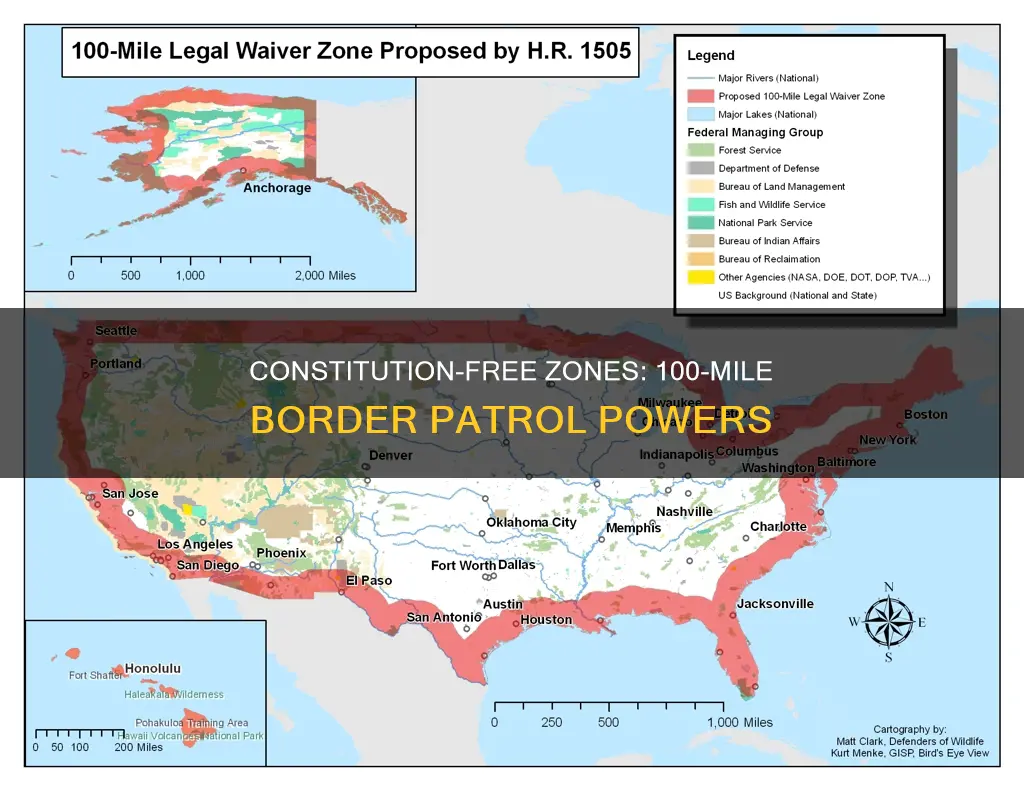

The 100-mile constitution-free zone refers to a region within 100 miles of any US external boundary, including borders with Mexico and Canada and coastlines, where federal regulations give US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) expanded powers. CBP agents can operate immigration checkpoints, board public transportation, and search people and their belongings without a warrant or reasonable suspicion of wrongdoing. This affects around 200 million people, including residents of many of the largest US cities, and has led to concerns about the erosion of constitutional rights and the militarization of the border zone.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A 100-mile border zone where the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution does not fully apply |

| Population | 200 million people, including residents of nine of the ten largest U.S. cities |

| Border Patrol Jurisdiction | U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents can board public transportation or set up interior checkpoints without a warrant or reasonable suspicion |

| Border Patrol Actions | Questioning, interrogation, and searches |

| Individual Rights | Right to remain silent, right to decline to answer questions, right to request the presence of an attorney |

| Border Search Exception | Federal law allows certain federal agents to conduct searches and seizures within 100 miles of the border |

| Constitutional Issues | Violation of Fourth Amendment rights, inadequate training of Border Patrol agents, lack of oversight by CBP and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Border Patrol agents can board public transport without a warrant

- Border Patrol agents can operate immigration checkpoints

- Your rights: you are not required to answer and can remain silent

- The Fourth Amendment: protects against arbitrary searches and seizures

- Border technologies: watch lists, advanced ID systems, and drones

Border Patrol agents can board public transport without a warrant

The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects people from random and arbitrary stops and searches. However, the federal government claims the power to conduct certain kinds of warrantless stops within 100 miles of the U.S. border. This area is known as the "100-mile border zone" or "100-mile constitution-free zone".

