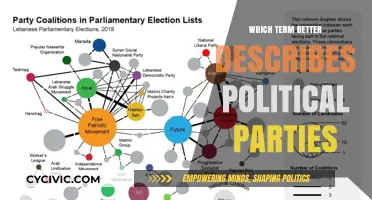

The political landscape of the United States is predominantly shaped by a two-party system, with the Democratic Party and the Republican Party holding the most significant influence and power. These two parties have historically dominated American politics, often alternating control of the presidency, Congress, and state governments. While other smaller parties, such as the Libertarian Party and the Green Party, exist and occasionally gain traction in local or state elections, their impact on national politics remains limited. The Democratic Party, generally associated with liberal policies and a focus on social welfare, and the Republican Party, typically aligned with conservative principles and limited government intervention, continue to be the primary forces driving political discourse, policy-making, and electoral outcomes in the United States.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Dominant Parties | The United States operates under a two-party system, with the Democratic Party and the Republican Party dominating politics. |

| Current Dominance | As of 2023, the Democratic Party holds the Presidency (Joe Biden) and a slim majority in the Senate, while the Republican Party holds a narrow majority in the House of Representatives. |

| Ideological Leanings | Democrats generally lean liberal/progressive, advocating for social welfare programs, progressive taxation, and social justice. Republicans lean conservative, emphasizing limited government, free markets, and traditional values. |

| Voter Base | Democrats: Urban, younger, minority, and college-educated voters. Republicans: Rural, older, white, and religious voters. |

| Key Issues | Democrats: Healthcare (e.g., Affordable Care Act), climate change, LGBTQ+ rights, and immigration reform. Republicans: Tax cuts, gun rights, border security, and deregulation. |

| Recent Trends | Increasing polarization, with both parties becoming more ideologically homogeneous and less willing to compromise. |

| Electoral College | Both parties focus heavily on swing states due to the winner-take-all system in most states. |

| Fundraising | Both parties rely heavily on corporate donations, PACs, and individual contributions, with Democrats increasingly relying on small-dollar donors. |

| Media Influence | Democrats: Associated with liberal media outlets (e.g., MSNBC, The New York Times). Republicans: Associated with conservative media (e.g., Fox News, The Wall Street Journal). |

| State Dominance | Democrats dominate coastal states (e.g., California, New York), while Republicans dominate Southern and Midwestern states (e.g., Texas, Indiana). |

Explore related products

$22.95 $22.95

What You'll Learn

- Two-Party System Dominance: Republicans and Democrats consistently dominate U.S. politics, marginalizing third parties

- Historical Evolution: From Federalists to modern parties, the U.S. system evolved into a two-party structure

- Electoral College Impact: The Electoral College favors major parties, reinforcing their dominance in presidential elections

- Third-Party Challenges: Third parties struggle due to ballot access, funding, and winner-take-all systems

- Ideological Polarization: Increasing polarization strengthens the two-party system as voters align with extremes

Two-Party System Dominance: Republicans and Democrats consistently dominate U.S. politics, marginalizing third parties

The United States operates under a two-party system where the Republican and Democratic parties have consistently dominated the political landscape for nearly two centuries. This duopoly is deeply entrenched, with third parties facing significant barriers to gaining traction or winning elections at the federal level. The last third-party candidate to win a state in a presidential election was George Wallace in 1968, and no third-party candidate has come close to winning the presidency since. This dominance is not merely a historical accident but a result of structural, cultural, and institutional factors that favor the two major parties.

One key factor perpetuating this system is the winner-take-all electoral structure in most states, where the candidate with the most votes wins all of that state’s electoral votes. This system discourages voters from supporting third-party candidates, as their votes are often seen as "wasted" or as potentially helping the candidate they least prefer. For example, in the 2000 election, Ralph Nader’s Green Party candidacy was blamed by some Democrats for siphoning votes from Al Gore, contributing to George W. Bush’s narrow victory. This dynamic creates a self-reinforcing cycle where third parties struggle to build momentum, and voters feel compelled to choose the "lesser of two evils."

