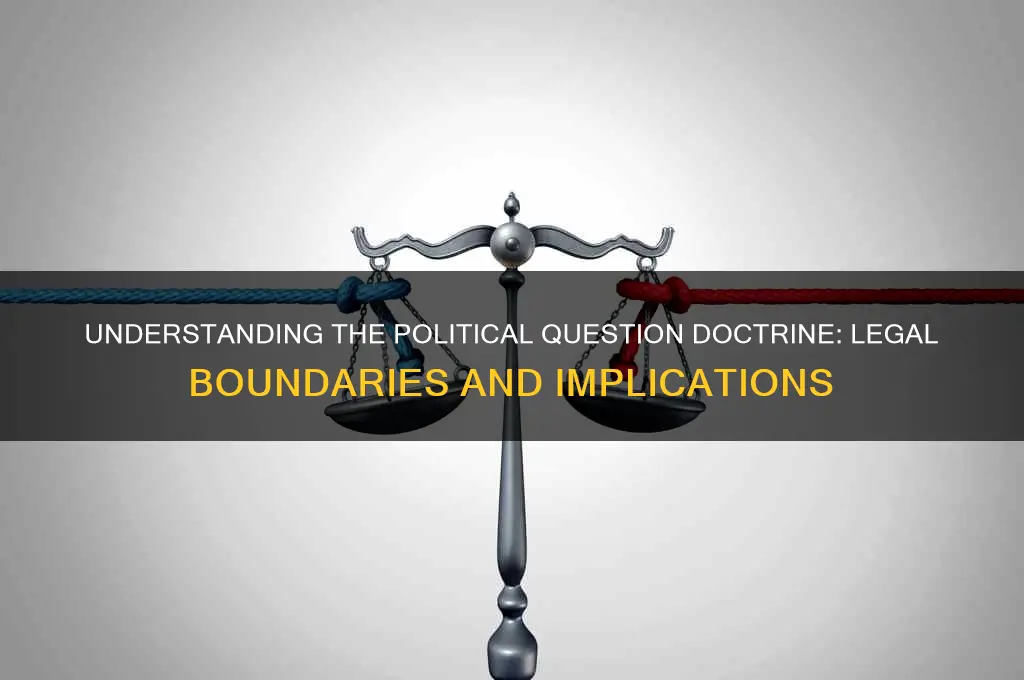

The Political Question Doctrine is a fundamental principle in constitutional law that delineates the boundary between judicially resolvable disputes and matters reserved for the political branches of government. Rooted in the separation of powers, this doctrine holds that certain issues, often involving broad policy decisions or constitutional interpretations, are inherently non-justiciable and thus beyond the purview of the courts. Courts typically invoke this doctrine when a case presents questions that lack judicially manageable standards, require policy determinations better suited for elected officials, or involve issues explicitly committed by the Constitution to another branch of government. By abstaining from such cases, the judiciary upholds the balance of power among the branches and avoids encroaching on the political process.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A judicial principle that certain political questions are non-justiciable, meaning they are not suitable for resolution by the courts. |

| Origin | Rooted in the U.S. Supreme Court case Marbury v. Madison (1803), but explicitly articulated in Coleman v. Miller (1939). |

| Key Criteria | 1. Lack of judicially discoverable and manageable standards. |

| 2. Involvement of a textually committed decision to another branch of government. | |

| 3. Impossibility of courts resolving the issue without expressing lack of respect for another branch. | |

| Purpose | To maintain separation of powers and prevent judicial interference in matters best left to the legislative or executive branches. |

| Examples of Application | - Challenges to gerrymandering (e.g., Vieth v. Jubelirer). |

| - Disputes over war powers or foreign policy. | |

| - Questions of legislative procedure or apportionment. | |

| Controversy | Critics argue it can allow unconstitutional actions to go unchecked if courts refuse to intervene. |

| Modern Relevance | Continues to be invoked in cases involving election law, executive authority, and legislative disputes. |

| Distinguishing Factor | Unlike standing or ripeness, it focuses on the nature of the issue rather than the plaintiff’s ability to sue. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins and Historical Context: Brief history of the doctrine's development in U.S. constitutional law

