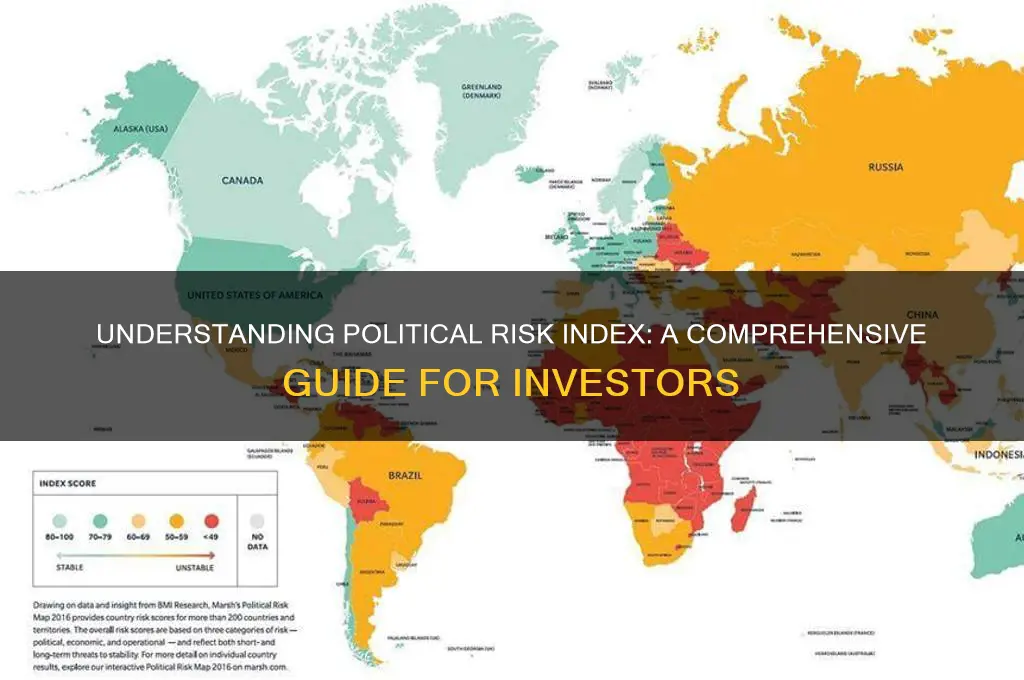

The Political Risk Index (PRI) is a quantitative tool used by investors, businesses, and policymakers to assess and compare the political risks associated with operating in different countries. It evaluates factors such as political stability, governance quality, regulatory environment, and the likelihood of events like coups, civil unrest, or policy shifts that could impact economic activities. By aggregating data from various indicators, the PRI provides a standardized score or ranking, enabling stakeholders to make informed decisions about market entry, investment strategies, and risk mitigation. Understanding the PRI is crucial for navigating the complexities of global markets, as political risks can significantly influence economic outcomes and the security of international ventures.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Purpose: Understanding political risk index as a tool for assessing country-specific risks

- Key Components: Factors like governance, stability, policy, and socio-economic conditions included in the index

- Calculation Methods: How data is collected, weighted, and aggregated to create the index

- Applications in Business: Use by investors and companies for decision-making in global markets

- Limitations and Criticisms: Challenges in accuracy, subjectivity, and dynamic political environments affecting reliability

Definition and Purpose: Understanding political risk index as a tool for assessing country-specific risks

Political risk index (PRI) is a quantitative measure designed to evaluate the likelihood and potential impact of political events on a country’s business environment, investment climate, and economic stability. Unlike broad risk assessments, PRI focuses on country-specific factors such as government stability, regulatory changes, corruption levels, and geopolitical tensions. Its primary purpose is to provide investors, multinational corporations, and policymakers with a structured framework to anticipate and mitigate risks tied to political volatility. For instance, a high PRI score for a country might signal frequent policy shifts, civil unrest, or weak rule of law, prompting stakeholders to adjust strategies or allocate resources cautiously.

To construct a PRI, analysts typically aggregate data from diverse sources, including economic indicators, news sentiment, and expert surveys. Key components often include measures of political violence, expropriation risk, and the quality of governance. For example, the PRS Group’s International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) uses a 12-point scale to assess risks like government stability and law and order. Similarly, Eurasia Group’s Global Political Risk Index ranks countries based on factors like populism, technological disruption, and U.S.-China tensions. These indices are not one-size-fits-all; they are tailored to reflect the unique political landscape of each nation, ensuring relevance across industries and investment horizons.

The utility of PRI extends beyond mere risk identification—it serves as a decision-making tool. For multinational corporations, a high PRI might prompt the diversification of supply chains or the adoption of political risk insurance. Investors might use PRI to weigh the potential returns of emerging markets against their volatility. Policymakers, on the other hand, can leverage PRI to design foreign aid programs or diplomatic strategies that account for recipient countries’ political fragility. For instance, a country with a PRI indicating high corruption levels might require stricter compliance measures in aid agreements.

However, interpreting PRI requires caution. While it provides a snapshot of political risk, it is not infallible. Indices rely on historical data and assumptions that may not predict sudden events like coups or elections. Additionally, PRI often lacks granularity, grouping diverse risks under broad categories like “governance” or “stability.” Users must supplement PRI with qualitative analysis, such as local expertise or scenario planning, to avoid oversimplification. For example, a country with moderate PRI might still face sector-specific risks, such as resource nationalism in mining industries, which PRI alone cannot capture.

In practice, PRI is most effective when integrated into a broader risk management strategy. Companies might use PRI to prioritize countries for market entry, while investors could combine it with financial metrics to assess risk-adjusted returns. For instance, a tech firm considering expansion into Southeast Asia might cross-reference PRI scores with local data on digital infrastructure and consumer behavior. Similarly, a sovereign wealth fund might use PRI to stress-test its portfolio against geopolitical shocks. By treating PRI as one tool among many, stakeholders can navigate political uncertainties with greater precision and confidence.

Mastering Polite Salary Negotiation: Strategies for a Win-Win Outcome

You may want to see also

Key Components: Factors like governance, stability, policy, and socio-economic conditions included in the index

Governance stands as the backbone of any political risk index, serving as a critical indicator of a country’s ability to manage public affairs and resources effectively. It encompasses the quality of institutions, rule of law, and the transparency of decision-making processes. For instance, a nation with robust anti-corruption measures and an independent judiciary will score higher on governance metrics, signaling lower political risk for investors. Conversely, weak governance, marked by bureaucratic inefficiency or widespread corruption, can deter foreign investment and destabilize economic growth. Assessing governance involves analyzing factors like regulatory consistency, public sector accountability, and the enforcement of contracts, which collectively shape the predictability of a country’s political environment.

Stability, another cornerstone of the political risk index, refers to the resilience of a country’s political system against internal and external shocks. This includes the frequency of political violence, the legitimacy of leadership, and the cohesion of governing coalitions. For example, countries with a history of frequent coups or civil unrest will rank poorly in stability assessments, posing higher risks for businesses operating within their borders. Stability is not merely the absence of conflict but also the presence of mechanisms to manage dissent and ensure peaceful transitions of power. Investors often scrutinize indicators like election integrity, military influence in politics, and the prevalence of social unrest to gauge a country’s stability quotient.

Policy consistency and predictability are vital components that directly impact a country’s political risk profile. Sudden shifts in economic, trade, or regulatory policies can unsettle markets and erode investor confidence. For instance, a government that frequently alters tax laws or imposes arbitrary restrictions on foreign businesses creates an environment of uncertainty. Conversely, countries with clear, long-term policy frameworks—such as those supporting free trade or foreign direct investment—tend to attract more capital. Analyzing policy risk involves examining the ideological orientation of ruling parties, the frequency of policy reversals, and the alignment of domestic policies with international norms.

Socio-economic conditions provide the contextual backdrop against which political risks are assessed. High levels of inequality, unemployment, or poverty can fuel social discontent and political instability. For example, a country with a large youth population facing limited economic opportunities may be more prone to protests or civil unrest. Similarly, regions with significant ethnic, religious, or regional divides often exhibit higher political risks due to the potential for conflict. Metrics like income distribution, education levels, and access to basic services are crucial in evaluating socio-economic conditions. Investors must consider these factors to understand the underlying pressures that could trigger political upheaval.

Incorporating these components—governance, stability, policy, and socio-economic conditions—into a political risk index provides a holistic view of a country’s investment climate. Each factor interacts dynamically, influencing the overall risk landscape. For instance, strong governance can mitigate the impact of socio-economic challenges, while policy unpredictability can exacerbate stability issues. By systematically analyzing these elements, stakeholders can make informed decisions, balancing potential rewards against the risks inherent in operating within a particular political environment. This nuanced approach ensures that the index serves as a practical tool for navigating the complexities of global markets.

