Political party identification is a crucial concept in political science and sociology, often treated as a nominal variable in research. This type of variable categorizes individuals based on their self-reported affiliation with a particular political party, such as Democrat, Republican, Independent, or other. Unlike ordinal or interval variables, nominal variables do not imply any inherent order or ranking among the categories; they simply label and distinguish groups. Party identification is significant because it influences voting behavior, policy preferences, and broader political attitudes, making it a fundamental measure in understanding political polarization and public opinion. Researchers often analyze party identification using descriptive statistics, cross-tabulations, or as a predictor in regression models to explore its relationship with other political and social phenomena.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Variable | Nominal (Categorical) |

| Measurement Level | Nominal |

| Possible Values | Typically includes categories like Democrat, Republican, Independent, Other, or None |

| Mutually Exclusive | Yes (an individual usually identifies with one party at a time) |

| Exhaustive | Yes (covers all possible party identification options) |

| Order or Rank | No inherent order or ranking among categories |

| Examples of Data Collection | Surveys, polls, voter registration records |

| Common Analysis Methods | Frequency distribution, cross-tabulation, chi-square tests |

| Subject to Change | Yes (individuals can change party identification over time) |

| Cultural/Regional Variations | Yes (party labels and meanings vary by country/region) |

Explore related products

$9.53 $16.99

What You'll Learn

- Measuring Party ID: Methods to quantify political party identification, such as surveys or self-reports

- Nominal vs. Ordinal: Classifying party ID as categorical or ranked data in analysis

- Stability Over Time: Examining how party identification changes or remains constant across life stages

- Demographic Influences: Exploring how age, race, gender, and income affect party affiliation

- Party ID and Voting: Analyzing the relationship between party identification and electoral behavior

Measuring Party ID: Methods to quantify political party identification, such as surveys or self-reports

Political party identification is a nominal variable, categorizing individuals into discrete groups like Democrat, Republican, Independent, or other affiliations. Measuring this variable requires methods that capture self-reported identities accurately, as party ID is inherently subjective and based on personal alignment with a party’s values or ideology. Surveys and self-reports are the most common tools for this purpose, but their design and execution significantly influence the reliability and validity of the data collected.

Survey Design: Crafting Effective Questions

To quantify party ID, surveys typically use closed-ended questions with predefined response options. For example, respondents might be asked, “Generally speaking, do you consider yourself a Democrat, Republican, Independent, or member of another party?” This approach ensures consistency in data collection but requires careful consideration of response categories. Including an “other” or “none of the above” option accommodates less common affiliations, while follow-up questions can probe strength of identification (e.g., “Would you call yourself a strong Democrat or a leaning Democrat?”). Surveys should also account for demographic factors, as age, race, and education can influence party ID and response patterns.

Self-Reports: Leveraging Spontaneous Responses

Self-reports, often used in interviews or open-ended survey questions, allow respondents to describe their party ID in their own words. This method captures nuances that structured surveys might miss, such as hybrid identities (e.g., “I’m fiscally conservative but socially liberal”). However, self-reports require coding and categorization post-collection, introducing potential bias. Researchers must establish clear criteria for classifying responses, such as mapping “I vote Republican but don’t agree with everything they stand for” to a “leaning Republican” category.

Practical Tips for Accurate Measurement

When measuring party ID, ensure questions are placed early in surveys to avoid priming effects from preceding political topics. Use consistent phrasing across studies to enable longitudinal comparisons. For instance, the American National Election Studies (ANES) employs a standardized party ID question that has remained largely unchanged since the 1950s, facilitating trend analysis. Additionally, pilot-test questions with diverse populations to identify ambiguous wording or missing response options.

Cautions and Limitations

While surveys and self-reports are invaluable, they are not without limitations. Social desirability bias may lead respondents to align with dominant parties in their region or peer group. Temporal factors, such as election cycles or political scandals, can also skew responses. For instance, party ID may fluctuate during presidential campaigns as voters rally behind candidates. Researchers must contextualize findings with external events and consider using panel studies to track individual changes over time.

Measuring party ID requires a balance between structured surveys for scalability and self-reports for depth. By combining these methods and adhering to best practices, researchers can produce robust data that reflects the complexity of political identities. Whether analyzing national trends or local dynamics, the choice of measurement tool should align with the study’s goals, ensuring both precision and flexibility in capturing this critical political variable.

