The concept of the political spectrum, a framework used to categorize political positions along a continuum, is often traced back to the French Revolution. During this tumultuous period, the National Assembly’s seating arrangement became symbolic: radicals sat on the left, moderates in the center, and conservatives on the right. This spatial division reflected differing views on monarchy, religion, and social reform, laying the groundwork for the left-right political spectrum. While no single individual invented the political spectrum, its origins are deeply rooted in the ideological clashes of late 18th-century France, evolving over time into a universal tool for understanding political ideologies.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Early Political Thought: Ancient Greek philosophers like Plato and Aristotle laid groundwork for political ideologies

- French Revolution Influence: Left-right spectrum emerged during French Revolution based on seating arrangements

- Jean-Pierre Brissot’s Role: Brissot first used left and right to describe political factions in 1791

- Modern Spectrum Evolution: Expanded to include authoritarian-libertarian axis, creating a 2D model

- Criticism of Spectrum: Critics argue it oversimplifies complex political beliefs and ideologies

Early Political Thought: Ancient Greek philosophers like Plato and Aristotle laid groundwork for political ideologies

The concept of a political spectrum, while not explicitly defined in ancient times, finds its intellectual roots in the works of early Greek philosophers, particularly Plato and Aristotle. These thinkers laid the groundwork for understanding political ideologies by examining the nature of governance, justice, and the ideal state. Their ideas, though not systematized into a left-right spectrum, introduced fundamental distinctions that would later shape political thought. Plato, in his seminal work *The Republic*, explored the ideal form of government, advocating for a philosopher-king—a ruler guided by wisdom and reason. This vision contrasted with existing systems like democracy, which Plato criticized for its susceptibility to demagoguery and chaos. By categorizing governments into types such as timocracy, oligarchy, democracy, and tyranny, Plato implicitly introduced a framework for evaluating political systems based on their virtues and flaws.

Aristotle, Plato's student, expanded on these ideas in his work *Politics*, providing a more empirical analysis of governance. He classified governments into three "correct" forms—monarchy, aristocracy, and polity—and their "deviant" counterparts—tyranny, oligarchy, and democracy. Aristotle's distinction between rule for the common good versus rule for personal gain marked an early attempt to evaluate political systems morally and structurally. Unlike Plato, Aristotle was more pragmatic, acknowledging the viability of different systems depending on societal context. His emphasis on the middle ground, particularly in the polity, where power is shared among the many, foreshadowed later concepts of balanced governance and moderation in political ideology.

Both philosophers introduced key themes that would resonate in political thought for centuries. Plato's focus on justice, as outlined in *The Republic*, centered on the harmonious functioning of the state, with each class fulfilling its role. This hierarchical vision contrasted with Aristotle's more pluralistic approach, which recognized the legitimacy of diverse political arrangements. Their debates on the role of the individual, the state, and the nature of justice created a dialectic that would influence later thinkers, from medieval scholars to Enlightenment philosophers. While neither Plato nor Aristotle explicitly devised a political spectrum, their analyses of government types and their critiques of existing systems provided the intellectual tools to categorize and compare political ideologies.

The Greek philosophers' emphasis on reason, ethics, and the common good also set a standard for evaluating political systems. Plato's utopian vision of a state governed by philosophers highlighted the importance of knowledge and virtue in leadership, a theme that would recur in discussions of meritocracy and technocracy. Aristotle's focus on practical governance and the importance of constitutional design underscored the need for stability and fairness in political institutions. Their works encouraged later thinkers to systematically analyze the strengths and weaknesses of different forms of government, paving the way for the development of more structured political taxonomies.

In summary, while the modern political spectrum emerged much later, the intellectual foundations were firmly established by ancient Greek philosophers. Plato and Aristotle's explorations of governance, justice, and the ideal state introduced enduring distinctions between types of rule and criteria for evaluating them. Their ideas not only shaped the Western political tradition but also provided the conceptual framework necessary for later thinkers to systematize political ideologies into the spectra we recognize today. Their contributions remain essential to understanding the origins of political thought and its evolution over millennia.

Ivanka Trump's Political Rise: Power, Influence, and Family Legacy Explored

You may want to see also

French Revolution Influence: Left-right spectrum emerged during French Revolution based on seating arrangements

The concept of the left-right political spectrum, a foundational framework for understanding political ideologies, owes its origins to the tumultuous period of the French Revolution. This revolutionary era not only reshaped France but also introduced a spatial metaphor that continues to dominate political discourse globally. The emergence of the left-right spectrum is directly tied to the seating arrangements in the National Assembly during the early years of the Revolution, a seemingly mundane detail that carried profound implications for political organization and ideology.

