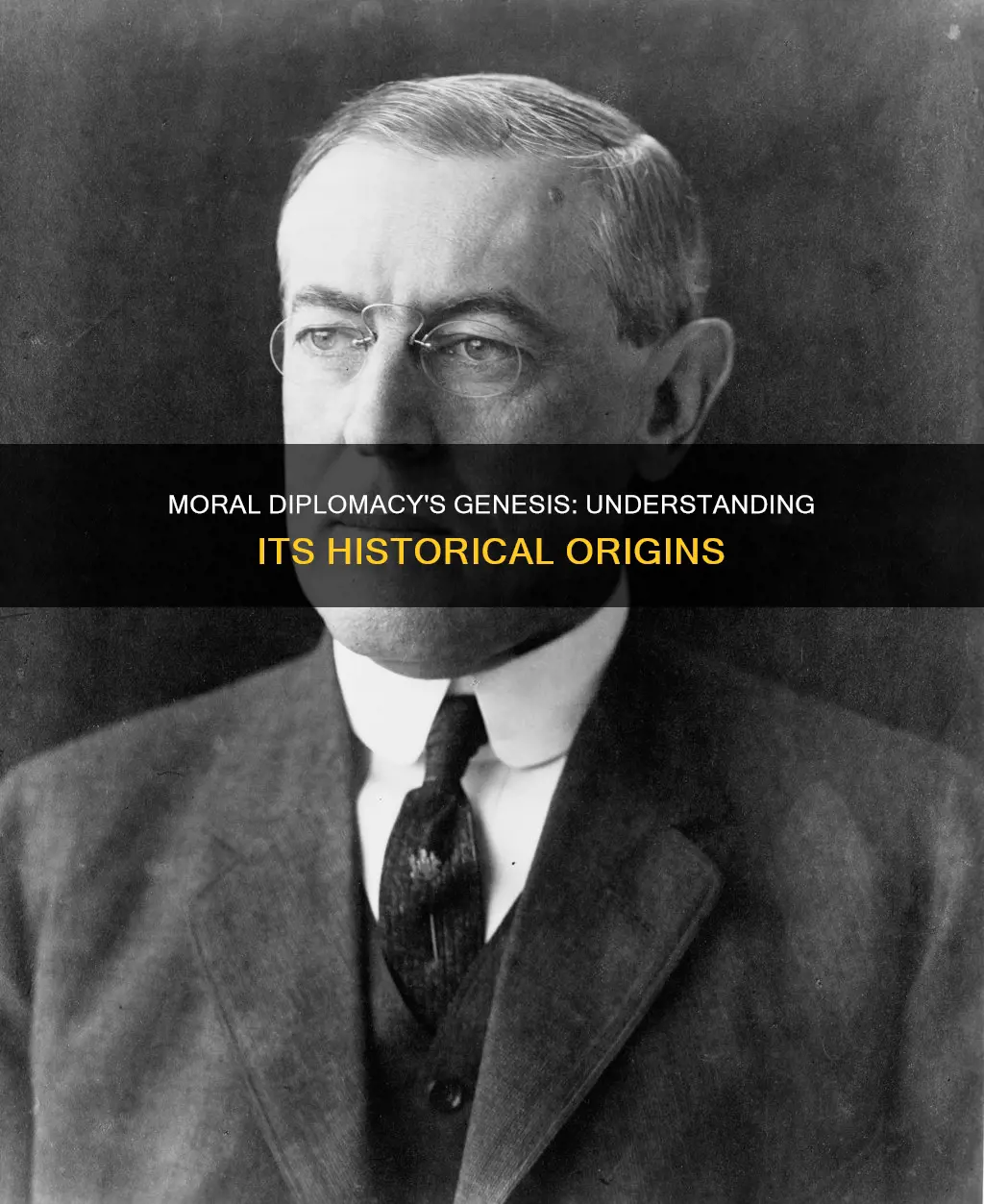

Moral diplomacy was a foreign policy approach introduced by US President Woodrow Wilson. Wilson's moral diplomacy, which began in 1913, was based on the principles of democracy, self-determination, and morality. It marked a shift from the imperialist policies of his predecessors, aiming to curb the growth of imperialism and spread democracy, particularly in Latin America. Wilson believed that the US had a duty to promote democratic values and ethics in international relations, even if it meant applying military, economic, and political pressure on nations that did not align with these values.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Originator | Woodrow Wilson |

| Objective | To curb the growth of imperialism and spread democracy |

| Core principle | Self-determination |

| Alternative to | Imperialist policy |

| Application | Applied military, economic, and political pressure to territories and governments whose values did not align with those of Wilson's America |

| Focus | Morality and ethical considerations |

| Examples | Interventions in Mexico, Latin America, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Cuba, and Panama |

Explore related products

$14.95 $14.95

What You'll Learn

Woodrow Wilson's foreign policy

Wilson's foreign policy was also based on his idea of "Wilsonianism", which emphasised the right of individual nations to self-determination. This was a shift from isolationism to internationalism, with Wilson believing that nations needed to forge international organisations to solidify their mutual goal and place even greater pressure on non-democratic entities. Wilson's 14 points, outlined in a speech to Congress in 1918, called for a "new diplomacy" consisting of "open covenants openly arrived at". He wanted to dismantle the imperial order by opening up colonial holdings to eventual self-rule and all European sections of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires to immediate independence. He also proposed a general disarmament after the war, with the Germans and Austrians giving up their armed forces first.

