The question of whether the USSR legalized other political parties is a critical aspect of understanding its political structure and history. Throughout its existence, the Soviet Union operated as a one-party state under the dominance of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), which held a monopoly on political power. While the Soviet Constitution nominally allowed for the existence of other political parties, in practice, opposition parties were either banned, suppressed, or co-opted, ensuring the CPSU's unchallenged control. This rigid system persisted until the late 1980s, when Mikhail Gorbachev's policies of *glasnost* (openness) and *perestroika* (restructuring) led to significant political reforms. In 1990, the CPSU's constitutional guarantee of power was abolished, paving the way for the legalization of multiple political parties. However, this shift was short-lived, as the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, marking the end of its centralized political system.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Legalization of Other Political Parties | The USSR did not legalize other political parties during its existence. |

| Political System | One-party state dominated by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). |

| Period of Existence | 1922–1991 |

| Constitution | The 1977 Soviet Constitution reinforced the CPSU's monopoly on power. |

| Opposition Parties | Officially banned; dissent was suppressed. |

| Perestroika Era | Under Gorbachev, limited political reforms began, but multi-party system was not fully legalized until the USSR's dissolution. |

| Dissolution of USSR | In 1991, the USSR collapsed, leading to the emergence of multi-party systems in successor states. |

| Legacy | The absence of legalized opposition parties remains a defining feature of Soviet political history. |

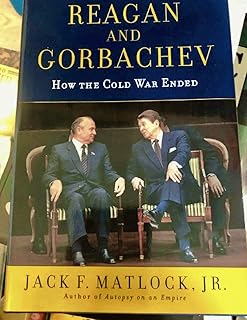

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Legal Reforms: Gorbachev's 1990 laws allowed multi-party system, ending CPSU monopoly

- Democratic Movements: Pro-democracy groups pushed for political pluralism in late 1980s

- CPSU Resistance: Communist Party resisted reforms, fearing loss of power

- Regional Parties: Ethnic regions formed parties, challenging central authority

- Post-USSR Impact: Legalization led to diverse parties in independent states post-1991

1990 Legal Reforms: Gorbachev's 1990 laws allowed multi-party system, ending CPSU monopoly

In 1990, Mikhail Gorbachev, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), introduced a series of landmark legal reforms that fundamentally transformed the Soviet political landscape. These reforms, enshrined in the 1990 laws, marked a pivotal moment in Soviet history by legalizing the existence of multiple political parties. This move effectively ended the decades-long monopoly of the CPSU, which had been the sole legal political party since the early years of the Soviet Union. The reforms were part of Gorbachev’s broader policy of *glasnost* (openness) and *perestroika* (restructuring), aimed at modernizing and democratizing the Soviet system. By allowing other political parties to operate legally, Gorbachev sought to foster political competition, encourage public participation, and address growing demands for reform from both within the Soviet Union and the international community.

The 1990 laws were a direct response to the mounting pressure for political liberalization across the Soviet republics. Gorbachev’s reforms included amendments to the Soviet Constitution, specifically Article 6, which had previously enshrined the CPSU’s leading role in the state and society. The removal of this article symbolized the end of the CPSU’s constitutional monopoly on power and opened the door for the formation of alternative political parties. These changes were formalized through the adoption of the Law on Public Associations in June 1990, which provided a legal framework for the creation and operation of political parties, movements, and organizations. This legislation ensured that political pluralism became a cornerstone of the Soviet political system, albeit during its final years.

The legalization of multiple political parties had immediate and far-reaching consequences. Opposition groups, which had previously operated underground or faced severe repression, could now organize openly. New parties emerged across the ideological spectrum, from nationalist movements in the republics to pro-democracy and liberal factions. For instance, the Democratic Russia Movement and the Russian Christian Democratic Party gained prominence, challenging the CPSU’s dominance in various regions. This proliferation of political parties reflected the diverse aspirations of the Soviet population and underscored the deepening fragmentation of the Soviet political landscape. However, the rapid transition to a multi-party system also exposed the weaknesses of the Soviet state, as the CPSU struggled to adapt to the new reality of political competition.

Gorbachev’s 1990 legal reforms were not without controversy or resistance. Hardliners within the CPSU viewed the legalization of other parties as a threat to the party’s authority and the integrity of the Soviet Union. This tension culminated in the failed August Coup of 1991, when conservative elements attempted to overthrow Gorbachev and reverse the reforms. Despite this backlash, the multi-party system had already taken root, and the coup accelerated the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The reforms of 1990, therefore, played a critical role in shaping the final chapter of Soviet history, paving the way for the emergence of independent states and the rise of new political orders across the former Soviet republics.

In retrospect, Gorbachev’s 1990 laws were a bold attempt to reconcile the Soviet system with the principles of democracy and political pluralism. By ending the CPSU’s monopoly and legalizing other political parties, these reforms signaled a profound shift in Soviet governance. While they did not prevent the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union, they left an enduring legacy by introducing the concept of political competition and citizen participation into the post-Soviet space. The 1990 legal reforms remain a testament to Gorbachev’s vision of a more open and inclusive Soviet society, even as they highlighted the challenges of transitioning from a one-party state to a multi-party democracy.

Dual Party Membership: Legal, Ethical, and Practical Considerations Explored

You may want to see also

Democratic Movements: Pro-democracy groups pushed for political pluralism in late 1980s

In the late 1980s, the Soviet Union witnessed a surge in pro-democracy movements that fervently advocated for political pluralism, challenging the long-standing monopoly of the Communist Party. These movements were fueled by Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of *glasnost* (openness) and *perestroika* (restructuring), which inadvertently created space for public discourse and criticism of the Soviet system. Pro-democracy groups, composed of intellectuals, workers, and students, began demanding the legalization of alternative political parties, arguing that genuine reform required competition and citizen representation beyond the Communist Party’s control. Their efforts marked a significant shift from passive dissent to organized political activism, as they sought to dismantle the one-party state and establish a multi-party system.

One of the most prominent pro-democracy groups was the Interregional Deputies' Group, formed in 1989 by elected representatives to the Congress of People's Deputies. This group, which included figures like Andrei Sakharov and Boris Yeltsin, pushed for radical political reforms, including the legalization of opposition parties. They argued that political pluralism was essential for addressing the Soviet Union’s economic and social crises, as it would allow for diverse solutions and greater accountability. Their activities were met with resistance from hardliners within the Communist Party, but they gained widespread public support, particularly in urban centers and among younger generations.

Another key movement was Democratic Russia, a coalition of pro-democracy organizations that emerged in 1989. This group organized mass rallies, petitions, and public campaigns to demand political liberalization, including the right to form and participate in alternative political parties. They also advocated for free elections, freedom of the press, and the rule of law, principles that directly challenged the Soviet authoritarian framework. Democratic Russia’s efforts were instrumental in pressuring the government to consider legal reforms that would allow for political competition, though progress was slow and uneven.

The push for political pluralism also manifested in the Baltic states, where pro-democracy movements like the Sąjūdis in Lithuania and the Popular Fronts in Estonia and Latvia demanded not only multi-party systems but also full independence from the Soviet Union. These movements organized massive demonstrations, such as the Baltic Way in 1989, where millions of people formed a human chain across the three republics to symbolize their unity and aspirations for freedom. Their demands for political pluralism were closely tied to their struggle for national self-determination, further intensifying pressure on the Soviet government.

By 1990, the Soviet government began to yield to these demands, albeit reluctantly. The March 1990 law formally ended the Communist Party’s constitutional monopoly on power, paving the way for the legalization of other political parties. However, this concession came too late to stabilize the Soviet Union, as the pro-democracy movements had already galvanized widespread support for fundamental change. The legalization of opposition parties marked a turning point, but it also accelerated the dissolution of the Soviet Union, as republics and political groups seized the opportunity to assert their autonomy and push for independence. The pro-democracy movements of the late 1980s thus played a pivotal role in reshaping the political landscape of the Soviet Union and its successor states.

Parliament Without Parties: Exploring Non-Partisan Governance Possibilities

You may want to see also

CPSU Resistance: Communist Party resisted reforms, fearing loss of power

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) played a central role in resisting political reforms that could have led to the legalization of other political parties in the USSR. Throughout its history, the CPSU maintained a monopoly on political power, enshrined in the Soviet Constitution, which declared the Party the "leading and guiding force of Soviet society." This monopoly was not merely a legal formality but a cornerstone of the Soviet system, ensuring the Party's control over all aspects of governance, economy, and ideology. Any attempt to introduce multi-party politics was seen as a direct threat to the CPSU's dominance and the stability of the regime.

The resistance to political reforms intensified during the late 1980s under Mikhail Gorbachev's leadership, particularly with his policies of *glasnost* (openness) and *perestroika* (restructuring). While these initiatives aimed to revitalize the Soviet system by introducing transparency and limited economic reforms, they inadvertently created space for public criticism and demands for greater political freedoms. The CPSU's conservative factions, deeply entrenched in the Party apparatus, viewed these developments with alarm. They feared that legalizing other political parties would dilute the CPSU's authority, expose it to competition, and potentially lead to its ouster from power. This fear was not unfounded, as the Party's legitimacy had already been eroded by decades of economic stagnation and growing public disillusionment.

The CPSU's resistance manifested in various ways, including internal opposition to Gorbachev's reforms, manipulation of Party structures to block changes, and the use of state institutions to suppress dissent. Conservative Party members argued that multi-party politics would lead to chaos, nationalism, and the disintegration of the Soviet Union. They pointed to the rise of nationalist movements in the republics as evidence of the dangers of liberalization. For instance, during the 19th Party Conference in 1988, many delegates expressed skepticism about further political reforms, emphasizing the need to preserve the CPSU's leading role. This resistance was not merely ideological but also rooted in self-interest, as many Party officials stood to lose their privileges and positions in a more open political system.

Despite Gorbachev's efforts to push for reforms, the CPSU's resistance slowed the pace of change and created a power struggle within the Party. The legalization of other political parties was only partially achieved in the late 1980s and early 1990s, as the Soviet Union began to unravel. The 1990 amendments to the Soviet Constitution formally ended the CPSU's monopoly on power, but by then, the Party's authority had been severely weakened. The resistance of the CPSU ultimately proved futile, as the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, marking the end of its political dominance and the beginning of a new era in Eastern Europe.

In retrospect, the CPSU's resistance to legalizing other political parties was a significant factor in the Soviet Union's inability to adapt to changing realities. The Party's fear of losing power led it to prioritize its own survival over the need for systemic reform, exacerbating the crises facing the USSR. This resistance highlights the challenges of implementing political liberalization in authoritarian systems, where ruling parties are often unwilling to relinquish control, even at the cost of their own demise. The CPSU's downfall serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of rigid political monopolies and the importance of inclusive political systems for long-term stability.

Political Parties and Data Privacy: Can They Purchase Your Information?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Regional Parties: Ethnic regions formed parties, challenging central authority

The Soviet Union, under the leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev, underwent significant political reforms in the late 1980s, including the introduction of *glasnost* (openness) and *perestroika* (restructuring). These reforms gradually opened up the political landscape, allowing for greater freedom of expression and organization. While the USSR did not fully legalize opposition parties during its existence, the loosening of central control enabled ethnic regions to form their own political parties, often as a means of asserting regional identity and challenging Moscow's authority. This phenomenon became particularly pronounced as the Soviet Union moved towards its dissolution in 1991.

Regional parties emerged as a response to decades of centralized rule and the suppression of ethnic identities. Ethnic republics within the USSR, such as the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania), Georgia, Armenia, and others, began to form political movements that prioritized local interests over those of the central government. These parties often advocated for greater autonomy, cultural preservation, and, in some cases, outright independence. For instance, the Popular Fronts in the Baltic states and the Round Table in Poland became powerful forces in mobilizing public support for self-determination, directly challenging the authority of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU).

The formation of these regional parties was facilitated by Gorbachev's policies, which inadvertently weakened the CPSU's grip on power. The 1990 legislation allowing the creation of political parties, though still restrictive, provided a legal framework for regional movements to organize. However, many of these parties operated outside the official system, leveraging grassroots support and international attention to advance their agendas. The central government's inability to suppress these movements highlighted the growing fragility of Soviet authority and the rise of nationalist sentiments across the republics.

