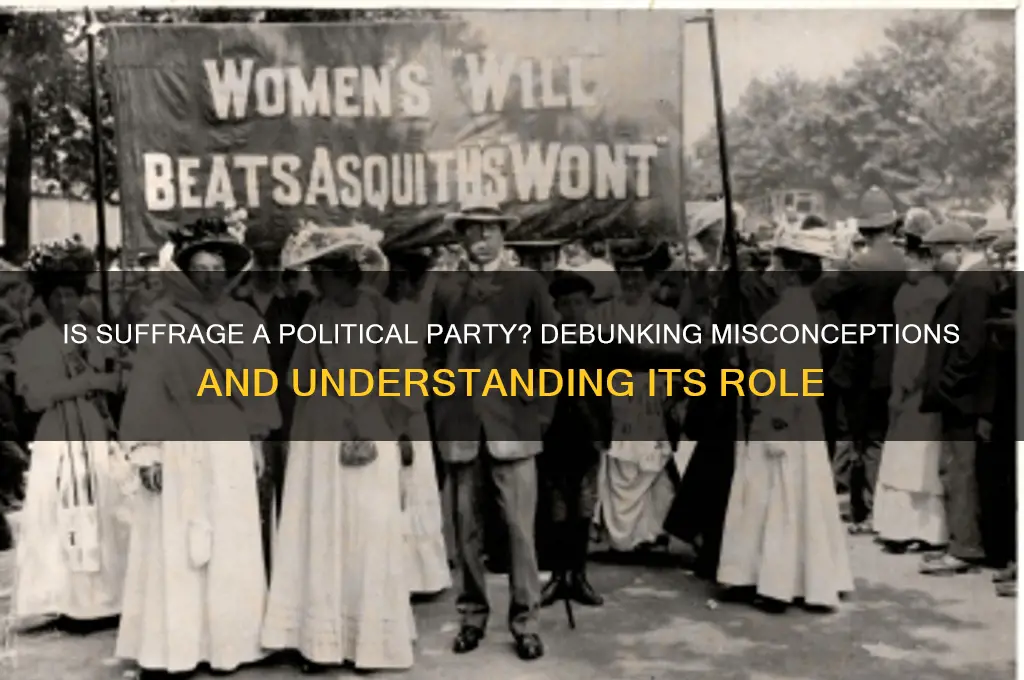

The question of whether suffrage constitutes a political party is a nuanced one, as suffrage itself is fundamentally a movement advocating for the right to vote, rather than a formal political organization. Historically, suffrage movements, such as those led by women in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, were coalitions of diverse individuals and groups united by a common goal: securing voting rights for marginalized populations. While these movements often influenced political parties and shaped policy agendas, they were not structured as parties with candidates, platforms, or hierarchical leadership. Instead, suffrage functioned as a broader social and political cause, transcending party lines to mobilize public support and drive legislative change. Thus, while suffrage movements have had profound political impacts, they are more accurately described as advocacy efforts rather than political parties.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Suffrage Movement Origins

The suffrage movement, often misunderstood as a political party, is actually a broad social and political campaign that emerged in the 19th century to secure the right to vote for marginalized groups, primarily women. Its origins are deeply rooted in the fight for equality and justice, transcending party lines to challenge systemic oppression. While suffrage organizations often collaborated with political parties, their core mission was to dismantle barriers to voting rights, not to establish a party of their own. This distinction is crucial for understanding the movement’s impact and legacy.

Analytically, the origins of the suffrage movement can be traced to the intersection of Enlightenment ideals and the Industrial Revolution. The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw a surge in discussions about natural rights and equality, fueled by thinkers like Mary Wollstonecraft, whose *A Vindication of the Rights of Woman* (1792) laid the groundwork for feminist thought. Simultaneously, industrialization brought women into factories and public life, exposing them to economic exploitation and sparking demands for political representation. The 1848 Seneca Falls Convention in the United States, organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, marked a pivotal moment, where the *Declaration of Sentiments* explicitly demanded women’s right to vote. This event exemplifies how the movement emerged from a blend of intellectual ferment and practical grievances.

Instructively, the early suffrage movement employed diverse tactics to advance its cause, offering lessons for modern activism. Petitions, public lectures, and publications were central to raising awareness, while more radical strategies, such as hunger strikes and civil disobedience, gained prominence in the early 20th century. For instance, the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in the UK, led by Emmeline Pankhurst, adopted the motto “Deeds not Words,” engaging in acts of defiance like window-breaking and arson to draw attention to their cause. These methods, though controversial, underscore the movement’s adaptability and determination. Aspiring activists can learn from this history by balancing traditional advocacy with bold, attention-grabbing actions tailored to their context.

Comparatively, the suffrage movement’s origins highlight its global nature, though it is often associated with Western countries. In New Zealand, women gained the right to vote in 1893, becoming the first self-governing nation to do so, thanks to the efforts of Kate Sheppard and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. In contrast, Finland granted women full political rights in 1906, influenced by its unique political landscape under Russian rule. These examples demonstrate how the movement adapted to local conditions, leveraging existing social structures and alliances. This global perspective challenges the notion of suffrage as a singular, Western-centric phenomenon, revealing its universal aspirations and varied manifestations.

Descriptively, the origins of the suffrage movement were marked by resilience in the face of opposition. Early suffragists endured ridicule, imprisonment, and violence for their activism. In the UK, the “Cat and Mouse Act” of 1913 allowed hunger-striking prisoners to be temporarily released, only to be re-arrested once they recovered—a brutal tactic to suppress dissent. Similarly, in the U.S., African American women like Ida B. Wells faced dual discrimination, fighting for suffrage while confronting racism within the movement itself. These struggles illustrate the movement’s tenacity and the personal sacrifices made by its pioneers. Their stories serve as a reminder that progress often requires enduring hardship and confronting injustice head-on.

Toyota's Political Donations: A Bipartisan Approach or Strategic Balance?

You may want to see also

Political Party Involvement

Suffrage, the right to vote, is fundamentally a civic principle rather than a political party. However, political parties have historically played a pivotal role in advocating for and shaping suffrage movements. Understanding this involvement requires examining how parties have leveraged suffrage as a tool for power, mobilized voters, and influenced legislative outcomes.

Consider the 19th-century women’s suffrage movement in the United States. The Republican Party strategically supported the 19th Amendment to gain female voters, particularly in the post-Civil War era. This example illustrates how parties can instrumentalize suffrage to expand their electoral base. Conversely, the Democratic Party in the South often opposed suffrage for women and minorities to maintain political control. Such historical dynamics reveal that party involvement in suffrage is often driven by self-interest rather than altruism. Analyzing these patterns helps explain why suffrage expansions frequently align with shifts in political power.

To engage effectively with political parties on suffrage issues, activists must adopt a multi-pronged strategy. First, identify parties or factions within parties that align with suffrage goals. For instance, third-party movements like the Progressive Party in the early 20th century often championed suffrage when major parties hesitated. Second, pressure parties through grassroots campaigns, leveraging voter turnout as a bargaining chip. Third, educate voters on party stances to hold them accountable. Practical tips include tracking party platforms, attending town halls, and using social media to amplify suffrage-related demands.

Comparing global suffrage movements highlights the diversity of party involvement. In New Zealand, cross-party collaboration led to women’s suffrage in 1893, while in the UK, the Labour Party’s rise in the early 20th century accelerated suffrage reforms. In contrast, some countries, like Saudi Arabia, have seen suffrage expansions driven by royal decrees rather than party politics. These examples underscore that party involvement varies by context, influenced by cultural norms, political systems, and historical legacies.

Ultimately, while suffrage itself is not a political party, parties are indispensable actors in its realization. Their involvement can either accelerate or hinder progress, depending on strategic interests and external pressures. Activists and citizens must navigate this landscape by understanding party motivations, leveraging voter power, and fostering alliances. By doing so, they can transform suffrage from a theoretical right into a practical tool for democratic participation.