Another critical barrier is the lack of federal campaign financing and media coverage for third-party candidates. The Republican and Democratic parties benefit from established fundraising networks, corporate donations, and extensive media attention, while third parties often lack the resources to compete effectively. The Commission on Presidential Debates, for instance, requires candidates to poll at 15% nationally to participate in debates, a threshold that third-party candidates rarely meet due to limited exposure. This exclusion further marginalizes their ability to reach a wider audience and gain legitimacy.

Despite these challenges, third parties have played a role in shaping U.S. politics by pushing issues into the mainstream. For example, the Progressive Party in the early 20th century advocated for women’s suffrage and labor rights, while the Libertarian Party has influenced debates on privacy and government spending. However, these contributions often occur indirectly, as third-party ideas are co-opted by the major parties rather than through direct electoral success. This dynamic underscores the resilience of the two-party system, which adapts to absorb new ideas while maintaining its dominance.

To break this cycle, structural reforms could be considered, such as ranked-choice voting or proportional representation, which would allow voters to support third parties without fear of splitting the vote. However, such changes face resistance from the established parties, which benefit from the current system. Until these barriers are addressed, the Republican and Democratic parties will likely continue to dominate U.S. politics, leaving third parties on the margins despite their potential to offer alternative perspectives and solutions.

Can Democracy Survive Without Political Parties? Exploring Alternatives and Challenges

You may want to see also

Historical Evolution: From Federalists to modern parties, the U.S. system evolved into a two-party structure

The United States’ political landscape is dominated by a two-party system, a structure that has solidified over centuries of evolution. This dominance is not merely a modern phenomenon but the culmination of historical shifts, ideological battles, and institutional adaptations. To understand how this system came to be, one must trace its roots back to the early days of the republic, when the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans laid the groundwork for partisan competition.

The Federalist Party, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, emerged in the 1790s as the first organized political party in the U.S. Advocating for a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain, the Federalists dominated the early years of the nation. However, their influence waned after the War of 1812, as their policies alienated agrarian interests and their pro-British stance became unpopular. In contrast, Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party championed states’ rights, agrarianism, and a more decentralized government. This ideological clash between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans set the stage for partisan competition, though it was far from the two-party system we recognize today.

The collapse of the Federalist Party in the early 1820s left the Democratic-Republicans as the dominant force, but internal divisions soon led to the emergence of new parties. The Democratic Party, rooted in Andrew Jackson’s populism, and the Whig Party, a loose coalition of opponents to Jackson’s policies, became the primary contenders by the 1830s. This period marked the beginning of a more stable two-party structure, though it was still fluid and prone to realignment. The Whigs’ dissolution in the 1850s, driven by irreconcilable differences over slavery, gave rise to the Republican Party, which quickly became the Democrats’ chief rival. This shift solidified the two-party framework, as regional and ideological divides increasingly aligned with one of the two major parties.

The Civil War and its aftermath further entrenched the two-party system, as the Republicans and Democrats became the primary vehicles for political expression. The Republicans, associated with the Union’s victory and Reconstruction policies, dominated the North, while the Democrats maintained a stronghold in the South. Over time, these regional identities evolved into broader ideological platforms, with the Republicans emphasizing free markets and limited government, and the Democrats advocating for social welfare and economic intervention. This dynamic persists today, though the specific issues and constituencies each party represents have shifted dramatically.

Modern political institutions and electoral rules have reinforced the two-party system. Winner-take-all elections, the Electoral College, and the lack of proportional representation make it difficult for third parties to gain traction. While minor parties like the Libertarians or Greens occasionally influence debates, they rarely win national office. This structural advantage ensures that the Republicans and Democrats remain the dominant forces, shaping policy, mobilizing voters, and defining the terms of political discourse. Understanding this historical evolution is crucial for grasping why the U.S. political system remains firmly in the grip of these two parties.

