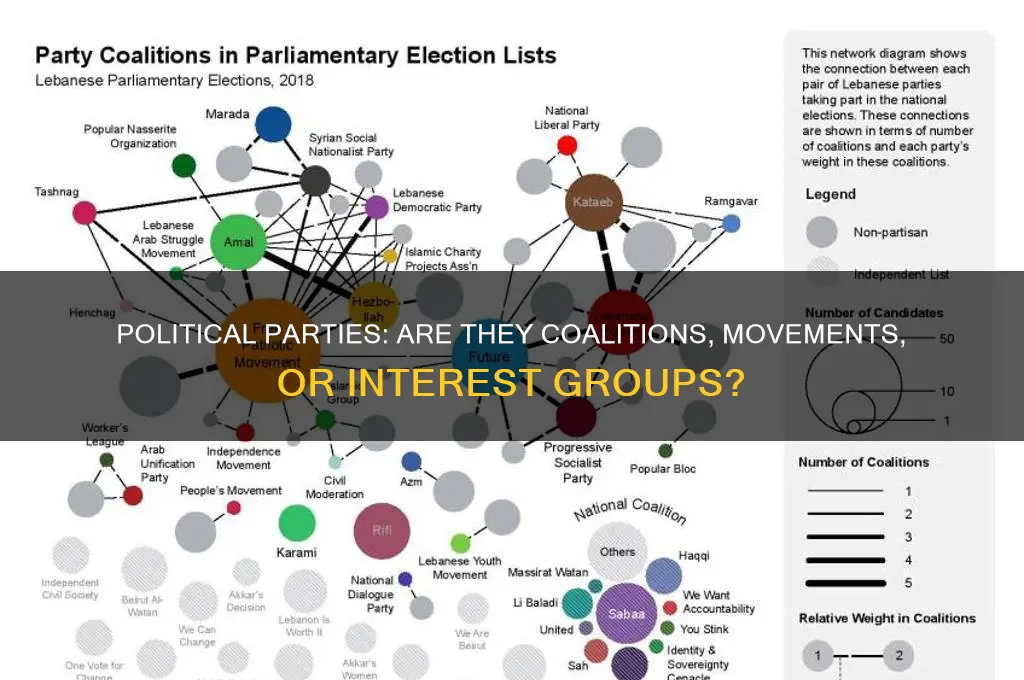

The question of which term best describes political parties is a nuanced one, as these organizations can be viewed through various lenses depending on their structure, goals, and functions. Some argue that ideological coalitions is apt, emphasizing their role in uniting individuals around shared beliefs and policy agendas. Others prefer interest groups, highlighting their function in representing specific constituencies or sectors within society. Alternatively, terms like power brokers or electoral machines underscore their strategic role in mobilizing voters and securing political influence. Each term captures a different aspect of political parties, making the choice of descriptor dependent on the context and focus of analysis.

Explore related products

$10.58 $13.75

What You'll Learn

- Ideological vs. Pragmatic: Focus on principles or practical solutions for governance and policy-making

- Elite vs. Mass-Based: Representing wealthy elites or broader public interests in decision-making

- Centralized vs. Decentralized: Strong leadership control or local autonomy in party structures

- Inclusive vs. Exclusive: Open membership policies or restricted access based on criteria

- Reactive vs. Proactive: Responding to events or shaping agendas in political landscapes

Ideological vs. Pragmatic: Focus on principles or practical solutions for governance and policy-making

Political parties often find themselves at a crossroads: should they prioritize ideological purity or embrace pragmatic solutions? This tension shapes their governance and policy-making, influencing everything from legislative agendas to public perception. Ideological parties anchor themselves to a set of core principles, often refusing to compromise even when faced with practical challenges. Pragmatic parties, on the other hand, prioritize achievable outcomes, adapting their stances to address immediate societal needs. This dichotomy raises a critical question: which approach better serves the public interest?

