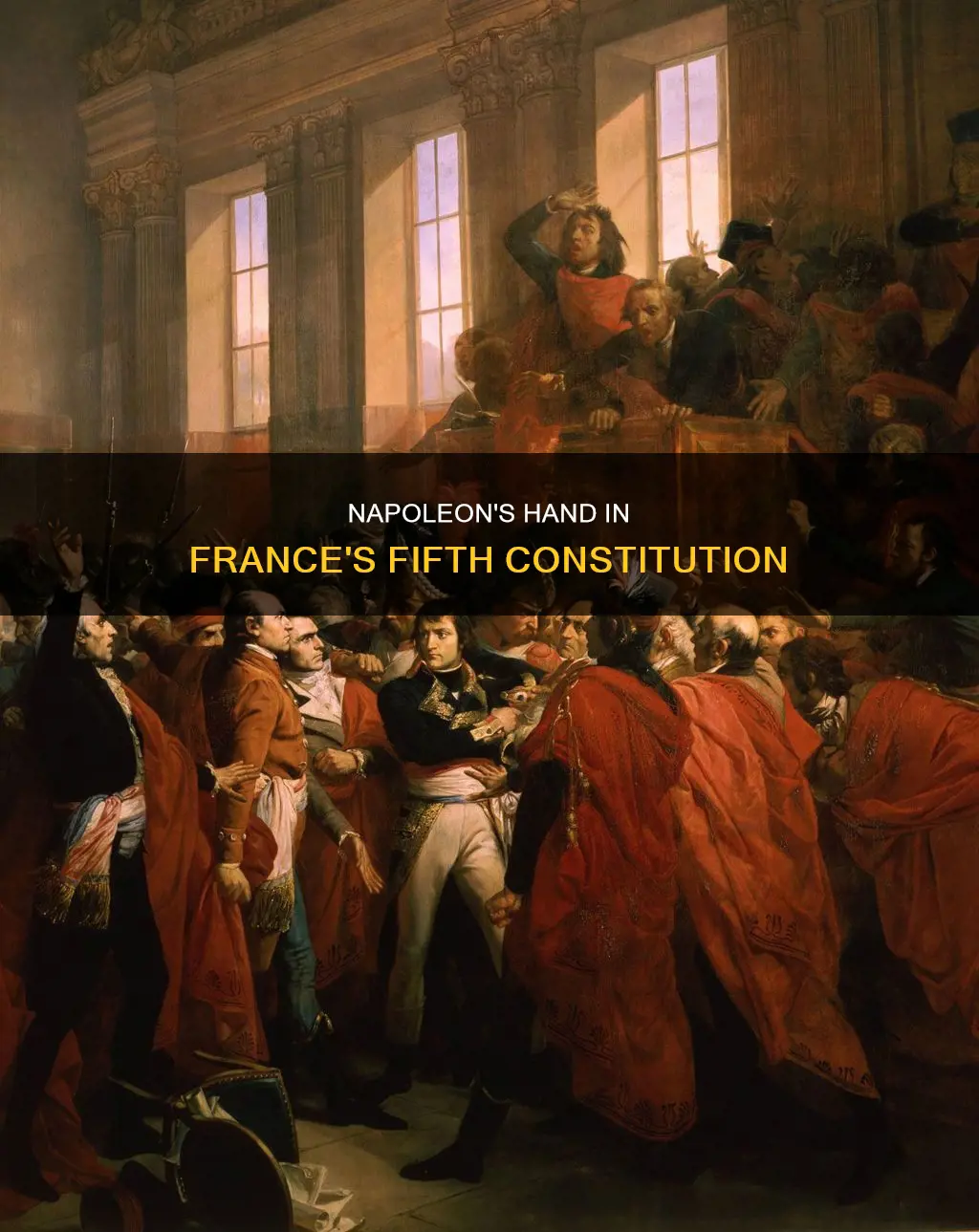

On February 7, 1800, a referendum confirmed a new constitution in France, vesting power in the hands of the First Consul, Napoleon Bonaparte. This was the Constitution of the Year XII, which was later amended by the Additional Act (1815) after Napoleon's return from exile. Napoleon established a liberal, authoritarian, and centralized republican government, with the First Consul holding extensive powers. While some historians have argued that the Napoleonic institutions never truly existed or were artificial, others have described the rules by which the Napoleonic government worked, focusing on its absolutism or Caesarism. The Constitution of the Year XII was preceded by a bloodless coup d'état led by Napoleon, which overthrew the Directory and replaced it with the French Consulate. Later, on December 2, 1851, Napoleon launched another coup d'état to retain power, which led to the Constitution of January 14, 1852, establishing the Second Empire.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Napoleon's Constitution of the Year XII

The Constitution of the Year XII, also known as Napoleon's Constitution, was a significant document in the history of France. It was promulgated during a period of transition in France, from the fall of the Directory in the Coup of 18 Brumaire (1799) to the start of the Napoleonic Empire in 1804. This constitution established Napoleon Bonaparte as the head of a more liberal, authoritarian, and centralized republican government, although he did not declare himself the head of state.

