The United States Constitution, primarily the First Amendment, has been violated numerous times over the past two centuries. While individuals cannot violate the Constitution, the government can infringe upon citizens' rights, such as free speech, freedom of religion, and freedom of the press. The First Amendment also applies to the states through the 14th Amendment. Throughout history, several presidents have been accused of violating the Constitution, including Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Donald Trump. Lincoln's actions during the Civil War, such as suspending habeas corpus, were controversial, but some argue they were permissible under the Constitution. Trump has been criticized for violating the rule of law and acting unilaterally, such as in his attempt to end birthright citizenship. While the Constitution is meant to protect the rights of Americans, it is not always upheld, and those who violate it are rarely held accountable.

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

$9.99 $9.99

What You'll Learn

Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus

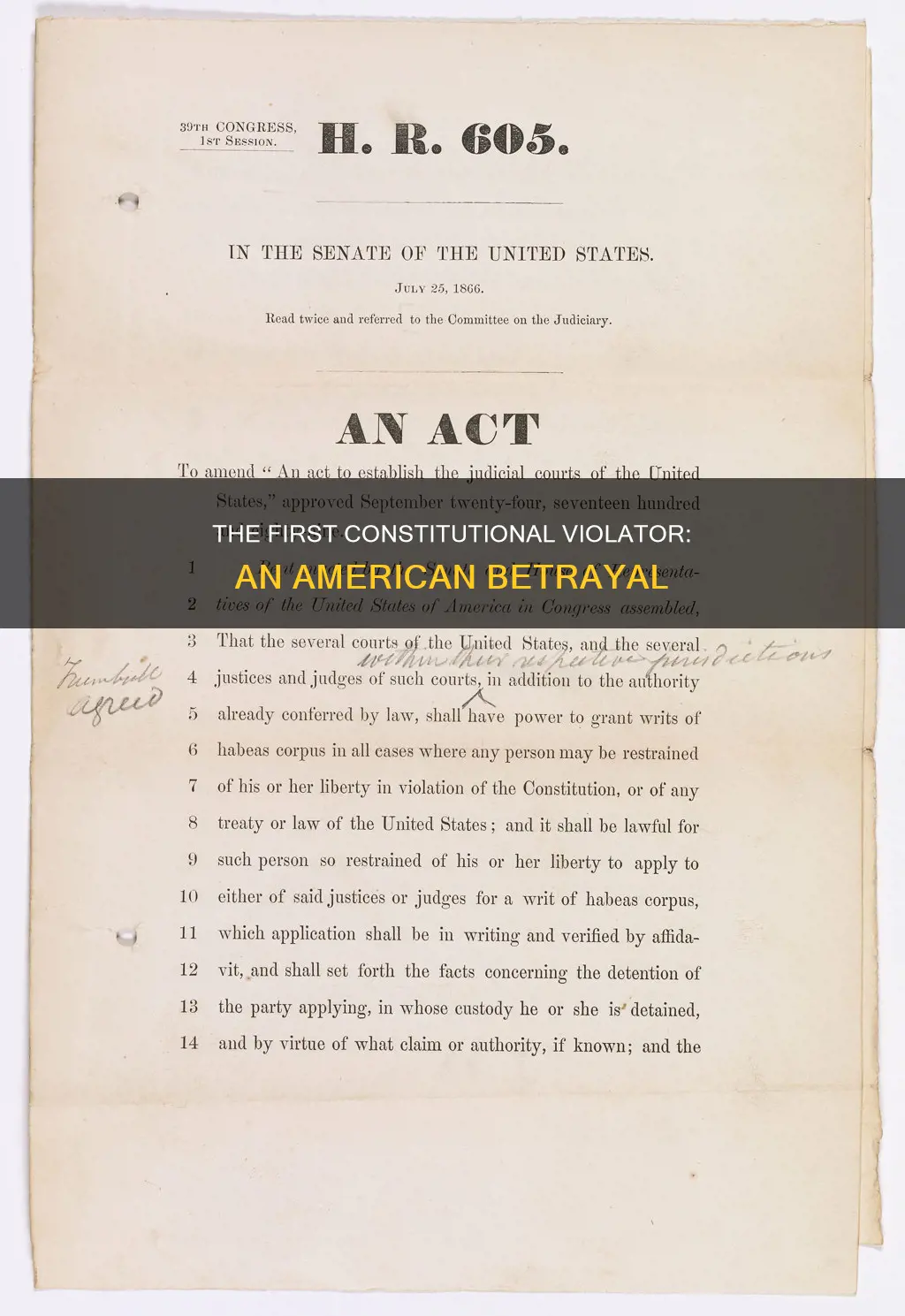

While it is challenging to determine the very first instance of violation of the Constitution, one of the most notable instances is Abraham Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus during the Civil War.