Consider the healthcare debate in many democracies. An ideological party might staunchly advocate for a single-payer system, arguing it aligns with principles of equality and universal access. They would likely reject incremental reforms, viewing them as insufficient or contradictory to their vision. A pragmatic party, however, might push for smaller, feasible changes—expanding Medicaid, subsidizing insurance premiums, or capping drug prices—to address immediate crises like affordability and accessibility. While the ideological approach inspires long-term vision, the pragmatic one delivers tangible, short-term benefits. For instance, Germany’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) has historically blended ideological conservatism with pragmatic policy adjustments, such as adopting green energy initiatives despite traditional pro-industry stances.

The choice between ideology and pragmatism also hinges on context. In stable, prosperous societies, ideological parties can afford to champion transformative agendas without risking systemic collapse. For example, the Green Party in countries like New Zealand or Germany has successfully pushed for ambitious environmental policies, leveraging public support for sustainability. In contrast, nations facing economic crises or political instability often require pragmatic solutions to prevent further deterioration. During the 2008 financial crisis, many governments, regardless of their ideological leanings, implemented bailouts and stimulus packages to stabilize economies, prioritizing immediate relief over long-term ideological goals.

However, the ideological-pragmatic divide is not always clear-cut. Parties often oscillate between the two, depending on political expediency or electoral pressures. For instance, the U.S. Democratic Party has both ideological wings (e.g., progressives advocating for Medicare for All) and pragmatic factions (e.g., moderates favoring incremental healthcare reforms). This internal tension can lead to policy gridlock but also fosters a balance between visionary ideals and practical governance. A useful takeaway for voters is to scrutinize not just a party’s stated principles but also its track record of implementation—does it rigidly adhere to ideology, or does it adapt to solve real-world problems?

Ultimately, the ideological vs. pragmatic debate is not about which approach is inherently superior but about which is more appropriate for the circumstances. Ideological parties provide a moral compass and long-term direction, while pragmatic parties ensure governance remains responsive to immediate needs. Striking a balance between the two—perhaps through coalition-building or internal party diversity—may be the most effective strategy. For citizens, understanding this dynamic can help in evaluating political promises and holding leaders accountable, ensuring that both principles and practical solutions guide the course of governance.

Do Absentee Ballots Favor a Specific Political Party?

You may want to see also

Elite vs. Mass-Based: Representing wealthy elites or broader public interests in decision-making

Political parties often face a fundamental tension: do they primarily serve the interests of wealthy elites or strive to represent the broader public? This dichotomy, often framed as elite vs. mass-based, shapes their policies, strategies, and ultimately, their legitimacy in the eyes of voters.

Elite-oriented parties, as the name suggests, cater to the needs and preferences of a small, affluent segment of society. They advocate for policies that protect and enhance the economic and social status of this elite group, often at the expense of broader societal welfare. For instance, tax cuts for the wealthy, deregulation of industries, and reduced social spending are hallmark policies of such parties. While these measures may stimulate economic growth, they can exacerbate inequality and leave the majority of citizens feeling disenfranchised.

A stark example is the Republican Party in the United States, which has historically been associated with pro-business, low-taxation policies that favor corporations and high-income earners. This focus on elite interests can lead to a perception of the party as out of touch with the struggles of ordinary citizens, potentially alienating a significant portion of the electorate.

In contrast, mass-based parties aim to represent the interests of the general population, advocating for policies that promote social welfare, economic equality, and democratic participation. They prioritize issues like healthcare, education, and social security, which directly impact the lives of the majority. For instance, the Nordic social democratic parties are renowned for their commitment to robust welfare states, funded by progressive taxation, ensuring a high standard of living for all citizens.

However, the challenge for mass-based parties lies in balancing the diverse interests of their broad constituency. They must navigate competing demands and make difficult trade-offs to maintain their appeal across various demographic groups. This often requires a nuanced approach to policy-making, incorporating elements of both redistribution and economic growth.

The distinction between elite and mass-based parties is not always clear-cut. Many parties exhibit a mix of these tendencies, adapting their strategies based on electoral incentives and societal changes. For instance, a party may shift its focus from elite interests to mass appeal during election campaigns, only to revert to elite-favoring policies once in power. This strategic flexibility can be both a strength and a weakness, allowing parties to adapt but also potentially eroding trust among voters.

