Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that law enforcement must warn a person of their constitutional rights before interrogation, or their statements cannot be used as evidence. Ernesto Miranda was accused of a serious crime and brought into custody, but he was not informed of his right to remain silent or his right to an attorney. The Supreme Court's decision centred on the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which protects individuals from self-incrimination. The ruling had a significant impact on law enforcement, making the Miranda warning part of routine police procedure.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Decision | The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favour of Miranda, overturning his conviction and remanding his case back to Arizona for retrial |

| Constitutional Issue | Whether law enforcement must warn a person of their constitutional rights before interrogating them |

| Date | June 13, 1966 |

| Landmark | Yes |

| Petitioner | Ernesto Miranda |

| Accusation | Kidnapping and rape |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The right to remain silent

In 1963, Ernesto Miranda was arrested and accused of kidnapping and rape. He was brought into custody but was not informed of his right to remain silent or his right to an attorney. Miranda confessed and was convicted, receiving a sentence of 20 to 30 years' imprisonment.

Miranda appealed his conviction, arguing that his constitutional rights had been violated. On June 13, 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a landmark decision in Miranda's favor, overturning his conviction and establishing the principle that law enforcement must inform individuals of their constitutional rights before interrogation. This became known as the "Miranda warnings" or "Miranda rights."

The Miranda v. Arizona case specifically addressed the right to remain silent and the right to an attorney under the Fifth Amendment. The Court ruled that any statements made by a defendant in custody during an interrogation are admissible as evidence only if law enforcement informed the defendant of these rights before the interrogation and if the defendant voluntarily waived them. This ruling established that the right to remain silent is a fundamental constitutional protection, and its violation could result in the exclusion of evidence obtained during interrogation.

The impact of the Miranda v. Arizona decision was significant, as it set a precedent for law enforcement practices across the United States. It ensured that individuals in custody were aware of their rights and provided protections against self-incrimination. However, there have been debates and challenges to the interpretation and application of Miranda rights, with some arguing that Miranda warnings are not constitutionally mandated. For example, in Dickerson v. United States (2000), the validity of Congress's overruling of Miranda was tested, and in Vega v. Tekoh (2022), the Supreme Court ruled that not every Miranda violation is a deprivation of a constitutional right.

The Constitution's Religious Freedom Safeguards

You may want to see also

The right to an attorney

In 1963, Ernesto Miranda was arrested and accused of kidnapping and rape. He was sentenced to 20 to 30 years in prison on each count. During his arrest, Miranda was not informed of his right to remain silent or his right to an attorney, and he confessed to the crimes. Miranda appealed his conviction, arguing that his constitutional rights had been violated.

The case, Miranda v. Arizona, reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1966. The Court ruled in Miranda's favor, finding that law enforcement must inform individuals of their constitutional rights, including the right to remain silent and the right to an attorney, before interrogating them. This ruling established the famous "Miranda warnings" that are now standard in police procedure.

The impact of the Miranda ruling on the right to an attorney has been significant. It ensures that individuals are aware of their right to legal counsel during questioning and can make informed decisions about whether to exercise that right. The ruling also provides a critical safeguard against coercive or manipulative interrogation tactics, helping to ensure that any confessions or statements are made voluntarily and intelligently.

However, the Miranda warnings and the right to an attorney have been the subject of ongoing debate and legal challenges. Some argue that the warnings are not constitutionally required and are instead a matter of judicial policy. In 2000, in Dickerson v. United States, the validity of Congress's overruling of Miranda through § 3501 was tested, and the Miranda warnings were upheld. More recently, in Vega v. Tekoh (2022), the Supreme Court ruled that not every Miranda violation is a deprivation of a constitutional right, indicating that the right to an attorney is still evolving in its interpretation and application.

Massachusetts Constitution: A Pioneer in American Democracy

You may want to see also

Constitutional rights before interrogation

In 1963, Ernesto Miranda was arrested at his home and taken into custody at a Phoenix police station. He was accused of a serious crime, kidnapping and rape, and sentenced to 20 to 30 years' imprisonment on each count. However, the police did not inform him of his right to remain silent or his right to an attorney—his constitutional rights before interrogation.

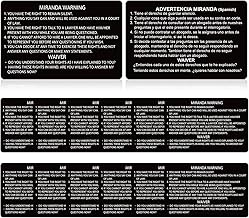

Miranda v. Arizona (1966) was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court, in which the Court ruled that law enforcement must warn a person of their constitutional rights before interrogation, or their statements cannot be used as evidence at their trial. This ruling was based on the Fifth Amendment, which states that any statements made by a defendant in custody during an interrogation are admissible as evidence only if the defendant was informed of their right to remain silent and their right to an attorney before the interrogation. These rights must be waived in a knowing, voluntary, and intelligent manner.

The Supreme Court's decision in Miranda v. Arizona set a precedent for the constitutional rights of individuals during police interrogation. It established that individuals have the right to remain silent and the right to an attorney during questioning. These rights are designed to protect individuals from self-incrimination and ensure that any statements made during an interrogation are voluntary and intelligent.

The case of Miranda v. Arizona highlights the importance of constitutional rights during police interrogation. It is a reminder that individuals have the right to remain silent and the right to an attorney, and that law enforcement must respect and uphold these rights. Failure to do so can result in evidence being ruled inadmissible in court.

While Miranda v. Arizona established important constitutional rights for individuals during interrogation, subsequent cases have clarified and challenged these rights. For example, in Dickerson v. United States (2000), the validity of Congress's overruling of Miranda through § 3501 was tested. The Supreme Court upheld the Miranda ruling, affirming that the Miranda warnings were compelled by the Constitution. However, in Vega v. Tekoh (2022), the Supreme Court ruled that police officers could not be sued for failing to administer the Miranda warning, as not every Miranda violation is a deprivation of a constitutional right.

