Before Abraham Lincoln's presidency, the American political landscape was dominated by several key parties that reflected the ideological and regional divisions of the time. The Democratic Party, which had been a major force since the 1820s, advocated for states' rights, limited federal government, and the expansion of slavery. In contrast, the Whig Party, prominent in the 1830s and 1840s, supported industrialization, internal improvements, and a stronger federal role in economic development, though it eventually collapsed due to internal disagreements over slavery. The Free Soil Party, formed in the late 1840s, opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories, attracting anti-slavery Democrats and Whigs. By the 1850s, the Republican Party emerged as a new force, uniting anti-slavery activists and former Whigs to challenge the Democrats' dominance. These parties, along with smaller factions like the Know-Nothing Party, shaped the tumultuous political environment leading up to Lincoln's election in 1860.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Major Political Parties | Democratic Party, Whig Party, Republican Party (emerging), Know-Nothing Party (American Party) |

| Time Period | Pre-1861 (before Lincoln's presidency began in 1861) |

| Dominant Party | Democratic Party (held significant power in the South and parts of the North) |

| Key Issues | Slavery, states' rights, tariffs, westward expansion |

| Whig Party Focus | Economic modernization, internal improvements, national bank |

| Democratic Party Focus | States' rights, limited federal government, expansion of slavery |

| Republican Party Emergence | Formed in the 1850s, opposed slavery expansion, gained support in the North |

| Know-Nothing Party Focus | Anti-immigration, anti-Catholic sentiment, nativism |

| Sectional Divide | North vs. South on slavery and economic policies |

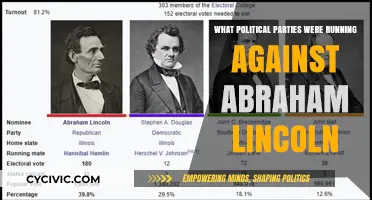

| Notable Figures | Stephen A. Douglas (Democrat), Henry Clay (Whig), William Seward (Republican) |

| Decline of Whig Party | Collapsed in the 1850s due to internal divisions over slavery |

| Impact on Lincoln | Lincoln emerged as the first Republican president in 1860 |

Explore related products

$1.99 $24.95

What You'll Learn

- Whig Party: Supported protective tariffs, internal improvements, and national banking; dominant in the 1830s-1850s

- Democratic Party: Advocated states' rights, limited federal government, and expansionism; major rival to Whigs

- Free Soil Party: Opposed slavery expansion into new territories; precursor to the Republican Party

- Know-Nothing Party: Nativist movement; focused on restricting immigration and political influence of Catholics

- Constitutional Union Party: Formed in 1860 to preserve the Union without addressing slavery

Whig Party: Supported protective tariffs, internal improvements, and national banking; dominant in the 1830s-1850s

The Whig Party, a dominant force in American politics from the 1830s to the 1850s, was a coalition of diverse interests united by a common vision of economic modernization. At its core, the party championed three key policies: protective tariffs, internal improvements, and national banking. These initiatives were not mere political talking points but strategic tools to foster industrial growth, infrastructure development, and financial stability. By imposing tariffs on imported goods, Whigs aimed to shield American manufacturers from foreign competition, ensuring domestic industries could thrive. This protectionist approach was particularly appealing to the industrial North, where factories and mills were rapidly expanding.

Consider the impact of internal improvements, another Whig priority. This term encompassed federally funded projects like roads, canals, and railroads, which were essential for connecting the vast American landscape. For instance, the National Road, a Whig-supported project, stretched from Maryland to Illinois, facilitating trade and migration. Such investments not only strengthened the economy but also symbolized the Whigs' commitment to a unified, interconnected nation. However, these ambitious projects often sparked debates over states' rights and federal authority, revealing the complexities of Whig policy implementation.

National banking, the third pillar of Whig economic policy, sought to create a stable financial system. Whigs advocated for a centralized banking structure, culminating in the establishment of the Second Bank of the United States. This institution aimed to regulate currency, manage inflation, and provide a secure foundation for economic transactions. Yet, it also became a lightning rod for controversy, with critics like President Andrew Jackson arguing it favored the wealthy elite. Despite this, the Whigs' push for national banking reflected their belief in a strong federal role in economic affairs, a stance that set them apart from their political rivals.

