Constitutional isomers, also known as structural isomers, are chemical compounds that have the same molecular formula but differ in the way their atoms are connected. This means that they have the same number of atoms but a different arrangement, resulting in distinct structures. For example, butane (C4H10) can have multiple structures due to the different ways its four carbons and ten hydrogens can be connected, making them constitutional isomers. When identifying constitutional isomers, it is important to consider the number of carbons and the degree of unsaturation (Hydrogen Deficiency Index). By following the IUPAC nomenclature rules, we can systematically name these compounds to avoid confusion. In this context, let's explore and identify which pairs of compounds among the given options are constitutional isomers.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Compounds that have the same molecular formula but exist as different structures |

| Other names | Structural isomers, tautomeric pairs |

| Examples | Ketone–enol, enamine–imine, butane, ethanol-drinking alcohol or dimethyl ether |

| Identification | Counting the number of carbons and the degree of unsaturation (Hydrogen Deficiency Index) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Constitutional isomers have the same chemical formula

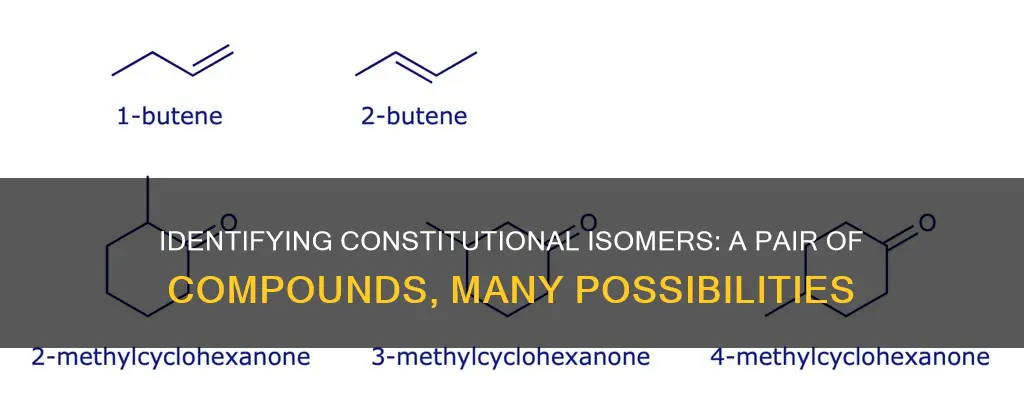

Constitutional isomers are compounds with the same molecular formula but different connectivity. They are also known as structural isomers. This means that constitutional isomers have the same number of atoms of each element, but these atoms are connected differently. For example, butane (C4H10) can have several structures where the four carbons and ten hydrogens are connected differently, making them constitutional isomers.

The concept of constitutional isomers is particularly relevant in organic chemistry, where there are virtually infinite ways to connect carbon atoms differently and create new molecules. For instance, ethanol (CH3CH2OH) and dimethyl ether (CH3OCH3) are constitutional isomers with the same molecular formula (C2H6O) but different atomic connectivity. In ethanol, the atomic connectivity is C—C—O, with the oxygen atom being part of an alcohol group. On the other hand, dimethyl ether has a C—O—C connectivity, forming an ether.

The distinction between constitutional isomers is crucial because their properties can differ significantly. For example, ethanol is the drinking alcohol, whereas dimethyl ether is a gas used as an aerosol propellant and starting fluid for internal combustion engines.

The identification and naming of constitutional isomers is essential to avoid confusion, especially in organic chemistry. A universal, systematic method for naming compounds was established by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) in 1892. This system ensures that each isomer has a unique name, preventing different names for the same compound, which was common in the past.

Baserunning Glove Strike: Out or Safe?

You may want to see also

Compounds with different structures are constitutional isomers

Compounds with different structures are called constitutional isomers. These compounds have the same molecular formula but differ in the way their atoms are linked or connected. For example, ethanol (C2H6O) and dimethyl ether (C2H6O) are constitutional isomers because they share the same molecular formula but differ in atomic connectivity: C—C—O in ethanol and C—O—C in dimethyl ether.

Constitutional isomers can be further classified into positional isomers and functional isomers. Positional isomers have the same functional groups but differ in their location within the molecule. For instance, 1-propanol and 2-propanol are positional isomers because they have a hydroxyl group on different carbon atoms. On the other hand, functional isomers have the same functional groups but differ in their location on the carbon skeleton. An example of functional isomers is A and B, which have the same functional group (OH) but located at different points on the carbon skeleton.

The easiest way to determine if molecules are constitutional isomers is to count the number of carbons and the degree of unsaturation (Hydrogen Deficiency Index or HDI). If the molecules have the same number of atoms and the same HDI, they are likely constitutional isomers. However, for larger molecules, it is necessary to name the molecules according to the IUPAC nomenclature rules to be certain.

Constitutional isomers can also be structural isomers, or tautomers, that can readily interconvert with each other through a reaction known as tautomerization, which involves relocating a proton. An example of a common tautomeric pair is ketone-enol.

Understanding California's Hostile Work Environment Laws

You may want to see also

Stereoisomers are different from constitutional isomers

Isomers are two or more molecules that share the same molecular formula but differ in structure. They can be divided into two categories: constitutional isomers and stereoisomers.