- Key Supreme Court Cases: Landmark rulings defining and applying the doctrine's principles

- Criteria for Application: Factors courts use to determine if a case is a political question

- Separation of Powers: Role of the doctrine in maintaining balance among government branches

- Criticism and Debate: Scholarly and legal critiques of the doctrine's scope and limitations

Origins and Historical Context: Brief history of the doctrine's development in U.S. constitutional law

The political question doctrine, a cornerstone of U.S. constitutional law, traces its origins to the early years of the American republic. Its development reflects the ongoing tension between the judiciary and the political branches of government, particularly in matters deemed inherently political or reserved for other branches. The doctrine’s roots can be found in the foundational principles of separation of powers and judicial restraint, which were implicit in the U.S. Constitution but not explicitly defined. Early Supreme Court decisions, such as *Marbury v. Madison* (1803), established the Court’s authority to review legislative and executive actions, but they also hinted at limits to judicial intervention in certain political matters. Chief Justice John Marshall’s opinion in *Marbury* emphasized that some questions are inherently inappropriate for judicial resolution, laying the groundwork for what would later be formalized as the political question doctrine.

The doctrine began to take clearer shape in the mid-19th century, as the Supreme Court grappled with cases involving contentious political issues. One of the earliest explicit articulations of the doctrine appeared in *Luther v. Borden* (1849), a case arising from a political dispute in Rhode Island. The Court declined to intervene, holding that the question of which faction constituted the legitimate state government was a political question unsuited for judicial determination. This decision underscored the judiciary’s reluctance to intrude into matters traditionally within the purview of the political branches, particularly when such issues involved complex factual determinations or required policy judgments. The *Luther* case marked a significant milestone in the doctrine’s evolution, establishing the principle that courts should refrain from deciding issues that lack judicially manageable standards.

The political question doctrine gained further clarity in the 20th century, as the Supreme Court refined its application in response to evolving constitutional and political challenges. In *Coleman v. Miller* (1939), the Court outlined a set of criteria for identifying political questions, including whether the issue involved a textually demonstrable constitutional commitment to another branch, whether there was a lack of judicially discoverable and manageable standards, or whether judicial resolution would embarrass other branches. This framework provided a more structured approach to determining when a case presented a non-justiciable political question. The decision reflected the Court’s growing recognition of the need to respect the boundaries between the judiciary and the political branches, particularly in an era of expanding federal power and complex governance.

The doctrine’s development was further shaped by Cold War-era cases, such as *Baker v. Carr* (1962), which tested its limits in the context of redistricting and the one-person, one-vote principle. While the Court held that redistricting was a justiciable issue, it reaffirmed the doctrine’s core principles and emphasized that not all political questions were beyond judicial review. This decision highlighted the doctrine’s flexibility and its role as a tool for maintaining the balance of power among the branches of government. Subsequent cases, such as *Goldwater v. Carter* (1979), involving the termination of a treaty, further illustrated the doctrine’s application to foreign policy and national security matters, areas traditionally reserved for the executive and legislative branches.

Throughout its history, the political question doctrine has served as a mechanism for preserving judicial restraint and respecting the separation of powers. Its development reflects the Supreme Court’s ongoing effort to navigate the complex interplay between law and politics, ensuring that the judiciary remains within its constitutional role while allowing the political branches to fulfill their responsibilities. While the doctrine has evolved in response to changing circumstances, its core purpose remains unchanged: to safeguard the integrity of the constitutional system by preventing judicial overreach into inherently political matters.

Will Ferrell's Political Party: Satire, Influence, and American Politics Explored

You may want to see also

Key Supreme Court Cases: Landmark rulings defining and applying the doctrine's principles

The Political Question Doctrine is a judicial principle that holds certain issues are inherently political and thus beyond the scope of judicial review. Rooted in the separation of powers, it ensures that courts do not encroach upon matters constitutionally assigned to the legislative or executive branches. Below are key Supreme Court cases that have defined and applied this doctrine, shaping its contours and limitations.