Understanding Political Party Identification: A Key Categorical Variable in Politics

You may want to see also

Electoral College Impact: The Electoral College favors major parties, reinforcing their dominance in presidential elections

The Electoral College system in the United States is a structural pillar that significantly advantages the two major political parties—the Democrats and the Republicans. This mechanism, established by the Constitution, allocates electors to each state based on its representation in Congress, with nearly all states employing a winner-take-all approach. As a result, candidates from major parties, who can mobilize resources and support across entire states, are far more likely to secure all of a state’s electoral votes, even if their victory margin is slim. This design inherently marginalizes third-party candidates, who struggle to compete in a system that rewards broad, state-wide dominance rather than proportional representation.

Consider the practical implications of this system. In battleground states like Florida or Pennsylvania, a major-party candidate can win by a fraction of a percentage point and still claim all of the state’s electoral votes. For instance, in 2016, Donald Trump won Pennsylvania by less than 1% of the vote but secured all 20 of its electoral votes. Third-party candidates, lacking the financial and organizational resources of their major-party counterparts, rarely achieve such state-wide victories, effectively shutting them out of the Electoral College calculus. This dynamic reinforces the duopoly of the Democratic and Republican parties, as voters are incentivized to support candidates with a realistic chance of winning electoral votes.

To understand the Electoral College’s impact, imagine a third-party candidate who garners significant national support but fails to win a single state. Even with, say, 10% of the popular vote, they would receive zero electoral votes, rendering their campaign electorally invisible. This outcome discourages voters from supporting third parties, as their votes would not contribute to the Electoral College tally. Over time, this cycle perpetuates the dominance of the major parties, as they remain the only viable pathways to the presidency.

A comparative analysis highlights the contrast with systems that incorporate proportional representation or ranked-choice voting, which can amplify the influence of smaller parties. In countries like Germany or New Zealand, third parties often play pivotal roles in coalition governments, reflecting a broader spectrum of voter preferences. The U.S. Electoral College, however, operates as a high barrier to entry, effectively funneling political power into the hands of the two major parties. This structural advantage is not merely a byproduct of the system but a deliberate feature that shapes the nation’s political landscape.

In conclusion, the Electoral College’s winner-take-all structure in most states creates a self-perpetuating cycle of major-party dominance. By rewarding state-wide victories and excluding proportional representation, it minimizes the electoral viability of third parties. This system not only limits voter choice but also reinforces the two-party system, ensuring that the Democrats and Republicans remain the primary contenders in every presidential election. For those seeking to challenge this dynamic, the path forward requires either fundamental reform of the Electoral College or a strategic realignment of political forces—neither of which is easily achieved.

Understanding Political Parties: Their Dual Objectives and Societal Impact

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Third-Party Challenges: Third parties struggle due to ballot access, funding, and winner-take-all systems

Third parties in the United States face an uphill battle, often struggling to gain traction in a political landscape dominated by the Democratic and Republican parties. One of the most significant hurdles is ballot access, a complex and costly process that varies by state. For instance, in Texas, third-party candidates must gather over 80,000 signatures to appear on the ballot, while in states like Vermont, the requirement is a more manageable 1,000 signatures. This disparity creates an immediate barrier, as smaller parties often lack the resources to navigate these bureaucratic mazes, effectively sidelining them before the campaign even begins.

Funding is another critical challenge. The two major parties benefit from established donor networks, corporate sponsorships, and public funding, which third parties rarely access. For example, in the 2020 election cycle, the Democratic and Republican parties raised over $1 billion each, while the Libertarian Party raised just $3.5 million. This financial disparity limits third parties’ ability to run competitive campaigns, hire staff, or purchase advertising, making it nearly impossible to reach a broad audience. Without sufficient funding, even the most compelling third-party platforms remain invisible to the majority of voters.

The winner-take-all electoral system further exacerbates these challenges. In 48 states, the presidential candidate who wins the popular vote receives all of that state’s electoral votes, marginalizing third-party candidates who rarely secure a plurality in any state. This system discourages voters from supporting third parties, as their votes are often perceived as “wasted.” For instance, Ross Perot’s 1992 campaign, which garnered nearly 19% of the popular vote, resulted in zero electoral votes. This structural disadvantage reinforces the two-party duopoly, leaving third parties with little opportunity to break through.