Amitabh Bachchan's Brief Political Exit: Unraveling the Reasons Behind His Departure

You may want to see also

Nominal vs. Ordinal: Classifying party ID as categorical or ranked data in analysis

Political party identification is a cornerstone of political analysis, yet its classification as a variable type is often debated. At first glance, it seems straightforward: individuals align with a party label, such as Democrat, Republican, or Independent. However, the question arises—is this alignment merely a categorical label (nominal), or does it imply a ranked preference (ordinal)? Understanding this distinction is crucial for accurate data interpretation and analysis.

Consider the nominal classification. Here, party identification is treated as a categorical variable with no inherent order. For instance, labeling someone as a Democrat or Republican is akin to categorizing them as male or female—distinct groups without a hierarchical relationship. This approach is useful for descriptive statistics, such as calculating the percentage of respondents in each category. However, it ignores any potential underlying structure or intensity of affiliation. For example, a nominal framework cannot capture whether someone is a "strong Democrat" versus a "weak Democrat," treating both as equivalent.

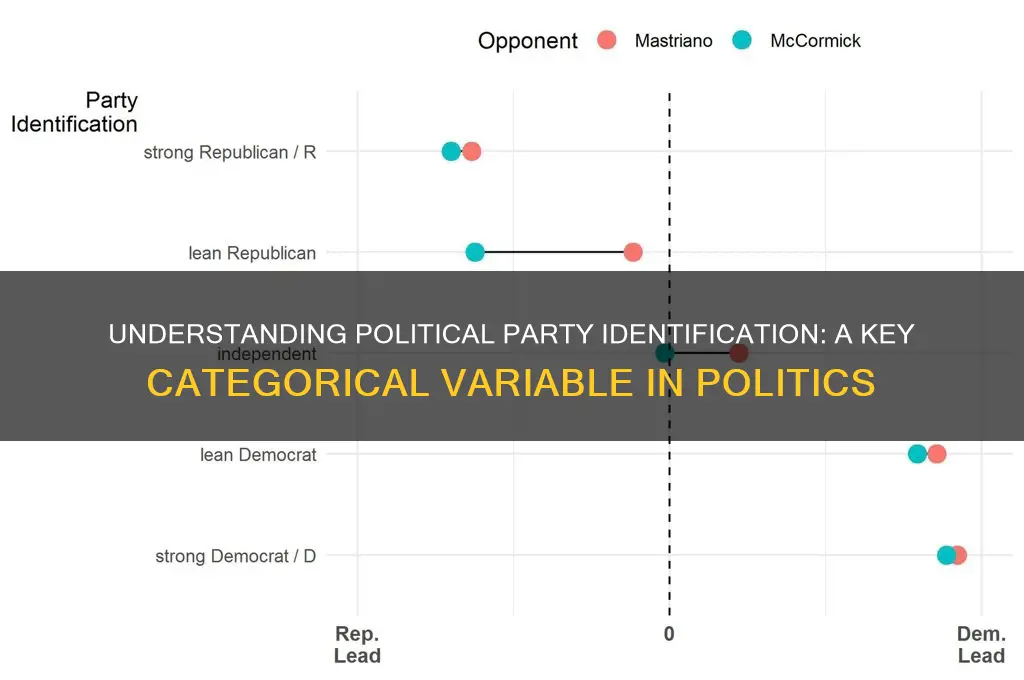

In contrast, an ordinal classification introduces a ranked order to party identification. This approach acknowledges that party affiliation may reflect varying degrees of alignment or ideological intensity. For instance, a scale could rank party ID as 1 (Strong Democrat), 2 (Weak Democrat), 3 (Independent), 4 (Weak Republican), and 5 (Strong Republican). This ordinal structure allows analysts to explore relationships between party ID and other variables, such as voting behavior or policy preferences, with greater nuance. However, it assumes that the intervals between categories are meaningful, which may not always be the case. For example, the difference between a "weak Democrat" and an "Independent" might not be quantitatively equivalent to the difference between an "Independent" and a "weak Republican."