Wilson's foreign policy was also marked by his intervention in the affairs of other countries, specifically Latin America. He frequently stated that he wanted to spread democracy and believed that America had a duty to do so. This was known as "moral diplomacy", which was based on economic power rather than the economic support of his predecessor's "dollar diplomacy". Wilson's moral diplomacy was used in his relationships with various governments, most notably in Mexico and Latin America. In 1914, Wilson refused to recognise the authoritarian government of Victoriano Huerta in Mexico, instead encouraging anti-Huerta forces in northern Mexico led by Venustiano Carranza. He also used the arrest of several American sailors in Tampico in 1914 to justify ordering the US Navy to occupy the port city of Veracruz, which greatly weakened Huerta's control. Wilson also sent troops to Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Cuba, ostensibly to restore order but failed to create the democratic states that were the stated objective.

Celebrities' Political Influence: Campaigns and Voter Decisions

You may want to see also

American exceptionalism

Woodrow Wilson's moral diplomacy was based on the notion of American exceptionalism, which holds that the United States has a unique mission to spread liberty and democracy worldwide. This idea can be traced back to Alexis de Tocqueville, who first described the United States as "exceptional" in the 1830s. Wilson's foreign policy, particularly towards Latin America, was driven by this belief.

Wilson's moral diplomacy represented a departure from the dollar diplomacy of his predecessor, William Howard Taft, which prioritised economic support to strengthen bilateral ties. In contrast, Wilson's approach emphasised the use of American economic power, military force, and political pressure to spread democratic values and self-determination. He frequently intervened in Latin American countries, including Mexico, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and Panama, to promote his vision of democracy. Wilson saw moral diplomacy as a way to curb imperialism and empower developing nations to become self-sustaining and democratic.

The core principle of Wilson's moral diplomacy was the belief in the moral right of people to choose their form of government and leaders through democratic elections. This stood in contrast to the imperialist policies of his predecessors, which focused on extending American power and control. Wilson's vision, outlined in his Fourteen Points speech in 1918, called for a new diplomacy based on open covenants, self-determination, and international cooperation. He believed that spreading democracy required nations to work together and form international organisations to solidify their mutual goals.

Wilson's moral diplomacy reflected his determination to base foreign policy on moral principles rather than materialism. He encouraged the country to look beyond its economic interests and define its foreign policy in terms of ideals, morality, and the spread of democracy. This shift from isolationism to internationalism eventually led to the United States becoming a global actor in international affairs, with a belief in American morality at its core. Wilson's ideas about moral diplomacy were influenced by his belief in American exceptionalism and the notion that the United States had a unique role to play in spreading liberty and democracy worldwide.

Unilateral Diplomacy: Navigating the Complex World Alone

You may want to see also

Latin America

Woodrow Wilson's moral diplomacy in Latin America was driven by his belief in American exceptionalism and the idea that the United States had a moral duty to spread democracy and ensure peace and freedom in the region. However, critics argue that it ultimately served to protect American economic and political hegemony.

In Latin America, Wilson frequently intervened in the internal affairs of various countries, including Mexico, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, Panama, and Cuba. He justified these interventions under the principles of moral diplomacy, aiming to curb the growth of imperialism and promote democracy. For example, in Mexico, Wilson refused to recognize Victoriano Huerta as the country's leader in 1913 due to his illegal seizure of power and supported Venustiano Carranza, who became president with Wilson's military support. Wilson also sent troops to Mexico in 1916 to pursue Pancho Villa, who had killed several Americans, but this intervention failed to capture Villa and escalated tensions.

Haiti was another significant focus of Wilson's moral diplomacy. He enacted an armed occupation of the country in 1915 due to concerns about high levels of European investment threatening American hegemony in the Caribbean and the potential for Germany to gain influence. Wilson's administration covertly obtained financial and administrative control of Haiti while supporting their chosen Haitian leader. Similarly, in the Dominican Republic, Wilson intervened in 1916, citing political and fiscal unrest, and oversaw elections while maintaining a military presence until 1924.

In Cuba, Wilson continued the American occupation, ostensibly to bring peace and stability, but his actions centered around protecting sugar plantations monopolized by US companies. Additionally, Wilson kept US troops in Nicaragua throughout his administration and used them to influence the selection of the country's president.