To overcome these obstacles, third parties must adopt strategic approaches. First, they should focus on local and state-level races, where ballot access requirements are less stringent and funding needs are lower. Success at these levels can build momentum and credibility for larger campaigns. Second, leveraging grassroots fundraising and social media can help third parties amplify their message without relying on traditional funding sources. Finally, advocating for electoral reforms, such as ranked-choice voting or proportional representation, could level the playing field by reducing the winner-take-all effect. While the path is steep, these steps offer a roadmap for third parties to challenge the dominance of the two-party system.

The Raccoon's Political Party: Uncovering a Unique Campaign Mascot

You may want to see also

Ideological Polarization: Increasing polarization strengthens the two-party system as voters align with extremes

The United States political landscape is increasingly defined by ideological polarization, a phenomenon where voters gravitate toward extreme ends of the political spectrum. This shift is not merely a reflection of differing opinions but a structural reinforcement of the two-party system. As polarization deepens, moderate voices are marginalized, and the Democratic and Republican parties solidify their dominance by absorbing these extremes. This dynamic creates a self-perpetuating cycle: polarization strengthens the two-party system, which in turn exacerbates polarization.

Consider the mechanics of this process. When voters align with ideological extremes, they are more likely to view the opposing party as not just wrong but fundamentally illegitimate. This "us vs. them" mentality discourages cross-party collaboration and reduces the appeal of third-party candidates, who struggle to gain traction in a system designed for two major parties. For instance, despite occasional surges in support for third parties, such as the Libertarian or Green Party, their impact remains minimal due to the polarized electorate’s reluctance to "waste" votes. This behavior is reinforced by electoral systems like winner-take-all, which favor the two dominant parties and penalize smaller ones.

The media plays a critical role in this polarization. News outlets and social media platforms often amplify extreme viewpoints to capture attention, creating echo chambers that reinforce ideological divides. A 2021 Pew Research study found that 73% of Americans believe social media increases political polarization by promoting content that aligns with users’ existing beliefs. This algorithmic reinforcement of extremes further drives voters into the arms of the two major parties, as moderate perspectives are drowned out by louder, more polarizing voices.

To break this cycle, practical steps can be taken. First, electoral reforms such as ranked-choice voting could incentivize candidates to appeal to a broader spectrum of voters, reducing the pressure to cater to extremes. Second, individuals can actively seek out diverse perspectives by following media sources that challenge their beliefs. For example, spending 30 minutes daily reading articles from outlets with opposing viewpoints can broaden one’s understanding and reduce the tendency to demonize the other side. Finally, political parties themselves could prioritize coalition-building over ideological purity, though this would require a significant shift in current strategies.

Ultimately, the strengthening of the two-party system through polarization is not inevitable. It is a product of structural, cultural, and behavioral factors that can be addressed. However, doing so requires a conscious effort to bridge divides and re-center political discourse. Without such efforts, the extremes will continue to dominate, leaving little room for the moderation and compromise necessary for a functioning democracy.

Exploring Alaska's Political Landscape: Which Party Dominates the Last Frontier?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The United States is dominated by a two-party system, primarily consisting of the Democratic Party and the Republican Party.

While third parties, such as the Libertarian Party or the Green Party, exist, they have limited influence and rarely win major elections due to the dominance of the two-party system.

The Democratic and Republican parties emerged as dominant forces in the mid-19th century, replacing the Whig Party and solidifying their positions through historical events, policy differences, and strategic organization.

Yes, there are regional differences; for example, the Democratic Party tends to dominate in urban areas and coastal states, while the Republican Party is stronger in rural areas and the South.

While the two-party system is deeply entrenched, changes could occur due to shifting demographics, political polarization, or the rise of significant third-party movements, though such changes would be gradual and challenging.