Practical considerations further complicate this choice. Nominal classification is simpler and avoids assumptions about ranking, making it suitable for large-scale surveys where complexity is a concern. Ordinal classification, while more informative, requires careful validation to ensure the ranking reflects real-world distinctions. For instance, researchers might use follow-up questions to confirm the intensity of party affiliation, such as asking respondents to rate their agreement with party platforms on a scale of 1 to 5. This hybrid approach can provide the best of both worlds, combining categorical clarity with ordinal depth.

Ultimately, the decision to classify party ID as nominal or ordinal depends on the research question and analytical goals. If the focus is on broad group comparisons, nominal classification suffices. However, if the aim is to explore gradients of affiliation or predict behavior based on intensity, ordinal classification offers richer insights. By thoughtfully considering these options, analysts can ensure their methods align with the nuances of political party identification, enhancing the validity and utility of their findings.

Everything is Political": Unraveling the Origins of a Powerful Statemen

You may want to see also

Stability Over Time: Examining how party identification changes or remains constant across life stages

Political party identification, often treated as a nominal variable, is typically categorized as Republican, Democrat, Independent, or other. However, its stability over time transforms it into a dynamic construct, influenced by life stages and experiences. Early adulthood, marked by ages 18–25, often sees fluidity in party identification as individuals form political beliefs through education, social exposure, and initial encounters with policy impacts. For instance, college students might shift from their family’s party alignment after engaging with diverse perspectives or experiencing economic policies firsthand, such as student loan burdens.

As individuals transition into middle adulthood (ages 26–45), party identification tends to stabilize, influenced by career, family responsibilities, and homeownership. Research shows that 70% of voters in this age bracket report consistent party loyalty, often aligning with policies that directly impact their financial stability or family welfare. For example, tax policies or healthcare reforms can cement party preferences during this stage. However, major life events like economic recessions or political scandals can still trigger shifts, as seen in the 2008 financial crisis, which altered party identification for 15% of this demographic.

In later adulthood (ages 46+), party identification often becomes more rigid, with only 10% of individuals changing their political alignment. This stability is attributed to entrenched beliefs, reduced exposure to new ideas, and a focus on preserving the status quo. Retirement concerns, Social Security policies, and generational values play a significant role in maintaining party loyalty. However, unexpected events like the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that even this age group can experience shifts, particularly when policies directly affect their health and safety.

To examine these trends, longitudinal studies tracking party identification across decades provide valuable insights. For instance, the American National Election Studies (ANES) reveals that while 60% of individuals maintain their party identification from youth to old age, 40% experience at least one significant shift. Practical tips for understanding personal political evolution include reflecting on life events, tracking policy impacts over time, and engaging in intergenerational discussions to identify patterns. By analyzing these stages, individuals and researchers can better predict how party identification evolves and remains constant across the lifespan.

Understanding the Political Lens: A Framework for Analyzing Power Dynamics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$14.15 $18.99

Demographic Influences: Exploring how age, race, gender, and income affect party affiliation

Political party identification is a nominal variable, categorizing individuals into discrete groups like Democrat, Republican, or Independent. But what drives these affiliations? Demographic factors—age, race, gender, and income—play a significant role in shaping political leanings. Understanding these influences offers insight into the complex tapestry of party identification.

Age acts as a political compass, often pointing toward shifting allegiances. Younger voters, aged 18-29, tend to lean Democratic, drawn to progressive policies on issues like climate change, student debt, and social justice. This trend is evident in recent elections, where younger demographics have overwhelmingly supported Democratic candidates. As individuals age, however, party identification can shift. Middle-aged voters, aged 30-49, often prioritize economic stability and may gravitate toward the party they perceive as better equipped to handle financial concerns. Older adults, aged 50 and above, frequently exhibit stronger Republican leanings, influenced by factors like social conservatism and established political habits.

Race and ethnicity paint a vivid picture of political division. African American voters have historically shown strong Democratic support, a legacy of the Civil Rights Movement and the party's stance on racial equality. Hispanic and Latino voters, while not a monolithic bloc, also lean Democratic, influenced by immigration policies and economic opportunities. Conversely, white voters, particularly those without a college degree, have increasingly aligned with the Republican Party, driven by concerns about cultural change and economic anxieties.

Gender introduces another layer of complexity. Women, particularly younger women, are more likely to identify as Democrats, drawn to the party's positions on issues like reproductive rights, healthcare, and gender equality. Men, while still a significant portion of the Republican base, are seeing a shift, with younger men showing increased support for Democratic candidates, potentially influenced by changing societal norms and progressive ideals.

