Political opinion polls are systematic surveys designed to gauge public sentiment on political issues, candidates, or policies by collecting and analyzing data from a representative sample of the population. These polls serve as essential tools for understanding voter preferences, predicting election outcomes, and informing political strategies. Conducted through various methods such as telephone interviews, online questionnaires, or in-person surveys, they provide insights into public opinion trends, helping politicians, media outlets, and researchers make informed decisions. While widely used, their accuracy depends on factors like sample size, question wording, and timing, and they often spark debates about their influence on voter behavior and the democratic process.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Surveys to measure public opinion on political candidates, parties, or issues. |

| Purpose | Predict election outcomes, gauge public sentiment, guide campaigns. |

| Methods | Telephone interviews, online surveys, in-person polling, mail surveys. |

| Sample Size | Typically ranges from 1,000 to 3,000 respondents for national polls. |

| Margin of Error | Usually ±3% to ±5% for reliable polls. |

| Frequency | Conducted regularly, especially during election seasons. |

| Key Metrics | Candidate approval ratings, party support, issue priorities. |

| Challenges | Response bias, non-response bias, changing voter preferences. |

| Regulation | Varies by country; some nations have laws governing poll transparency. |

| Impact | Influences media narratives, campaign strategies, and voter behavior. |

| Examples | Gallup, Pew Research Center, Ipsos, Quinnipiac Polls. |

| Latest Trends | Increased use of AI and big data analytics for predictive modeling. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Poll Methodology: Techniques and tools used to collect, analyze, and interpret public political opinions

- Sampling Techniques: Methods to select representative groups for accurate and reliable polling results

- Bias in Polls: Factors like question wording, timing, and demographics that skew poll outcomes

- Poll Accuracy: Historical reliability of polls in predicting election results and public sentiment

- Poll Influence: How political opinion polls shape voter behavior, media narratives, and campaign strategies

Poll Methodology: Techniques and tools used to collect, analyze, and interpret public political opinions

Political opinion polls are snapshots of public sentiment, but their accuracy hinges on rigorous methodology. At the heart of this process is sampling, the art of selecting a subset of the population that accurately reflects the whole. Pollsters employ probability sampling techniques like random digit dialing or stratified sampling to ensure every demographic group—age, gender, race, region—is proportionally represented. For instance, a national poll might aim for a sample size of 1,000 respondents, with margins of error typically ranging from ±3% to ±5%. Non-probability methods, such as online panels or voluntary response samples, are cheaper and faster but risk bias, as seen in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, where over-reliance on convenience samples skewed predictions.

Once the sample is set, questionnaire design becomes critical. Questions must be clear, unbiased, and structured to avoid leading responses. For example, asking, "Do you support increased funding for education?" is less biased than, "Should we prioritize education over defense spending?" Pollsters often use Likert scales (e.g., "Strongly Agree" to "Strongly Disagree") to capture nuanced opinions. Pre-testing questions with focus groups ensures clarity and relevance. A poorly worded question can distort results, as demonstrated in a 1992 poll where ambiguous phrasing led to a 10% swing in responses on a healthcare policy.

Data collection tools have evolved significantly, with telephone surveys, online polls, and in-person interviews each offering unique advantages. Telephone surveys, though declining in response rates (often below 10%), remain gold standard for randomness. Online polls, while cost-effective, suffer from self-selection bias, as participants tend to be younger and more tech-savvy. In-person interviews, though expensive, yield higher response rates and are ideal for complex questions. Hybrid approaches, combining multiple methods, are increasingly popular to mitigate individual tool limitations.

Analyzing and interpreting data requires statistical rigor. Weighting adjusts raw data to match known population demographics, correcting for under- or over-representation. For example, if a sample has 60% women but the population has 51%, responses from men are weighted more heavily. Cross-tabulation breaks down results by subgroups (e.g., age or party affiliation) to reveal patterns. Regression analysis identifies correlations between variables, such as income level and voting preference. However, correlation does not imply causation—a common pitfall in political polling.

Finally, transparency and ethical considerations are paramount. Pollsters must disclose methodology, including sample size, response rate, and margin of error, to allow for informed interpretation. Ethical concerns arise with push polling, where questions are designed to sway opinions rather than measure them. For instance, a 2008 push poll asked, "If you knew Candidate X had been accused of corruption, would you still vote for them?" Such tactics undermine public trust. Adhering to industry standards, like those set by the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR), ensures polls serve as tools for democracy, not manipulation.

Understanding Political Nihilism: Origins, Beliefs, and Societal Implications Explained

You may want to see also

Sampling Techniques: Methods to select representative groups for accurate and reliable polling results

The accuracy of political opinion polls hinges on the representativeness of the sample. A biased sample skews results, rendering the poll useless. To ensure accuracy, pollsters employ various sampling techniques, each with its strengths and weaknesses.

Understanding these methods is crucial for interpreting poll results and identifying potential sources of error.

Probability Sampling: The Gold Standard

One of the most reliable methods is probability sampling, where every member of the population has a known, non-zero chance of being selected. This ensures the sample reflects the diversity of the population. Common probability sampling techniques include:

- Simple Random Sampling: Imagine selecting names from a hat. Each individual has an equal chance of being chosen. This method is straightforward but can be time-consuming for large populations.

- Stratified Sampling: The population is divided into subgroups (strata) based on relevant characteristics like age, gender, or region. Samples are then randomly drawn from each stratum in proportion to their representation in the population. This ensures adequate representation of key demographic groups. For instance, a poll on healthcare policy might stratify by age groups (18-34, 35-54, 55+) to capture differing perspectives.

- Cluster Sampling: The population is divided into clusters (e.g., neighborhoods, cities), and a random selection of clusters is chosen. All individuals within the selected clusters are then surveyed. This method is cost-effective for large, geographically dispersed populations but may introduce cluster-level bias.

Non-Probability Sampling: Convenience and Compromise

While probability sampling is ideal, it's not always feasible. Non-probability sampling methods, where the selection process is not random, are often used due to cost or time constraints. These methods are more susceptible to bias but can still provide valuable insights if used judiciously.

- Convenience Sampling: Surveying readily available individuals, like passersby in a public square, is convenient but highly biased towards those who happen to be in that location at that time.

- Quota Sampling: Pollsters set quotas for specific demographic groups and continue sampling until the quotas are met. This ensures representation of key groups but relies on the interviewer's judgment, potentially introducing bias.

The Trade-Off: Precision vs. Practicality

The choice of sampling technique involves a trade-off between precision and practicality. Probability sampling offers greater accuracy but can be resource-intensive. Non-probability sampling is more convenient but carries a higher risk of bias. Pollsters must carefully consider the research objectives, budget, and time constraints when selecting the most appropriate method.

Evaluating FiveThirtyEight's Political Predictions: Accuracy and Reliability Explored

You may want to see also

Bias in Polls: Factors like question wording, timing, and demographics that skew poll outcomes

Political opinion polls are snapshots of public sentiment, but they’re far from infallible. One of the most insidious culprits behind skewed results is question wording. Consider a poll asking, "Do you support increased government spending on healthcare?" versus "Do you think taxpayers should bear the burden of higher healthcare costs?" The first frames the issue positively, potentially inflating support, while the second introduces a negative connotation, likely suppressing it. This phenomenon, known as framing bias, demonstrates how subtle linguistic choices can manipulate responses. Pollsters must craft neutral, unambiguous questions to avoid leading participants toward predetermined answers. For instance, using specific, measurable terms like "increased funding" instead of vague phrases like "more resources" can reduce bias.

Timing is another critical factor that can distort poll outcomes. A survey conducted during a major political scandal will yield vastly different results than one taken during a period of relative calm. For example, a poll on presidential approval ratings taken immediately after a successful foreign policy initiative will likely show higher approval than one conducted during an economic downturn. This recency bias highlights how current events disproportionately influence public opinion. To mitigate this, pollsters should either time surveys strategically or acknowledge the temporal context in their analysis. A practical tip: cross-reference results with historical data to identify anomalies caused by timing.

Demographics play an equally pivotal role in shaping poll results. A survey that over-represents urban, college-educated respondents will not accurately reflect the views of a broader, more diverse population. This sampling bias is particularly problematic in political polls, where opinions often vary sharply by age, race, income, and geographic location. For instance, a poll on climate change policy might show overwhelming support if it disproportionately includes younger, urban respondents, while rural or older participants may hold different views. To ensure accuracy, pollsters must employ stratified sampling, weighting responses to match the actual demographic distribution of the target population. Tools like census data can guide this process, ensuring representation across key groups.

Finally, the mode of polling—whether conducted via phone, online, or in-person—can introduce further biases. Phone polls, for instance, often under-represent younger voters who rely on mobile phones and may not answer unknown numbers. Online polls, while cost-effective, can exclude those without internet access, typically older or lower-income individuals. This mode bias underscores the importance of selecting methods that align with the target audience. A hybrid approach, combining multiple modes, can improve coverage. For example, pairing phone surveys with online panels can capture a wider range of respondents, though each method’s limitations must be acknowledged in the analysis.

In conclusion, while political opinion polls are valuable tools for gauging public sentiment, their reliability hinges on addressing biases in question wording, timing, demographics, and polling methods. By understanding these factors and implementing strategies to counteract them, pollsters can produce more accurate and meaningful results. For consumers of poll data, a critical eye toward these biases is essential to interpreting findings correctly. After all, the truth in the numbers lies not just in what’s reported, but in how it’s gathered.

Understanding Political Liberalism: Core Principles and Modern Applications

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Poll Accuracy: Historical reliability of polls in predicting election results and public sentiment

Political opinion polls have long been a cornerstone of democratic societies, offering snapshots of public sentiment and predictions about election outcomes. However, their accuracy has been a subject of intense scrutiny, particularly after high-profile misses like the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Historically, polls have been reliable within a margin of error, typically ±3%, but this reliability hinges on methodology, sample size, and timing. For instance, the 2012 U.S. election saw polls accurately predict Barack Obama’s victory, with an average error of just 1.5%. Yet, such successes are not universal, and understanding the factors behind both hits and misses is crucial for interpreting poll results.

To assess poll accuracy, consider the methodology employed. Random sampling, weighted demographics, and question phrasing are critical components. For example, landline-only polls in the 1990s often overrepresented older voters, skewing results. Today, online panels and mobile polling introduce new biases, such as underrepresenting rural or low-income populations. A 2020 Pew Research study found that polls using landline and cellphone samples were 1.5% more accurate than online-only surveys. Practical tip: Look for polls that disclose their sampling method and margin of error to gauge reliability.

One instructive example is the 1948 U.S. presidential election, where polls predicted Thomas Dewey’s victory over Harry Truman. The error stemmed from early polling cutoff dates and reliance on small, non-random samples. This historical blunder highlights the importance of timing and sample diversity. Modern pollsters now conduct surveys closer to election day and use larger, more representative samples. Caution: Polls taken weeks before an election may not capture late-breaking shifts in voter sentiment, as seen in the 2019 U.K. general election, where Labour’s support dropped sharply in the final days.

Comparatively, polls in stable democracies like Germany and Canada have consistently higher accuracy rates, often within ±2%. This is partly due to their proportional representation systems, which reduce volatility in voter behavior. In contrast, winner-takes-all systems like the U.S. Electoral College amplify small polling errors, turning a 1% miscalculation into a missed prediction. Takeaway: Context matters. Polls in multiparty systems or countries with mandatory voting tend to be more reliable due to predictable voter turnout patterns.

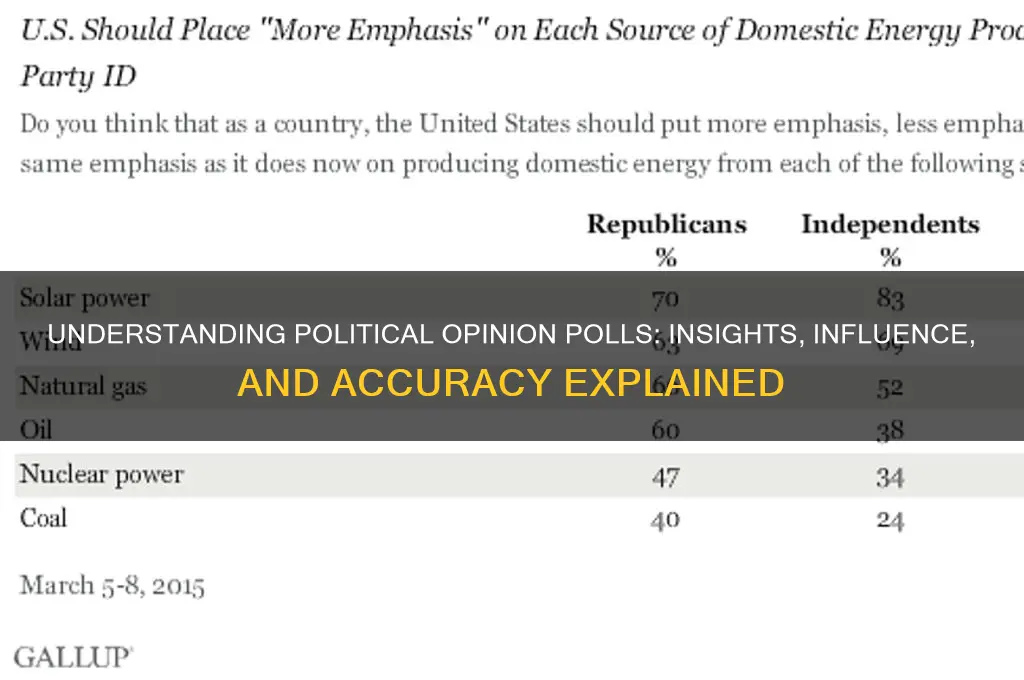

Finally, public sentiment polls, which gauge opinions on issues rather than candidates, face unique challenges. While they often predict broad trends—such as rising climate change concern—they struggle with nuanced topics. For instance, a 2018 Gallup poll on gun control showed 67% support for stricter laws, yet legislative action remained stagnant. This disconnect underscores the gap between stated opinions and actionable behavior. Practical tip: Treat sentiment polls as indicators of mood, not predictors of policy outcomes. Their value lies in tracking shifts over time, not in forecasting immediate changes.

Are Political Differences Protected? Exploring Free Speech and Legal Boundaries

You may want to see also

Poll Influence: How political opinion polls shape voter behavior, media narratives, and campaign strategies

Political opinion polls are more than just numbers; they are powerful tools that can sway elections, dictate media coverage, and redefine campaign tactics. Consider this: during the 2016 U.S. presidential race, a single poll showing Donald Trump gaining ground in key swing states prompted a surge in media attention, donor funding, and voter mobilization. This example underscores how polls don’t merely reflect public sentiment—they actively shape it. By signaling momentum or stagnation, polls can create a self-fulfilling prophecy, influencing undecided voters, energizing bases, and even altering the trajectory of a campaign.

To understand how polls mold voter behavior, imagine a scenario where two candidates are neck-and-neck. A poll released a week before the election shows one candidate pulling ahead by 5%. For undecided voters, this can trigger a psychological phenomenon known as the "bandwagon effect," where individuals gravitate toward the perceived winner. Conversely, supporters of the trailing candidate may feel a sense of urgency, increasing turnout efforts. Practical tip: Campaigns often use such polls to craft targeted messages, like emphasizing electability or rallying cries to close the gap. Voters, meanwhile, should critically evaluate poll methodology (sample size, margin of error) to avoid being unduly swayed.

Media narratives are equally captive to poll results. News outlets thrive on conflict and drama, and polls provide the raw material for sensational headlines. A poll showing a dramatic shift in public opinion can dominate news cycles, framing the narrative for days. For instance, during Brexit, polls predicting a close race fueled media speculation about economic fallout and political upheaval, amplifying both pro-Leave and pro-Remain arguments. Caution: Media often oversimplify poll findings, focusing on topline numbers without context. Readers should seek out detailed breakdowns, such as demographic splits or regional variations, to gain a fuller picture.

Campaign strategies are perhaps the most poll-dependent aspect of modern politics. Campaigns invest heavily in internal polling to test messages, identify weaknesses, and allocate resources. For example, a poll revealing a candidate’s healthcare plan resonates strongly with suburban women aged 30–50 might prompt the campaign to run targeted ads in those areas. Conversely, a poll showing a candidate underperforming among young voters could lead to increased social media outreach and grassroots events on college campuses. Takeaway: Polls are not just diagnostic tools—they are strategic blueprints, guiding everything from ad buys to debate prep.

In conclusion, political opinion polls are not passive observers of the electoral process; they are active participants that can amplify trends, shift narratives, and dictate actions. Voters, media, and campaigns alike must navigate this landscape with awareness and skepticism. For voters, understanding poll mechanics can prevent herd mentality. For journalists, contextualizing poll data ensures responsible reporting. For campaigns, leveraging polls strategically can mean the difference between victory and defeat. In a world where information is power, polls are the currency—and their influence is undeniable.

Do Political Postcards Sway Voters? Analyzing Their Campaign Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political opinion poll is a survey conducted to gather public opinion on political issues, candidates, or policies. It aims to measure the sentiments and preferences of a specific population, often used to predict election outcomes or gauge public support for certain topics.

Political opinion polls are conducted through various methods, including phone calls, online surveys, in-person interviews, or mail questionnaires. Pollsters use random sampling techniques to ensure the results are representative of the target population.

Political opinion polls are important because they provide insights into public sentiment, help politicians and parties tailor their campaigns, and assist media outlets in reporting on public attitudes. They also serve as a tool for predicting election results and tracking trends over time.

Political opinion polls are not always accurate due to factors like sampling errors, response bias, or changes in public opinion between the poll and the event (e.g., an election). However, when conducted rigorously and transparently, they can provide reliable estimates of public opinion.