The United States Congress, comprising the House of Representatives and the Senate, is the sole body with the authority to enact legislation and declare war, as well as the power to confirm or reject presidential appointments. However, Congress does not have the power to appoint federal judges, including those for the Supreme Court; this power is reserved for the President. Pardoning people convicted of federal crimes is another power that does not belong to Congress, but to the President.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Appointment of federal judges | This power is vested exclusively in the President of the United States |

| Pardoning people convicted of federal crimes | This is not a power of Congress |

| Establishing post offices | This is not a power of Congress |

| Control of the budget | Congress holds the power to propose and approve the federal budget |

| Declaration of war | Congress has the exclusive authority to declare war |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Pardoning convicted federal criminals

The pardon power has its roots in ancient Jewish, Greek, and Roman legal principles and practices, as well as in English tradition, where the monarch could exercise the "royal prerogative of mercy" to provide alternatives to death sentences. In the United States, the pardon power was first established during the reign of King Henry VIII, when it was formally declared by Parliament as an exclusive right of the Crown.

A pardon is an executive order that grants clemency for a conviction. It may be granted "at any time" after the commission of a crime, and it is not restricted by any temporal constraints except that the crime must have already been committed. A pardon does not signify innocence or erase the record of the conviction, but it can restore various rights lost as a result of the conviction, such as firearm rights, the right to vote, and the ability to hold public office.

The President's power to pardon is considered nearly unlimited, with the exception of cases of impeachment. The President can pardon individuals before legal proceedings are taken, during their pendency, or after conviction and judgment. The pardon power extends to all federal criminal offenses and entails various forms of clemency, including commuting or postponing a sentence, remitting a fine or restitution, delaying the imposition of punishment, and providing amnesty to a group or class of individuals.

While Congress does not have the power to pardon convicted federal criminals, it can play a role in the process by providing advice and consent through the Senate's confirmation of presidential nominations for certain positions.

The Constitution's Guard Against Tyranny: A Historical Essay

You may want to see also

Appointing federal judges

The process of appointing federal judges is an example of the checks and balances established by the Constitution. While Congress cannot directly appoint federal judges, it can influence the process. Senators or members of the House of the President's political party may recommend names of potential nominees. Additionally, Congress creates legislation that must be enacted for court of appeals and district court judgeships to be established. The Judicial Conference, through its Judicial Resources Committee, also surveys the judgeship needs of the courts every other year and presents its recommendations to Congress.

The US Constitution states that federal judges hold their office during good behavior, which means they have a lifetime appointment, except under very limited circumstances. Federal judges can be removed from office only through impeachment by the House of Representatives and conviction by the Senate.

The appointment of federal judges can be influenced by the public opinion of the President and the shift in party control of the Senate. For example, a President with strong approval ratings may have an easier time achieving confirmation for a Justice or may have broader leeway in the type of Justice they nominate. On the other hand, an outgoing Justice's attributes can limit the options available to a President. For instance, replacing a pillar of the right or left may require a nominee that appeals to one political side more strongly.

Who Confirms Presidential Cabinet Picks?

You may want to see also

Approving presidential appointments

The US Congress plays a crucial role in approving presidential appointments, particularly through the Senate's confirmation of nominations. This process is outlined in the Appointments Clause of the US Constitution, which requires the President to nominate individuals for various positions with the "advice and consent" of the Senate.

The Appointments Clause distinguishes between two types of officers: principal officers and inferior officers. Principal officers, such as Supreme Court Justices and Ambassadors, must be appointed by the President with the confirmation of the Senate. On the other hand, inferior officers are those whose appointments Congress may place with the President, judiciary, or department heads. In other words, the President can appoint them without the Senate's approval.

The Presidential Appointment Efficiency and Streamlining Act of 2011 eliminated the requirement for Senate approval for 163 positions, allowing the President to appoint individuals to these positions independently. Examples of positions that previously required Senate confirmation but no longer do include the Administrator of the US Fire Administration and the Director of the Office of Counternarcotics Enforcement.