Income acts as a powerful magnet, pulling voters toward parties perceived to best serve their economic interests. Lower-income individuals often favor Democratic policies aimed at social welfare, minimum wage increases, and affordable healthcare. Higher-income earners, on the other hand, tend to lean Republican, attracted to lower taxes and deregulation. However, this trend isn't absolute; factors like education and geographic location can significantly influence how income translates into party affiliation.

Understanding these demographic influences is crucial for predicting voting patterns, crafting effective political strategies, and fostering a more inclusive political landscape. By recognizing the diverse factors shaping party identification, we can move beyond simplistic stereotypes and engage in more nuanced discussions about the complexities of political affiliation.

Exploring Georgia's Political Landscape: Active Parties and Their Influence

You may want to see also

Party ID and Voting: Analyzing the relationship between party identification and electoral behavior

Political party identification, often referred to as Party ID, is a cornerstone of political behavior studies, serving as a nominal variable that categorizes individuals based on their self-reported affiliation with a political party. Unlike ordinal or interval variables, Party ID does not imply a hierarchy or measurable distance between categories; instead, it reflects distinct groups—Democrats, Republicans, Independents, and others. This classification is critical for understanding electoral behavior, as it often predicts voting patterns more consistently than demographic factors alone. For instance, in the 2020 U.S. presidential election, 93% of voters who identified as Democrats cast their ballots for Joe Biden, while 94% of Republicans voted for Donald Trump, according to Pew Research Center. This stark alignment underscores the predictive power of Party ID in electoral outcomes.

To analyze the relationship between Party ID and voting behavior, researchers employ both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Cross-sectional analyses examine Party ID and voting behavior at a single point in time, revealing immediate correlations. For example, exit polls consistently show that Party ID is the strongest predictor of vote choice, even when controlling for age, race, gender, and income. Longitudinal studies, on the other hand, track changes in Party ID over time and their impact on voting. A notable trend is the increasing polarization of Party ID, where individuals are less likely to switch affiliations and more likely to vote along party lines. This rigidity has deepened the divide between Democrats and Republicans, with Independents often leaning toward one party, effectively behaving as "soft partisans."

Practical tips for interpreting Party ID data include distinguishing between "strong" and "weak" identifiers. Strong identifiers are more likely to vote in primaries, donate to campaigns, and engage in political activism, making them a critical subgroup for campaign strategists. Weak identifiers, while less engaged, still tend to vote along party lines in general elections. For instance, in the 2018 midterms, 90% of strong Democrats and 86% of strong Republicans voted for their party’s candidate, compared to 78% of weak identifiers, according to the American National Election Studies. Campaigns can leverage this insight by targeting strong identifiers for mobilization efforts and weak identifiers for persuasion strategies.

A cautionary note is warranted when analyzing Party ID in diverse electoral contexts. In multiparty systems, such as those in Europe, Party ID may be less predictive of voting behavior due to the presence of coalition governments and proportional representation. For example, in Germany, voters often split their ballots between parties for the federal and state levels, complicating the direct link between Party ID and vote choice. Additionally, the rise of populist and niche parties has introduced volatility into Party ID, as voters may shift affiliations based on specific issues rather than long-standing ideological alignment. Researchers must therefore account for systemic differences when generalizing findings across countries.

In conclusion, Party ID is a nominal variable that plays a pivotal role in shaping electoral behavior, particularly in two-party systems like the United States. Its predictive strength lies in its ability to categorize voters into distinct groups with consistent voting patterns. However, nuances such as the distinction between strong and weak identifiers and the influence of electoral systems require careful consideration. By understanding these dynamics, analysts can better predict voter behavior, inform campaign strategies, and interpret election outcomes with greater precision.

Are Political Parties Constitutionally Defined? Exploring Legal Frameworks and Roles

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political party identification is typically considered a categorical or nominal variable because it represents categories or labels (e.g., Democrat, Republican, Independent) without any inherent order or ranking.

While political party identification is usually nominal, it can sometimes be treated as an ordinal variable if the categories are arranged in a meaningful order (e.g., Liberal < Moderate < Conservative). However, this depends on the context and specific research design.

No, political party identification is not a continuous variable. It does not measure a quantitative or numerical value but rather discrete categories, making it unsuitable for continuous variable analysis.