The writ of habeas corpus is a legal action or right preventing the government from unlawfully imprisoning individuals outside of the judicial process. It is the right of any person under arrest to appear in person before a court to ensure they have not been falsely accused. The US Constitution specifically protects this right in Article I, Section 9, which states: "The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it."

In April 1861, at the outbreak of the American Civil War, Washington, D.C., was largely undefended, and rioters in Baltimore, Maryland, threatened to disrupt the reinforcement of the capital by rail. Due to these circumstances, President Lincoln authorized his military commanders to suspend the writ of habeas corpus between Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia, later extending it to New York City. Lincoln's initial suspension of habeas corpus aimed to try large numbers of civilian rioters in military courts and prevent the movement of Confederate troops towards Washington.

In June 1861, U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney, ruling in Ex Parte Merryman, stated that the authority to suspend habeas corpus lay exclusively with Congress, and thus, Lincoln's suspension was invalid. Lincoln, however, refused to abide by the ruling. In February 1862, Lincoln ordered the release of all political prisoners, offering them amnesty for past treason or disloyalty as long as they did not aid the Confederacy.

In September 1862, faced with opposition to his calling up of the militia, Lincoln again suspended habeas corpus, this time throughout the entire country. This decision was one of his most controversial, subjecting protestors to martial law and making anyone charged with interfering with the draft, discouraging enlistments, or aiding the Confederacy liable to trial and punishment by military commissions.

The suspension of habeas corpus by Lincoln sparked debates about the constitutionality of his actions, with critics arguing that he had subverted the Constitution. Lincoln defended his actions, arguing that acts that might be illegal in peacetime might be necessary "in cases of rebellion" when the nation's survival was at stake. This event highlights the complexities that can arise when balancing civil liberties with national security during times of crisis.

The First Draft of the Constitution: When Did It Begin?

You may want to see also

Trump's executive order to end birthright citizenship

While there is no clear answer to who first violated the constitution, one source mentions Abraham Lincoln as a possibility. Lincoln's actions during the Civil War, such as suspending habeas corpus and taking certain actions without Congressional authorization, have been seen by some as unconstitutional. However, law professor Daniel Farber argues that most of Lincoln's actions were permissible under the Constitution and that any infringements were not egregious.

Now, regarding Trump's executive order to end birthright citizenship, the former president sought to redefine the birthright citizenship clause of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The 14th Amendment, adopted in 1868 after the Civil War, states that "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside." Trump's executive order aimed to deny automatic citizenship to children born in the United States if their parents were in the country illegally or temporarily.

The Trump administration asked the Supreme Court to allow the restrictions on birthright citizenship to take effect while legal battles were ongoing. Acting Solicitor General Sarah Harris argued that Trump's order was constitutional, claiming that the 14th Amendment's citizenship clause does not extend citizenship to everyone born in the United States. However, this interpretation has been widely contested, and legal experts believe Trump's attempt to usurp the Constitution will likely fail.

Trump's order faced significant opposition, with three federal appeals courts and several district courts blocking it. Senior U.S. District Judge John Coughenour of the Western District of Washington called the order "blatantly unconstitutional." The order was also challenged by roughly two dozen states, as well as individuals and groups, who argued that it violated the Constitution. The challengers argued that birthright citizenship is a fundamental constitutional right and that the administration had not demonstrated an urgent need for the order.

The fate of Trump's executive order remains uncertain, and the Supreme Court's decision could set a significant precedent regarding the power of the executive branch and the interpretation of the 14th Amendment.

The First Constitution: Founding Principles of a Nation

You may want to see also

Free speech and press

Free speech and freedom of the press are enshrined in the First Amendment of the US Constitution, which states that "Congress shall make no law [...] abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press".

The First Amendment was drafted by James Madison and introduced to the House of Representatives on June 8, 1789. Madison's draft provided:

> The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable.

Madison's draft was influenced by the theories of his Jeffersonian compatriots. In 1788, Thomas Jefferson wrote to Madison, suggesting that the free speech-free press clause might read:

> The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write or otherwise to publish anything but false facts affecting injuriously the life, liberty, property, or reputation of others or affecting the peace of the confederacy with foreign nations.

The First Amendment's protection of free speech and press has been interpreted and refined over the years by the US Supreme Court. For example, in 1919, the Court upheld convictions for violating the Espionage Act by attempting to cause insubordination in the military service through the circulation of leaflets, suggesting First Amendment restraints on subsequent punishment as well as on prior restraint. In 1942, the Court first identified the "fighting-words" exception to the First Amendment, which states that free speech does not protect speech that incites people to break the law, including committing acts of violence. In Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), the Supreme Court held that inciting a crowd to violence was not protected speech.

