Political runoff, also known as a runoff election, is a voting process used in certain electoral systems to ensure a candidate achieves a majority (more than 50%) of the votes to win an election. This mechanism is typically employed when no candidate secures a majority in the initial round of voting. In a runoff, the top two candidates from the first round advance to a second, decisive election, where voters choose between them. This system is commonly used in presidential, legislative, and local elections worldwide, particularly in countries like France, Brazil, and many U.S. states, to ensure the elected official has broader public support and legitimacy. Runoffs aim to reduce the influence of vote splitting and encourage candidates to appeal to a wider electorate.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A political runoff is a second round of voting held when no candidate receives a majority (usually >50%) of the votes in the first round. |

| Purpose | To ensure the winning candidate has majority support, enhancing legitimacy. |

| Common Systems | Two-round system (used in countries like France, Brazil, and Argentina). |

| Threshold | Typically requires a candidate to secure >50% of the votes to win outright. |

| Voter Turnout | Often lower in the runoff compared to the first round due to voter fatigue. |

| Strategic Voting | Voters may shift support to more viable candidates to prevent undesired outcomes. |

| Cost | Higher for governments and political parties due to organizing two elections. |

| Examples | French presidential elections, Brazilian general elections, U.S. primary runoffs. |

| Criticisms | Can lead to polarization, higher costs, and reduced voter participation. |

| Alternatives | Instant-runoff voting (ranked-choice voting) or proportional representation systems. |

| Latest Trends | Increasing use in emerging democracies to ensure stable governance. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition: Political runoff is a second election round between top two candidates if none achieves majority

- Purpose: Ensures winner secures over 50% of votes, enhancing democratic legitimacy

- Common Systems: Used in presidential, mayoral, and parliamentary elections globally

- Pros: Reduces vote splitting, encourages candidate consensus, and clarifies voter preference

- Cons: Higher costs, lower turnout, and potential polarization in second rounds

Definition: Political runoff is a second election round between top two candidates if none achieves majority

In electoral systems, a political runoff serves as a tiebreaker when no candidate secures a majority in the initial vote. This mechanism, prevalent in countries like France and Brazil, ensures the eventual winner garners more than 50% of the votes, enhancing democratic legitimacy. For instance, in France’s 2017 presidential election, Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen advanced to the runoff after neither achieved a majority in the first round, with Macron ultimately winning 66% of the vote.

Implementing a runoff system requires clear rules to avoid ambiguity. First, define the threshold for advancing to the second round—typically the top two candidates. Second, establish a timeline for the runoff, usually 2–4 weeks after the initial election, to allow campaigns to refocus and voters to reassess. Third, ensure transparency in vote counting and candidate eligibility to maintain public trust. For example, in Georgia’s 2020 U.S. Senate races, runoffs were held in January 2021, giving candidates like Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock time to mobilize supporters effectively.

Critics argue runoffs can be costly and burdensome, requiring additional resources for administration and voter turnout. However, proponents counter that the system encourages candidates to appeal to a broader electorate in the second round, fostering coalition-building. In practice, runoff campaigns often shift focus to undecided voters or supporters of eliminated candidates. For instance, in the 2019 Istanbul mayoral runoff, Ekrem İmamoğlu secured victory by attracting voters from smaller parties, demonstrating the system’s potential to incentivize inclusivity.

A practical takeaway for voters in runoff systems is to stay informed about candidates’ second-round strategies. Since runoffs often involve polarizing choices, understanding how candidates pivot can help voters make more nuanced decisions. For election organizers, ensuring accessibility—such as extended polling hours or mail-in options—can mitigate turnout decline. Ultimately, while runoffs demand more effort, they prioritize the principle of majority rule, a cornerstone of robust democracies.

How Polite of the Church: Exploring Etiquette and Grace in Religious Spaces

You may want to see also

Purpose: Ensures winner secures over 50% of votes, enhancing democratic legitimacy

In a political runoff, the core objective is to ensure that the winning candidate secures more than 50% of the votes, a threshold that bolsters democratic legitimacy. This mechanism is particularly crucial in multi-candidate elections where no single contender achieves a majority in the initial round. By requiring a second round of voting, runoffs eliminate the possibility of a winner being elected with a mere plurality, which can undermine public trust in the outcome. For instance, in France’s presidential elections, candidates must advance to a runoff if no one secures over 50% in the first round, ensuring the eventual winner has a clear mandate from the majority of voters.

Consider the practical implications of this system. In a hypothetical election with four candidates, the leading candidate might win with only 35% of the vote, leaving 65% of the electorate unrepresented by their preferred choice. A runoff narrows the race to the top two contenders, forcing voters to consolidate their preferences. This process not only ensures the winner has majority support but also encourages candidates to appeal to a broader spectrum of voters, fostering more inclusive campaigns. For example, in Brazil’s 2022 presidential election, the runoff between Lula da Silva and Jair Bolsonaro compelled both candidates to seek alliances and adjust their messaging to attract undecided voters.

Critics argue that runoffs can be costly and time-consuming, but their democratic benefits often outweigh these drawbacks. To mitigate expenses, some jurisdictions, like Louisiana in the U.S., hold congressional and gubernatorial runoffs on the same day as general elections if no candidate achieves a majority. This approach reduces the logistical burden while maintaining the integrity of the majority-rule principle. Additionally, runoffs can increase voter engagement by giving citizens a second opportunity to influence the outcome, particularly if the initial results are close or contentious.

A comparative analysis highlights the global adoption of runoffs to strengthen democratic processes. In countries like Argentina and Ecuador, runoffs are mandatory if no candidate surpasses 40% of the vote or achieves a 10% lead over the runner-up. This variation ensures that winners not only secure a majority but also demonstrate a significant lead over their closest competitor. Such adaptations underscore the flexibility of runoffs in addressing specific electoral challenges while upholding the principle of majority rule.

In conclusion, the purpose of a political runoff is to safeguard democratic legitimacy by ensuring the winner garners over 50% of the votes. This system, while not without its challenges, provides a robust mechanism for consolidating voter preferences and fostering broader representation. By requiring candidates to appeal to a majority, runoffs strengthen the mandate of elected officials and reinforce public confidence in the democratic process. Whether in presidential elections or local races, the runoff system remains a vital tool for achieving fair and legitimate outcomes.

Palestine's Political Recognition: Global Status, Challenges, and Diplomatic Realities

You may want to see also

Common Systems: Used in presidential, mayoral, and parliamentary elections globally

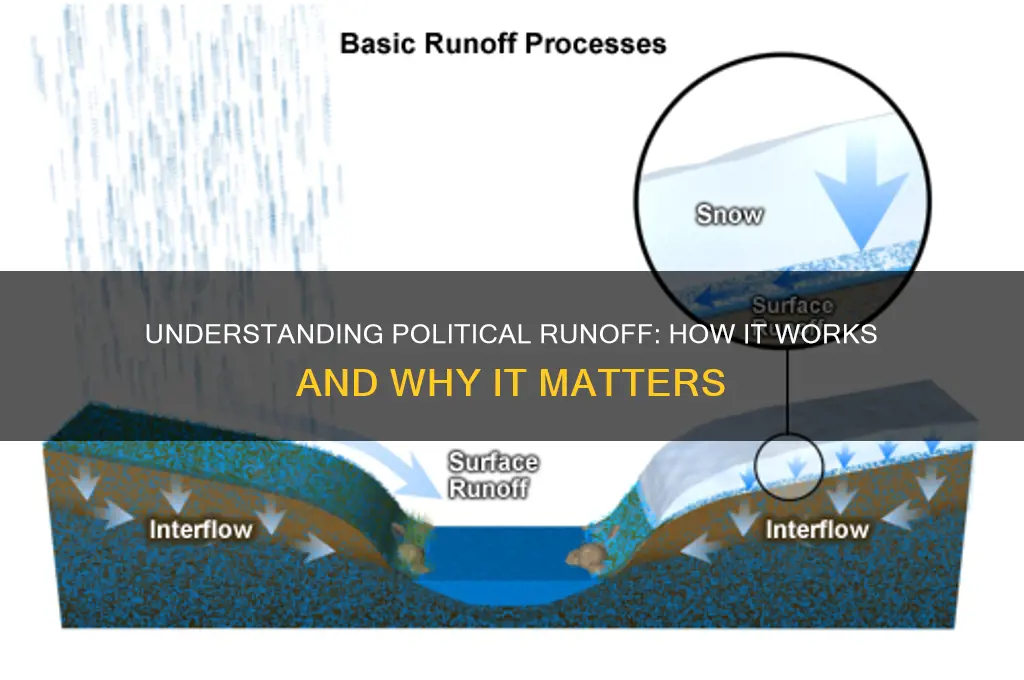

Political runoff systems are a cornerstone of democratic elections worldwide, ensuring that leaders are elected with a clear majority. Among the myriad electoral methods, three common systems stand out for their global prevalence and adaptability: the Two-Round System, Instant-Runoff Voting (IRV), and the Majority Runoff System. Each serves distinct purposes, from presidential races to local mayoral contests, and parliamentary elections, reflecting the diverse needs of democratic governance.

The Two-Round System: A Global Standard

In this system, voters cast ballots in an initial round, and if no candidate secures a majority (typically 50% +1 vote), a second round is held between the top two contenders. France’s presidential elections exemplify this approach, where candidates like Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen faced off in a decisive runoff. This method ensures the winner has broad support, though it can be costly and time-consuming. For instance, countries like Brazil and Argentina employ this system for presidential elections, balancing inclusivity with logistical challenges.

Instant-Runoff Voting (IRV): Efficiency in a Single Round

IRV, also known as ranked-choice voting, allows voters to rank candidates in order of preference. If no candidate achieves a majority, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, and their votes are redistributed to the remaining candidates based on second preferences. Australia’s House of Representatives uses IRV, ensuring a majority winner without a second round. This system is increasingly popular in U.S. mayoral elections, such as in San Francisco and New York City, where it reduces the need for costly runoffs and encourages candidates to appeal to a broader electorate.

Majority Runoff System: Tailored for Parliamentary Contexts

In parliamentary systems, the Majority Runoff System is often employed to elect representatives in single-member districts. Voters select their preferred candidate, and if no one secures a majority, a runoff is held between the top contenders. This system is prevalent in countries like the United Kingdom for local elections and in India’s Lok Sabha polls. It ensures that elected officials have a clear mandate, though it can lead to polarized campaigns in the runoff phase.

Practical Considerations and Trade-offs

Choosing the right runoff system depends on a nation’s political culture, resources, and goals. The Two-Round System prioritizes broad legitimacy but demands significant time and funding. IRV streamlines the process but requires voter education on ranking preferences. The Majority Runoff System aligns well with parliamentary structures but may exacerbate political divisions. For instance, implementing IRV in a mayoral election might increase voter engagement, while the Two-Round System could be more suitable for high-stakes presidential races.

A Global Mosaic of Democratic Practice

From the presidential palaces of Europe to the parliamentary halls of Asia, runoff systems shape how leaders are chosen. Each method reflects a unique balance between ensuring majority rule and maintaining electoral efficiency. As democracies evolve, so too will these systems, adapting to new challenges and opportunities in the pursuit of fair and representative governance.

Pink Panther's Political Satire: A Subtle Critique of Society?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Pros: Reduces vote splitting, encourages candidate consensus, and clarifies voter preference

In a political runoff, the initial election often serves as a free-for-all, where multiple candidates vie for the same voter base, leading to vote splitting. This phenomenon occurs when similar candidates divide the electorate, allowing a less-preferred candidate to win with a plurality rather than a majority. Runoff elections address this issue by advancing only the top two candidates to a second round, ensuring the eventual winner secures a majority of the votes. For instance, in the 2020 Georgia Senate runoff, Raphael Warnock’s victory over Kelly Loeffler demonstrated how a runoff can consolidate support behind a single candidate, preventing vote splitting and producing a more representative outcome.

Encouraging candidate consensus is another critical advantage of runoff elections. Knowing a second round is possible, candidates often moderate their positions to appeal to a broader electorate, fostering cooperation and reducing polarization. This dynamic was evident in France’s 2017 presidential runoff, where Emmanuel Macron’s centrist platform attracted voters from both the left and right, defeating Marine Le Pen’s more extreme agenda. Such strategic adjustments not only strengthen democratic discourse but also encourage candidates to prioritize policies with wider appeal, ultimately benefiting the electorate.