Wilson's moral diplomacy in Latin America was characterized by his insistence on democratic governments and his willingness to use military force to achieve his objectives. While he claimed to respect the self-determination of Latin American nations, his interventions often undermined their autonomy and created permanent hostility between the United States and the region.

Public Diplomacy: Propaganda in Disguise?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Opposition to imperialism

Woodrow Wilson's moral diplomacy was a direct opposition to the imperialism of his predecessors, Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, who upheld a strictly nationalist foreign policy, seeking to expand the American empire. Wilson's moral diplomacy replaced Taft's dollar diplomacy, which was based on economic support to improve bilateral ties between nations.

Wilson's approach was based on the principle of self-determination, believing that people had the moral right to choose their form of government and leaders through democratic elections. This was a shift from the previous policy of intervention and action based solely on economic expansion. Wilson's moral diplomacy was intended to empower developing nations to become self-sustaining and democratic, and to intervene in European imperialist efforts.

However, Wilson's insistence on democracy undermined the promise of self-determination for Latin American states. While he declared that the United States hoped to "cultivate the friendship and deserve the confidence" of these states, his insistence that their governments be democratic went against the Latin American states' desire to be free to conduct their own affairs without American interference. This contradiction was evident in Wilson's interventions in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Panama, and Nicaragua, where he sent American troops to restore order and select leaders, justifying his actions through his belief in American exceptionalism.

Wilson's moral diplomacy also clashed with the interests of Americans with economic stakes in Mexico, where he refused to recognize Victoriano Huerta's government despite it being supported by most Americans and many foreign powers. This refusal was due to Huerta's illegal seizure of power, demonstrating Wilson's commitment to moral principles over materialism in his foreign policy.

Despite Wilson's intentions to curb imperialism and spread democracy, his actions were often viewed as a prime example of American exceptionalism, where American ideology, policy, and institutions are believed to be superior and universally applicable, even by force. Critics argue that Wilson's interventions in other countries, particularly in Latin America, were a form of aggressive moral diplomacy that led to military occupation and economic control, failing to create the democratic states they aimed for.

Donating Stock to Political Campaigns: Is It Possible?

You may want to see also

Self-determination

Woodrow Wilson's moral diplomacy was driven by the principle of self-determination, which refers to the moral right of people to choose their form of government and leaders through democratic elections. Wilson's vision of self-determination was a departure from the imperialist policies of his predecessors, which focused on expanding American power and dominion. Instead, Wilson's approach sought to empower developing nations to become self-sustaining and democratic, believing that moral diplomacy would curb the growth of imperialism.

In his 1913 statement, Wilson expressed his intention to intervene in the affairs of Latin American countries, stating, "I am going to teach the South American republics to elect good men." This belief in the need for democratic governments and the self-determination of peoples and states was a core aspect of Wilson's foreign policy. He frequently intervened in Latin America and countries like Mexico, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and Panama to promote democracy and moral values.

Wilson's Fourteen Points, outlined in a speech to Congress on January 18, 1918, exemplified his commitment to self-determination. The plan included creating openness in diplomacy, ending secret treaties, and fostering the self-determination of all nations. He called for a "new diplomacy" of "open covenants openly arrived at," aiming to dismantle the imperial order and promote eventual self-rule in colonial holdings. Wilson's vision extended to European sections of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires, which he proposed should gain immediate independence.

However, Wilson's insistence on democratic governments in Latin America undermined the promise of self-determination for those states. His interventions in Haiti and the Dominican Republic in the form of military occupations failed to establish the democratic states he envisioned. Wilson's actions in Latin America have been described as old-fashioned imperialism, as he exerted military, economic, and political pressure on territories whose values did not align with those of the United States.

Despite the contradictions and challenges of Wilson's moral diplomacy, his ideas had a lasting impact. They laid the groundwork for democratic nations to collaborate internationally and solidified the US as a global actor in international affairs, with a belief in American morality and the spread of democracy at its core.

John Quincy Adams' Diplomacy: A Legacy of Peace

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Moral diplomacy began during the presidency of Woodrow Wilson, from 1913 to 1921.

Moral diplomacy was a type of foreign policy based on moral principles, democracy, and the self-determination of nations. It was a departure from the imperialist policies of Wilson's predecessors, which were driven by economic expansion.

The key principles of moral diplomacy were democracy and the self-determination of nations. Wilson believed that the United States had a duty to spread democracy and ensure that governments were based on the consent of the governed.

Wilson promoted moral diplomacy through his Fourteen Points plan, which called for a new diplomacy of open covenants, free trade, and an end to secret treaties. He also used military, economic, and political pressure on territories that did not align with American values.

Wilson's moral diplomacy had mixed results. While it laid the groundwork for the United States to become a global actor in international affairs, it also led to interventions in Latin America and military occupations in Haiti and the Dominican Republic that failed to create democratic states.