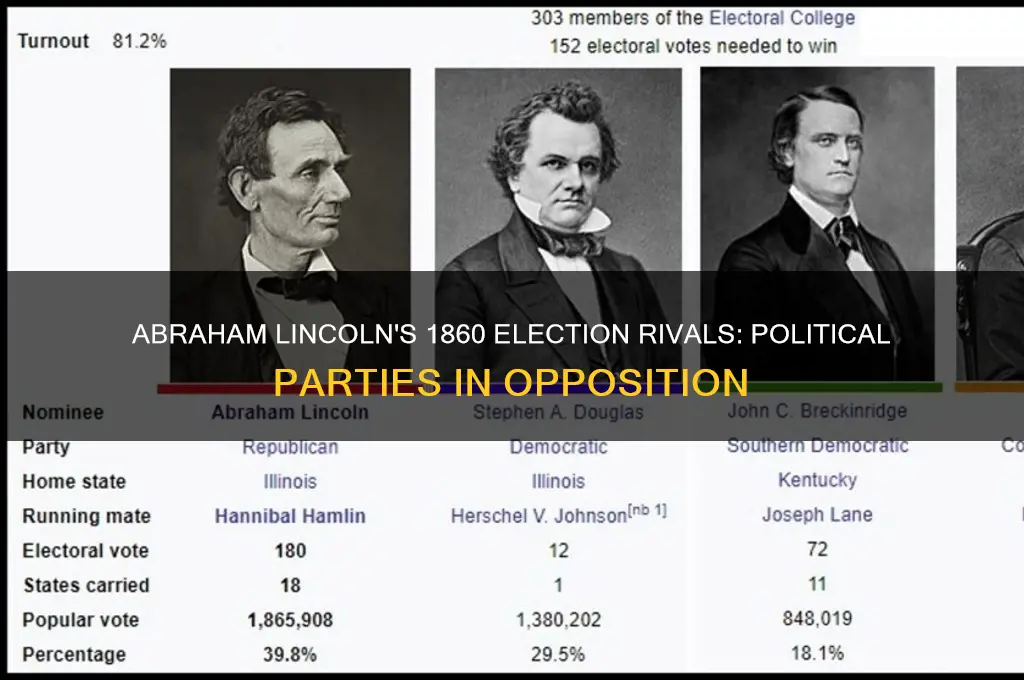

Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States, faced significant opposition during his presidential campaigns, particularly in the 1860 and 1864 elections. In 1860, Lincoln ran as the Republican Party candidate against three major opponents: Stephen A. Douglas of the Northern Democratic Party, John C. Breckinridge of the Southern Democratic Party, and John Bell of the newly formed Constitutional Union Party. This election was deeply divided along regional lines, with Lincoln winning primarily in the North, while the South split its support among the other candidates. In 1864, during the Civil War, Lincoln ran as the candidate of the National Union Party, a coalition of Republicans and War Democrats, against George B. McClellan of the Democratic Party, who advocated for a negotiated peace with the Confederacy. These elections highlight the intense political polarization of the era and the challenges Lincoln faced in uniting a fractured nation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of Major Opposing Parties | 3 |

| Names of Major Opposing Parties (1860 Election) | 1. Democratic Party 2. Constitutional Union Party 3. Southern Democratic Party |

| Democratic Party Candidate (1860) | Stephen A. Douglas |

| Constitutional Union Party Candidate (1860) | John C. Bell |

| Southern Democratic Party Candidate (1860) | John C. Breckinridge |

| Key Issue Driving Opposition | Slavery and its expansion into new territories |

| Regional Support for Opposing Parties | - Democratic Party: Northern Democrats - Constitutional Union Party: Border states - Southern Democratic Party: Deep South |

| Outcome of 1860 Election | Abraham Lincoln won with 180 electoral votes, despite not being on the ballot in many Southern states |

| Impact of Opposition | The split in the Democratic Party and the formation of the Constitutional Union Party helped Lincoln secure victory |

Explore related products

$30.2 $54.99

$36.47 $49.99

What You'll Learn

- Democratic Party: Led by Stephen A. Douglas, emphasizing states' rights and popular sovereignty on slavery

- Constitutional Union Party: Focused on preserving the Union, avoiding secession, and downplaying slavery issues

- Southern Democrats: Split from the main party, advocating for secession and protection of slavery

- Liberty Party: Smaller group pushing for immediate abolition of slavery, though less influential in 1860

- Republican Party: Lincoln's own party, opposing slavery expansion and promoting national unity

Democratic Party: Led by Stephen A. Douglas, emphasizing states' rights and popular sovereignty on slavery

The 1860 presidential election was a pivotal moment in American history, with the Democratic Party, led by Stephen A. Douglas, emerging as a formidable opponent to Abraham Lincoln. At the heart of Douglas's campaign was a staunch defense of states' rights and the principle of popular sovereignty, particularly regarding the contentious issue of slavery. This stance, while appealing to many Southern voters, also highlighted the deep divisions within the Democratic Party itself, which would ultimately contribute to its defeat.