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is tasked with patrolling the U.S. border and areas that function like a border. CBP claims authority to board a bus or train without a warrant anywhere within this 100-mile zone. This is because a federal law says that, without a warrant, CBP can board vehicles and vessels and search for people without immigration documentation “within a reasonable distance from any external boundary of the United States.” The federal government defines a "reasonable distance" as 100 air miles from any U.S. external boundary.

In practice, CBP boards buses and trains in the 100-mile border region either at the station or while the bus is on its journey. More than one officer usually boards the bus, and they will ask passengers questions about their immigration status and ask to see immigration documents. These questions should be brief and related to verifying one’s lawful presence in the U.S. Although these situations can be scary, and it may seem that CBP agents are giving an order, passengers are not required to answer and can simply say they do not wish to do so. As always, passengers have the right to remain silent.

If a passenger refuses to answer CBP’s questions, the agent may persist with questioning. If this occurs, the passenger should ask if they are being detained, or if they are free to leave. If the agent wishes to detain the passenger, they need at least reasonable suspicion that the passenger committed an immigration offense or violated federal law for their actions to be lawful.

Meta Tags and Trademark Infringement: What's the Legal Risk?

You may want to see also

Border Patrol agents can operate immigration checkpoints

The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects people from random and arbitrary stops and searches. However, the federal government claims the power to conduct certain kinds of warrantless stops within 100 miles of the U.S. border. This area is known as the "100-mile border zone" or the "border zone". Within this zone, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents have the authority to operate immigration checkpoints.

CBP agents can board buses and trains in the 100-mile border region either at the station or while the bus is on its journey. Usually, more than one officer will board and ask passengers questions about their immigration status and ask to see their immigration documents. Passengers are not required to answer and can simply say they do not wish to do so, or they can remain silent. Refusing to answer may result in further questioning or being referred to secondary inspection.

CBP operates immigration checkpoints along the interior of the United States at both major roads (permanent checkpoints) and secondary roads ("tactical checkpoints"). At these checkpoints, every motorist is stopped and asked about their immigration status. Agents do not need any suspicion to stop and ask questions at a lawful checkpoint, but their questions should be brief and related to verifying immigration status. They can also visually inspect a vehicle. Motorists who are sent to secondary inspection areas will undergo further questioning, which should be limited and routine. It is a felony to flee from an immigration checkpoint.

If an agent extends the stop to ask questions unrelated to immigration enforcement or extends the stop for a prolonged period to ask about immigration status, the agent needs at least reasonable suspicion that the person has committed an immigration offense or violated federal law for their actions to be lawful. If a person is held at the checkpoint beyond brief questioning, they can ask the agent if they are free to leave. If the agent says no, they need reasonable suspicion to continue holding the person. The agent should be able to articulate their suspicion if asked. If the agent arrests the person or searches the interior of their belongings, they need probable cause that the person committed an offense.

The Constitution's Impact on American Slavery Status Quo

You may want to see also

Your rights: you are not required to answer and can remain silent

The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects people from random and arbitrary stops and searches. However, the federal government claims the power to conduct certain kinds of warrantless stops within 100 miles of the U.S. border, which is referred to as the "100-mile border zone". This zone includes international land borders and the entire U.S. coastline.

Within this zone, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents may board buses and trains to ask passengers questions about their immigration status and ask to see their immigration documents. Although these situations can be intimidating, and it may seem that CBP agents are giving an order, individuals are not required to answer and can simply say they do not wish to do so.

If an individual does not want to answer questions, they can inform the agent that they decline to answer, or that they will only answer questions in the presence of an attorney. Refusing to answer will likely result in further detention for questioning, being referred to secondary inspection, or both. If an agent extends the stop to ask questions unrelated to immigration enforcement or extends the stop for a prolonged period to ask about immigration status, the agent needs at least reasonable suspicion that the individual committed an immigration offense or violated federal law for their actions to be lawful. If held for more than brief questioning, individuals can ask if they are free to leave, and if the agent says no, they need reasonable suspicion to continue holding them.