In conclusion, the elite vs. mass-based dichotomy is a critical lens through which to analyze political parties. It highlights the inherent tension between representing specific interest groups and serving the broader public good. Understanding this dynamic is essential for voters to make informed choices and hold parties accountable for their actions, ensuring that democratic systems truly reflect the will of the people.

Lei Sharsh-Davis Political Party Affiliation: Unveiling Her Political Leanings

You may want to see also

Centralized vs. Decentralized: Strong leadership control or local autonomy in party structures

Political parties often face a structural dilemma: should power be concentrated at the top, or distributed across local branches? This centralized versus decentralized debate shapes how parties operate, make decisions, and connect with voters. Centralized structures prioritize unity and efficiency, with strong leadership controlling messaging, policy, and candidate selection. Think of the Democratic Party in the United States, where the Democratic National Committee wields significant influence over campaign strategies and party platforms. In contrast, decentralized parties grant local chapters substantial autonomy, fostering grassroots engagement but risking inconsistency. Germany’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) exemplifies this, with regional associations playing a pivotal role in shaping party direction.

Consider the trade-offs. Centralized parties can swiftly respond to crises and project a cohesive image, crucial in fast-paced political environments. However, this model may alienate local members who feel their voices are ignored. Decentralized structures, while slower to act, nurture diverse perspectives and tailor policies to regional needs. For instance, the UK’s Labour Party allows local constituencies significant say in leadership elections, though this has sometimes led to internal divisions. The choice between centralization and decentralization hinges on a party’s goals: rapid decision-making or inclusive representation.

To implement a balanced approach, parties can adopt hybrid models. For example, the Canadian Liberal Party maintains a centralized leadership for national campaigns while granting provincial wings autonomy in local issues. This blend ensures both unity and adaptability. Parties considering decentralization should start by devolving specific responsibilities, such as fundraising or candidate nominations, to local branches. Conversely, those leaning toward centralization can retain control over core functions like policy formulation while encouraging local input through advisory councils.

A cautionary note: extreme centralization risks creating a disconnect between leadership and the base, while unchecked decentralization can lead to fragmentation. Parties must regularly assess their structures through internal audits or member feedback surveys. For instance, a decentralized party might find that local chapters are misaligned with national goals, necessitating clearer communication channels. Conversely, a centralized party may discover that local enthusiasm wanes due to lack of involvement, prompting the delegation of more authority.

Ultimately, the centralized versus decentralized debate is not about choosing one extreme over the other but finding the right balance. Parties should evaluate their unique contexts—size, geographic spread, and ideological diversity—to determine the optimal distribution of power. A well-structured party adapts its model over time, ensuring it remains effective in achieving its political objectives while staying connected to its grassroots. Whether through strong leadership or local autonomy, the goal is the same: to build a resilient, responsive, and representative political organization.

Switching Political Parties in Missouri: A Step-by-Step Guide to Changing Affiliation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Inclusive vs. Exclusive: Open membership policies or restricted access based on criteria

Political parties often define themselves by who they let in—or keep out. Inclusive membership policies aim to broaden participation, fostering diversity and representation. Exclusive policies, on the other hand, prioritize ideological purity or elite control, often at the cost of accessibility. This tension shapes not only a party’s identity but also its effectiveness in mobilizing support and enacting change.

Consider the practical implications of openness. Inclusive parties, like Germany’s Pirate Party, allow anyone to join, often with minimal fees (e.g., €0–€5 annually) and no ideological tests. This approach attracts a wide range of members, from students to retirees, but can dilute the party’s core message. For instance, the Pirate Party’s focus on digital rights sometimes gets overshadowed by internal debates on unrelated issues, demonstrating the challenge of balancing diversity with coherence.

Exclusive parties, such as the British Conservative Party, impose stricter criteria—membership fees can exceed £25 annually, and applicants must align with the party’s manifesto. This ensures a more unified base but risks alienating potential supporters. In 2019, the party’s exclusionary stance on Brexit led to defections from pro-European members, illustrating how exclusivity can fracture a party’s appeal.