During the French Revolution, the National Assembly became the epicenter of political debate and decision-making. Deputies representing various factions gathered to deliberate on the future of France. The seating arrangement in the Assembly was not arbitrary; it reflected the ideological divisions among the representatives. Those who supported radical changes, including the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic, tended to sit on the left side of the Assembly. This group, which included figures like Maximilien Robespierre and Georges Danton, advocated for egalitarian principles, popular sovereignty, and a break from the old order. Their position on the left thus became synonymous with progressive, revolutionary, and later, socialist and liberal ideals.

In contrast, deputies who favored more moderate reforms or sought to preserve elements of the traditional order, such as the monarchy or the influence of the clergy, sat on the right side of the Assembly. This group, which included conservatives and constitutional monarchists, emphasized stability, hierarchy, and the preservation of existing institutions. Their position on the right became associated with conservative, traditionalist, and reactionary ideologies. The physical division in the Assembly mirrored the ideological chasm between these two camps, and the terms "left" and "right" quickly became shorthand for these opposing political perspectives.

The seating arrangement in the National Assembly was more than just a logistical detail; it became a powerful symbol of political identity and alignment. As the Revolution progressed, the left-right distinction gained wider recognition and was adopted beyond the confines of the Assembly. It provided a simple yet effective way to categorize and understand the complex array of political beliefs and movements emerging during this period. The spatial metaphor of left and right allowed people to position themselves and others along a continuum, from radical change to conservative preservation.

The influence of the French Revolution on the left-right spectrum extended far beyond France's borders. As ideas and news of the Revolution spread across Europe and the world, so too did the conceptual framework of the political spectrum. The left-right divide became a universal tool for analyzing and comparing political ideologies, shaping the way people understood and engaged with politics. Even today, the terms "left-wing" and "right-wing" remain central to political discourse, a testament to the enduring legacy of the French Revolution's seating arrangements in the National Assembly. This historical moment not only transformed France but also provided the world with a lasting framework for navigating the complexities of political thought.

Are Political Parties 501(c)(3) Organizations? Unraveling Tax Exemptions

You may want to see also

Jean-Pierre Brissot’s Role: Brissot first used left and right to describe political factions in 1791

Jean-Pierre Brissot, a prominent French revolutionary and politician, played a pivotal role in the development of the political spectrum as we understand it today. In 1791, during the early stages of the French Revolution, Brissot introduced the terms "left" and "right" to describe the seating arrangements and ideological divisions within the National Assembly. This innovation marked the first recorded use of these terms in a political context, laying the groundwork for the modern political spectrum. Brissot's contribution was not merely terminological but reflected the deepening ideological rifts within the revolutionary movement, as factions began to coalesce around distinct principles and goals.

Brissot himself was a leading figure of the Girondist faction, which sat to the "left" of the more conservative monarchists in the Assembly. The left, as defined by Brissot, represented those who advocated for radical republicanism, greater democratic reforms, and a more assertive foreign policy. In contrast, the right comprised those who favored preserving elements of the monarchy, maintaining social hierarchies, and pursuing a more cautious approach to revolution. By using spatial metaphors—left and right—Brissot provided a simple yet powerful framework for understanding complex political differences, a framework that would endure and evolve over centuries.

The context in which Brissot introduced these terms was fraught with tension and ideological conflict. The French Revolution was a period of rapid political transformation, with various factions vying for influence and control. Brissot's use of "left" and "right" was not just descriptive but also strategic, as it helped to clarify alliances and opposition within the Assembly. His innovation allowed politicians, intellectuals, and the public to conceptualize political disagreements along a single axis, making it easier to navigate the chaotic landscape of revolutionary politics. This spatial representation of ideology became a cornerstone of political discourse, transcending its French origins to become a universal tool for political analysis.

Brissot's role in inventing the political spectrum is particularly significant because it reflected the revolutionary era's emphasis on categorization and systematization. The Enlightenment, which heavily influenced the Revolution, prized reason and order, and Brissot's use of left and right aligned with this intellectual trend. By creating a binary framework, he provided a means to simplify and structure the complex web of ideas and interests that characterized the period. This simplification did not diminish the richness of political thought but rather made it more accessible, enabling broader participation in political debates.

While Brissot's use of "left" and "right" was specific to the context of the French Revolution, its impact was far-reaching. The terms quickly gained traction and were adapted to describe political divisions in other countries and eras. Over time, the spectrum expanded to include additional dimensions, such as authoritarianism vs. libertarianism, but the foundational left-right axis remains central to political discourse. Brissot's contribution, therefore, was not just a product of his time but a lasting legacy that continues to shape how we understand and engage with politics. His role in inventing the political spectrum underscores the enduring power of language and metaphor in organizing human thought and action.