Constitutional isomers, also known as structural isomers, are compounds that have the same molecular formula but differ in the way their atoms are connected. These isomers have different IUPAC names, which are assigned according to the rules set by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC). For example, 2-methylpropane (C4H10) and butane (C4H10) are constitutional isomers of each other, as they share the same molecular formula but differ in the arrangement of their atoms.

On the other hand, stereoisomers are isomers that have the same molecular formula and connectivity but differ in their three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in space. They can be further classified into enantiomers and diastereomers. Enantiomers are stereoisomers that are mirror images of each other and are non-superimposable. A pair of enantiomers exhibits optical activity, meaning they rotate the plane of polarized light in opposite directions. Diastereomers, on the other hand, are stereoisomers that are not mirror images of each other and have different chemical and physical properties.

The key difference between constitutional isomers and stereoisomers lies in their molecular structure and connectivity. Constitutional isomers have the same molecular formula but differ in the way their atoms are connected, resulting in distinct IUPAC names. Stereoisomers, on the other hand, have the same molecular formula and connectivity but differ in the spatial arrangement of their atoms. This means that stereoisomers have the same constitutional arrangement of atoms but differ in how those atoms are oriented in three-dimensional space.

It is important to note that a molecule can be classified as one type of isomer or the other, but not both simultaneously. For example, the amino acid (S)-alanine and its enantiomer (R)-alanine are a pair of stereoisomers, as they are mirror images of each other. However, they cannot be constitutional isomers because they do not have the same molecular formula.

Understanding the Constitution: A Quick Read or a Lifetime Study?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Tautomers are structural isomers

Tautomers are distinct chemical species that can be distinguished by their differing atomic connectivities, molecular geometries, and physicochemical and spectroscopic properties. The existence of tautomers can be detected spectroscopically, as all the tautomeric forms may give rise to different spectral features. The most common form of tautomerism involves a hydrogen atom changing places with a double bond. The chemical reaction interconverting the two isomers is called tautomerization, or tautomerism, also known as desmotropism. This conversion commonly results from the relocation of a hydrogen atom within the compound.

Tautomers should not be confused with depictions of "contributing structures" in chemical resonance. While tautomers are distinct chemical species, resonance forms are merely alternative Lewis structures of a single chemical species, whose true structure is a quantum superposition. Ring-chain tautomers occur when the movement of the proton is accompanied by a change from an open structure to a ring, such as the open chain and cyclic hemiacetal of many sugars. Another example is the equilibrium between imines (also known as Schiff bases) and enamines, which are the nitrogen equivalents of enols.

Valence tautomerism is a type of tautomerism in which single and/or double bonds are rapidly formed and ruptured, without migration of atoms or groups. It is distinct from prototropic tautomerism, and involves processes with rapid reorganisation of bonding electrons. Prototropic tautomerism may be considered a subset of acid-base behaviour.

The Constitution's Guard Against Tyranny: A Historical Essay

You may want to see also

Chirality and enantiomers

The concept of chirality and enantiomers is an important topic within the field of chemistry, particularly in the study of isomers. Chirality refers to the property of a molecule being asymmetrical, meaning it is non-superposable on its mirror image. This is similar to how our left and right hands are mirror images of each other but cannot be superimposed. In the context of isomers, chirality plays a crucial role in distinguishing between different types of stereoisomers, which include enantiomers and diastereomers.

Enantiomers are a type of stereoisomer that are like non-superimposable mirror images of each other. They have the same molecular formula and connectivity but differ in how their atoms are arranged in space. A molecule with a single chiral centre, or asymmetric carbon, will exist as a pair of enantiomers. These enantiomers have identical physical properties, except for their ability to rotate plane-polarised light, also known as optical rotation. This property is often used to distinguish between enantiomers.

The concept of chirality is essential in understanding enantiomers because it is the presence of a chiral centre that gives rise to enantiomers. A chiral centre, or asymmetric centre, is a carbon atom bonded to four different groups. There are only two ways to arrange four different substituents around a tetrahedral carbon, resulting in a pair of enantiomers. This was first observed by Louis Pasteur when he discovered that racemic acid, now known as tartaric acid, was actually a mixture of two mirror-image forms of tartaric acid.

Enantiomers can be challenging to separate due to their identical solubilities, melting points, and other physical properties. However, they can exhibit different biological activities, making them important in fields like pharmacology, where one enantiomer may be the active ingredient in a drug while the other may be inactive or even harmful. The understanding of chirality and enantiomers has significant implications in various scientific disciplines, including chemistry, biology, and pharmacology.

Workplace Harassment: Abusive Conduct and the Law

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Constitutional isomers are compounds that have the same molecular formula but differ in the way their atoms are connected. They are also known as structural isomers.

To determine if a pair of compounds are constitutional isomers, you can start by counting the number of carbons and the degree of unsaturation (Hydrogen Deficiency Index). If the compounds have the same number of atoms and the same HDI, they may be constitutional isomers. For more complex molecules, it is important to name the molecules according to IUPAC nomenclature rules to be certain.

An example of a pair of compounds that are constitutional isomers is butane (C4H10). Butane can have different structures, or isomers, where the four carbons and ten hydrogens are connected differently.

Constitutional isomers have the same molecular formula but differ in the connectivity between atoms. Stereoisomers, on the other hand, have the same order of bonding but differ in the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms.