From 1932 until 1968, the Democratic Party dominated American politics, largely due to the transformative leadership of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the enduring legacy of his New Deal programs. Roosevelt's election in 1932 marked the beginning of a significant shift in political power, as he implemented sweeping economic and social reforms to combat the Great Depression. The Democratic Party's dominance was further solidified by its ability to build a broad coalition of voters, including labor unions, ethnic minorities, and Southern conservatives, known as the New Deal coalition. This coalition helped the Democrats maintain control of the presidency for most of this period, with only two Republican presidents, Eisenhower and Nixon, briefly interrupting their reign. The party's influence extended beyond the presidency, as they also held majorities in Congress for much of this era, shaping key legislation and policies that defined mid-20th century America.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Party | Democratic Party (United States) |

| Period of Dominance | 1932–1968 |

| Key Leaders | Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Ideological Orientation | Liberal, Progressive, New Deal Coalition |

| Major Policies | New Deal, Social Security, Civil Rights Act (1964), Great Society Programs |

| Electoral Strength | Controlled the Presidency for most of the period, strong majorities in Congress |

| Base of Support | Urban voters, labor unions, African Americans, Southern conservatives (until 1960s) |

| Economic Focus | Government intervention, welfare programs, economic regulation |

| Foreign Policy | Leadership in World War II, Cold War containment, alliances (NATO) |

| Social Impact | Expansion of civil rights, social safety nets, cultural liberalism |

| Decline Factors | Vietnam War backlash, civil rights tensions, shift in Southern voters |

Explore related products

$24.99

What You'll Learn

FDR's New Deal Coalition

The Democratic Party's dominance from 1932 to 1968 hinged on Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal Coalition, a strategic alliance that reshaped American politics. This coalition united diverse groups—urban workers, ethnic minorities, Southern whites, intellectuals, and farmers—under a common banner of economic reform and social welfare. By addressing the widespread suffering caused by the Great Depression, FDR not only secured repeated electoral victories but also established a political realignment that lasted for decades.

Consider the mechanics of this coalition. FDR's New Deal programs, such as Social Security, the Works Progress Administration, and the National Recovery Administration, provided tangible benefits to millions. For urban workers, these programs meant jobs and financial security. For farmers, agricultural subsidies and price controls offered relief from economic ruin. Southern whites, traditionally Democratic, remained loyal due to the party's historical ties and the region's dependence on federal aid. Meanwhile, intellectuals and progressives were drawn to the New Deal's vision of an active, interventionist government. Each group had distinct reasons for supporting the Democrats, yet FDR's leadership kept them united.

However, the coalition's strength also contained the seeds of its eventual fracture. The inclusion of Southern conservatives, who opposed civil rights reforms, clashed with the growing demands of African American voters and Northern liberals. This tension became increasingly evident in the 1960s, as the Democratic Party struggled to balance its commitment to racial equality with its reliance on segregationist Southern support. FDR's coalition, while durable, was built on compromises that would ultimately prove unsustainable.

To understand the New Deal Coalition's impact, examine its legacy in modern politics. It laid the groundwork for the modern welfare state and redefined the role of government in American life. Yet, it also highlights the challenges of maintaining a broad-based political alliance in a rapidly changing society. For anyone studying political strategy, the New Deal Coalition offers a masterclass in coalition-building—but also a cautionary tale about the limits of compromise. Practical takeaway: Successful coalitions require not only shared interests but also a clear, adaptable vision that can evolve with societal demands.

Is Suffrage a Political Party? Debunking Misconceptions and Understanding Its Role

You may want to see also

Democratic Party's Southern Base

The Democratic Party's dominance from 1932 to 1968 was deeply rooted in its Southern base, a region that provided a solid electoral foundation during this period. This dominance, however, was not merely a numbers game but a complex interplay of historical, cultural, and political factors. The South's loyalty to the Democratic Party was a legacy of the Civil War and Reconstruction, where the party was seen as the defender of states' rights and Southern traditions against what was perceived as Northern aggression. This historical allegiance was further solidified by Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal policies, which brought significant economic relief to the impoverished South, fostering a sense of gratitude and political loyalty.

To understand the mechanics of this dominance, consider the electoral strategy employed by the Democratic Party. The Solid South, as it was often called, was a bloc of states that consistently voted Democratic in presidential elections. This reliability allowed the party to focus its campaign efforts on swing states in the North and Midwest, knowing that the South would deliver its electoral votes without extensive campaigning. For instance, in the 1948 election, Harry S. Truman won the presidency with a significant portion of his electoral votes coming from the South, despite facing a strong challenge from third-party candidates.

However, the Democratic Party's Southern base was not without its internal tensions. The party had to navigate the competing interests of its conservative Southern wing and its more progressive Northern and Western factions. This balancing act often involved compromising on civil rights issues to maintain Southern support. For example, while the party's national platform began to embrace civil rights more openly in the 1940s and 1950s, Southern Democrats frequently resisted these changes, leading to the emergence of the "Dixiecrat" movement in 1948, which sought to preserve segregation and states' rights.

The practical implications of this Southern dominance were far-reaching. It influenced legislative priorities, with Southern Democrats holding key committee chairmanships in Congress, particularly in areas like agriculture and appropriations. This allowed them to direct federal funds and policies in ways that benefited the South, such as through agricultural subsidies and infrastructure projects. However, this power also meant that progressive legislation, especially on civil rights, often faced significant hurdles, as Southern Democrats used their influence to block or weaken such measures.

In conclusion, the Democratic Party's Southern base was a double-edged sword. While it provided the electoral stability needed to dominate national politics for decades, it also constrained the party's ability to fully embrace progressive reforms, particularly on civil rights. This tension ultimately contributed to the realignment of American politics in the late 1960s, as the Democratic Party's commitment to civil rights under Lyndon B. Johnson began to alienate its traditional Southern base, paving the way for the rise of the Republican Party in the South. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for anyone seeking to comprehend the political shifts that have shaped modern American politics.

Rebecca Dallet's Political Affiliation: Uncovering Her Party Ties

You may want to see also

Liberal vs. Conservative Factions

From 1932 to 1968, the Democratic Party dominated American politics, holding the presidency for 24 out of 36 years. This era, often referred to as the "New Deal Coalition," saw the party’s liberal faction reshape the nation’s economic and social policies. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, aimed at recovering from the Great Depression, became the cornerstone of Democratic ideology, emphasizing government intervention, social welfare, and labor rights. Yet, within this dominant party, a tension emerged between its liberal and conservative factions, each vying to define the party’s direction and priorities.

The liberal faction, led by figures like Roosevelt, Harry Truman, and later John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, championed progressive reforms. They pushed for civil rights legislation, expanded social safety nets, and increased federal spending on education and healthcare. For instance, Johnson’s Great Society programs in the 1960s aimed to eliminate poverty and racial injustice, culminating in landmark laws like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Liberals within the party saw government as a tool for social justice, advocating for policies that addressed systemic inequalities. Their approach was analytical, focusing on data-driven solutions to societal problems, and persuasive, framing their agenda as a moral imperative for a more equitable nation.

In contrast, the conservative faction, often referred to as the "Dixiecrats," was rooted in the South and resisted many of the liberal agenda’s key components. These Democrats, such as Senator Richard Russell of Georgia, opposed federal intervention in state affairs, particularly on issues like desegregation and voting rights. They prioritized fiscal conservatism, states’ rights, and traditional social values, often aligning with Republicans on economic issues. This faction’s resistance to civil rights legislation led to frequent clashes within the party, with conservatives employing procedural tactics like filibusters to stall progressive reforms. Their stance was instructive, warning of the dangers of overreaching federal power and advocating for a return to local control.

The tension between these factions reached a breaking point during the 1960s, as the liberal agenda gained momentum. The passage of civil rights laws alienated many Southern conservatives, who began to shift their allegiance to the Republican Party. This realignment was evident in the 1968 election, when conservative Democrat George Wallace ran as a third-party candidate, appealing to voters who felt abandoned by the party’s liberal turn. The comparative analysis of these factions reveals how ideological divides within a dominant party can lead to its fragmentation, ultimately reshaping the political landscape.

Practical takeaways from this era highlight the importance of balancing unity and diversity within a political party. While the Democratic Party’s liberal faction achieved significant progress, its failure to address the concerns of its conservative wing contributed to its decline in the South. For modern political strategists, this serves as a cautionary tale: ignoring internal factions can lead to long-term electoral consequences. To maintain dominance, parties must foster dialogue between factions, seek common ground, and adapt policies to reflect the diverse values of their base. This descriptive approach underscores the fragility of political coalitions and the need for inclusive leadership.

Did the USSR Legalize Other Political Parties? Exploring Soviet Politics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$21.95

$26.55 $27.95

$48.63 $63.99

Republican Challenges and Rebounds

The Democratic Party's dominance from 1932 to 1968 was not without its challenges, and the Republican Party's ability to rebound during this period offers valuable insights into political resilience. Despite being largely out of power at the federal level, the GOP managed to maintain influence through strategic adaptations and localized successes. This section explores the Republican Party's challenges and rebounds, highlighting key moments, strategies, and lessons that shaped their trajectory during this era.

One of the most significant challenges Republicans faced was the enduring popularity of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, which redefined the role of government and solidified Democratic support among key demographics, including labor unions, urban voters, and the working class. To counter this, Republicans adopted a dual strategy: first, they sought to appeal to conservative Democrats disillusioned with the expanding federal government, and second, they emphasized fiscal responsibility and limited government. This approach gained traction in the 1946 midterms, where Republicans regained control of Congress by campaigning against post-war economic challenges and perceived Democratic overreach. This rebound demonstrated the effectiveness of framing elections around economic concerns and government accountability.

However, the Republican Party's success was often short-lived, as they struggled to unify their moderate and conservative factions. The 1952 and 1956 presidential victories of Dwight D. Eisenhower exemplified this tension. Eisenhower, a moderate, appealed to a broad electorate but alienated the party's conservative base, which viewed his policies as too accommodating to New Deal programs. This internal divide resurfaced in the 1964 election, when Barry Goldwater's conservative candidacy energized the base but alienated moderates, resulting in a landslide defeat. The lesson here is clear: balancing ideological purity with electoral viability is critical for sustained political success.

Despite these setbacks, Republicans found opportunities to rebound by capitalizing on Democratic missteps and shifting public sentiment. For instance, the party effectively criticized Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society programs as fiscally irresponsible and exploited growing public discontent over the Vietnam War. These critiques laid the groundwork for Richard Nixon's 1968 victory, which marked the beginning of a new Republican era. Nixon's "Southern Strategy" and appeal to "silent majority" voters further demonstrated the GOP's ability to adapt and exploit emerging political trends.

In practical terms, Republican rebounds during this period underscore the importance of flexibility, messaging, and coalition-building. Parties must be willing to evolve their platforms to address changing voter priorities while maintaining core principles. For modern political strategists, studying this era offers a roadmap for navigating dominance by an opposing party: identify vulnerabilities, craft targeted messages, and build coalitions that transcend ideological divides. By doing so, even a party out of power can position itself for future success.

Which Political Party Holds the Majority in Parliament Today?

You may want to see also

Civil Rights Era Shifts

The Democratic Party's dominance from 1932 to 1968 was rooted in Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal coalition, which united Southern conservatives, Northern liberals, urban workers, and rural farmers. However, the Civil Rights Era of the 1950s and 1960s exposed deep fractures within this coalition, particularly over racial equality. As the national Democratic Party increasingly embraced civil rights legislation, Southern Democrats, who had long relied on segregationist policies, began to defect. This ideological shift marked the beginning of a realignment that would reshape American politics for decades.

Consider the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, both championed by Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson. These landmark laws dismantled Jim Crow segregation and protected the voting rights of African Americans. While these measures were celebrated by Northern liberals and African American voters, they were vehemently opposed by many Southern Democrats. The famous quip by President Johnson to an aide—"We have lost the South for a generation"—proved prophetic. Southern Democrats, feeling betrayed by their national party, began to gravitate toward the Republican Party, which was increasingly adopting a "Southern Strategy" to appeal to conservative white voters.