A comparative analysis reveals trade-offs. Inclusive policies amplify grassroots energy but may struggle to implement focused agendas. Exclusive policies streamline decision-making but risk becoming insular. For example, Spain’s Podemos party initially thrived on open membership, but as it grew, internal conflicts arose, prompting a shift toward more centralized control. This evolution underscores the need for parties to adapt their policies based on scale and context.

To navigate this dilemma, parties should adopt hybrid models. For instance, maintaining open membership while creating specialized committees for policy development can preserve inclusivity without sacrificing direction. Age-based tiers—such as discounted fees for members under 25—can attract youth without alienating older demographics. Ultimately, the goal is not to choose between inclusivity and exclusivity but to integrate their strengths, ensuring both broad appeal and strategic focus.

How Political Parties Reflect Citizens' Voices in Democracy

You may want to see also

Reactive vs. Proactive: Responding to events or shaping agendas in political landscapes

Political parties often find themselves at a crossroads: do they react to events as they unfold, or do they proactively shape the agenda? This dichotomy defines their role in the political landscape and determines their effectiveness in achieving long-term goals. Reactive parties are like firefighters, constantly putting out blazes ignited by unforeseen circumstances, while proactive parties act as architects, designing the blueprint for the future. Understanding this distinction is crucial for voters, strategists, and policymakers alike.

Consider the 2020 U.S. presidential election. The Democratic Party, led by Joe Biden, adopted a proactive stance by focusing on a detailed policy agenda addressing healthcare, climate change, and economic inequality. In contrast, the Republican Party, under Donald Trump, often appeared reactive, responding to daily controversies and shifting narratives. This example illustrates how a proactive approach can provide a clear vision, while a reactive strategy may leave a party vulnerable to external pressures. Proactive parties invest in research, polling, and long-term planning, often allocating 30-40% of their campaign budgets to agenda-setting initiatives. Reactive parties, on the other hand, may spend up to 60% of their resources on crisis management and rapid response teams.

To shift from reactive to proactive, parties must adopt a three-step strategy. First, they should establish a robust policy research unit to identify emerging trends and develop evidence-based solutions. Second, they must engage in consistent messaging, using platforms like social media to amplify their agenda. Finally, they should build coalitions with like-minded organizations to amplify their reach. For instance, the Labour Party in the U.K. successfully transitioned from a reactive stance during the 2017 election to a proactive one in 2019 by focusing on a clear manifesto centered on public services and social justice. This shift required a 20% reallocation of their campaign budget toward policy development and grassroots mobilization.

However, being proactive is not without risks. Parties that overly focus on shaping agendas may appear out of touch with immediate public concerns. For example, the French Socialist Party’s proactive push for labor reforms in 2016 faced backlash from voters who prioritized economic stability. To mitigate this, parties should balance long-term vision with short-term responsiveness, conducting quarterly public opinion surveys to gauge voter sentiment. A practical tip for party leaders is to allocate 10% of their time to engaging directly with constituents, ensuring their proactive agenda remains grounded in real-world needs.

Ultimately, the choice between reactive and proactive approaches hinges on a party’s goals and context. Reactive strategies are effective in crisis-driven environments, while proactive strategies thrive in stable, forward-looking political climates. Parties must assess their resources, voter demographics, and the political landscape to determine the optimal balance. By doing so, they can navigate the complexities of modern politics and leave a lasting impact on the issues that matter most.

Are Political Parties Essential for Democracy or Divisive Forces?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Both terms can apply, but "organizations" is more accurate as political parties are structured entities with defined leadership, membership, and goals, whereas "movements" often refer to broader, less formal social or political shifts.

Political parties are often better described as "ideologies" since they are typically founded on shared beliefs and principles, though they may also function as "coalitions" by uniting diverse groups around common goals.

"Institutions" is a more fitting term, as political parties are established, formalized entities within a political system, whereas "factions" imply smaller, less structured groups often operating within larger organizations.