US Constitution: A Global Inspiration for Democracy

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Validity of the Miranda warnings

In the landmark case of Miranda v. Arizona, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that law enforcement must warn individuals of their constitutional rights before interrogating them, specifically under the Fifth Amendment. This ruling established the well-known "Miranda warnings," which include the right to remain silent, the right to an attorney, and the right against self-incrimination. The validity of these warnings has been widely debated and has had a significant impact on police procedures and criminal prosecutions.

The validity of Miranda warnings stems from the Supreme Court's recognition of the inherent pressures and compelling nature of custodial interrogations. The Court held that without proper safeguards, the interrogation process could undermine an individual's will to resist and compel them to speak. As a result, the Miranda warnings were established to protect the rights of individuals during police questioning.

The validity of Miranda warnings is evident in the specific requirements outlined by the Supreme Court. These warnings must be provided to individuals before any questioning begins. Suspects must be informed of their right to remain silent, that anything they say can be used against them in court, their right to have an attorney present during questioning, and their right to a court-appointed attorney if they cannot afford one. These warnings ensure that individuals are aware of their rights and can make informed decisions during police interrogations.

The validity of Miranda warnings is further supported by the requirement that individuals must voluntarily, knowingly, and intelligently waive these rights for any statements to be used as evidence in their trial. This means that law enforcement must obtain a clear and affirmative waiver from the suspect, ensuring that they understand their rights and choose to waive them voluntarily. In the case of Miranda v. Arizona, the defendant did not receive a full and effective warning of his rights, and his subsequent confession was ruled inadmissible by the Supreme Court.

While Miranda warnings have faced criticism and legal challenges, they remain a critical aspect of the American criminal justice system. The validity of these warnings has been reaffirmed in subsequent cases, such as Dickerson v. United States, where the Supreme Court upheld the validity of Miranda warnings and reversed Congress's attempt to overrule them. The validity of Miranda warnings also extends to ensuring that individuals with limited understanding or language barriers receive proper interpretation and comprehension of their rights.

In conclusion, the validity of Miranda warnings lies in their ability to safeguard the constitutional rights of individuals during police interrogations. By requiring law enforcement to inform suspects of their rights and obtaining a voluntary and knowing waiver, Miranda warnings protect against self-incrimination and ensure a fair and just criminal justice process. While there have been efforts to limit their scope, Miranda warnings continue to play a crucial role in preserving the rights of the accused.

AP Exam Grades: Understanding the Scoring System

You may want to see also

Admissibility of confessions

In Miranda v. Arizona, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that law enforcement must inform individuals of their constitutional rights before any custodial interrogation. This includes the right to remain silent and the right to consult an attorney. The ruling established that confessions obtained without these warnings are inadmissible in court.

Ernesto Miranda was accused of a serious crime and taken into police custody for interrogation. During the interrogation, Miranda confessed to the crime, but he was not informed of his right to remain silent or his right to an attorney. Miranda's oral and written confessions were obtained without him being aware of his constitutional rights, which set a precedent for the admissibility of confessions in future cases.

The Supreme Court's decision in Miranda v. Arizona established that the admissibility of confessions depends on whether the individual was informed of their constitutional rights. This ruling has been upheld and reinforced in subsequent cases, such as Dickerson v. United States, where the validity of Congress's overruling of Miranda was tested. The Court affirmed that Miranda warnings are compelled by the Constitution and are not just judicial policy.

The impact of Miranda v. Arizona on the admissibility of confessions is significant. It ensures that individuals are aware of their rights during police interrogations and protects them from self-incrimination. The ruling also provides guidelines for law enforcement to follow during interrogations, ensuring that any confessions obtained can be used as evidence in court. However, it's important to note that not every Miranda violation is considered a deprivation of constitutional rights, as seen in the case of Vega v. Tekoh (2022).

In conclusion, Miranda v. Arizona established the requirement for law enforcement to inform individuals of their constitutional rights before interrogation, with the admissibility of confessions depending on whether these warnings were given. This ruling continues to shape police procedures and the protection of individuals' rights during interrogations.

The Constitution: Empowering the People

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Ernesto Miranda was accused of a serious crime and arrested at his home on March 13, 1963. He was then taken into custody at a Phoenix police station, where he confessed to the crime. However, the police did not inform him of his right to remain silent or his right to an attorney.

The constitutional issue in Miranda v. Arizona centred around the Fifth Amendment and the right against self-incrimination. The case addressed whether statements obtained from an individual during custodial police interrogation could be admissible as evidence in court if the individual was not informed of their constitutional rights.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 decision in favour of Miranda, overturning his conviction and remanding the case back to Arizona for retrial. The Court held that under the Fifth Amendment, the government could not use a person's statements made during police interrogation as evidence at their criminal trial unless they were informed of their rights and voluntarily waived them.

Miranda v. Arizona had a significant impact on law enforcement in the United States, leading to the creation of the "Miranda warnings" or "Miranda rights." Law enforcement agencies were required to ensure that suspects were informed of their rights, including the right to remain silent and the right to consult with an attorney, before any interrogation.

Yes, Miranda v. Arizona has faced challenges, such as in Dickerson v. United States (2000), where the validity of Congress's overruling of Miranda was tested. The Court upheld Miranda, stating that the warnings had "become part of our national culture." However, there have been dissenting opinions, with some arguing that Miranda warnings are not constitutionally required.