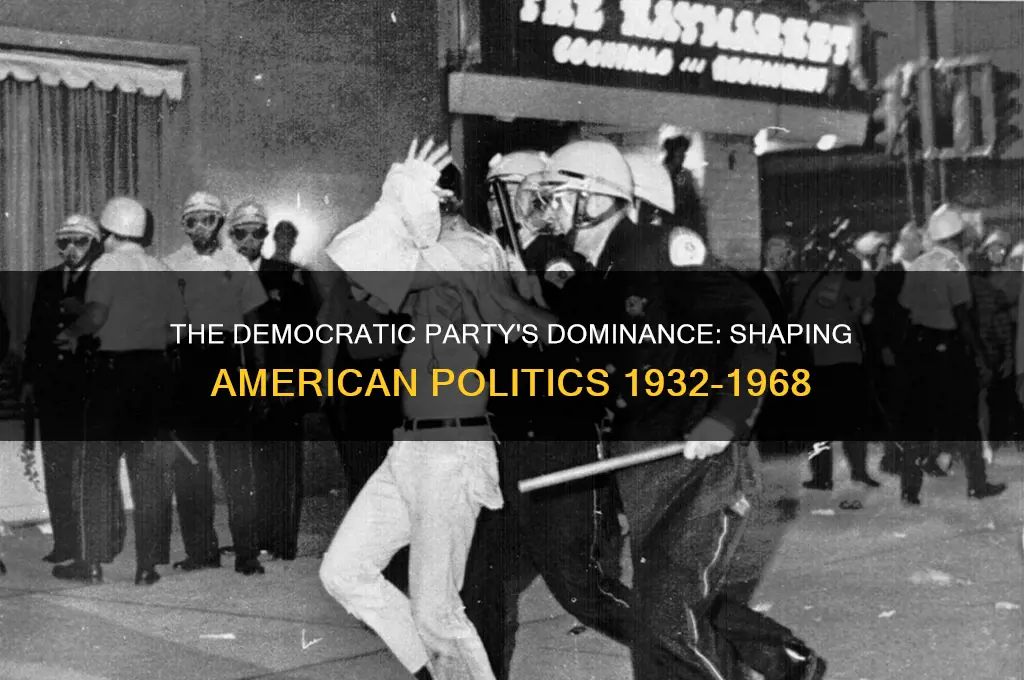

This shift was not immediate, but it was inexorable. The 1968 presidential election serves as a pivotal moment in this transition. Democratic candidate Hubert Humphrey, who supported civil rights, faced a challenge from segregationist George Wallace, running as an independent. Meanwhile, Republican Richard Nixon capitalized on white backlash to civil rights, using coded language about "law and order" to appeal to disaffected Southern Democrats. The election results reflected this realignment: while Humphrey won the national election, Nixon made significant inroads in the South, foreshadowing the region's eventual shift to Republican dominance.

To understand the practical implications of this shift, examine voter migration patterns. Between 1952 and 1968, the Democratic Party's share of the Southern white vote plummeted from 70% to 30%. Conversely, the Republican Party saw a corresponding rise in Southern support. This realignment was not just about race; it also involved economic and cultural issues. Southern conservatives felt alienated by the Democratic Party's growing emphasis on social welfare programs and its association with urban, liberal elites. The Civil Rights Era, therefore, acted as a catalyst for a broader political transformation, breaking apart the New Deal coalition and setting the stage for the modern partisan divide.

In conclusion, the Civil Rights Era shifts within the Democratic Party from 1932 to 1968 were not merely about policy changes but represented a fundamental reordering of American political alliances. The party's commitment to civil rights alienated its Southern conservative base, driving them into the arms of the Republican Party. This realignment had lasting consequences, reshaping the electoral map and redefining the ideological contours of both major parties. Understanding this period offers critical insights into the enduring dynamics of race, region, and partisanship in American politics.

Understanding AC's Political Affiliation: Unraveling the Party Connection

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Democratic Party dominated American politics during this period, largely due to the New Deal coalition built by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The election of Franklin D. Roosevelt as President in 1932 marked the beginning of Democratic dominance, as his New Deal policies reshaped American politics and solidified Democratic support.

The New Deal coalition united diverse groups, including labor unions, ethnic minorities, Southern whites, and urban voters, creating a broad base of support that sustained Democratic dominance for decades.

Yes, Republicans won the presidency twice during this era—in 1952 and 1956 with Dwight D. Eisenhower—but the Democratic Party maintained control of Congress for most of the period.

The decline of Democratic dominance after 1968 was influenced by internal party divisions over civil rights, the Vietnam War, and the rise of the conservative movement, which shifted the political landscape in favor of the Republican Party.