Mastering the Art of Polite RSVP: Etiquette Tips for Every Occasion

You may want to see also

Calculation Methods: How data is collected, weighted, and aggregated to create the index

Data collection for political risk indices begins with identifying key indicators that reflect a country's political stability, governance quality, and potential for disruption. These indicators often include measures of government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, political violence, and corruption. Sources range from international organizations like the World Bank and Transparency International to local think tanks, media outlets, and expert surveys. For instance, the World Bank's Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) provides data on six dimensions of governance, while the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) relies on country analysts and proprietary models. The diversity of sources ensures a multifaceted view, though it also introduces variability in data quality and timeliness.

Once data is gathered, weighting becomes critical to reflect the relative importance of each indicator. Not all factors carry the same risk implications; for example, political violence may be weighted more heavily than bureaucratic efficiency in predicting short-term instability. Weighting schemes are often based on theoretical frameworks, historical correlations, or expert judgment. The PRS Group’s International Country Risk Guide (ICRG), for instance, assigns higher weights to indicators like government stability and socioeconomic conditions. Transparency in weighting is essential, as it allows users to understand the index’s biases and limitations. However, proprietary indices often keep their weighting formulas confidential, limiting external scrutiny.

Aggregation transforms raw data into a single, comparable score. Common methods include linear transformations, where each indicator is normalized and summed, or more complex techniques like principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce dimensionality. The EIU’s Democracy Index, for example, aggregates five categories (electoral process, civil liberties, etc.) into a 0–10 scale. Aggregation must balance simplicity with nuance; overly complex methods may obscure interpretability, while simplistic approaches risk oversimplifying reality. Standardization ensures comparability across countries and time, but it also requires careful handling of missing data and outliers.

Practical challenges abound in this process. Data gaps, especially in less transparent or conflict-prone regions, can skew results. Subjectivity in expert assessments introduces another layer of uncertainty. For instance, perceptions of corruption can vary widely depending on cultural norms or political biases. To mitigate these issues, some indices incorporate cross-validation, where multiple sources are compared to ensure consistency. Users should critically evaluate the methodology, considering the index’s intended purpose and potential blind spots. For businesses or investors, understanding these nuances is key to interpreting the index effectively and making informed decisions.

Finally, the dynamic nature of political risk demands regular updates and revisions. Indices like the Fragile States Index (FSI) are updated annually, while others may adjust more frequently in response to acute events. However, frequent updates can introduce volatility, making it harder to track long-term trends. Striking a balance between timeliness and stability is crucial. Users should also consider the index’s historical performance—how well it predicted past crises—to gauge its reliability. Ultimately, a political risk index is a tool, not a crystal ball, and its value lies in its ability to systematize complex information rather than provide definitive answers.

Capitalizing Political Ideologies: Rules, Exceptions, and Common Mistakes Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Applications in Business: Use by investors and companies for decision-making in global markets

In the realm of global business, the Political Risk Index (PRI) serves as a critical tool for investors and companies navigating the complexities of international markets. By quantifying the likelihood of political events disrupting operations, investments, or supply chains, the PRI enables stakeholders to make informed decisions. For instance, a multinational corporation considering expansion into a new country might use the PRI to assess the stability of the local government, the risk of regulatory changes, or the potential for civil unrest. This data-driven approach helps prioritize markets with lower political risks, ensuring strategic alignment with long-term business goals.

Investors, particularly those in emerging markets, rely on the PRI to mitigate uncertainty. A high PRI score in a country like Venezuela, for example, signals elevated risks due to political instability, currency controls, and expropriation threats. Conversely, a low PRI score in Singapore highlights its stable political environment and robust legal framework, making it an attractive destination for foreign direct investment. By integrating PRI data into portfolio analysis, investors can diversify risk and allocate capital more effectively. Tools like Euromoney’s Country Risk Survey or the PRS Group’s International Country Risk Guide provide granular insights, allowing investors to compare countries side by side and make data-backed decisions.

Companies operating globally also use the PRI to safeguard their supply chains. For example, a tech firm sourcing rare earth minerals from a politically volatile region might leverage PRI data to identify alternative suppliers in more stable countries. Similarly, a pharmaceutical company expanding into new markets could use the PRI to evaluate the risk of policy shifts affecting drug pricing or intellectual property rights. By incorporating PRI metrics into risk management frameworks, businesses can develop contingency plans, such as dual-sourcing strategies or political risk insurance, to minimize disruptions.