However, there are still numerous positions that require Senate confirmation. A 2012 study estimated that approximately 1200-1400 positions fall into this category. These positions are listed in the United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions (Plum Book), published after each US presidential election. Examples of positions requiring Senate confirmation include members of the Peace Corps National Advisory Council, the Broadcasting Board of Governors, and the Railroad Retirement Board.

In summary, while the President has the power to nominate individuals for various positions, the Senate's approval is often necessary, especially for principal officers. This system of checks and balances ensures accountability and a separation of powers between the executive and legislative branches of the US government.

Baserunning Glove Strike: Out or Safe?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Declaring war

The US Congress has the exclusive power to declare war, giving it control over military engagements and national defence. This power is enshrined in the US Constitution, which states that Congress has the power "to declare war, grant letters of marque and reprisal, and make rules concerning captures on land and water". This clause was intended to limit the president's power to take military action without Congress's approval.

In the early years of the US, Congress's approval was considered necessary for any significant use of force. For example, Congress issued a formal declaration of war for the War of 1812, and also approved lesser uses of force, such as the Quasi-War with France in 1798, conflicts with the Barbary States of Tripoli and Algiers, and conflicts with Native American tribes on the Western frontier.

However, in modern times, there have been several instances of presidents using military force without formal declarations of war or express consent from Congress. For example, President Truman ordered US troops into Korea in 1950, and President Obama authorised US participation in the 2011 bombing campaign in Libya without seeking Congressional approval, arguing that it did not rise to the level of "war" in the constitutional sense.

Congress has also authorised the use of force in more open-ended ways, such as when it approved the use of force to protect US interests and allies in Southeast Asia, which led to the Vietnam War. There is debate about how broadly to interpret these authorisations, and some presidents have claimed authorisation from indirect congressional actions, such as approval of military spending or assent by congressional leaders.

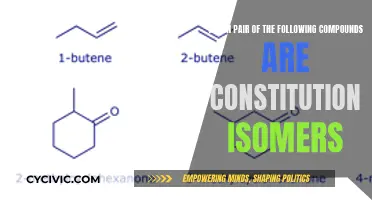

Constitutional Isomers of Methocarbamol: Exploring Chemical Alternatives

You may want to see also

Establishing post offices

The power to establish post offices and post roads is granted to Congress by Article I, Section 8, Clause 7 of the US Constitution. This clause gives Congress the authority to designate postal routes and construct postal facilities, as well as regulate the entire postal system of the country.

The postal system has been a critical component of the nation's infrastructure since its early days. The Post Office facilitated communication and commerce, with stagecoach trails being improved to serve as post roads, and mail contracts aiding the development of new transportation methods.

The interpretation of the postal clause has been a subject of debate, specifically regarding the word "establish". Some questioned whether it granted Congress the power to build new postal infrastructure or simply select existing infrastructure for postal use. Thomas Jefferson, in a letter to James Madison in 1796, pondered whether the power to establish post roads meant "that you shall make the roads, or only select from those already made".

In 1855, Justice John McLean stated that the power to establish post roads was generally accepted to mean the designation of roads for mail transportation, not the construction of new roads or bridges. This interpretation was solidified in the 1876 Kohl v. United States Supreme Court decision, which upheld the government's appropriation of land for a post office.

While the power to appoint federal judges is vested in the President, Congress does have a role in providing advice and consent through the Senate's confirmation process.

Years Since March 9: Time Flies So Fast

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Appointing federal judges.

Congress can influence the process by providing advice and consent, especially through the Senate's confirmation of the President's nominations.

Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution outlines the President's power to nominate judges.

Congress has the power to legislate, control the budget, declare war, and impeach.

Yes, if the President does not take any action on a bill within 10 days while Congress is in session, the bill becomes law.

![Acreage limitation provisions of reclamation law oversight hearings before the Subcommittee on Water and Power Resources of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs House of Repre [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81nNKsF6dYL._AC_UY218_.jpg)