Analyzing the Whigs' dominance reveals a party adept at appealing to both economic and national interests. Their policies were tailored to address the needs of a rapidly industrializing nation, yet they also carried inherent tensions. Protective tariffs, while beneficial to Northern manufacturers, alienated Southern agriculturalists who relied on international trade. Internal improvements, though transformative, raised questions about the extent of federal power. These contradictions ultimately contributed to the party's decline as regional divisions deepened in the 1850s. Still, the Whigs' legacy endures in the infrastructure and economic institutions they helped establish, shaping the course of American development long after their dissolution.

For those studying political history or economic policy, the Whig Party offers a compelling case study in balancing national ambition with regional realities. Their focus on protective tariffs, internal improvements, and national banking provides a blueprint for understanding how political parties can drive economic transformation. However, it also serves as a cautionary tale about the challenges of maintaining unity in a diverse nation. By examining the Whigs' rise and fall, we gain insights into the complexities of policy-making and the enduring tensions between federal authority and local interests.

Equality's Rise: Political Parties Shaping Inclusive Democracy and Representation

You may want to see also

Democratic Party: Advocated states' rights, limited federal government, and expansionism; major rival to Whigs

The Democratic Party, a dominant force in American politics before Lincoln's presidency, championed a distinct ideology centered on states' rights, limited federal government, and expansionism. This platform positioned them as the primary rival to the Whig Party, creating a dynamic political landscape that shaped the nation's trajectory.

A Philosophy of Decentralization: At its core, the Democratic Party believed in a weak central government, arguing that power should reside primarily with individual states. This philosophy, rooted in Jeffersonian ideals, emphasized local control and autonomy. Democrats feared a strong federal government could lead to tyranny and infringe upon individual liberties. This commitment to states' rights extended to various issues, including economic policy, where Democrats favored minimal federal intervention in commerce and industry.

Expansionist Ambitions: Democrats were fervent advocates of westward expansion, a policy known as "Manifest Destiny." They believed it was America's destiny to stretch from coast to coast, and this ideology fueled their support for the annexation of Texas, the Oregon Territory, and the Mexican-American War. This expansionist zeal was not merely about territorial growth; it was intertwined with their belief in individual opportunity and the spread of democratic ideals.

Rivalry with the Whigs: The Whigs, in contrast, favored a more active federal government, particularly in promoting economic development through infrastructure projects and a national bank. This fundamental difference created a stark ideological divide. Whigs viewed Democratic policies as hindering national progress, while Democrats saw Whig proposals as overreaching and threatening to state sovereignty. This rivalry played out in numerous elections, with the two parties vying for control of Congress and the presidency.

Legacy and Impact: The Democratic Party's emphasis on states' rights and limited government had profound consequences. It contributed to the growing sectional tensions between the North and South, as Southern Democrats increasingly saw federal power as a threat to slavery. This ideological divide ultimately played a significant role in the lead-up to the Civil War. Understanding the Democratic Party's pre-Lincoln platform is crucial for comprehending the political and social forces that shaped the United States during this pivotal era.

Martha MacCallum's Political Affiliation: Unraveling Her Party Ties

You may want to see also

Free Soil Party: Opposed slavery expansion into new territories; precursor to the Republican Party

The Free Soil Party emerged in the 1840s as a direct response to the contentious issue of slavery’s expansion into newly acquired territories. Formed in 1848, the party coalesced around the slogan "Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Labor, and Free Men," reflecting its core opposition to the spread of slavery into lands like the Mexican Cession. Its members, often referred to as "Free Soilers," were a diverse coalition of anti-slavery Democrats, Whigs, and abolitionists who prioritized preventing slavery’s westward extension over its immediate abolition in the South. This pragmatic stance distinguished them from more radical abolitionist groups, making them a pivotal force in the pre-Civil War political landscape.

