Political salt refers to the strategic use of seemingly minor or symbolic actions, policies, or statements by governments, organizations, or individuals to exert influence, convey messages, or achieve broader political objectives. Unlike overt diplomatic or military maneuvers, political salt operates subtly, often leveraging cultural, economic, or social nuances to shape public opinion, pressure adversaries, or solidify alliances. Examples include targeted sanctions, symbolic gestures, or carefully crafted rhetoric designed to create ripple effects without escalating conflicts directly. This concept highlights the intricate and often covert ways in which power is wielded in modern politics, emphasizing the importance of nuance and context in understanding global and local political dynamics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A term used to describe the strategic use of salt as a political tool, often involving its production, distribution, or taxation to exert control, influence, or punishment. |

| Historical Examples | - Ancient Rome: Salt tax (salarium) was a significant source of revenue, and soldiers were sometimes paid in salt. - India under British Rule: Salt tax and monopoly led to the famous Salt March led by Mahatma Gandhi in 1930. - France: Gabelle, a regressive salt tax, was a major grievance leading up to the French Revolution. |

| Modern Relevance | - Economic Control: Governments may use salt production and distribution to regulate markets or generate revenue. - Geopolitical Leverage: Salt, as a vital resource, can be used in trade negotiations or sanctions. - Environmental Policy: Regulations on salt mining or use (e.g., road de-icing) can have political implications. |

| Symbolism | Salt often symbolizes value, preservation, and essentialness, making its control a powerful political statement. |

| Current Issues | - Salt Mining Disputes: Conflicts over salt resources in regions like the Dead Sea or the Himalayas. - Health Policies: Taxation or regulation of high-salt foods as part of public health initiatives. |

| Cultural Impact | Salt has cultural significance in many societies, and its political manipulation can provoke strong public reactions. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Historical Origins: Salt's role in ancient economies, taxation, and its impact on political power

- Salt Taxation: How salt taxes shaped governments, revolts, and economic policies globally

- Salt as Currency: Use of salt as a medium of exchange in early civilizations

- Salt and Colonialism: European colonial powers' control of salt trade and resources

- Modern Political Significance: Salt's role in contemporary politics, trade, and geopolitical strategies

Historical Origins: Salt's role in ancient economies, taxation, and its impact on political power

Salt, a seemingly mundane mineral, held extraordinary power in ancient economies, shaping trade routes, taxation systems, and the very fabric of political authority. Its scarcity and essential role in food preservation made it a coveted commodity, often referred to as "white gold." In ancient Rome, for instance, soldiers were partially paid in salt, a practice that gave rise to the word "salary," derived from the Latin word for salt, *sal*. This simple mineral was not just a seasoning; it was a currency, a symbol of wealth, and a tool of control.

Consider the Salt Road in sub-Saharan Africa, where caravans transported salt across vast deserts, bartering it for gold ounce for ounce. This trade route not only facilitated economic exchange but also cemented political alliances and dependencies. Rulers who controlled salt production or trade routes wielded immense power, using it to enrich their coffers or punish rivals. In ancient China, the state monopoly on salt, known as the *Salt Gabelle*, became a cornerstone of imperial revenue, funding wars and public works. However, this monopoly also sparked rebellions, as heavy salt taxes burdened the common people, illustrating the double-edged sword of salt’s political influence.

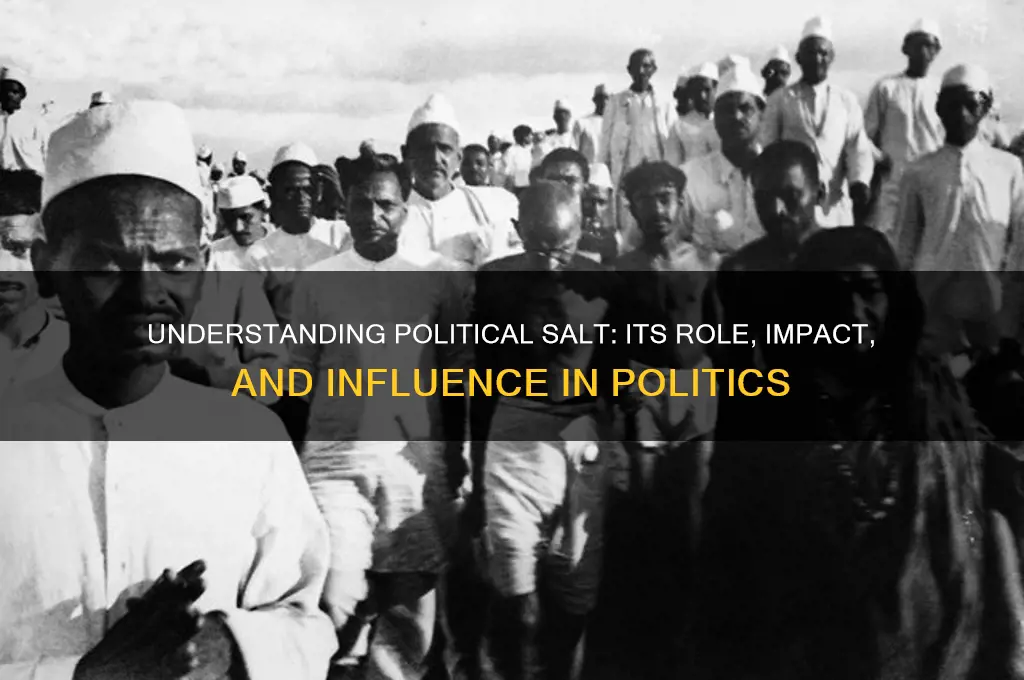

To understand salt’s impact on taxation, examine the French *Gabelle*, a salt tax that divided the country into regions with varying tax rates, creating widespread discontent. The tax was so despised that it became a rallying cry during the French Revolution, symbolizing the arbitrary and oppressive nature of the monarchy. Similarly, in India, the British salt tax under colonial rule led to Mahatma Gandhi’s iconic Salt March in 1930, a pivotal act of civil disobedience that galvanized the independence movement. These examples highlight how salt taxation could either stabilize or destabilize political regimes, depending on its implementation and perception.

Practical tip: When studying ancient economies, trace the salt trade to uncover hidden power dynamics. For instance, analyze trade records or archaeological findings of salt ingots to map political influence. Caution: Avoid oversimplifying salt’s role; its impact varied by region, culture, and era. For example, while salt was a luxury in landlocked areas, coastal communities often had easier access, reducing its political significance.

In conclusion, salt’s historical role in economies and taxation reveals its profound impact on political power. From Roman salaries to Chinese monopolies and revolutionary protests, salt was more than a commodity—it was a catalyst for change, a measure of control, and a mirror of societal inequities. By examining its history, we gain insight into how even the smallest resources can shape the course of civilizations.

Trump's Legacy: The End of Political Comedy as We Knew It

You may want to see also

Salt Taxation: How salt taxes shaped governments, revolts, and economic policies globally

Salt, an essential mineral for human survival, has historically been a powerful tool for governments to exert control and generate revenue. The taxation of salt, often referred to as the "white gold," has left an indelible mark on global history, sparking revolts, shaping economic policies, and even influencing the rise and fall of empires. From ancient China to colonial India, salt taxes have been a catalyst for social and political change, demonstrating the profound impact of this seemingly mundane commodity on the course of human events.

Consider the case of ancient China, where the state monopoly on salt production and distribution dates back to the 3rd century BCE. The Chinese government, recognizing the strategic importance of salt, imposed heavy taxes on its sale, using the revenue to fund public works, military campaigns, and administrative expenses. This system, known as the "salt gabelle," was so effective that it became a model for other governments to follow. In France, for instance, the salt tax, or "gabelle," was a major source of revenue for the monarchy, with regional variations in tax rates leading to widespread discontent and, ultimately, contributing to the outbreak of the French Revolution. The infamous "Salt March" led by Mahatma Gandhi in 1930, protesting British salt taxes in India, further illustrates the power of salt taxation to galvanize public opinion and fuel nationalist movements.

To understand the mechanics of salt taxation, let's examine the British salt tax in India, which was imposed in 1882. The tax, set at 2 rupees per maund (approximately 37 kilograms), was a significant burden on the local population, who relied heavily on salt for their daily needs. The British government, however, saw salt as a lucrative source of revenue, generating over 15 million rupees annually by the early 20th century. To evade the tax, many Indians began producing salt illegally, leading to a cat-and-mouse game between the authorities and smugglers. This situation ultimately culminated in Gandhi's Salt March, which not only challenged British authority but also highlighted the absurdity and injustice of the salt tax.

A comparative analysis of salt taxation policies reveals interesting patterns and trends. In countries like Japan and the United States, salt taxes were relatively low or non-existent, allowing for a more free and competitive market. In contrast, countries with high salt taxes, such as France and India, experienced significant social and political unrest. The takeaway here is that salt taxation, when imposed excessively or unfairly, can have severe consequences, including economic distortions, black markets, and public discontent. To mitigate these risks, governments should consider implementing salt taxation policies that balance revenue generation with social equity and public health concerns.

In designing salt taxation policies, policymakers should follow a set of best practices. First, taxes should be set at a level that discourages excessive consumption without being prohibitively expensive. A tax rate of 1-2% of the retail price, for example, could generate revenue while minimizing the impact on low-income households. Second, governments should consider providing targeted subsidies or exemptions for vulnerable populations, such as the elderly or those with specific medical conditions. Finally, salt taxation policies should be part of a broader public health strategy, which includes education campaigns, product labeling, and incentives for reduced salt consumption. By adopting a nuanced and evidence-based approach, governments can harness the potential of salt taxation to promote public health, generate revenue, and foster social stability.

Politeness Matters: Why Being Courteous is Always in Style

You may want to see also

Salt as Currency: Use of salt as a medium of exchange in early civilizations

Salt, a humble mineral, once held the power to shape economies and influence the rise and fall of civilizations. Its role as a medium of exchange in early societies is a fascinating chapter in the history of currency, one that challenges our modern understanding of value and trade. In ancient times, salt was not just a seasoning but a precious commodity, often worth its weight in gold, and its impact on political and economic systems was profound.

The Value of Salt in Ancient Times

Imagine a world where a pinch of salt could buy you a day's labor or a small bag could secure a bride. This was the reality in many early civilizations, where salt's value was unparalleled. The ancient Romans, for instance, valued salt so highly that they established a system of salt rations for their soldiers, known as 'salarium'—a term that evolved into the modern word 'salary'. This practice highlights the direct link between salt and economic compensation. In sub-Saharan Africa, salt was a crucial trade item, with the Tuareg people of the Sahara desert using it as a form of currency, often in the form of salt slabs or cakes. These examples illustrate how salt's scarcity and essential nature made it a powerful medium of exchange, facilitating trade and economic growth.

A Medium of Exchange and a Political Tool

The use of salt as currency was not merely a practical solution for barter systems; it had significant political implications. Governments and rulers quickly recognized the potential of controlling salt production and distribution. In ancient China, the state-controlled salt monopoly, known as the 'Salt Gabelle', was a powerful tool for generating revenue and maintaining control. The Chinese government imposed heavy taxes on salt, making it a lucrative source of income and a means to fund military campaigns and public works. Similarly, in medieval Europe, salt taxes became a contentious issue, leading to protests and even revolutions, as seen in the 'Salt March' led by Mahatma Gandhi in colonial India, which was a pivotal moment in the Indian independence movement.

The Logistics of Salt Trade

Trading salt presented unique challenges and opportunities. Its durability and long shelf life made it an ideal commodity for long-distance trade. Caravans carried salt across deserts and mountains, establishing trade routes that connected distant civilizations. The famous Salt Road in Europe, for instance, linked the salt mines of Salzburg to the Mediterranean, fostering cultural exchange and economic interdependence. However, the process was not without risks. Salt's value attracted thieves and bandits, and its transportation required careful planning and protection. Merchants had to navigate not only physical obstacles but also political ones, as they often needed permits and had to pay tolls to local rulers.

A Legacy in Modern Times

The legacy of salt as currency can still be traced in modern language and culture. The word 'salary' is a constant reminder of its historical value. In some parts of the world, salt-related idioms and expressions persist, such as 'worth one's salt', meaning to be competent or worthy. Moreover, the concept of salt taxes and monopolies has left an indelible mark on economic policies. Many countries have, at some point, implemented salt taxes or subsidies, recognizing its strategic importance. Today, while salt is no longer a primary medium of exchange, its historical role serves as a fascinating study in the evolution of currency and the intricate relationship between resources, trade, and political power.

In exploring the use of salt as currency, we uncover a rich narrative of human ingenuity, economic adaptation, and political strategy. It invites us to reconsider the arbitrary nature of value and the potential for everyday resources to shape the course of history. This ancient practice offers a unique lens through which to understand the complexities of early civilizations and their enduring impact on our modern world.

Mastering Polite Requests: A Guide to Asking Graciously and Effectively

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Salt and Colonialism: European colonial powers' control of salt trade and resources

Salt, a seemingly mundane mineral, was once a cornerstone of global economies and a potent tool of colonial control. European powers recognized its indispensability—preserving food, seasoning meals, and even de-icing roads—and leveraged this to consolidate their dominance. The British, for instance, monopolized salt production in India through the Salt Act of 1882, forcing locals to buy heavily taxed salt from the colonial government. This stranglehold on a basic necessity fueled widespread discontent, culminating in Mahatma Gandhi’s iconic Salt March in 1930, a pivotal moment in India’s independence movement.

The French, too, exploited salt’s strategic value in their colonies. In West Africa, they imposed the *impôt de capitation*, a head tax often paid in salt, effectively controlling both the resource and the local economy. This system not only enriched the colonizers but also disrupted traditional trade networks, leaving indigenous communities dependent on European supply chains. Salt, in this context, became a symbol of oppression, its grains weighing heavier than their modest size suggested.

To understand the mechanics of this control, consider the process of salt extraction and distribution. Colonial powers often nationalized salt pans, evicting local producers and centralizing production. In the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia), the Dutch East India Company established a monopoly over salt, exporting it to other colonies while restricting local access. This dual strategy—exploiting resources for profit and withholding them for control—exemplifies how salt became a political weapon.

A comparative analysis reveals that salt’s role in colonialism was not merely economic but deeply psychological. By controlling salt, colonizers dictated the rhythms of daily life, from food preparation to religious rituals. In many cultures, salt held spiritual significance, making its monopolization a form of cultural erasure. For instance, in parts of Africa, salt was used in ceremonies to ward off evil spirits, a practice undermined by colonial restrictions.

Practical resistance to this control emerged in various forms. Smuggling became a common act of defiance, with clandestine networks emerging to bypass colonial taxes. In India, villagers secretly produced salt from seawater, risking severe penalties. These acts of resilience highlight the human ingenuity that countered colonial exploitation. Today, studying these histories offers a lens into the intersection of resource politics and power dynamics, reminding us that even the smallest grains can carry the weight of empires.

Understanding the Political Spectrum: A Comprehensive Guide to Ideologies

You may want to see also

Modern Political Significance: Salt's role in contemporary politics, trade, and geopolitical strategies

Salt, once a cornerstone of ancient economies and a catalyst for wars, remains a potent symbol and strategic resource in modern geopolitics. Its contemporary role extends beyond seasoning, embedding itself in trade agreements, environmental policies, and even diplomatic tensions. Consider the Dead Sea, a natural reservoir of minerals, where Israel and Jordan’s joint venture to extract potash—a salt derivative critical for fertilizers—highlights how salt-related resources can foster cooperation or competition. This example underscores salt’s dual nature: a bridge for economic alliances and a flashpoint for resource disputes.

In trade, salt’s derivatives, such as sodium chloride and magnesium chloride, are indispensable for industries ranging from pharmaceuticals to renewable energy. Lithium extraction from brine pools, essential for electric vehicle batteries, has become a geopolitical chess piece. Countries like Chile and Argentina are leveraging their salt flat reserves to dominate the green energy market, while China’s control over rare earth processing gives it a strategic edge. Here, salt is not just a commodity but a lever in the global shift toward sustainability, with nations jockeying for dominance in this emerging economy.

Environmental policies further amplify salt’s political significance. Road de-icing salts, while crucial for public safety, contribute to freshwater contamination and soil degradation. In the U.S., states like Minnesota are reevaluating salt usage, balancing infrastructure needs with ecological preservation. This dilemma illustrates how salt’s practical applications intersect with political decision-making, forcing governments to weigh short-term benefits against long-term environmental costs.

Finally, salt’s symbolic value persists in diplomatic gestures and cultural narratives. India’s historic Salt March, led by Gandhi, remains a blueprint for nonviolent resistance, inspiring movements worldwide. Today, nations may use salt-related projects—such as desalination plants in water-scarce regions—as tools of soft power, showcasing technological prowess and humanitarian aid. In this light, salt transcends its material utility, becoming a medium for political messaging and global influence.

In sum, salt’s modern political significance lies in its ability to shape trade dynamics, environmental policies, and diplomatic strategies. From lithium-rich brine pools to de-icing debates, its derivatives and applications are central to contemporary challenges. As nations navigate resource competition and sustainability, salt’s role will only grow, demanding innovative governance and international cooperation. Its legacy as a political catalyst endures, evolving with the complexities of the 21st century.

How Domestic Political Institutions Shape Global IMO Policies and Outcomes

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political salt refers to the metaphorical use of "salt" in political contexts, symbolizing influence, preservation, or disruption. It can represent a small but significant factor that shapes political outcomes or strategies.

The term draws from historical and cultural references, such as the phrase "worth one's salt" (meaning to be competent) or the idea of salt as a preservative or irritant, which has been adapted to describe subtle yet impactful political actions or elements.

In modern politics, "political salt" can describe strategic maneuvers, such as adding a key issue to a policy debate, using a minor scandal to undermine an opponent, or leveraging a small but influential group to sway public opinion or legislative outcomes.