered voluntary if the officer asserts their official status and the individual yields due to this factor. For example, if an officer erroneously states that they have a warrant, any consent given based on this statement does not constitute valid consent.

In summary, consent searches are an important exception to the warrant requirement of the Fourth Amendment, but they must be conducted with voluntary and informed consent from the individual being searched or a third party with proper authority. Courts will scrutinize the circumstances of consent to ensure it was not coerced, and individuals have the right to revoke their consent during a search.

Hammurabi's Code: Foundation of Constitutional Law

You may want to see also

Searches without reasonable suspicion

In the United States, the Fourth Amendment protects individuals' reasonable expectation of privacy against government officers. It states that:

> “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

Reasonable suspicion is a legal standard of proof that is more than an "inchoate and unparticularized suspicion or 'hunch'". It must be based on "specific and articulable facts", "taken together with rational inferences from those facts", and the suspicion must be associated with a specific individual. If an officer has a reasonable suspicion, they may frisk or briefly detain a suspect. However, reasonable suspicion does not provide grounds for arrest or a search warrant.

In the case of State v. Helmbright, the Ohio court held that a warrantless search of a probationer's person or place of residence is not a violation of the Fourth Amendment if the officer who conducts the search possesses “reasonable grounds” to believe that the probationer has failed to comply with the terms of their probation.

In addition, the Fourth Amendment does not apply to searches at the border or customs, which can be conducted without reasonable suspicion.

The Constitution's Home Rule: Preserving State Powers

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

An unreasonable search and seizure is a search and seizure executed without a legal search warrant or probable cause, or extending the authorized scope of the search and seizure.

The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects people from unreasonable searches and seizures by the government. It states that "the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized."

A seizure of a person occurs when the police's conduct communicates to a reasonable person that they are not free to ignore the police presence and leave. There must be a show of authority by the police officer, and the person being seized must submit to this authority.

Courts have ruled that the police can conduct warrantless searches under certain conditions, such as when items are in plain view, or when they get consent from a person with a reasonable expectation of privacy, such as a spouse.