At its heart, the Free Soil Party’s ideology was rooted in economic and moral arguments against slavery. They believed that allowing slavery into new territories would undermine the opportunities for free white laborers, who would be forced to compete with enslaved workers. This perspective resonated with Northern voters, particularly farmers and working-class citizens, who saw slavery as a threat to their economic prospects. The party’s 1848 presidential candidate, former President Martin Van Buren, captured just 10% of the popular vote, but their influence extended far beyond electoral success. By framing the slavery debate in terms of economic fairness, they laid the groundwork for a broader anti-slavery coalition.

The Free Soil Party’s impact was most evident in its role as a precursor to the Republican Party. After the passage of the Compromise of 1850, which allowed for the possibility of slavery in new territories, many Free Soilers grew disillusioned with the existing political system. This frustration, combined with the growing polarization over slavery, led to the formation of the Republican Party in 1854. Key figures from the Free Soil Party, such as Salmon P. Chase and Charles Sumner, became prominent Republicans, carrying forward the Free Soil principles of opposing slavery’s expansion. Without the Free Soil Party’s initial efforts to unite anti-slavery forces, the Republican Party might not have emerged as a cohesive and powerful political entity.

To understand the Free Soil Party’s legacy, consider its practical contributions to the anti-slavery movement. They were among the first to successfully mobilize voters around a single issue—preventing slavery’s spread—rather than advocating for its immediate abolition. This strategic focus allowed them to appeal to a broader audience, including those who were not staunch abolitionists but opposed slavery on economic or moral grounds. Their approach demonstrated the power of incrementalism in political change, a lesson that would later inform the Republican Party’s strategy in the lead-up to the Civil War.

In retrospect, the Free Soil Party’s significance lies in its ability to bridge the gap between moral opposition to slavery and practical political action. By focusing on the issue of slavery’s expansion, they created a platform that could unite diverse factions against a common threat. Their legacy is not just in their immediate achievements but in their role as a catalyst for the Republican Party, which would eventually elect Abraham Lincoln and steer the nation toward the end of slavery. The Free Soil Party’s story is a reminder that even small, focused movements can have profound and lasting impacts on history.

Exploring the Diverse Political Parties in the United States

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Know-Nothing Party: Nativist movement; focused on restricting immigration and political influence of Catholics

The Know-Nothing Party, formally known as the American Party, emerged in the 1850s as a potent force in American politics, capitalizing on widespread anxieties about immigration and the growing influence of Catholics in public life. Its rise was a stark reflection of the nativist sentiment that gripped the nation during this period, as native-born Protestants feared their cultural and political dominance was under threat. The party’s platform was clear: restrict immigration, limit the political power of Catholics, and preserve what they saw as the nation’s Protestant heritage. This movement was not merely a fringe group but a significant political force, winning control of state legislatures and even the mayor’s office in major cities like Boston and Philadelphia.

At its core, the Know-Nothing Party’s strategy was twofold: first, to impose a 21-year residency requirement for citizenship, effectively delaying immigrants’ ability to vote, and second, to prohibit Catholics from holding public office. These measures were rooted in the belief that immigrants, particularly Irish Catholics, were loyal to the Pope rather than the United States and posed a threat to American democracy. The party’s secrecy—members were instructed to say, “I know nothing” when asked about its activities—only added to its mystique and appeal among those who felt disenfranchised by the rapid social changes of the era.

To understand the Know-Nothing Party’s appeal, consider the context of the 1850s. Immigration from Ireland and Germany had surged due to the Great Famine and political unrest in Europe, leading to a demographic shift in American cities. Native-born workers feared competition for jobs, while Protestant leaders worried about the spread of Catholicism. The party’s nativist rhetoric resonated with those who felt their way of life was under siege. For instance, in Massachusetts, the Know-Nothings gained control of the state government in 1854, passing laws that restricted the rights of immigrants and sought to curb Catholic influence in schools.