The Constitution of the Year XII was notable for vesting significant power in the hands of the First Consul, Napoleon himself. It left only a nominal role for the other two consuls, with over 99% of voters approving this shift in a referendum. This constitution was later amended by the Additional Act (1815) after Napoleon's return from exile, virtually replacing the previous Napoleonic Constitutions.

The document known as the Charter of 1815, signed on April 22, 1815, was also a significant element of Napoleon's constitutional legacy. This French constitution was prepared by Benjamin Constant at the request of Napoleon I. While it affirmed a rejection of constitutional monarchies, the articles that followed described a quasi-monarchist head of state, granting him extensive powers.

The Constitution of the Year XII had a complex structure, with a legislative body and a Senate. The legislative body could denounce ministers or councillors of state if they gave orders contrary to the constitutions and laws of the Empire. The Senate, meanwhile, was responsible for hearing the orators of the Council of State and making decrees or resolutions.

In recent times, historians have debated the significance and validity of Napoleon's constitutions. Some argue that they were merely window-dressing for the pursuit of personal power, while others describe them as "absolutist" or "Caesarist". Despite these criticisms, the constitutional codes of the Napoleonic era continue to be studied and interpreted, offering insights into the complex political landscape of the time.

The Mexican Constitution: Revolution's Child?

You may want to see also

The French Consulate

On November 9, 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte led a bloodless coup d'état that overthrew the Directory and replaced it with the French Consulate. This event, which took place on 18 Brumaire, Year VIII of the French Republican Calendar, marked Napoleon's rise to power as the First Consul of a more liberal, authoritarian, autocratic, and centralized republican government in France. Notably, Napoleon did not declare himself the head of state at this time.

The Constitution of the Year VIII served as a compromise between the aspirations of Sieyès and the Brumairians in the Assembly and Bonaparte's own views. It represented a shift towards a more authoritarian form of governance, with the First Consul wielding significant power. The independence of the legislative power was diminished, as the President was responsible for initiating legislative acts that deputies could not amend. Additionally, the President had the exclusive right to appoint all functions and choose ministers, whose actions could not be controlled by the deputies.

The Constitution: Liberty and Justice for All?

You may want to see also

Napoleon's popularity and accomplishments

Napoleon Bonaparte, also known as Napoleon I, was a French military general, first consul, and emperor of the French. He played a key role in the French Revolution (1789–99) and is considered one of the greatest military generals in history. His popularity was due in part to his reputation as a charismatic and ambitious leader. He is also known for his reforms and conquests, which expanded French dominion.

Napoleon's accomplishments were numerous and significant. He revolutionized military organization and training, modernizing the French military and initiating the Napoleonic Wars (c. 1801–15). He also sponsored the Napoleonic Code, a prototype of later civil-law codes that streamlined the French legal system. In addition, he reformed the French educational system and supported the arts. He negotiated the Concordat of 1801 with the papacy, improving relations between France and the pope.

Napoleon's military genius was demonstrated in his Italian campaign, where he bewildered his enemies with rapid movements and advanced into Austria, eventually concluding the Treaty of Campo Formio, which gave France more territory. He led an army of about 600,000 into Russia in 1812, winning the Battle of Borodino, and defeated Austria and Russia at Austerlitz in 1805. He also crushed the Prussians at Jena and Auerstädt in 1806 and defeated the Russians at Friedland in 1807. These triumphs brought most of Europe to its knees and marked the beginning of Napoleon's empire.

However, some historians argue that the Napoleonic institutions and constitutional codes were "artificial" and merely window-dressing for the pursuit of personal power. Nonetheless, Napoleon's reforms left a lasting mark on the institutions of France and much of Western Europe.

Roe v. Wade: Constitutional Rights and Wrongs

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The quasi-monarchist conception of the head of state

The Constitution of the Year XII, also known as Napoleon's Constitution, was a bloodless coup d'état that overthrew the Directory and replaced it with the French Consulate. This was the first constitution since the Revolution that did not include a Declaration of Rights. On February 7, 1800, a public referendum confirmed the new constitution, with power vested in the hands of the First Consul, later identified as Napoleon Bonaparte.