One of the earliest and most influential cases is Luther v. Borden (1849). This case arose from a dispute over Rhode Island’s state government during the "Dorr Rebellion." The Supreme Court declined to intervene, holding that the question of which entity constituted the legitimate state government was a political question reserved for Congress and the President under the Guarantee Clause of the Constitution. This ruling established the doctrine’s foundational principle: courts will not adjudicate issues that require them to interpret vague constitutional provisions or decide matters better suited for political branches.

In Coleman v. Miller (1939), the Court refined the doctrine while also outlining criteria for identifying political questions. The case involved a dispute over a state legislature’s ratification of a constitutional amendment. The Court held that the issue was justiciable because it turned on the interpretation of specific constitutional text, not broad political discretion. However, the ruling emphasized that questions involving textual ambiguity or requiring policy judgments remain non-justiciable. This case provided a framework for distinguishing between legal and political questions, ensuring courts address only those issues grounded in clear constitutional or statutory law.

Baker v. Carr (1962) marked a significant shift in the application of the Political Question Doctrine. The case challenged Tennessee’s legislative apportionment system, alleging malapportionment violated the Equal Protection Clause. The Supreme Court rejected the argument that redistricting was a political question, holding that the issue presented a justiciable legal claim. This ruling narrowed the doctrine’s scope, asserting that courts could adjudicate constitutional challenges to state actions, even in politically sensitive areas. It paved the way for the "one person, one vote" principle and expanded judicial oversight into matters previously deemed political.

Another critical case is Goldwater v. Carter (1979), which addressed the President’s authority to terminate a treaty without Senate approval. The Supreme Court dismissed the case as non-justiciable, reasoning that the Constitution’s Treaty Clause assigns the termination of treaties to the political branches. The ruling underscored the doctrine’s role in preserving executive and legislative prerogatives, particularly in foreign affairs and national security. It highlighted that courts will not intervene in disputes requiring them to second-guess political judgments or interpret ambiguous constitutional grants of power.

Finally, Vieth v. Jubelirer (2004) revisited the tension between judicial review and political questions in the context of partisan gerrymandering. The Court upheld the principle that some political questions remain beyond judicial resolution, even if they involve constitutional claims. While the majority found no manageable standard for adjudicating partisan gerrymandering, Justice Kennedy’s concurrence suggested that future standards might emerge. This case demonstrated the doctrine’s flexibility and its continued relevance in balancing judicial authority with political discretion.

These landmark cases illustrate the Political Question Doctrine’s evolution and its central role in maintaining the separation of powers. By delineating the boundaries of judicial review, the Supreme Court ensures that political disputes are resolved through democratic processes rather than judicial fiat, while still safeguarding constitutional rights and principles.

Are Political Party Donations Tax Deductible in Australia?

You may want to see also

Criteria for Application: Factors courts use to determine if a case is a political question

The political question doctrine is a principle in constitutional law that holds certain issues are inherently political and therefore non-justiciable by the courts. When determining whether a case presents a political question, courts rely on several key criteria to assess whether the issue at hand is more appropriately resolved by the legislative or executive branches rather than the judiciary. These criteria are rooted in the separation of powers and the practical limitations of judicial decision-making.

One of the primary factors courts consider is whether there is a textually demonstrable constitutional commitment of the issue to another branch of government. This means the court examines whether the Constitution explicitly assigns the authority to resolve the matter to the legislative or executive branch. For example, matters related to foreign policy, war powers, or the recognition of foreign governments are often seen as within the purview of the executive branch, as outlined in Article II of the Constitution. If the Constitution commits the issue to another branch, courts are likely to defer and find the case non-justiciable.

Another critical criterion is the lack of judicially discoverable and manageable standards for resolving the issue. Courts are institutions designed to apply legal standards and precedents, but some political questions involve policy judgments or value-laden decisions that do not lend themselves to judicial analysis. For instance, questions about the fairness of legislative redistricting or the adequacy of a government response to a crisis may require subjective assessments that courts are ill-equipped to make. In such cases, the absence of clear legal standards leads courts to conclude that the matter is a political question.