To understand Douglas's strategy, consider the concept of popular sovereignty as a political tool. This principle allowed territories to decide for themselves whether to permit slavery, based on the will of their residents. Douglas argued that this approach respected the autonomy of states and territories, aligning with the Democratic Party's emphasis on limited federal intervention. For instance, in the debates leading up to the election, Douglas famously declared, "It is for the people of a Territory to decide this question for themselves." This position, however, was not without its critics, as it effectively punted the moral question of slavery to local populations, many of which were deeply divided on the issue.

A comparative analysis reveals the stark contrast between Douglas's approach and Lincoln's. While Lincoln opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories, Douglas's popular sovereignty allowed for its potential spread. This difference was not merely ideological but had practical implications. For example, if a territory like Kansas had been admitted as a slave state under Douglas's policy, it could have significantly altered the balance of power in the Senate, further entrenching Southern interests. This scenario underscores the high stakes of the election and the divergent paths the nation could have taken.

From a persuasive standpoint, Douglas's emphasis on states' rights resonated with voters who feared federal overreach. In an era where the role of the central government was hotly debated, his argument that local communities should govern themselves held considerable appeal. However, this focus also exposed a critical vulnerability: it failed to address the moral imperative of slavery, a growing concern among Northern voters. Douglas's inability to reconcile states' rights with the ethical dimensions of slavery alienated key constituencies, ultimately weakening his candidacy.

In practical terms, the Democratic Party's strategy under Douglas offers a cautionary tale about the limits of compromise in the face of moral crises. By prioritizing procedural solutions like popular sovereignty over principled stands, the party risked appearing indifferent to the suffering of enslaved people. This lesson is particularly relevant today, as political leaders navigate complex issues requiring both pragmatism and moral clarity. For those studying political campaigns, the 1860 election serves as a reminder that policies must address not only structural concerns but also the ethical values of the electorate.

In conclusion, Stephen A. Douglas's leadership of the Democratic Party in 1860, with its focus on states' rights and popular sovereignty, was a calculated strategy that both capitalized on and exacerbated the nation's divisions. While it sought to appeal to a broad coalition, its failure to confront the moral issue of slavery proved its undoing. This historical example remains instructive, illustrating the delicate balance between respecting local autonomy and advancing national principles.

Political Dynasties and Dominance: Shaping Global Politics Since 1968

You may want to see also

Constitutional Union Party: Focused on preserving the Union, avoiding secession, and downplaying slavery issues

The 1860 presidential election was a pivotal moment in American history, marked by deep divisions over slavery and states' rights. Amidst this turmoil, the Constitutional Union Party emerged as a unique political force, prioritizing unity over ideology. Formed by former Whigs and Know-Nothing Party members, this party aimed to transcend the polarizing issues of the day, focusing instead on preserving the Union and avoiding secession. Their platform was straightforward: uphold the Constitution and maintain national cohesion, even if it meant sidestepping the contentious topic of slavery.

To understand the Constitutional Union Party’s strategy, consider their candidate, John Bell, a Tennessee politician who embodied the party’s moderate stance. Bell and his supporters believed that by downplaying slavery, they could appeal to both Northern and Southern voters who feared the consequences of disunion. This approach, however, was not without its flaws. By avoiding the moral and economic implications of slavery, the party failed to address the root cause of the nation’s divisions, making their platform seem more like a temporary bandage than a lasting solution.

A closer look at the party’s rhetoric reveals its emphasis on legalism and compromise. They championed the Constitution as the ultimate arbiter of national disputes, arguing that adherence to this document would prevent secession. For instance, they supported the Fugitive Slave Act and the Dred Scott decision, not out of endorsement of slavery, but as a means to uphold the rule of law. This stance, while legally consistent, alienated abolitionists in the North and failed to reassure secessionists in the South, who saw it as insufficiently protective of their interests.