Exploring Power, Society, and Humanity: The Compelling Reasons to Read Political Novels

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$32.99 $32.99

$43.7 $67.5

Modern Spectrum Evolution: Expanded to include authoritarian-libertarian axis, creating a 2D model

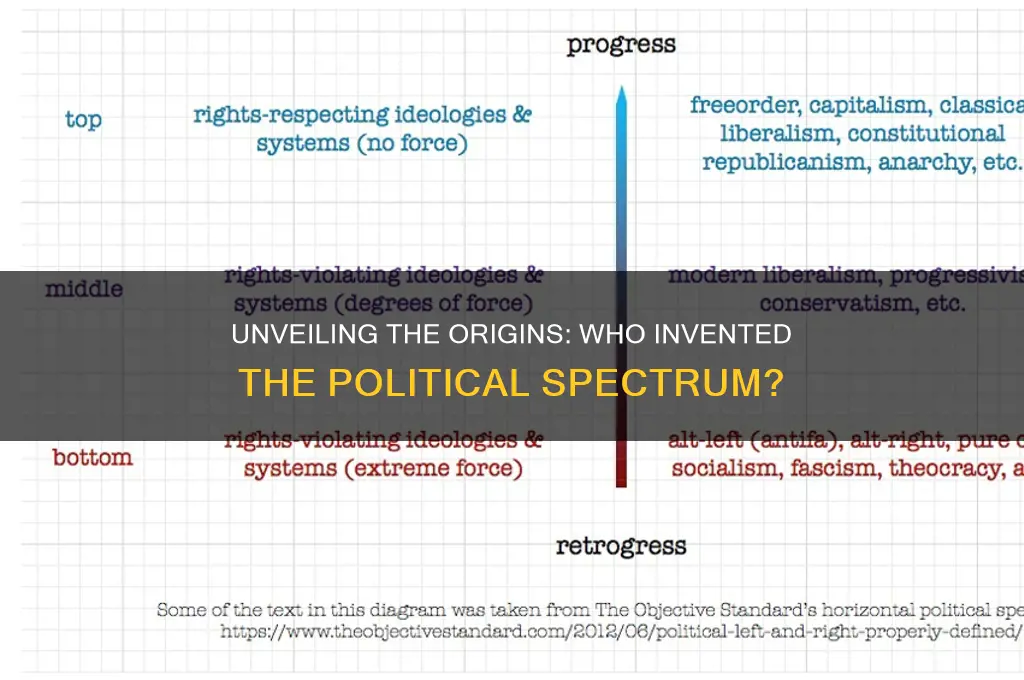

The traditional one-dimensional political spectrum, often depicted as a simple left-right line, has undergone significant evolution to better capture the complexity of political ideologies. One of the most notable advancements in this evolution is the introduction of the authoritarian-libertarian axis, transforming the spectrum into a two-dimensional model. This expansion allows for a more nuanced understanding of political beliefs by distinguishing between economic and social dimensions. While the left-right axis typically represents economic views, with the left advocating for collective ownership and redistribution, and the right favoring individual ownership and free markets, the authoritarian-libertarian axis addresses social and personal freedoms. This modern spectrum evolution provides a more comprehensive framework for analyzing political ideologies.

The inclusion of the authoritarian-libertarian axis is often attributed to political scientists and thinkers who sought to address the limitations of the one-dimensional model. Although no single individual can be credited with its invention, the concept gained prominence in the late 20th century as scholars recognized the need to differentiate between economic policies and social control. Authoritarianism, characterized by strong central authority and limited personal freedoms, contrasts with libertarianism, which emphasizes individual liberty and minimal government intervention in personal affairs. This axis allows for the classification of ideologies that might otherwise appear contradictory on a one-dimensional spectrum, such as authoritarian socialism or libertarian capitalism.

The two-dimensional model has become particularly useful in contemporary political analysis, as it accommodates a wider range of ideologies and movements. For instance, it can distinguish between left-wing authoritarians, such as certain communist regimes, and left-wing libertarians, like anarcho-communists. Similarly, it differentiates between right-wing authoritarians, such as fascists, and right-wing libertarians, like classical liberals. This expanded spectrum also highlights the diversity within political parties and movements, which often contain factions with varying degrees of authoritarian or libertarian tendencies. By providing a more detailed map of political beliefs, the 2D model fosters clearer communication and understanding in political discourse.