Courts also assess whether adjudicating the case would require the court to make policy decisions that are better left to elected officials. The judiciary is not a policymaking body, and cases that would necessitate judges to act like legislators or administrators are often deemed political questions. For example, determining the constitutionality of a broad economic policy or a public health measure might involve balancing competing interests, a task typically reserved for the political branches. If resolving the case would entangle the court in policymaking, it is likely to be considered non-justiciable.

Additionally, courts consider whether deciding the case would implicate the independence of the judiciary or risk undermining the legitimacy of the judicial branch. Cases that involve highly partisan or controversial issues may lead to perceptions of judicial bias or overreach, particularly if the court’s decision would be seen as usurping the role of elected officials. For instance, disputes over the certification of election results or the validity of executive actions often raise concerns about the judiciary’s role in resolving politically charged matters. In such instances, courts may decline jurisdiction to preserve their institutional integrity.

Finally, the practical consequences of judicial resolution are a significant factor. Courts may consider whether deciding the case would lead to ongoing judicial supervision of political processes or create friction between the branches. For example, if a court were to rule on the constitutionality of a legislative procedure, it might need to continually monitor compliance, blurring the lines between judicial review and legislative oversight. When the practical implications of judicial intervention are deemed too intrusive or disruptive, courts are more likely to find the case presents a political question.

In summary, the criteria courts use to determine if a case is a political question revolve around constitutional commitments, the availability of judicial standards, the nature of policy decisions, the preservation of judicial independence, and the practical consequences of intervention. These factors ensure that courts respect the separation of powers and avoid encroaching on matters best left to the political branches.

Do Focus Groups Within the Same Political Party Share Unified Views?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$28.63 $37.99

Separation of Powers: Role of the doctrine in maintaining balance among government branches

The Political Question Doctrine is a judicial principle that plays a crucial role in maintaining the delicate balance of power among the branches of government, particularly in the context of separation of powers. This doctrine holds that certain issues are inherently political and, therefore, not justiciable by the courts. Instead, these matters are best left to the elected branches of government—the legislative and executive—to resolve. By abstaining from deciding political questions, the judiciary ensures that it does not overstep its constitutional boundaries, thereby preserving the equilibrium envisioned by the separation of powers framework.

In the context of separation of powers, the Political Question Doctrine serves as a safeguard against judicial encroachment into the domains of the other branches. For instance, questions involving foreign policy, the conduct of elections, or the impeachment process are often deemed political questions. These issues require policy judgments and discretionary decisions that are better suited to the legislative and executive branches, which are accountable to the electorate. By declining to adjudicate such matters, the judiciary reinforces the principle that each branch has distinct and independent roles, preventing any one branch from dominating the others.

The doctrine also fosters accountability and responsiveness within the government. When courts refrain from intervening in political questions, they encourage the legislative and executive branches to take responsibility for their actions and decisions. This dynamic ensures that elected officials remain answerable to the public, as they cannot rely on the judiciary to resolve contentious political issues. Consequently, the Political Question Doctrine promotes a system of checks and balances where power is distributed and exercised responsibly, in line with the principles of separation of powers.

Furthermore, the Political Question Doctrine helps prevent the judiciary from becoming a political arbiter, which could undermine its legitimacy and impartiality. By limiting judicial involvement in inherently political matters, the doctrine ensures that courts focus on interpreting the law and protecting constitutional rights, rather than making policy decisions. This distinction is vital for maintaining public trust in the judiciary as an independent and nonpartisan institution. In this way, the doctrine not only upholds separation of powers but also strengthens the overall integrity of the governmental system.

Lastly, the application of the Political Question Doctrine requires careful consideration of the constitutional roles of each branch. Courts must assess whether a question is truly political, involving areas where the judiciary lacks the expertise or authority to intervene. This analysis underscores the importance of respecting the boundaries established by separation of powers. By adhering to the Political Question Doctrine, the judiciary contributes to a stable and functional government where power is shared and balanced, ensuring that no single branch can usurp the authority of the others. In essence, the doctrine is a vital tool for preserving the structural integrity of the constitutional framework.

