The United States Constitution is a foundational document that outlines the powers and responsibilities of the federal government. It is composed of various clauses, each serving a specific purpose and addressing different aspects of governance. These clauses are the result of careful deliberation and compromise between the founding fathers, aiming to establish a balanced and effective system of government. From ensuring fair representation in the House of Representatives to delegating powers for taxation and commerce regulation, the clauses form the framework that guides the nation's laws and policies. While some clauses have faced scrutiny for their ambiguity or changing relevance in modern times, they collectively form the backbone of America's democratic principles and continue to shape the country's political landscape.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Powers of Congress | Laying and collecting taxes, duties, imposts, and excises |

| Regulating commerce with foreign nations and among the states | |

| Establishing uniform rules of naturalization and bankruptcy laws | |

| Calling forth the Militia to execute laws, suppress insurrections, and repel invasions | |

| Organizing, arming, and disciplining the Militia | |

| Compromise between large and small states | Larger states get more representation in the House of Representatives, while all states get equal representation in the Senate |

| Preventing federal officers from favoring foreign governments | Ensuring officers do not receive favors or "emoluments" in return for money or other benefits |

| Presidential appointments | Granting the president the power to make unilateral appointments when the Senate is not in session |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Compromise between large and small states

The delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787 were tasked with deciding how the states were to be represented in the new government. This issue was the most controversial aspect of the drafting of the Constitution.

The Virginia Plan, drafted by James Madison, proposed a bicameral legislature with proportional representation in both houses, meaning that states with larger populations would have more seats. Delegates from small states objected to this idea, arguing that each state, regardless of its population, should have equal representation in the legislature. Delegates from larger states countered that their states contributed more financially and defensively to the nation, and therefore deserved a greater say in the central government.

The dispute between small and large states spurred intense debates, with key delegates James Madison and James Wilson driving the debate, although they lost on many key issues. Madison, for example, continued to press his case for proportional representation in the Senate. The small-state delegates, on the other hand, threatened to unravel the proceedings if their demands were not met.

To resolve these differences, the Convention delegates formed a compromise committee, which proposed the "Great Compromise" or the "Connecticut Compromise". This plan, which passed by a single vote, established equal representation in the Senate and proportional representation in the House of Representatives. Chief Justice Warren Burger later explained that this compromise, by dividing the legislature into two branches, allayed the fears of both the large and small states.

Axis and Allies: Key Nations in World War II

You may want to see also

Preventing federal officers from accepting foreign bribes

The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) and the Foreign Extortion Prevention Act (FEPA) are two key pieces of legislation that address the issue of foreign bribes and corruption.

The FCPA prohibits the willful use of mails or any means of interstate commerce to offer, promise, or authorise the payment of money or anything of value to any person, with the knowledge that it will be offered to a foreign official. This act also covers the inducement of foreign officials to violate their lawful duties or to secure improper advantages to obtain or retain business. The FCPA establishes anti-bribery provisions that aim to prevent corruption and maintain integrity in international business dealings.

The FEPA, enacted in July 2024, complements the FCPA by criminalising the "demand side" of foreign bribery. It makes it a crime for foreign officials or those selected to be foreign officials to corruptly demand, seek, receive, accept, or agree to receive payments from certain classes of persons and entities. These classes include issuers, domestic concerns, and their officers, directors, employees, agents, or stockholders. The FEPA enforces strict consequences for violations, including up to 15 years of imprisonment and a maximum fine of $250,000 or three times the monetary equivalent of the bribe.

In the context of preventing federal officers from accepting foreign bribes, the FCPA and FEPA work together to deter and punish such acts. The FCPA focuses on prohibiting individuals and entities from offering bribes, while the FEPA specifically targets foreign officials who demand or accept those bribes.

Additionally, the concept of bribery in the context of public officials is addressed in Section 201 of Title 18, which distinguishes between bribery and gratuities. Bribery, as defined in Section 201(b), involves a direct connection between the giving or receiving of something of value and the performance of an official act. It carries a more severe punishment of up to 15 years in prison. On the other hand, gratuities, as outlined in Section 201(c), involve a looser connection between the payment and the official act, such as a gift given as "thanks" after the act or to "curry favor." Gratuities are punishable by a maximum sentence of 2 years.

These laws collectively contribute to the prevention of federal officers from accepting foreign bribes by establishing clear prohibitions, consequences, and distinctions between bribery and related concepts.

USS Constitution: A Naval Battle to Remember

You may want to see also

Congressional power over the debt ceiling

The debt ceiling, also known as the debt limit, is the maximum amount of debt that the US government is allowed to accumulate through various debt instruments. The US first instituted a statutory debt limit with the Second Liberty Bond Act of 1917, which set limits on the total debt that could be accumulated through individual categories of debt.

Congress has significant power over the debt ceiling, and since 1960, it has acted 78 times to raise, temporarily extend, or revise the debt limit. This includes 49 actions under Republican presidents and 29 under Democratic presidents. Congressional leaders from both parties have recognized the necessity of raising the debt ceiling when required.

The debt ceiling does not authorize new spending; instead, it allows the government to finance existing legal obligations. Failing to increase the debt ceiling when necessary would result in the government defaulting on its legal obligations, leading to a financial crisis with severe consequences for the US economy and its citizens.

While some economists and politicians argue for raising the debt ceiling to avoid financial turmoil, others, including proponents of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), critique the concept of the debt ceiling itself. MMT theorists argue that governments have the power to create and spend money within reasonable limits without creating hyperinflation. In contrast, orthodox economic theorists tend to focus on the national deficit as a debt that needs eventual repayment.

The Texas Constitution: A Concise Document

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

Unilateral presidential appointments

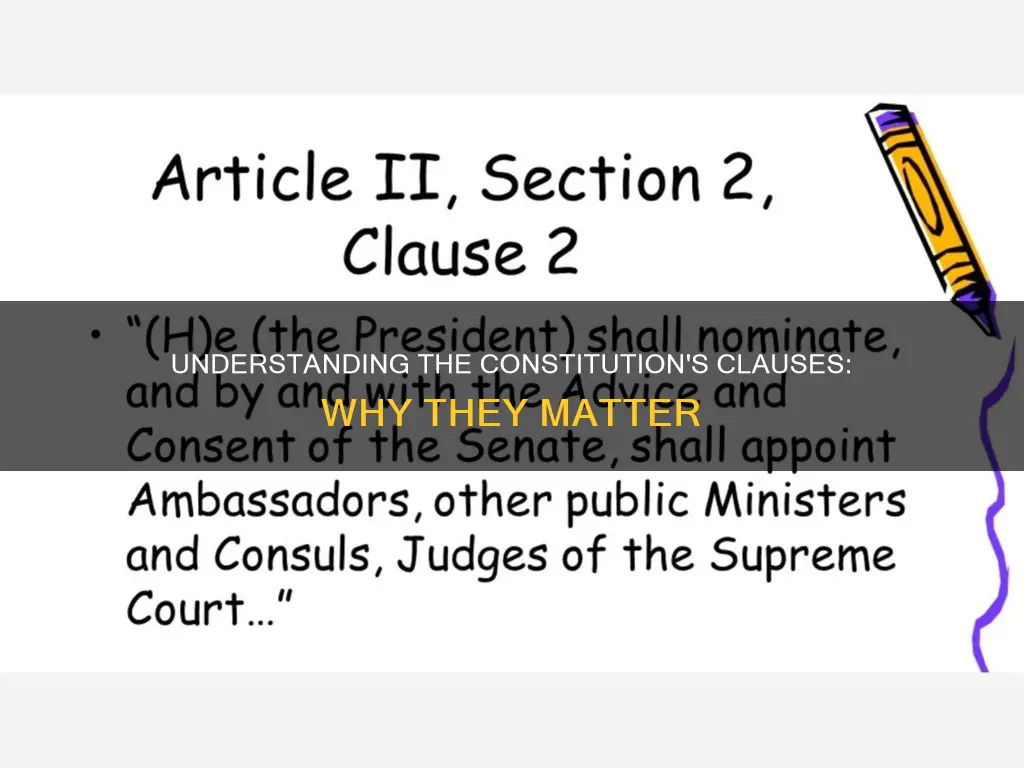

The Appointments Clause in Article II, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution grants the president significant powers to influence the federal government's leadership. The clause gives the president the authority to nominate and, with the advice and consent of the Senate, appoint ambassadors, ministers, consuls, and judges. The Senate's role is advisory, and the president is not obligated to follow their advice. This ensures accountability and prevents tyranny.

The Appointments Clause also distinguishes between two types of officers: principal officers and inferior officers. Principal officers, such as Supreme Court justices, must be appointed by the president with the Senate's consent. On the other hand, inferior officers are those whose appointment Congress may place with the president, judiciary, or department heads. Examples of inferior officers include district court clerks, federal supervisors of elections, and independent counsel.

The framers of the Constitution were concerned about Congress exercising the appointment power and filling offices with their supporters, undermining the president's control over the executive branch. The Appointments Clause acts as a restraint on Congress and maintains the separation of powers. It prevents Congress from making appointments directly or unilaterally appointing incumbents to new offices under the guise of legislating new duties.

The Appointments Clause also provides for recess appointments, where the president can make appointments during a Senate recess, which usually require Senate confirmation. This power is granted by Article II, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution.

The Commission Clause in Article II, Section 3 mandates that the president "shall commission all the Officers of the United States." The president issues formal commissions, or 'documents of empowerment', to those selected to fill specific roles, authenticating their appointment and authority.

Civil Liberties: Our Constitutional Rights Explained

You may want to see also

Congress's power to organise militias

The US Constitution commits organizing and providing for the militia to Congress. The Militia Clause of the Constitution brought the militia, which had been a state institution, under the control of the federal government. The act divided the "militia of the United States" into several classes of organized militias, including the National Guard.

The Militia Act of 1795 delegated to the President the power to call out the militia, and this was held constitutional. The act also authorized the President, in certain emergencies, to draft members of the National Guard into military service. The Federal Government may call out the militia in case of civil war or to suppress rebellion.

Congress's power over the militia is considered to be unlimited, except in the two particulars of officering and training them under the Militia Clauses. The states, as well as Congress, may prescribe penalties for failing to obey the President's call of the militia. They also have the concurrent power to aid the National Government with calls under their own authority, and in emergencies, they may use the militia to put down armed insurrection.

The Judiciary is precluded from exercising oversight over the process of organizing and providing for the militia. However, wrongs committed by troops are subject to judicial relief in damages.

Founding Fathers: Slave Owners and the Constitution

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The clauses in the US Constitution outline the powers and responsibilities of the federal government, defining its role and scope in relation to the states and citizens.

Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution, known as the Enumerated Powers clause, outlines specific powers of Congress, including the power to tax, regulate commerce, and provide for the common defence. Another clause in Article I, Section 8, grants Congress the power to organise and govern the Militia.

Some experts consider certain clauses in the Constitution to be odd or peculiar. For instance, a clause allowing the president to make unilateral appointments when the Senate is not in session is seen as unusual, and some presidents have used it to circumvent Senate confirmation for controversial appointments. Another odd clause, intended to prevent federal officers from receiving favours from foreign governments, has raised questions about its interpretation and applicability.