Who Benefits from Politics? Unveiling Power, Privilege, and Inequality

You may want to see also

Women's Suffrage Campaigns

Suffrage, by definition, refers to the right to vote in political elections, not a political party itself. However, women’s suffrage campaigns often operated within the political landscape, forming alliances, lobbying parties, and even creating their own organizations to achieve their goals. These campaigns were not monolithic; they varied in strategy, tone, and scope across different countries and eras. For instance, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) in the United States, led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, focused on a federal amendment, while the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) prioritized state-by-state efforts. Understanding these campaigns requires examining their tactics, challenges, and legacies.

Consider the analytical perspective: Women’s suffrage campaigns were masterclasses in strategic adaptation. In Britain, the suffragettes, led by Emmeline Pankhurst, employed militant tactics like hunger strikes and property damage to draw attention, while the suffragists, led by Millicent Fawcett, favored peaceful lobbying and petitions. This duality highlights the tension between radicalism and gradualism in political movements. In contrast, New Zealand’s suffrage campaign, which succeeded in 1893, relied on grassroots organizing and cross-party support, demonstrating that context-specific strategies can yield faster results. The takeaway? Effective campaigns tailor their methods to their political environment, balancing pressure and persuasion.

From an instructive standpoint, organizing a suffrage campaign requires clear goals, diverse coalitions, and sustained effort. Start by identifying key allies—whether labor unions, religious groups, or sympathetic politicians—and build a broad base of support. Leverage multiple channels: petitions, public speeches, and media coverage. For example, the use of parades, like the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington, D.C., combined visibility with cultural appeal. Caution: Avoid alienating potential supporters through extreme tactics. Instead, focus on educating the public and countering misinformation. Practical tip: Use data to highlight disparities in voting rights and frame suffrage as a matter of justice, not just gender.

A comparative analysis reveals that women’s suffrage campaigns often mirrored broader political struggles. In India, suffrage was intertwined with the fight for independence from British rule, with leaders like Sarojini Naidu linking gender equality to national liberation. In contrast, Scandinavian countries like Finland and Norway achieved women’s suffrage as part of broader social democratic reforms. This comparison underscores how suffrage campaigns can either align with or challenge existing power structures. The key lesson? Suffrage movements are most successful when they connect their cause to wider societal aspirations, whether democracy, equality, or freedom.

Finally, from a descriptive viewpoint, women’s suffrage campaigns were fueled by resilience in the face of adversity. Activists endured ridicule, imprisonment, and violence, yet persisted through decades of struggle. Take the case of Alice Paul, who led the Silent Sentinels in picketing the White House during World War I, demanding suffrage while the nation focused on war efforts. Their stories remind us that progress often requires sacrifice and unwavering commitment. To emulate their success, modern advocates should embrace persistence, creativity, and a willingness to challenge the status quo. After all, the right to vote was never gifted—it was fought for, inch by inch.

Why Political Parties Host National Conventions: Purpose and Impact Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Suffrage and Democracy Links

Suffrage, the right to vote, is fundamentally a cornerstone of democracy, not a political party. It is the mechanism through which citizens participate in governance, ensuring that power is derived from the people. However, the historical struggle for suffrage reveals its deep entanglement with political movements and ideologies. For instance, the women’s suffrage movement in the early 20th century was not aligned with a single party but instead pressured existing parties to recognize their demands. This distinction highlights that suffrage is a tool for democratic engagement, not a partisan entity.

Analyzing the relationship between suffrage and democracy, it becomes clear that expanding voting rights strengthens democratic systems. When marginalized groups gain suffrage—whether women, racial minorities, or younger citizens—the electorate becomes more representative of the population. This inclusivity fosters legitimacy and trust in democratic institutions. For example, lowering the voting age to 16 in some countries has been proposed to engage youth in civic life earlier, though this remains a contentious issue. The key takeaway is that suffrage acts as a democratizing force, amplifying voices that were previously silenced.

To illustrate the practical link between suffrage and democracy, consider the role of voter registration drives and education campaigns. These initiatives, often led by non-partisan organizations, aim to maximize participation in elections. They demonstrate that suffrage is not merely a right but a responsibility that requires active facilitation. For instance, in the U.S., the Voting Rights Act of 1965 removed barriers to suffrage for African Americans, but ongoing efforts are still needed to combat voter suppression. Such actions underscore the dynamic interplay between suffrage and democratic health.

A comparative perspective reveals that democracies with higher suffrage rates tend to have more robust political systems. Countries like Sweden and Norway, with near-universal voter turnout, exhibit strong civic engagement and stable governance. Conversely, nations with restrictive voting laws often face challenges in maintaining democratic norms. This comparison suggests that safeguarding suffrage is essential for democracy’s survival. Practical steps include simplifying voter registration processes, ensuring accessible polling stations, and promoting civic education from a young age.

In conclusion, suffrage is not a political party but a vital link in the democratic chain. Its expansion and protection are critical for fostering inclusive and responsive governance. By understanding this relationship, individuals and policymakers can work toward strengthening democracies worldwide. The lesson is clear: suffrage is the lifeblood of democracy, and its health determines the vitality of the system it sustains.

The Erosion of Trust: What's Happened to Politics Today?

You may want to see also

Global Suffrage Variations

Suffrage, the right to vote, is not a political party but a fundamental principle of democracy, yet its implementation varies widely across the globe. These variations reflect cultural, historical, and political contexts, shaping how citizens engage with their governments. From age requirements to voting methods, the nuances of suffrage reveal much about a nation’s priorities and values. Understanding these differences is crucial for anyone seeking to compare democratic systems or advocate for electoral reform.

Consider the age of suffrage, a seemingly straightforward criterion that diverges sharply across countries. In Austria, 16-year-olds can vote in national elections, a move aimed at engaging younger citizens in civic life. Contrast this with the United States, where the voting age is 18, a standard adopted by most democracies. However, in some nations, such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, the voting age is tied to military service, complicating the universal application of this right. These variations highlight the tension between inclusivity and maturity as criteria for political participation.

Voting methods also illustrate global suffrage variations, with each system carrying distinct implications for accessibility and representation. Australia employs a preferential voting system, where voters rank candidates in order of preference, ensuring that elected officials have broader support. In contrast, the United States uses a first-past-the-post system, often criticized for favoring a two-party dominance. Meanwhile, Estonia stands out as a pioneer in digital suffrage, allowing citizens to vote online since 2005. These methods not only reflect technological readiness but also attitudes toward voter convenience and security.

The extent of suffrage rights further underscores global disparities. While many democracies grant universal suffrage to all citizens, exceptions persist. In some Gulf states, such as Kuwait, suffrage is restricted to certain groups, excluding women until as recently as 2005. Similarly, in countries like Brunei, suffrage does not exist in the context of direct elections, as the monarchy retains absolute power. These limitations reveal the ongoing struggle to achieve truly inclusive political participation worldwide.

Practical tips for navigating these variations include researching local electoral laws before advocating for change, as understanding the existing framework is essential for effective reform. For instance, if campaigning to lower the voting age, study successful cases like Austria’s to build a compelling argument. Additionally, when comparing voting systems, consider piloting hybrid models, such as combining online and in-person voting, to balance innovation with security. Finally, engage with international organizations like the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) to access resources and best practices in suffrage reform. By addressing these variations thoughtfully, advocates can contribute to more inclusive and equitable democratic systems globally.

Brutus 1 Critique: Political Parties and the Constitution Explored

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, suffrage is not a political party. Suffrage refers to the right to vote in political elections, not a specific political organization.

Suffrage is a fundamental right that enables citizens to participate in the political process, including voting for members of political parties. Political parties advocate for policies and candidates, but suffrage itself is a broader concept related to voting rights.

Yes, suffrage movements have historically been supported or opposed by various political parties, depending on their ideologies and goals. For example, the women's suffrage movement in the U.S. gained support from progressive and reform-oriented parties.

No, supporting suffrage means advocating for the right to vote, regardless of political affiliation. It is a non-partisan issue focused on democratic participation.

While there may be organizations or groups named in reference to suffrage, there are no major political parties specifically named "Suffrage Party." Suffrage is a principle, not a party identity.