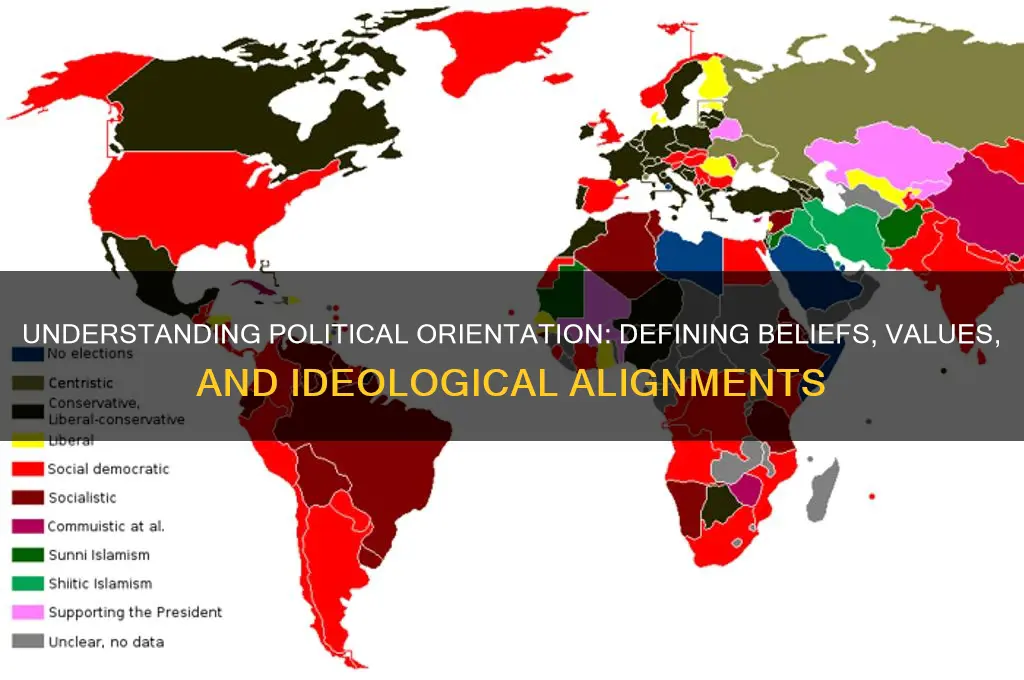

Political orientation refers to an individual's or group's stance on political issues, ideologies, and systems, often shaped by their beliefs, values, and societal context. It encompasses a spectrum of views, ranging from conservatism to liberalism, socialism, and beyond, each advocating distinct approaches to governance, economics, and social policies. Understanding political orientation is crucial as it influences voting behavior, policy preferences, and societal cohesion, reflecting deeper attitudes toward authority, equality, and individual freedoms. Factors such as upbringing, education, and cultural environment play significant roles in shaping these orientations, making them a dynamic and multifaceted aspect of human identity.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A set of beliefs, values, and attitudes about how society should be organized and governed. |

| Key Dimensions | Economic (e.g., left vs. right), social (e.g., liberal vs. conservative), and libertarian vs. authoritarian. |

| Left-Wing | Emphasizes equality, social welfare, progressive policies, and government intervention. |

| Right-Wing | Focuses on individualism, free markets, traditional values, and limited government. |

| Liberal | Supports individual freedoms, social progressivism, and minority rights. |

| Conservative | Values tradition, established institutions, and gradual change. |

| Libertarian | Prioritizes individual liberty, minimal government, and free markets. |

| Authoritarian | Favors strong central authority, order, and often restricts personal freedoms. |

| Environmental Focus | Varies from green politics (left) to skepticism about regulation (right). |

| Global vs. National | Ranges from globalist (international cooperation) to nationalist (sovereignty). |

| Role of Government | Left: Active role in welfare; Right: Limited role, emphasis on private sector. |

| Social Issues | Left: Progressive (e.g., LGBTQ+ rights); Right: Traditional (e.g., family values). |

| Economic Policies | Left: Redistribution, taxation; Right: Deregulation, lower taxes. |

| Cultural Attitudes | Left: Multiculturalism; Right: Cultural homogeneity. |

| Influencing Factors | Socioeconomic status, education, geography, and generational differences. |

| Political Parties | Examples: Democrats (U.S., center-left), Republicans (U.S., center-right), Labour (UK, left), Conservatives (UK, right). |

| Recent Trends | Rise of populism, polarization, and identity politics globally. |