Do Political Parties Elect Legislation? Understanding the Role of Parties in Lawmaking

You may want to see also

Criticism and Debate: Scholarly and legal critiques of the doctrine's scope and limitations

The Political Question Doctrine, rooted in the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in *Marbury v. Madison* (1803), has long been a subject of scholarly and legal critique. One major criticism centers on its lack of clear boundaries, which allows courts to evade contentious issues under the guise of judicial restraint. Critics argue that the doctrine’s vagueness enables judges to selectively determine what constitutes a "political question," potentially leading to inconsistent application and undermining judicial accountability. For instance, the doctrine’s six-factor test, outlined in *Baker v. Carr* (1962), is often seen as overly broad and subjective, leaving significant discretion to the judiciary in deciding whether to hear cases involving separation of powers, federalism, or constitutional interpretation.

Another critique focuses on the doctrine’s potential to shield governmental actions from judicial scrutiny, particularly in cases involving national security, foreign policy, or executive power. Scholars contend that this limitation can erode checks and balances, allowing the political branches to act with impunity in matters of grave constitutional importance. For example, in *Goldwater v. Carter* (1979), the Court declined to rule on the termination of a treaty, deeming it a political question, which critics argue left a critical constitutional issue unresolved and set a precedent for avoiding similar cases in the future. This raises concerns about the judiciary’s role as a guardian of constitutional rights and limits.

Legal scholars also debate whether the Political Question Doctrine aligns with democratic principles. By relegating certain issues to the political process, the doctrine may disenfranchise individuals or groups seeking redress through the courts. Critics argue that this undermines the judiciary’s role in protecting minority rights and ensuring government accountability. For instance, in cases involving voting rights or redistricting, the doctrine’s application could delay or prevent judicial intervention, potentially perpetuating systemic injustices. This tension between judicial restraint and active protection of rights remains a central point of contention.

Furthermore, the doctrine’s historical evolution and application have been criticized for reflecting political biases rather than neutral legal principles. Some argue that courts have used the doctrine to avoid controversial decisions during politically charged times, raising questions about judicial impartiality. For example, the Court’s refusal to intervene in the 2000 presidential election in *Bush v. Gore* was criticized by some as a politically motivated application of the doctrine, rather than a principled legal decision. This perception of bias undermines public trust in the judiciary and the doctrine itself.

Finally, there is ongoing debate about whether the Political Question Doctrine is necessary in modern constitutional systems. Some scholars argue that courts in other democracies routinely address politically sensitive issues without a similar doctrine, suggesting that it may be an anachronistic relic of American legal history. Others counter that the doctrine serves a vital function in maintaining the separation of powers and preventing judicial overreach. This debate highlights the need for a reevaluation of the doctrine’s scope and purpose in contemporary legal and political contexts.

In conclusion, the Political Question Doctrine remains a contentious area of constitutional law, with critiques focusing on its vagueness, potential to shield governmental actions, democratic implications, perceived biases, and overall necessity. These debates underscore the need for clearer standards and ongoing dialogue about the doctrine’s role in ensuring a balanced and accountable system of governance.

Do Political Parties Receive Taxpayer Funding? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Political Question Doctrine is a judicial principle that holds certain issues are inherently political and therefore non-justiciable, meaning they cannot be resolved by the courts but must be addressed by the legislative or executive branches of government.

Issues such as foreign policy, war powers, impeachment, and the enforcement of constitutional provisions that require political judgment or lack judicially manageable standards are often deemed political questions.

The doctrine limits the judiciary by preventing courts from deciding cases that involve questions better suited for resolution by elected officials, ensuring separation of powers and avoiding judicial overreach into political matters.

Examples include cases challenging the validity of presidential elections, disputes over the recognition of foreign governments, and questions about the constitutionality of legislative redistricting.

The doctrine is not absolute and can be subject to interpretation by the courts. However, it is deeply rooted in constitutional principles of separation of powers, making it a significant barrier to judicial intervention in political matters.