The First Amendment's protection of free speech and press has also been invoked in cases involving public universities, such as Iowa State, which are subject to the constitutional restrictions set forth in the First Amendment. However, universities may restrict speech that falsely defames a specific individual, constitutes a genuine threat or harassment, or is intended and likely to provoke imminent unlawful action.

The Constitution's Opening: Democracy's Foundation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$47.19 $58.99

State sovereignty

The concept of state sovereignty in the United States has evolved over time, with the Constitution and relevant case law defining the lines of authority between states and the federal government. The Fourteenth Amendment marked a significant shift in power, subjecting state legislation to oversight by the federal judiciary or Congress to ensure compliance with due process and equal protection.

Historically, there have been four periods of widespread Constitutional criticism, characterised by the idea of states' rights – that specific political powers are reserved for state governments rather than the federal government. This doctrine reflects the Whig philosophy accepted among the original thirteen colonies in 1776, which asserted that Congress should be equal to any state legislature, and only the people within each state are sovereign.

The First and Second Continental Congresses in 1774 and 1775, respectively, further shaped the concept of state sovereignty. The First Continental Congress stopped short of advocating for independence or a separate government for the states, instead imposing an economic boycott on British trade. The Second Continental Congress, on the other hand, functioned as a de facto national government during the Revolutionary War, centralising power and creating a cohesive league of states.

The Constitution also addresses tribal sovereignty, recognising the distinct limited sovereignty of Native American tribes. The Supreme Court has affirmed tribal authority to impose taxes on their members and non-members on reservations, acknowledging their "general governmental jurisdiction". However, questions of state taxation involving transactions between tribes and non-members on reservations are more complex, requiring a balancing of state, federal, and tribal interests.

Additionally, Congress can use the Spending Clause to mandate certain state actions as a prerequisite for receiving federal funds. However, these conditions must be proportional and non-coercive, and they must relate to the underlying grant. If these conditions are not met, particularly if they infringe on state sovereignty or impose undue financial burdens, they may violate federalism principles.

Signs of a First Date: Defining Moments and More

You may want to see also

Secession

In the context of the United States, secession refers to the voluntary withdrawal of one or more states from the Union. The idea of secession has been a feature of American politics almost since the country's birth.

During the founding era, many public figures, including Founding Father Gouverneur Morris, a primary author of the Constitution, claimed that "secession, under certain circumstances, was entirely constitutional." Morris, a Federalist and a Hamilton ally, felt threatened by the rise of Thomas Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party and viewed Jefferson's unilateral purchase of the Louisiana territory as violating foundational agreements between the original 13 states.

James Madison, often referred to as "The Father of the Constitution," strongly opposed the argument that secession was permitted by the Constitution. In a letter to Daniel Webster, Madison wrote:

> "I return my thanks for the copy of your late very powerful Speech in the Senate of the United S. It crushes 'nullification' and must hasten the abandonment of 'Secession'. But this dodges the blow by confounding the claim to secede at will, with the right of seceding from intolerable oppression. The former answers itself, being a violation, without cause, of a faith solemnly pledged. The latter is another name only for revolution, about which there is no theoretic controversy. Thus, I affirm an extraconstitutional right to revolt against conditions of 'intolerable oppression'; but if the case cannot be made (that such conditions exist), then I reject secession—as a violation."

The debate over the legality of secession came to a head during the Civil War. In his book "Lincoln's Constitution," law professor Daniel Farber argues that the Southern States did not have the right to secede, but he also contends that the case for secession was not frivolous. Farber concludes that Lincoln's actions during the war, such as "calling up the militia, deploying the military, and imposing a blockade," were permissible under the Constitution or subsequently authorized by Congress. However, he acknowledges that some of Lincoln's actions, such as suspending habeas corpus and suppressing free speech, infringed upon the Constitution.

In the end, the Supreme Court ruled in Texas v. White (1869) that unilateral secession was unconstitutional, while commenting that revolution or consent of the states could lead to a successful secession.

Citing the US Constitution's First Amendment in MLA Style

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

While there is no clear answer to this question, the Trump administration has been accused of violating the Constitution through executive orders, such as the one purporting to end birthright citizenship, which a federal judge deemed "blatantly unconstitutional."

Trump violated the Constitution by issuing an executive order that attempted to end birthright citizenship, firing fraud-finding inspectors general without providing a rationale to Congress, and pardoning the January 6 insurrectionists.

Yes, Richard Nixon abused his power by refusing to spend funds allocated by Congress without providing a valid reason, which led to the passing of the Impoundment Control Act of 1974 to curb this practice.

Presidents can violate the Constitution by defying court orders, refusing to spend funds allocated by Congress, or taking actions that interfere with the free exercise of religion.