However, the Know-Nothing Party’s success was short-lived. Its inability to address broader economic and sectional issues, such as slavery, limited its appeal beyond nativist concerns. By the late 1850s, the party had largely dissolved, as its members either returned to the Whigs or joined the newly formed Republican Party. Yet, its legacy endures as a cautionary tale about the dangers of xenophobia and religious intolerance in politics. The party’s rise and fall underscore the importance of addressing the root causes of societal fears rather than exploiting them for political gain.

In practical terms, the Know-Nothing Party’s policies offer a stark reminder of the consequences of exclusionary politics. While concerns about immigration and cultural change are not inherently invalid, addressing them through discriminatory measures only deepens divisions. Today, as debates over immigration and national identity continue, the Know-Nothing Party serves as a historical example of how fear-based movements can gain traction but ultimately fail to provide lasting solutions. Its story is a call to approach these issues with empathy, inclusivity, and a commitment to the principles of equality and justice.

Texas County Political Parties: Tax-Exempt Status Explained

You may want to see also

Constitutional Union Party: Formed in 1860 to preserve the Union without addressing slavery

The Constitutional Union Party emerged in 1860 as a desperate attempt to bridge the widening chasm between the North and South. Unlike other parties of the era, it deliberately avoided the contentious issue of slavery, focusing instead on preserving the Union at all costs. This strategy, while seemingly pragmatic, reflected a profound unwillingness to confront the moral and political crisis tearing the nation apart. The party's platform was a testament to the belief that compromise, even at the expense of principle, could stave off secession. However, history would prove this approach tragically insufficient.

To understand the Constitutional Union Party, consider its formation as a political Hail Mary. The Democratic Party had fractured over slavery, and the Republican Party's rise threatened Southern interests. The Constitutional Union Party, led by figures like John Bell, sought to appeal to moderates in border states who feared the consequences of secession but were unwilling to endorse abolition. Their slogan, "The Union as it is, the Constitution as it is," encapsulated this stance. Yet, this refusal to address slavery was both its appeal and its fatal flaw. It offered a temporary bandage but no cure for the nation's deepest wound.

A comparative analysis reveals the party's unique position. While the Republicans under Lincoln advocated for halting the expansion of slavery, and the Southern Democrats pushed for its protection, the Constitutional Union Party stood in the middle, advocating for unity without change. This centrist approach might seem balanced, but it ignored the urgency of the slavery debate. In a time when moral clarity was needed, the party's ambiguity made it a relic of a bygone era rather than a solution for the future. Its failure to gain traction beyond border states underscores the limits of moderation in a polarized nation.

For those studying political strategies, the Constitutional Union Party serves as a cautionary tale. Its focus on preserving the status quo without addressing underlying conflicts mirrors modern debates where divisive issues are often sidestepped for expediency. The party's brief existence reminds us that unity built on avoidance is fragile and unsustainable. Practical advice for contemporary policymakers: acknowledge contentious issues head-on, even if resolution seems daunting. Sweeping problems under the rug, as the Constitutional Union Party did, only delays the inevitable reckoning.

In retrospect, the Constitutional Union Party's legacy is one of missed opportunity. By refusing to engage with slavery, it failed to offer a viable path forward for a nation on the brink of civil war. Its story is a reminder that political parties must confront, not circumvent, the defining issues of their time. While its intentions were noble, its strategy was flawed, leaving it as a footnote in history rather than a force for lasting change. The party's demise underscores a timeless truth: unity without justice is no unity at all.

The Perils of Political Activism: Risks, Repression, and Resilience

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Before Lincoln's presidency, the major political parties were the Democratic Party and the Whig Party. The Whig Party, which Lincoln was a member of, later dissolved, leading to the rise of the Republican Party.

Yes, the Republican Party was founded in the mid-1850s, primarily in response to the issue of slavery. Lincoln joined the party and became its presidential nominee in 1860.

The Whig Party began to decline in the 1850s due to internal divisions over slavery and other issues. It effectively dissolved by the late 1850s, with many of its members, including Lincoln, joining the newly formed Republican Party.

Yes, the Know-Nothing Party (also known as the American Party) gained prominence in the mid-1850s, focusing on anti-immigration and anti-Catholic sentiments. However, it was short-lived and declined after the 1856 election.