The activities of regional parties often led to direct confrontations with Moscow. For example, the Baltic states declared their independence in 1990-1991, with their regional parties playing a pivotal role in organizing protests and resistance against Soviet attempts to reassert control. Similarly, in Georgia and Armenia, regional parties pushed for sovereignty, exacerbating tensions with the central government. These challenges to central authority underscored the shifting power dynamics within the USSR and accelerated its eventual collapse.

In conclusion, while the USSR did not fully legalize opposition parties, the reforms of the late 1980s created an environment in which regional parties could emerge and thrive. Ethnic regions capitalized on this opportunity to form political movements that challenged central authority, advocating for autonomy or independence. These developments were a critical factor in the disintegration of the Soviet Union, as they exposed the irreconcilable tensions between Moscow and the republics. The legacy of these regional parties continues to shape the political landscapes of the post-Soviet states, reflecting the enduring power of ethnic and national identities.

Vaccine Safety Views: How Political Party Affiliation Influences Public Trust

You may want to see also

Post-USSR Impact: Legalization led to diverse parties in independent states post-1991

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 marked a pivotal moment in the political landscape of the former USSR, as it led to the emergence of independent states with newfound opportunities for political pluralism. One of the most significant consequences of this event was the legalization of multiple political parties, which had been largely suppressed under the Soviet regime. Prior to its collapse, the USSR was dominated by the Communist Party, which held a monopoly on political power and did not tolerate opposition. However, the post-1991 era saw a dramatic shift, as newly independent states began to embrace multi-party systems, fostering a more diverse and competitive political environment.

In countries like Russia, Ukraine, and the Baltic states, the legalization of political parties led to the rapid formation of various groups representing different ideologies, from liberal democrats to nationalists and socialists. This diversity was a direct result of the newfound freedom to organize and participate in politics without fear of persecution. For instance, Russia witnessed the rise of parties such as the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) and Yabloko, which offered alternatives to the dominant Communist Party legacy. Similarly, Ukraine saw the emergence of parties like Rukh, which advocated for Ukrainian nationalism and independence, alongside pro-European and socialist movements. This proliferation of parties reflected the complex and varied aspirations of the populations in these newly independent states.

The impact of legalization extended beyond the mere existence of multiple parties; it also influenced the development of democratic institutions and political cultures. In many post-Soviet states, the introduction of multi-party systems was accompanied by efforts to establish free and fair elections, independent media, and civil society organizations. These developments were crucial in shaping the political trajectories of these nations, though the transition was often fraught with challenges, including corruption, political instability, and the lingering influence of authoritarian tendencies. Despite these obstacles, the legalization of diverse political parties laid the groundwork for more inclusive and representative governance structures.

Furthermore, the legalization of political parties had significant implications for regional and international relations. As post-Soviet states navigated their new independence, the ideologies and policies of their political parties often determined their alignment with global powers. For example, some parties advocated for closer ties with the West, while others sought to maintain or strengthen relationships with Russia. This political diversity contributed to a more complex and dynamic international landscape, as former Soviet republics pursued varying paths of development and integration. The ability of these states to foster diverse political parties thus played a critical role in shaping their identities and roles on the global stage.

In conclusion, the legalization of political parties post-1991 was a transformative development in the independent states of the former USSR, leading to a rich tapestry of political movements and ideologies. This shift not only reflected the aspirations of their populations but also influenced the establishment of democratic institutions and their engagement with the international community. While challenges persisted, the embrace of political pluralism marked a significant departure from the monolithic system of the Soviet era, paving the way for more diverse and representative political landscapes in the post-Soviet world.

Missouri Newspapers: Must They Declare Political Affiliations?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, the USSR did not legalize other political parties. It was a one-party state dominated by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), which held a monopoly on political power.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, under Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms (glasnost and perestroika), there were limited attempts to allow greater political pluralism. However, these efforts did not fully legalize opposition parties until the USSR's dissolution in 1991.

The USSR's constitution did not explicitly ban other parties but effectively ensured the CPSU's dominance. Article 6 of the 1977 Constitution enshrined the CPSU's leading role, making it nearly impossible for other parties to operate legally.