Despite its noble intentions, the Constitutional Union Party’s impact was limited. In the 1860 election, Bell secured only 39 electoral votes, primarily from border states like Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. This outcome underscores the party’s inability to compete with the more ideologically driven platforms of Abraham Lincoln’s Republican Party and the Southern-backed Democratic Party. The Constitutional Union Party’s failure to gain traction highlights the reality that, in times of crisis, moderation often struggles to match the urgency of radical solutions.

In retrospect, the Constitutional Union Party serves as a case study in the challenges of political centrism during extreme polarization. Their focus on preserving the Union was admirable, but their reluctance to confront slavery left them ill-equipped to address the era’s defining issue. For modern observers, this party’s story offers a cautionary tale: unity cannot be achieved by ignoring the underlying causes of division. Instead, it requires addressing those causes head-on, even when doing so is uncomfortable or unpopular.

Is CNN Politically Biased? Uncovering Its Party Affiliations and Allegiances

You may want to see also

Southern Democrats: Split from the main party, advocating for secession and protection of slavery

The 1860 presidential election was a pivotal moment in American history, marked by deep divisions over slavery and states' rights. Among the factions opposing Abraham Lincoln, the Southern Democrats emerged as a distinct and radical force. Having split from the main Democratic Party, they formed their own coalition, nominating John C. Breckinridge as their candidate. Their platform was unapologetically pro-slavery and pro-secession, reflecting the intensifying regional interests of the Deep South. This faction’s rise underscores how internal party fractures can mirror broader societal rifts, ultimately reshaping political landscapes.

To understand the Southern Democrats’ stance, consider their core demands: the protection of slavery as a constitutional right and the assertion that secession was a legitimate response to perceived Northern aggression. Their campaign literature often framed slavery as an economic necessity and a moral good, while portraying Lincoln’s election as an existential threat to Southern way of life. For instance, Breckinridge’s speeches emphasized the "Southern way of life" as inseparable from slave labor, a message that resonated deeply in states like South Carolina and Mississippi. This rhetoric was not just political posturing but a call to arms, both literal and ideological.

Analytically, the Southern Democrats’ split reveals the fragility of national parties when regional interests dominate. Unlike the Constitutional Union Party, which sought compromise, or the Northern Democrats, who focused on union preservation, the Southern Democrats embraced extremism. Their strategy was twofold: first, to galvanize Southern voters through fear and identity politics, and second, to lay the groundwork for secession if Lincoln won. This approach highlights how political parties can become vehicles for division rather than unity, particularly when ideological purity is prioritized over coalition-building.

Practically, the Southern Democrats’ influence extended beyond the ballot box. Their advocacy for secession directly contributed to the formation of the Confederate States of America following Lincoln’s victory. For historians or educators exploring this period, examining primary sources like the Declaration of the Immediate Causes of Secession issued by South Carolina can provide insight into the mindset of this faction. Similarly, comparing Breckinridge’s campaign platform to Lincoln’s debates offers a stark contrast in visions for America’s future.

In conclusion, the Southern Democrats were not merely another party opposing Lincoln; they were a symptom and catalyst of the nation’s impending fracture. Their unwavering commitment to slavery and secession transformed them from a political faction into a revolutionary movement. Studying their rise and fall offers a cautionary tale about the dangers of prioritizing regional interests over national cohesion, a lesson as relevant today as it was in 1860.

Unveiling the KKK's Origins: Political Party Involvement Examined

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Liberty Party: Smaller group pushing for immediate abolition of slavery, though less influential in 1860

The Liberty Party, though a smaller faction in the 1860 political landscape, played a pivotal role in shaping the national conversation on slavery. Founded in the 1840s, the party emerged as a radical voice advocating for the immediate and unconditional abolition of slavery, a stance that set it apart from more moderate or politically pragmatic groups. By 1860, while its influence had waned compared to larger parties like the Republicans or Democrats, the Liberty Party’s unwavering commitment to abolition kept the issue at the forefront of public discourse. This persistence helped lay the groundwork for the eventual passage of the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment.

To understand the Liberty Party’s impact, consider its strategic focus on moral persuasion over political compromise. Unlike the Republican Party, which prioritized preventing the expansion of slavery into new territories, the Liberty Party demanded its complete eradication. This uncompromising stance resonated with a dedicated but limited base, primarily consisting of religious abolitionists and radical reformers. For instance, the party’s 1840 platform explicitly called for the immediate abolition of slavery in all U.S. territories, a position that, while ethically bold, alienated more moderate voters. This ideological purity, while admirable, constrained its electoral success but amplified its moral influence.

