The question of whether political opinions can be considered plagiarism is a nuanced and thought-provoking one, as it intersects the realms of intellectual property, originality, and public discourse. While plagiarism traditionally refers to the unauthorized use of someone else’s ideas or words as one’s own, political opinions often emerge from shared ideologies, historical contexts, or collective movements, making it difficult to attribute them to a single individual. Politicians, pundits, and citizens frequently echo similar stances on issues like healthcare, climate change, or economic policies, raising the question: does repeating a widely held belief constitute plagiarism, or is it simply participation in a broader conversation? This debate challenges us to reconsider the boundaries of originality in political thought and the role of collective ideas in shaping individual opinions.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Political opinions are not considered plagiarism as they are personal beliefs and interpretations, not factual data or original works. |

| Originality | Political opinions are inherently subjective and unique to individuals, making them original by nature. |

| Attribution | No attribution is required for political opinions, as they are not borrowed or copied from others. |

| Ethical Considerations | Expressing political opinions is protected by freedom of speech, but ethical concerns arise when opinions are presented as facts without evidence. |

| Academic Context | In academic writing, political opinions must be supported by evidence and properly cited if referencing others' ideas. |

| Legal Implications | Political opinions are generally protected under free speech laws, but defamation or hate speech may have legal consequences. |

| Cultural Influence | Political opinions can be influenced by cultural, social, and historical contexts, but this does not constitute plagiarism. |

| Public Discourse | Sharing political opinions in public discourse is common and encouraged, as long as it respects differing viewpoints. |

| Educational Impact | Teaching political opinions in education aims to foster critical thinking and debate, not to replicate others' views. |

| Media Representation | Media outlets often present political opinions, but they must distinguish between opinion pieces and factual reporting. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition of Plagiarism in Politics: Exploring if political views can be considered plagiarized content

- Originality in Political Speeches: Analyzing whether politicians must always present entirely unique ideas

- Shared Ideologies vs. Plagiarism: Differentiating between common beliefs and copied political opinions

- Legal Implications of Idea Theft: Examining if plagiarized political opinions have legal consequences

- Ethics of Borrowing Political Views: Discussing the moral boundaries of adopting others’ political stances

Definition of Plagiarism in Politics: Exploring if political views can be considered plagiarized content

Plagiarism, traditionally defined as the unauthorized use of someone else’s ideas or words, is a clear violation in academic and creative fields. But what happens when we apply this concept to the realm of politics? Political opinions, often shaped by collective ideologies, historical contexts, and shared values, blur the lines of originality. For instance, a politician advocating for universal healthcare might echo the same arguments as their predecessors or contemporaries. Does this constitute plagiarism, or is it merely the repetition of a widely accepted stance? The challenge lies in distinguishing between the appropriation of unique intellectual property and the expression of common beliefs within a political movement.

To explore this, consider the analytical framework of intellectual property rights. In academia, plagiarism is actionable because it involves the theft of original work, often with tangible consequences like grades or publications. Political opinions, however, are rarely protected by copyright or patents. They exist in a public domain, where ideas are freely exchanged and debated. For example, the concept of "tax cuts for the middle class" has been a recurring theme across multiple political parties and eras. While one politician might phrase it differently from another, the core idea remains unchanged. Here, the lack of legal or ethical recourse suggests that political views are not subject to the same plagiarism standards as academic or creative works.

From a persuasive standpoint, labeling political opinions as plagiarized could stifle public discourse. Politics thrives on the exchange of ideas, often building on the successes and failures of past policies. If politicians were required to ensure their views were entirely original, it could lead to a paralysis of thought, where fear of accusation overshadows the need for effective governance. Take the Green New Deal, a policy framework inspired by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. While it draws heavily from historical precedent, it adapts those ideas to address contemporary challenges like climate change. Penalizing such adaptations as plagiarism would undermine the iterative nature of political progress.

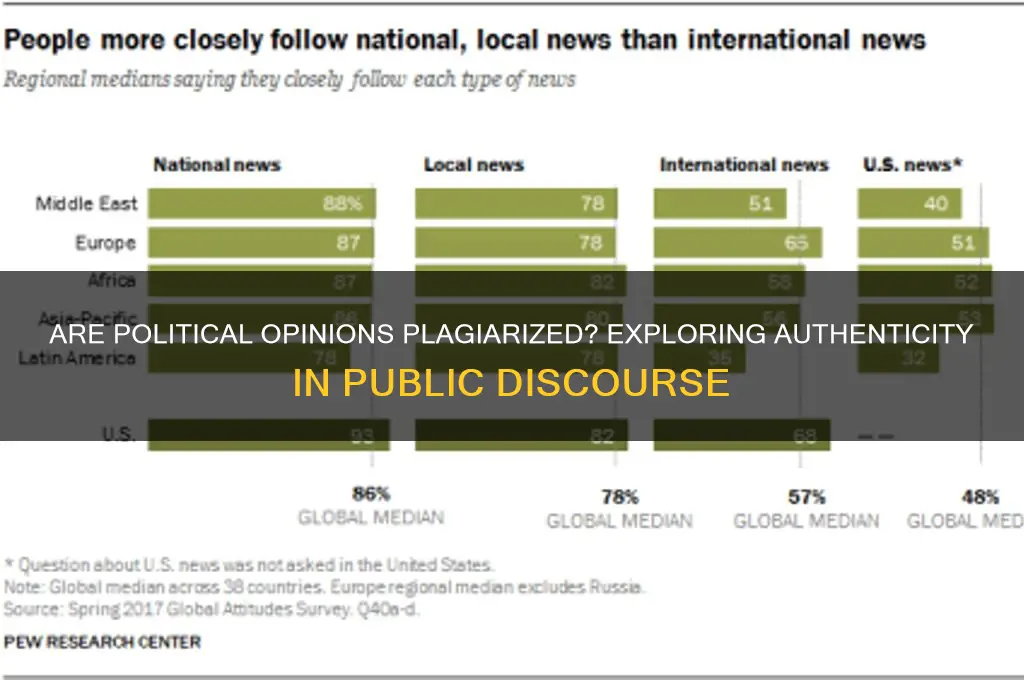

Comparatively, the media’s role in shaping political narratives complicates this issue further. Journalists and commentators often frame political debates, influencing how ideas are presented and perceived. When a politician adopts a stance popularized by the media, is it plagiarism or simply alignment with public sentiment? For instance, the phrase "build back better" gained traction during the COVID-19 pandemic, used by leaders across the globe. While its origins can be traced to specific sources, its widespread adoption reflects a shared global response rather than intellectual theft. This highlights the difficulty in applying a rigid plagiarism framework to a fluid, dynamic field like politics.

In conclusion, while plagiarism in politics lacks a clear definition, the nature of political discourse suggests that opinions are unlikely to be considered plagiarized. Political ideas are often communal, shaped by collective experiences and shared goals. Attempting to enforce originality in this context could hinder collaboration and innovation. Instead, the focus should remain on the substance of policies and their impact, rather than the novelty of their presentation. As long as politicians attribute specific quotes or data, the repetition of ideas should be seen as a natural part of the political process, not a violation of intellectual integrity.

Capitalizing Political Organizations: Rules, Exceptions, and Common Mistakes Explained

You may want to see also

Originality in Political Speeches: Analyzing whether politicians must always present entirely unique ideas

Political speeches often echo familiar themes: equality, justice, economic growth. Yet, the question lingers—must these ideas be entirely original to be effective? Consider that political discourse thrives on shared values and historical precedents. For instance, references to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" in American speeches trace back to the Declaration of Independence. Such phrases are not plagiarized but repurposed to resonate with collective memory. Originality in this context may lie not in inventing new ideals but in framing them uniquely to address contemporary challenges. A politician’s ability to connect timeless principles with current issues often determines their impact, suggesting that complete novelty is less critical than relevance and authenticity.

To assess whether politicians must present entirely unique ideas, examine the role of policy proposals. Many solutions to recurring issues—tax reform, healthcare, education—draw from established frameworks or international models. For example, a politician advocating for universal healthcare might reference successful systems in Canada or the UK. While the core idea is not original, the adaptation to local contexts requires creativity. Here, originality manifests in tailoring solutions to specific cultural, economic, and political landscapes. Voters seek actionable plans, not abstract innovation, making the execution of ideas more crucial than their origin.

A persuasive argument for embracing non-original ideas lies in the collaborative nature of governance. Political ideologies—liberalism, conservatism, socialism—are shared intellectual frameworks developed over centuries. Politicians operate within these paradigms, contributing to an ongoing dialogue rather than starting anew. For instance, a speech advocating for environmental regulation might echo the Green New Deal, a concept shaped by collective input. Rejecting such ideas as unoriginal would stifle progress. Instead, politicians should focus on advancing these concepts with fresh perspectives, ensuring they remain dynamic and responsive to societal needs.

However, caution is warranted. Over-reliance on recycled ideas can lead to stagnation or accusations of intellectual laziness. Voters may perceive unattributed or overly derivative speeches as insincere or uninspired. To avoid this, politicians should balance tradition with innovation. For example, while referencing historical figures like Martin Luther King Jr. for inspiration, they should articulate how their vision differs or builds upon past efforts. This approach demonstrates respect for precedent while asserting individuality, fostering trust and engagement.

In practice, politicians can cultivate originality by focusing on delivery and context rather than content alone. A speech may address a well-worn topic but gain uniqueness through personal anecdotes, local data, or innovative metaphors. For instance, framing climate change as a "marathon, not a sprint" adds a fresh layer to a familiar issue. Additionally, engaging with opposing viewpoints and proposing hybrid solutions can showcase intellectual rigor. Ultimately, the goal is not to reinvent the wheel but to ensure it rolls smoothly on the road ahead. Originality in political speeches is thus about authenticity, adaptability, and relevance—not novelty for its own sake.

Madagascar's Political Stability: Current Challenges and Future Prospects

You may want to see also

Shared Ideologies vs. Plagiarism: Differentiating between common beliefs and copied political opinions

Political opinions, by their nature, often stem from shared ideologies—frameworks of belief that resonate across individuals, communities, or entire societies. These ideologies, whether rooted in liberalism, conservatism, socialism, or other schools of thought, provide a common language for expressing views on governance, economics, and social issues. When two people articulate similar stances on, say, healthcare reform or climate policy, it’s rarely a coincidence; they’re likely drawing from the same ideological wellspring. However, the line between sharing an ideology and plagiarizing political opinions can blur, especially when specific phrasing, arguments, or even policy proposals mirror those of a prominent figure or source. The challenge lies in distinguishing between the organic expression of a shared belief and the unoriginal repetition of someone else’s words or ideas.

Consider the following scenario: a student writes an essay advocating for universal basic income, echoing the exact arguments and examples used by a well-known economist in a viral TED Talk. While the student may genuinely believe in the idea, their failure to cite the source or add unique analysis raises questions about intellectual honesty. Here, the issue isn’t the shared belief in universal basic income—it’s the appropriation of someone else’s intellectual labor. To avoid this pitfall, individuals must engage critically with their ideological framework, adding personal insights, local context, or novel evidence to their arguments. For instance, a student could analyze how universal basic income might impact their region’s economy, differentiating their work from a mere rehash of existing content.

Instructively, the key to navigating this terrain lies in understanding the difference between *content* and *expression*. Shared ideologies provide the content—the core principles and values—but the expression of those ideas should be uniquely one’s own. A persuasive approach might involve reframing common arguments to reflect personal experiences or cultural perspectives. For example, a conservative arguing against government overreach could draw parallels to historical events in their community, rather than parroting talking points from a national pundit. This not only avoids plagiarism but also enriches the discourse by grounding abstract ideologies in tangible, relatable contexts.

Comparatively, consider the legal and academic worlds, where plagiarism is clearly defined and harshly penalized. In politics, however, the stakes are different. While copying a speech word-for-word (as occurred in a 2016 U.S. political scandal) is undeniable plagiarism, borrowing broadly accepted arguments is often seen as acceptable—even expected. The takeaway is that political discourse thrives on the exchange of ideas, but integrity demands that individuals contribute something original to the conversation. Whether through fresh analysis, local data, or a unique narrative, the goal should be to advance the ideology, not merely replicate it.

Practically, here’s a three-step guide to ensure your political opinions remain authentic:

- Identify your ideological roots: Understand the core principles driving your beliefs.

- Engage with diverse sources: Avoid relying on a single influencer or platform; broaden your research to develop a well-rounded perspective.

- Add your voice: Incorporate personal anecdotes, local data, or critical questions to make your arguments distinct.

By following these steps, you can honor shared ideologies while ensuring your political opinions are unmistakably your own.

Mastering Southern Belle Charm: Politeness Tips for Graceful Living

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Legal Implications of Idea Theft: Examining if plagiarized political opinions have legal consequences

Plagiarism, traditionally associated with academic or creative works, raises complex questions when applied to political opinions. While political discourse thrives on the exchange of ideas, the line between inspiration and theft blurs when identical arguments or phrasing appear without attribution. This phenomenon, often dismissed as rhetorical mimicry, warrants scrutiny from a legal standpoint. Can the unattributed adoption of political opinions constitute idea theft, and if so, what legal consequences might follow?

Distinguishing Ideas from Expression: A Legal Tightrope

The legal system generally protects the expression of ideas, not the ideas themselves. This distinction, rooted in copyright law, presents a challenge when addressing plagiarized political opinions. A politician echoing another's call for universal healthcare, for instance, wouldn't necessarily face legal repercussions unless they directly copied specific phrasing or unique policy details. The challenge lies in proving that the "stolen" idea is sufficiently original and concrete to warrant protection.

Broad, abstract concepts like "economic equality" or "national security" are considered part of the public domain, free for all to use and debate.

Defamation and Misrepresentation: Potential Pitfalls

While copyright infringement might be difficult to prove in cases of political opinion plagiarism, other legal avenues exist. If the plagiarized opinion is presented as the speaker's own, it could potentially lead to defamation claims if the original author's reputation is damaged. Imagine a scenario where a politician plagiarizes a controversial opinion, leading to public backlash against the original author. In such cases, the author could argue that the plagiarism misrepresented their views and caused harm to their reputation.

Additionally, misrepresentation claims could arise if the plagiarized opinion is used to deceive voters or gain unfair advantage in an election.

Ethical Considerations and the Public Trust

Beyond legal ramifications, the plagiarism of political opinions erodes public trust and undermines the integrity of democratic discourse. Voters deserve to know the genuine beliefs and ideas of their representatives. When politicians present borrowed opinions as their own, they engage in a form of intellectual dishonesty that undermines the very foundation of informed decision-making. This ethical breach, while not always legally actionable, carries significant consequences for the credibility and legitimacy of political actors.

Navigating the Gray Area: Transparency and Attribution

Given the complexities surrounding the legal implications of plagiarized political opinions, transparency and attribution emerge as crucial safeguards. Politicians and public figures should strive to acknowledge the sources of their ideas, even when drawing upon widely held beliefs. This not only demonstrates intellectual honesty but also fosters a culture of open dialogue and respectful debate. Ultimately, while the legal landscape may be murky, the ethical imperative for transparency in political discourse remains clear.

Emma Watson's Political Involvement: Activism or Future Career Move?

You may want to see also

Ethics of Borrowing Political Views: Discussing the moral boundaries of adopting others’ political stances

Political opinions, unlike academic works or creative expressions, are not protected by intellectual property laws. Yet, the act of borrowing or adopting someone else’s political stance raises ethical questions that extend beyond legality. When individuals align themselves with the views of public figures, thinkers, or movements, they often do so without acknowledging the source. This practice, while common, blurs the line between genuine conviction and intellectual laziness. For instance, repeating a politician’s talking points verbatim during a debate might amplify a message, but it also risks reducing complex ideas to soundbites, stripping them of nuance and personal reflection.

Consider the process of forming political beliefs as a moral responsibility. Adopting a stance without understanding its historical context, underlying principles, or potential consequences can lead to shallow engagement with critical issues. For example, a teenager might parrot their parents’ views on climate policy without researching the science or considering alternative perspectives. While this behavior is not plagiarism in the traditional sense, it raises ethical concerns about intellectual honesty and the duty to think critically. Borrowing views without scrutiny undermines the democratic ideal of informed citizenship, turning political discourse into an echo chamber of unexamined ideas.

To navigate the ethics of borrowing political views, individuals should adopt a three-step approach. First, question the source: Is the view rooted in evidence, or is it emotionally charged rhetoric? Second, analyze the context: How does this stance align with broader societal values and historical precedents? Third, personalize the adoption: Reflect on why this view resonates with you and how it fits into your broader worldview. For instance, if you’re drawn to a particular economic theory, study its origins, successes, and failures before integrating it into your beliefs. This method ensures that borrowed views are not mere plagiarism but a thoughtful synthesis of external ideas and personal values.

A cautionary tale emerges when borrowed political views are weaponized for personal gain. Politicians and influencers often adopt stances not out of conviction but to appeal to specific audiences. This strategic borrowing can erode trust in public discourse, as seen in cases where leaders flip-flop on issues for political expediency. For example, a candidate might champion progressive policies during a primary and shift to conservative stances in the general election. Such behavior highlights the ethical pitfalls of adopting views without genuine commitment, turning political beliefs into commodities rather than principles.

Ultimately, the ethics of borrowing political views hinge on intent and accountability. While it is neither practical nor desirable to develop every belief from scratch, individuals must strive to engage meaningfully with the ideas they adopt. Treating political stances as intellectual property misses the point; the real issue is the moral obligation to think critically and act authentically. By acknowledging the sources of our beliefs, questioning their validity, and personalizing their adoption, we can borrow responsibly, enriching our political discourse rather than diluting it. This approach ensures that borrowed views are not plagiarized opinions but stepping stones toward a more informed and principled engagement with the world.

Navigating Political Careers: Strategies for Success in Public Service

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

It is not plagiarism to share or discuss someone else's political opinions, as ideas themselves cannot be copyrighted. However, you must properly cite the source if you are directly quoting or paraphrasing their specific words or arguments.

No, claiming someone else's political analysis or arguments as your own without proper attribution is considered plagiarism, even if the topic is political opinions. Always give credit to the original author or source.

Political opinions themselves are not protected by intellectual property laws, as they are considered part of the public discourse. However, the specific expression of those opinions (e.g., written articles, speeches) may be copyrighted, and using them without permission or attribution could be plagiarism.