The practical application of the 2D political spectrum is evident in its use by academics, journalists, and political analysts to interpret global politics. It helps explain phenomena such as the rise of populist movements, which often blend authoritarian tendencies with left- or right-wing economic policies. Additionally, the model aids in comparing political systems across different cultures and historical periods, revealing how societies balance economic organization with personal freedoms. For example, Scandinavian social democracies are often placed in the libertarian-left quadrant due to their strong welfare states and high levels of personal freedom, while some conservative regimes might fall into the authoritarian-right quadrant.

Despite its advantages, the 2D spectrum is not without criticism. Some argue that adding more axes, such as environmentalism or globalism, could further enhance its accuracy. Others contend that political beliefs are too complex to be fully captured by any geometric model. Nonetheless, the inclusion of the authoritarian-libertarian axis represents a significant step forward in the evolution of the political spectrum. It reflects a growing recognition that economic policies and social freedoms are distinct yet interconnected dimensions of political ideology. As political landscapes continue to evolve, this expanded model remains a valuable tool for navigating the diversity of human political thought.

Can the Kennedy Center Legally Donate to Political Parties?

You may want to see also

Criticism of Spectrum: Critics argue it oversimplifies complex political beliefs and ideologies

The concept of the political spectrum, often visualized as a left-right axis, has been a cornerstone of political discourse for centuries. Its origins can be traced back to the French Revolution, where seating arrangements in the National Assembly differentiated supporters of the monarchy (right) from proponents of radical change (left). However, critics argue that this linear model oversimplifies the intricate tapestry of political beliefs and ideologies. By reducing multifaceted philosophies to a single dimension, the spectrum fails to capture the nuances and complexities inherent in political thought.

One major criticism is that the political spectrum ignores the multidimensional nature of ideologies. Political beliefs are not solely defined by economic policies (often the primary focus of the left-right axis) but also encompass social, cultural, environmental, and foreign policy dimensions. For instance, a libertarian may align with the left on social issues like drug legalization and gay rights but lean right on economic issues such as taxation and regulation. The spectrum’s unidimensional approach forces such individuals into a narrow categorization, losing the richness of their beliefs. This oversimplification can lead to misunderstandings and misrepresentations of political positions.

Another critique is that the spectrum often conflates disparate groups under broad labels, such as "left" or "right," which can obscure significant internal differences. For example, the "left" may include democratic socialists, social democrats, and communists, each with distinct visions for society. Similarly, the "right" encompasses conservatives, libertarians, and authoritarians, whose goals and methods vary widely. By grouping these ideologies together, the spectrum risks homogenizing diverse perspectives and erasing important distinctions, making it a poor tool for nuanced political analysis.

Critics also argue that the political spectrum can perpetuate false equivalencies and polarizations. The linear model suggests that positions are equally spaced and oppositional, implying that centrism is always the most balanced or correct stance. This can marginalize radical ideas that challenge the status quo, even when they address systemic issues. Furthermore, the spectrum’s emphasis on left-right opposition can exacerbate political polarization, framing politics as a zero-sum game rather than a space for dialogue and compromise. This binary thinking can hinder constructive political discourse and foster ideological rigidity.

Finally, the historical and cultural context of the political spectrum is often overlooked, leading to its misapplication in different societies. The left-right axis, rooted in Western political traditions, may not adequately represent political dynamics in non-Western contexts. For example, in some cultures, religious or ethnic identities play a more significant role in shaping political beliefs than economic policies. Applying the Western spectrum to these contexts can distort local realities and impose a foreign framework on indigenous political thought. This cultural insensitivity underscores the limitations of the spectrum as a universal tool for understanding politics.

In conclusion, while the political spectrum serves as a useful starting point for understanding political differences, its critics highlight its tendency to oversimplify complex ideologies. By neglecting multidimensionality, conflating diverse groups, perpetuating polarizations, and ignoring cultural contexts, the spectrum falls short as a comprehensive analytical tool. Recognizing these limitations is essential for developing more nuanced and inclusive approaches to political discourse.

Top Platforms for Sharing and Submitting Political Humor Online

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The concept of the political spectrum is often attributed to French politician and philosopher Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu, in the 18th century. However, the modern left-right political spectrum was popularized during the French Revolution, where seating arrangements in the National Assembly symbolized political differences.

The original purpose of the political spectrum was to categorize and simplify political ideologies based on their stance toward tradition, hierarchy, and change. During the French Revolution, the left advocated for radical change and equality, while the right supported monarchy and tradition.

Yes, the political spectrum has evolved significantly. Originally focused on left-right divisions, it now includes additional axes (e.g., authoritarian-libertarian) to account for complexities like social issues, economic policies, and global perspectives. Its interpretation varies across cultures and historical contexts.