A practical takeaway from the Liberty Party’s approach is the importance of niche movements in driving broader societal change. While the party’s direct political impact in 1860 was minimal, its relentless advocacy pressured larger parties to address slavery more forcefully. For modern activists, this underscores the value of maintaining a clear, principled stance even when immediate political gains seem unlikely. The Liberty Party’s legacy reminds us that smaller groups can catalyze significant shifts by keeping critical issues in the public eye, even if they don’t win elections.

Comparatively, the Liberty Party’s trajectory highlights the tension between ideological purity and political pragmatism. While the Republican Party’s more moderate stance on slavery allowed it to build a broader coalition and ultimately win the presidency with Abraham Lincoln, the Liberty Party’s uncompromising position ensured that abolition remained a non-negotiable moral imperative. This contrast illustrates the dual roles of radical and moderate movements in social change: radicals push boundaries, while moderates consolidate gains. For those engaged in advocacy today, balancing these approaches is key to achieving both short-term victories and long-term transformation.

Finally, the Liberty Party’s story serves as a cautionary tale about the limitations of moral absolutism in a politically diverse society. While its members were undeniably on the right side of history, their inability to adapt their message to a wider audience restricted their influence. Modern activists can learn from this by pairing principled stances with strategic outreach, ensuring that their message resonates beyond a core group of supporters. The Liberty Party’s legacy is not just in its ideals but in the lessons it offers on how to effectively drive change in a complex political landscape.

Step-by-Step Guide to Registering for Your Political Party Primary

You may want to see also

Republican Party: Lincoln's own party, opposing slavery expansion and promoting national unity

The Republican Party, Abraham Lincoln’s political home, emerged in the 1850s as a coalition united by a singular, radical idea: halting the spread of slavery. This wasn’t mere moral posturing; it was a strategic, calculated stance. By confining slavery to its existing territories, Republicans aimed to starve the institution of its lifeblood—economic and political power. Lincoln’s election in 1860 on this platform wasn’t just a victory for his party; it was a direct challenge to the Southern way of life, triggering secession and the Civil War. The party’s anti-slavery expansion plank wasn’t about immediate abolition but about long-term suffocation of the institution, a pragmatic approach that set them apart from more radical abolitionists.

To understand the Republican Party’s appeal, consider their dual focus: opposition to slavery’s expansion and a commitment to national unity. They framed their stance not as a Northern attack on the South but as a defense of the Union’s founding principles. Lincoln’s speeches, like the Cooper Union Address, emphasized preserving the nation for future generations, a message that resonated with moderate voters. The party’s ability to balance moral conviction with practical politics was its strength. For instance, the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, which repealed the Missouri Compromise, galvanized Republicans by exposing the dangers of slavery’s unchecked growth. This event became a rallying cry, proving the party’s prescience and resolve.

A closer look at the Republican Party’s strategy reveals a masterclass in coalition-building. They united former Whigs, Free Soilers, and anti-slavery Democrats under a common cause. Their 1860 platform wasn’t just about slavery; it included tariffs, internal improvements, and homesteading—policies designed to appeal to diverse interests. This inclusivity allowed them to dominate Northern politics, but it also made them a target. Southerners viewed the party as a threat to their economic and social order, while Northern Democrats accused them of extremism. Yet, the Republicans’ unwavering stance on slavery’s containment proved decisive, as it drew a clear line between their vision of America and that of their opponents.

Practical takeaways from the Republican Party’s approach are still relevant today. Their success hinged on framing a divisive issue as a matter of national survival, not regional conflict. Modern political movements could learn from this by emphasizing shared values over partisan divides. For instance, addressing climate change or economic inequality requires similar unity of purpose. The Republicans’ ability to stay focused on their core principle—opposing slavery’s expansion—amidst intense opposition offers a lesson in resilience. It’s a reminder that principled, strategic action can reshape a nation, even in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds.

Will Green: Revolutionizing Political Consulting with Sustainable Strategies and Vision

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The main political parties opposing Abraham Lincoln in 1860 were the Democratic Party, which split into Northern and Southern factions, and the Constitutional Union Party, formed by former Whigs and Know-Nothings.

The Democratic Party had two main candidates due to its split: Stephen A. Douglas (Northern Democrats) and John C. Breckinridge (Southern Democrats).

The Constitutional Union Party focused on preserving the Union and avoided taking a stance on slavery, appealing to moderate voters in the border states.

Yes, the Southern Democrats ran John C. Breckinridge, and the Know-Nothing Party (also known as the American Party) ran John Bell under the Constitutional Union Party banner.

The split in the Democratic Party divided the anti-Lincoln vote, allowing Lincoln to win the election with a plurality of the popular vote and a majority of the electoral vote.