However, the PRI is not without limitations. Its effectiveness depends on the quality and timeliness of the data, as well as the methodology used to calculate it. Companies must complement PRI analysis with on-the-ground intelligence and scenario planning to account for unforeseen events. For instance, while a country may have a low PRI score, sudden geopolitical tensions or leadership changes could alter its risk profile rapidly. Therefore, businesses should treat the PRI as one of several tools in their decision-making arsenal, not a standalone solution.

In conclusion, the Political Risk Index is an indispensable resource for investors and companies operating in global markets. By providing a structured framework to assess political risks, it empowers stakeholders to make strategic decisions with greater confidence. Whether evaluating investment opportunities, expanding into new markets, or securing supply chains, the PRI offers actionable insights that drive business success in an increasingly interconnected world.

Mastering Polite Responses: A Guide to Answering Questions Gracefully

You may want to see also

Limitations and Criticisms: Challenges in accuracy, subjectivity, and dynamic political environments affecting reliability

Political risk indices, while invaluable for investors and policymakers, face inherent limitations that undermine their reliability. One critical challenge is the subjectivity embedded in their construction. Most indices rely on expert opinions, surveys, or qualitative assessments, which can vary widely based on the biases, experiences, or methodologies of the evaluators. For instance, what one analyst considers a "high risk" political event might be deemed moderate by another, leading to inconsistencies. This subjectivity is further compounded when indices incorporate indicators like "government stability" or "rule of law," which lack universally agreed-upon definitions or measurement standards. Without objective, quantifiable metrics, these indices risk becoming reflections of personal or institutional biases rather than accurate risk assessments.

Another limitation lies in the static nature of many political risk indices, which struggle to capture the dynamic and often unpredictable shifts in political environments. Political landscapes can change rapidly—a coup, election, or policy reversal can alter risk profiles overnight. Yet, many indices are updated annually or quarterly, leaving users with outdated information during critical periods. For example, an index published in January might not account for a sudden protest movement in March, rendering its predictions obsolete. Real-time monitoring and frequent updates are resource-intensive, and the trade-off between timeliness and feasibility often results in a lag that diminishes the index’s utility in fast-evolving scenarios.

The accuracy of political risk indices is also constrained by the complexity of the variables they attempt to measure. Political risk is multifaceted, encompassing factors like regulatory changes, corruption, geopolitical tensions, and social unrest. Quantifying these elements often requires simplifying assumptions that may overlook critical nuances. For instance, an index might score a country highly on "regulatory quality" based on formal laws, but fail to account for informal practices or enforcement gaps that significantly impact business operations. This oversimplification can lead to misleading conclusions, particularly in countries where formal institutions and informal realities diverge sharply.

Finally, the reliability of political risk indices is often questioned due to their one-size-fits-all approach, which fails to account for sector-specific or investor-specific vulnerabilities. A mining company, for example, faces different political risks (e.g., resource nationalism) than a tech firm (e.g., data privacy regulations). Yet, most indices provide a single country-level score, offering little guidance on how risks vary across industries or investment types. This lack of granularity limits their practical application, forcing users to either supplement the index with additional research or accept a generalized assessment that may not align with their specific exposure.

To mitigate these challenges, users should treat political risk indices as starting points rather than definitive tools. Cross-referencing multiple indices, incorporating real-time data sources, and conducting on-the-ground due diligence can enhance accuracy and reliability. Additionally, recognizing the inherent subjectivity and limitations of these indices fosters a more nuanced understanding of political risk, enabling better-informed decision-making in an increasingly volatile global landscape.

Automation's Political Revolution: Transforming Governance, Campaigns, and Public Policy

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A Political Risk Index is a quantitative tool used to measure and assess the level of political risk in a country. It evaluates factors such as political stability, governance, regulatory environment, and potential for social unrest to help investors and businesses make informed decisions.

The Political Risk Index is calculated using a combination of qualitative and quantitative data. It typically includes indicators like government effectiveness, corruption levels, rule of law, political violence, and macroeconomic stability, often weighted and aggregated into a single score.

The Political Risk Index is used by multinational corporations, investors, financial institutions, governments, and researchers to assess the risks associated with operating or investing in a particular country.

Common factors include political stability, regulatory quality, corruption perception, security risks, legal frameworks, and the likelihood of government intervention or policy changes that could impact business operations.

While other risk indices may focus on economic, financial, or operational risks, the Political Risk Index specifically evaluates risks arising from political factors, such as government actions, social unrest, or changes in political leadership.