Napoleon established himself as the head of a more liberal, authoritarian, autocratic, and centralized republican government in France, despite not declaring himself the official head of state. The Constitution of the Year XII was later amended by the Additional Act (1815) after Napoleon returned from exile, virtually replacing the previous Napoleonic Constitutions.

The Constitution of 14 January 1852, promulgated by President Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, replaced the Constitution of 4 November 1848 as the founding text of the Second Republic. This constitution affirmed the rejection of constitutional monarchies, yet the articles that followed described a quasi-monarchist conception of the head of state. The President of the Republic was granted extensive powers, including the right to declare war, sign treaties, appoint functions, and choose ministers.

The independence of the legislative power was diminished, and the President was responsible for initiating legislative acts that deputies could not amend. The parliament was composed of a legislative body with 250 deputies elected every six years and a Senate, including ex officio members like marshals, admirals, and cardinals. The President could also appoint members for life to the Senate to resolve issues not addressed in the Constitution. Overall, the Constitution of 14 January 1852, with its quasi-monarchist characteristics, marked a significant shift in the French political system.

The Constitution and Trial by Jury

You may want to see also

The constitutional codes as artificial

The constitutional codes of the Consulate and Empire have been described as "rather artificial". This characterisation is supported by several observations about the nature and function of Napoleon's regime. Firstly, historians have argued that the constitutions of the Napoleonic era were merely a facade, serving as a means to personal power rather than reflecting a genuine commitment to constitutionalism. This perspective highlights the discrepancy between the purported rules and the reality of Napoleonic governance, suggesting that the constitutional codes were not an accurate representation of the power dynamics within the regime.

Secondly, the Constitution of the Year XII, promulgated during Napoleon's reign, was later extensively amended by the Additional Act (1815) after his return from exile. This modification significantly altered the previous Napoleonic Constitutions, further indicating the fluid and adaptable nature of the constitutional codes during this period.

Moreover, Napoleon Bonaparte, as First Consul, established a highly centralised republican government in France. While he did not declare himself head of state, he consolidated power by vesting all real authority in the position of First Consul, relegating the other two consuls to nominal roles. This concentration of power in a single position contradicts the principles of a true constitutional regime, where power is typically distributed among various branches or entities to ensure checks and balances.

In addition, the independence of the legislative power during Napoleon's regime was diminished. The President, who was granted extensive powers, was responsible for initiating legislative acts that deputies could not amend. This lack of legislative autonomy further reinforces the notion that the constitutional codes were artificial constructs that did not genuinely constrain or shape the exercise of power within the Napoleonic regime.

Furthermore, the Constitution of the Year XII, as exemplified in certain proclamations, emphasised the role of the Senate and the Legislative Body. However, the ability of these bodies to exert meaningful influence or serve as a check on executive power is questionable. The Senate's role was limited to hearing oracles of the Council of State, while the Legislative Body could denounce ministers or councillors who acted contrary to the constitutions and laws of the Empire. These provisions suggest a certain degree of formality and structure, but they do not necessarily indicate a robust constitutional framework that could effectively balance the powers of the executive and legislative branches.

Overall, the description of the constitutional codes as "rather artificial" reflects the complex and often contradictory nature of the Napoleonic regime. While there were attempts to establish constitutional principles and frameworks, the concentration of power in Napoleon's hands, the limited independence of the legislative branch, and the adaptable nature of the constitutions suggest that the constitutional codes were not deeply entrenched or fully realised during this period.

IRS Legality: Examining Constitutional Roots

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Napoleon was not responsible for the fifth constitution in France. The fifth constitution in France was established on October 4, 1958. Napoleon Bonaparte was, however, responsible for the first constitution in France, which was established on December 24, 1799.

The first constitution in France was known as the Consulate. It was established on December 24, 1799, during the Year VIII of the French Revolutionary Calendar.

The first constitution gave Napoleon most of the powers of a dictator. He established himself as the head of a centralized republican government in France without declaring himself the head of state.

Yes, the first constitution was amended twice, and in each case, the amendments strengthened Napoleon's power. The first amendment was made in 1802, making Napoleon the First Consul for Life. The second amendment was the Constitution of the Year XII, established in 1804, which made Napoleon I, Emperor of the French.

Yes, Napoleon established the Constitution of the Year XII, which was later amended by the Additional Act (1815) after he returned from exile. He also established the Charter of 1815, which was signed on April 22, 1815, and served as the French constitution after his return from exile.

![The political and historical works of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte now first collected. With an original memoir of his life, brought down to the promulgation of the constitution of 1852. V [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81nNKsF6dYL._AC_UY218_.jpg)