Clarifying voter preference is perhaps the most straightforward benefit of runoffs. By narrowing the field to two candidates, voters can make a direct comparison, free from the noise of a crowded initial ballot. This clarity was particularly evident in the 2018 Mali presidential runoff, where Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta’s victory over Soumaïla Cissé reflected a clear mandate from the electorate. Without a runoff, the initial results might have been ambiguous, leaving room for doubt about the true will of the voters. This process ensures that the winning candidate has undeniable legitimacy, reinforcing public trust in the electoral system.

To maximize these benefits, implementing runoffs requires careful consideration. For example, setting a threshold for the first round—such as requiring a candidate to secure 40% of the vote to avoid a runoff—can streamline the process. Additionally, voter education campaigns are essential to ensure participation remains high in the second round. Countries like Brazil and Argentina have successfully integrated runoffs into their electoral systems, proving that with proper planning, this mechanism can reduce vote splitting, foster candidate consensus, and deliver a clearer voter mandate. Adopting such a system could be a transformative step for democracies seeking to enhance the fairness and effectiveness of their elections.

Gracefully Declining Payment: A Guide to Polite Refusal Strategies

You may want to see also

Cons: Higher costs, lower turnout, and potential polarization in second rounds

Runoff elections, while designed to ensure a majority winner, often come with a hefty price tag. The financial burden of organizing a second round of voting can strain already tight budgets. Consider the 2020 Georgia Senate runoffs in the U.S., which cost an estimated $20 million more than a typical election. This includes expenses for polling stations, staff, and security, all of which must be duplicated for the second round. For cash-strapped regions, this additional cost can divert funds from essential public services like education or healthcare, raising questions about the allocation of resources in the democratic process.

Beyond the financial implications, runoffs frequently suffer from lower voter turnout, undermining their intended purpose. In the 2017 French legislative runoffs, turnout dropped from 48.7% in the first round to just 42.6% in the second. This decline is often attributed to voter fatigue, disillusionment, or the perception that the outcome is already decided. Lower turnout can skew results, as the second round may disproportionately represent more motivated or extreme segments of the electorate, rather than the broader population. This raises concerns about the legitimacy of the final result, as it may not truly reflect the will of the majority.

Perhaps the most troubling consequence of runoffs is their potential to exacerbate political polarization. In the second round, voters are typically forced to choose between two candidates who represent the extremes of the political spectrum, as moderate candidates are often eliminated in the first round. This dynamic was evident in the 2017 Austrian presidential runoff, where the race narrowed to a far-right candidate and a Green Party candidate. Such polarization can deepen societal divisions, as voters are pushed into camps with starkly opposing ideologies, making compromise and unity more difficult in the aftermath of the election.

To mitigate these drawbacks, policymakers could explore alternative voting systems, such as ranked-choice voting, which eliminates the need for a second round by allowing voters to rank candidates in order of preference. This approach not only reduces costs but also encourages candidates to appeal to a broader electorate, potentially dampening polarization. For regions committed to runoffs, targeted measures like public awareness campaigns or making voting more accessible (e.g., extending polling hours or expanding mail-in options) could help counteract declining turnout. Ultimately, while runoffs aim to strengthen democracy, their implementation requires careful consideration of these unintended consequences.

Are Americans More Polite? Exploring Cultural Etiquette and Social Norms

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political runoff is a second round of voting held when no candidate in the initial election receives a majority (more than 50%) of the votes. It typically occurs between the top two candidates from the first round.

Political runoffs are necessary to ensure the winning candidate has a clear majority of voter support, especially in elections with multiple candidates where no one achieves a majority in the first round.

Countries like France, Brazil, and many African nations commonly use runoff voting systems, particularly in presidential elections, to ensure the winner has broad voter approval.

A runoff election is a second round of voting between the top candidates from the first round, while a primary election is an earlier stage where voters within a political party choose their candidate for the general election.

Low voter turnout in a runoff can affect the outcome, as a smaller group of voters may determine the winner. This can lead to results that may not fully represent the broader electorate's preferences.