Explore related products

$20.22 $25.99

$8 $8

What You'll Learn

- Ideological Foundations: Core beliefs shaping political views, such as liberalism, conservatism, socialism, or authoritarianism

- Spectrum Placement: Left, right, or center positioning based on economic and social policies

- Cultural Influences: Role of traditions, religion, and societal norms in shaping political beliefs

- Policy Priorities: Focus on issues like healthcare, education, economy, or national security

- Historical Context: How past events and movements influence current political orientations

Ideological Foundations: Core beliefs shaping political views, such as liberalism, conservatism, socialism, or authoritarianism

Political orientation is fundamentally shaped by ideological foundations—core beliefs that act as lenses through which individuals interpret societal structures, governance, and human nature. These foundations, such as liberalism, conservatism, socialism, and authoritarianism, are not mere labels but frameworks that guide policy preferences, moral judgments, and even personal identities. Understanding these ideologies requires dissecting their underlying principles, historical contexts, and real-world manifestations.

Consider liberalism, which champions individual liberty, equality under the law, and democratic governance. Rooted in the Enlightenment, liberalism prioritizes personal freedoms, free markets, and limited government intervention in private affairs. For instance, a liberal might advocate for progressive taxation to fund social services while opposing restrictions on speech or reproductive rights. However, liberalism’s emphasis on individualism can clash with collective needs, as seen in debates over healthcare or climate policy. Its strength lies in fostering innovation and personal autonomy, but critics argue it can exacerbate inequality if left unchecked.

In contrast, conservatism emphasizes tradition, stability, and hierarchical order. Conservatives often view societal norms and institutions as time-tested safeguards against chaos, advocating for strong national identity, religious values, and law and order. For example, a conservative might support lower taxes to encourage economic growth while opposing radical social reforms. Yet, conservatism’s resistance to change can hinder progress on issues like LGBTQ+ rights or racial justice. Its appeal lies in preserving cultural continuity, but it risks stifling adaptation to modern challenges.

Socialism, meanwhile, focuses on collective welfare, economic equality, and public ownership of resources. Emerging as a critique of capitalism’s inequalities, socialism seeks to redistribute wealth and empower workers. A socialist might propose nationalizing healthcare or raising corporate taxes to fund education. However, socialism’s implementation varies widely—from Nordic social democracies to authoritarian regimes—highlighting its flexibility and potential pitfalls. While it addresses systemic inequities, critics warn of inefficiency and reduced incentives in fully centralized systems.

Authoritarianism stands apart, prioritizing order, control, and the concentration of power. Unlike the other ideologies, it is less about economic or social principles and more about governance style. Authoritarian regimes suppress dissent, centralize authority, and often use nationalism or fear to maintain control. For instance, leaders might justify surveillance or censorship as necessary for stability. While authoritarianism can deliver rapid decision-making, it comes at the cost of individual freedoms and accountability. Its enduring appeal lies in its promise of security, but history shows it often leads to oppression and corruption.

In practice, these ideologies rarely exist in pure form; most individuals and systems blend elements of multiple frameworks. For example, a liberal democracy might adopt conservative fiscal policies or socialist welfare programs. Understanding these ideological foundations is crucial for navigating political discourse, as they shape not only policies but also the values that underpin them. By examining their strengths, weaknesses, and trade-offs, one can better grasp the complexities of political orientation and its impact on society.

Spotify's Political Ad Policy: What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Spectrum Placement: Left, right, or center positioning based on economic and social policies

Political orientation often simplifies complex beliefs into a left-right spectrum, but this framework is more nuanced than it appears. At its core, the spectrum places individuals based on their views of economic and social policies. The left typically advocates for greater government intervention in the economy to promote equality, while the right emphasizes free markets and individual responsibility. Socially, the left tends to support progressive reforms and collective rights, whereas the right often champions traditional values and personal freedoms. However, this binary can oversimplify diverse perspectives, as many individuals hold views that don’t neatly align with either side.

To understand your placement, consider your stance on key economic policies. Do you support higher taxes on the wealthy to fund social programs, or do you believe lower taxes stimulate economic growth? Left-leaning individuals often prioritize wealth redistribution and public services, while right-leaning individuals may favor deregulation and limited government spending. For instance, a proposal to increase corporate taxes to fund universal healthcare would align with left-wing economics, whereas opposition to such a measure, citing potential harm to businesses, reflects a right-wing perspective. Centrists might advocate for a balanced approach, such as targeted tax increases paired with fiscal responsibility.

Social policies further complicate spectrum placement, as they often intersect with cultural and moral beliefs. Left-leaning individuals typically support issues like LGBTQ+ rights, abortion access, and immigration reform, viewing these as matters of equality and justice. Right-leaning individuals may oppose such measures, emphasizing religious values, national sovereignty, or individual liberties. For example, a left-wing voter might prioritize transgender rights legislation, while a right-wing voter could argue for stricter immigration controls. Centrists often seek compromise, such as supporting legal immigration while addressing border security concerns.

Practical tips for determining your placement include examining your reactions to current events. If you consistently side with policies that expand government roles in addressing inequality, you likely lean left. Conversely, if you favor limited government and individual initiative, you may lean right. Centrism often emerges from a desire to blend both perspectives, though critics argue it can lack ideological coherence. To avoid oversimplification, consider specific issues rather than broad labels. For instance, you might support left-wing economic policies but hold right-wing views on national security, placing you in a more nuanced position on the spectrum.

Ultimately, spectrum placement is a tool, not a rigid rule. It helps categorize broad tendencies but fails to capture the complexity of individual beliefs. For example, a person might support left-wing economic policies for their community but hold socially conservative views on certain issues. Such contradictions highlight the limitations of the left-right framework. Instead of forcing yourself into a box, use the spectrum as a starting point for deeper self-reflection and dialogue. Understanding your placement can foster clearer political engagement, but it’s equally important to recognize the gray areas that define human ideology.

Are Political Opinions Plagiarized? Exploring Authenticity in Public Discourse

You may want to see also

Cultural Influences: Role of traditions, religion, and societal norms in shaping political beliefs

Traditions, religion, and societal norms act as silent architects of political orientation, embedding values and beliefs into the very fabric of individual and collective identity. Consider the enduring influence of familial traditions: a child raised in a household that celebrates national holidays with patriotic fervor is more likely to internalize nationalist sentiments. These rituals, often passed down through generations, serve as unspoken lessons in civic duty and ideological alignment. For instance, in the United States, families that commemorate Independence Day with flag-raising ceremonies and discussions of freedom often raise children who prioritize conservative values like patriotism and limited government intervention.

Religion, too, plays a pivotal role in shaping political beliefs by offering a moral and ethical framework that extends beyond spiritual practice. Take the Catholic Church’s teachings on social justice, which have historically influenced left-leaning policies in countries like Ireland and Poland. Conversely, evangelical Christianity in the U.S. often aligns with conservative political agendas, emphasizing issues like abortion and traditional marriage. A 2019 Pew Research study found that 63% of white evangelicals identified as Republican or leaned Republican, compared to 22% who identified with the Democratic Party. This data underscores how religious doctrine can directly translate into political affiliation, often without conscious deliberation.

Societal norms, the unwritten rules governing acceptable behavior, further reinforce political orientations by dictating what is considered "right" or "wrong" in a given culture. In Japan, for example, the emphasis on harmony and collective well-being has historically fostered support for centrist or conservative policies that prioritize stability over radical change. Similarly, in Scandinavian countries, the norm of egalitarianism has driven widespread acceptance of progressive taxation and robust welfare systems. These norms are not static; they evolve, but their influence on political beliefs remains profound. A practical tip for understanding this dynamic is to examine how media and education systems perpetuate or challenge these norms, as they often act as gatekeepers of cultural values.

To illustrate the interplay of these cultural forces, consider India, where Hinduism’s caste system has historically shaped political discourse. Despite legal abolition, caste-based inequalities persist, influencing voting patterns and policy preferences. Lower-caste communities often support parties advocating for affirmative action, while upper-caste groups may favor those promoting meritocracy. This example highlights how deeply ingrained cultural structures can create enduring political divisions. For those seeking to navigate or influence political beliefs, recognizing these cultural undercurrents is essential. A cautionary note: attempting to reshape political orientation without acknowledging these influences risks superficial solutions that fail to address root causes.

In conclusion, traditions, religion, and societal norms are not mere background elements but active agents in the formation of political orientation. Their power lies in their subtlety—they shape beliefs through repetition, ritual, and shared understanding. To effectively engage with or alter political ideologies, one must first map these cultural influences. Start by identifying the traditions, religious teachings, and norms that dominate a given society. Analyze how they intersect with political discourse, and consider how they might be leveraged or challenged. This approach, while complex, offers a more nuanced and effective pathway to understanding and influencing political beliefs.

Are Political Flags Legally Classified as Signs? Exploring the Debate

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Policy Priorities: Focus on issues like healthcare, education, economy, or national security

Political orientation often hinges on policy priorities, which reveal how individuals or groups believe society’s challenges should be addressed. Healthcare, education, the economy, and national security are perennial issues, but their relative importance varies sharply across the ideological spectrum. For instance, a progressive might argue that universal healthcare is a human right, while a conservative may emphasize market-driven solutions to reduce costs. These stances aren’t just abstract—they shape legislation, budgets, and public discourse. Understanding these priorities requires examining not just the *what* but the *why* behind them, as they reflect deeper values about the role of government and individual responsibility.

Consider healthcare: a policy priority for nearly every political orientation, yet approached with stark differences. A liberal-leaning administration might push for expanded public options, citing studies showing that countries with universal healthcare have lower mortality rates and higher life expectancies. In contrast, a libertarian perspective could advocate for deregulation, arguing that competition drives innovation and affordability. Practical implementation matters too—a single-payer system requires significant tax increases, while a free-market approach risks leaving vulnerable populations uninsured. The takeaway? Policy priorities in healthcare aren’t just about access; they’re about balancing equity and efficiency.

Education policy similarly reveals ideological fault lines. A social democrat might champion increased public funding for schools, free college tuition, and teacher salary hikes, viewing education as a public good that reduces inequality. Conversely, a conservative could prioritize school choice and voucher programs, believing parental control fosters accountability. These approaches aren’t mutually exclusive—for example, charter schools can coexist with traditional public systems—but their emphasis differs. For parents and policymakers, the challenge lies in aligning these priorities with measurable outcomes, such as graduation rates or workforce readiness, without losing sight of long-term societal goals.

Economic policy priorities often dominate political debates, yet their specifics can be misleadingly simple. A left-leaning government might focus on progressive taxation and wealth redistribution to address income inequality, while a right-leaning one could prioritize deregulation and tax cuts to stimulate growth. However, the devil is in the details: a 2% corporate tax cut might boost short-term investment but widen the deficit, whereas a $15 minimum wage could lift workers out of poverty but risk job losses in small businesses. The key is to evaluate these policies not in isolation but as part of a broader economic ecosystem, considering trade-offs and unintended consequences.

National security, though often framed as nonpartisan, is deeply influenced by political orientation. A hawkish administration might increase defense spending and pursue aggressive foreign interventions, viewing military strength as a deterrent. In contrast, a dovish approach could prioritize diplomacy, foreign aid, and multilateral agreements, emphasizing conflict prevention over confrontation. These priorities aren’t just about ideology—they’re shaped by historical context, such as the Cold War legacy or post-9/11 security concerns. For citizens, understanding these perspectives requires critically assessing whether a policy enhances security or perpetuates instability, and at what cost to civil liberties or global alliances.

In sum, policy priorities are the backbone of political orientation, reflecting not just what issues matter but how they should be addressed. Whether in healthcare, education, the economy, or national security, these priorities are shaped by competing values, practical constraints, and ideological goals. By dissecting these differences, individuals can better navigate political discourse, advocate for their beliefs, and hold leaders accountable for the choices they make. After all, policy isn’t just about ideas—it’s about the tangible impact on people’s lives.

Vinnie Politan's Family Life: Does He Have Children?

You may want to see also

Historical Context: How past events and movements influence current political orientations

The French Revolution's echoes still resonate in modern political ideologies. Its core tenets—liberty, equality, fraternity—became rallying cries for democratic movements worldwide. This revolution dismantled absolute monarchy, challenging the divine right of kings and asserting popular sovereignty. Today, its legacy is evident in the widespread adoption of democratic principles, from universal suffrage to constitutional governance. However, the revolution's violent excesses also serve as a cautionary tale, reminding us of the dangers of unchecked radicalism. This historical event underscores how past struggles for power and justice shape contemporary political orientations, influencing everything from policy debates to civic engagement.

Consider the Civil Rights Movement in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s. This struggle for racial equality not only transformed American society but also redefined global perceptions of justice and human rights. Figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X embodied contrasting approaches—nonviolent resistance versus militant activism—both of which continue to inspire political movements today. The movement's successes, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, laid the groundwork for subsequent campaigns for LGBTQ+ rights, gender equality, and immigrant rights. Its failures, particularly in addressing systemic economic inequality, highlight the ongoing challenges of translating legislative victories into tangible societal change.

The Cold War, a decades-long ideological standoff between capitalism and communism, polarized global politics and left an indelible mark on contemporary orientations. It fostered a binary worldview, where nations aligned with either the United States or the Soviet Union, shaping foreign policies and domestic agendas. Even after its end, its legacy persists in the form of geopolitical tensions, such as those between the U.S. and China. The Cold War also spurred significant advancements in technology, space exploration, and military strategy, but at the cost of heightened global anxiety and the proliferation of nuclear weapons. Its influence is still felt in debates over national security, surveillance, and the role of government in individual lives.

To understand how historical events shape political orientations, examine the decolonization movements of the 20th century. As European powers relinquished control over their colonies, newly independent nations grappled with questions of identity, governance, and economic development. These struggles often led to the adoption of diverse political systems, from socialist regimes in countries like Cuba to democratic experiments in India. The aftermath of decolonization also fueled nationalist and separatist movements, as seen in the breakup of Yugoslavia and ongoing conflicts in the Middle East. Practical takeaways include recognizing the importance of context in political decision-making and the need for inclusive policies that address historical grievances.

Finally, the rise of neoliberalism in the late 20th century, championed by leaders like Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, reshaped global economic and political landscapes. This ideology emphasized free markets, deregulation, and privatization, leading to unprecedented economic growth but also widening inequality. Its influence is evident in the dominance of corporate interests in politics, the erosion of social safety nets, and the global financial crisis of 2008. Critics argue that neoliberalism prioritizes profit over people, while proponents credit it with lifting millions out of poverty. Understanding this historical shift is crucial for navigating current debates on taxation, healthcare, and labor rights, offering a lens through which to analyze the trade-offs between individual freedom and collective welfare.

Is Pam Bondy Exiting Politics? Exploring Her Future Plans

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political orientation refers to an individual's or group's stance on political issues, ideologies, and principles, often categorized as left-wing, right-wing, or centrist.

Political orientation is determined by one's beliefs about the role of government, economic policies, social issues, and individual freedoms, often shaped by personal values, culture, and experiences.

The main types are left-wing (emphasizing equality, social welfare, and progressive change), right-wing (focusing on tradition, free markets, and limited government), and centrist (seeking a balance between the two).

Yes, political orientation can change due to shifts in personal beliefs, societal changes, exposure to new ideas, or experiences that alter one's perspective on political issues.

Understanding political orientation helps explain voting behavior, policy preferences, and societal divisions, fostering better dialogue and cooperation across differing viewpoints.