It is important to note that separate rules apply at international borders and airports, and for individuals on certain nonimmigrant visas, including tourists and business travelers. At border crossings, federal authorities do not need a warrant or even suspicion of wrongdoing to justify conducting a "routine search", such as searching luggage or a vehicle. Customs officers can ask about immigration status to determine whether someone has the right to enter the country. If a U.S. citizen, one only needs to answer questions establishing their identity and citizenship, although refusing to answer routine questions about the nature and purpose of the travel could result in delay and/or further inspection. If a non-citizen, one may decline to answer general questions about religious beliefs and political opinions, but this may lead to denial of entry into the country.

Citing the US Constitution: Turabian Style Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The Fourth Amendment: protects against arbitrary searches and seizures

The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects people from random, arbitrary, and unreasonable searches and seizures. It requires the government to obtain a warrant based on probable cause to conduct a legal search and seizure. This means that police cannot search a person or their property without a warrant or probable cause.

The Fourth Amendment also applies at the border, including international airports in the U.S. and within 100 miles of any U.S. "external boundary". This 100-mile border zone is an area where federal regulations give U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) the authority to operate. Here, CBP agents can board a bus or train without a warrant and ask passengers about their immigration status. However, it is important to note that you are not required to answer and can simply say that you do not wish to do so. You have the right to remain silent, and if you are held at the checkpoint for more than brief questioning, you can ask if you are free to leave.

The Supreme Court has interpreted the Fourth Amendment's protections in several landmark cases. For example, in Katz v. United States (1967), the Court ruled that installing a wiretap without a warrant constituted a search under the Fourth Amendment, introducing the concept of a "reasonable expectation of privacy". In Mapp v. Ohio (1961), the Court held that the Fourth Amendment's protections apply to state courts and that evidence obtained in violation of the amendment is inadmissible in those courts.

While the Fourth Amendment provides important protections, technological advancements have expanded the government's ability to search and surveil people, raising questions about what constitutes a "search" under the amendment. Additionally, the expansion of government power at and near the border has led to concerns about the erosion of constitutional rights.

Florida Public School Absenteeism: What Counts as an Absence?

You may want to see also

Border technologies: watch lists, advanced ID systems, and drones

Border security is an essential part of a country's defence and a critical concern for governments worldwide. The challenges of preventing terrorism, unauthorized immigration, and drug trafficking have led to the development and deployment of numerous technologies. These technologies aim to reduce unlawful entry by migrants and the smuggling of dangerous items through ports of entry.

One such technology is the use of watch lists and database systems. For example, the Automated Targeting System is a traveler risk assessment program that helps identify potential threats. These systems are often operated by border patrol agents who must understand and use data from interconnected sensing technologies.

Advanced identification and tracking systems, such as biometric identification and electronic passports, are also being used at airports and other ports of entry. While these systems aim to improve security, they have faced criticism from civil liberties watchdogs due to their potential negative impact on legal migrants and asylum seekers. Additionally, there is concern among the public about law enforcement's responsible use of this technology.

Unmanned aerial vehicles, or "drone aircraft," are another tool used in border surveillance. These drones enhance agents' situational awareness and enable them to silently identify and track unauthorized border crossers. The drones can send tracking coordinates and use lasers to provide precise location information to agents on the ground.

The use of these technologies in the 100-mile border zone, where the Fourth Amendment protections against arbitrary searches and seizures are limited, raises concerns about the balance between security and individual rights. The expansion of government power at and near the border has led to increased scrutiny by civil liberties organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

Citing the US Constitution: Bluebook Style Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The 100-mile constitution-free zone is a term used to describe the area within 100 miles of any US external boundary, where federal regulations give US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) authority to operate without a warrant. This includes borders with Mexico and Canada, as well as coastlines.

CBP officers can board buses and trains within the 100-mile zone to ask passengers about their immigration status and to see their immigration documents. They can also set up interior checkpoints and stop, interrogate and search people without a warrant or reasonable suspicion.

Although the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution protects Americans from random and arbitrary stops and searches, these rights do not apply fully at US borders. However, you do have the right to remain silent and not answer CBP officers' questions. If you are held for more than brief questioning, you can ask if you are free to leave.

According to the 2010 census, about 200 million people live within the 100-mile zone, including residents of nine of the ten largest US cities, such as New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago.