Political activity encompasses a broad range of actions and behaviors aimed at influencing government policies, decision-making processes, or public opinion. It includes, but is not limited to, voting, campaigning, lobbying, protesting, and engaging in public discourse on political issues. Individuals, groups, or organizations may participate in political activity through formal channels, such as joining political parties or running for office, or through informal means, like social media advocacy or community organizing. What constitutes political activity can vary by context and jurisdiction, as laws and norms differ across countries, often defining permissible actions for citizens, corporations, and non-governmental entities. Understanding the scope of political activity is crucial for navigating the complexities of civic engagement and ensuring compliance with legal and ethical standards.

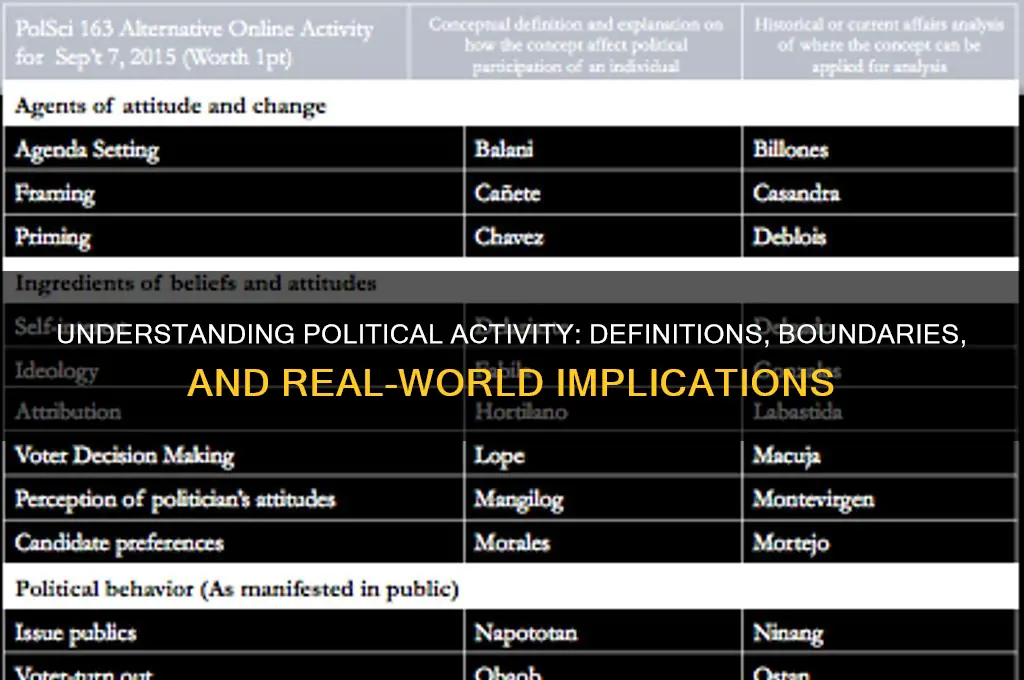

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Actions or behaviors aimed at influencing government policies, decisions, or public opinion. |

| Scope | Includes both formal (e.g., voting, campaigning) and informal (e.g., protests, social media advocacy) activities. |

| Actors | Individuals, groups, organizations, or institutions (e.g., political parties, NGOs, citizens). |

| Intent | To shape political outcomes, advocate for change, or express political beliefs. |

| Methods | Lobbying, campaigning, protesting, voting, media engagement, and public discourse. |

| Platforms | Traditional (e.g., rallies, elections) and digital (e.g., social media, online petitions). |

| Legal Framework | Subject to local, national, or international laws regulating political participation and expression. |

| Impact | Can lead to policy changes, shifts in public opinion, or alterations in political power dynamics. |

| Examples | Running for office, donating to political campaigns, organizing boycotts, or participating in strikes. |

| Non-Partisan vs. Partisan | Can be aligned with specific parties (partisan) or neutral (non-partisan). |

| Global Variations | Definitions and regulations vary by country, influenced by cultural, historical, and legal contexts. |

Explore related products

$20.55

What You'll Learn

- Lobbying and Advocacy: Efforts to influence government policies or decisions through direct communication with officials

- Campaigning and Elections: Activities supporting or opposing candidates, parties, or ballot measures during electoral processes

- Protests and Demonstrations: Public gatherings to express political opinions, demand change, or oppose actions

- Political Donations: Financial contributions to candidates, parties, or organizations to support political goals

- Policy Development: Research, drafting, and promoting specific legislative or regulatory proposals

Lobbying and Advocacy: Efforts to influence government policies or decisions through direct communication with officials

Lobbying and advocacy are the lifeblood of democratic systems, serving as direct channels for individuals, corporations, and organizations to shape government policies. Unlike voting, which is periodic and limited in scope, lobbying allows for continuous engagement with policymakers. It involves strategic communication with officials—legislators, regulators, and executives—to advocate for specific outcomes. This process is not confined to Capitol Hill or Parliament; it occurs in local councils, state legislatures, and international bodies. The key lies in persistence and precision: knowing whom to approach, what to ask for, and how to frame the argument. For instance, a nonprofit advocating for climate legislation might target members of an environmental committee, armed with data on economic benefits and voter sentiment.

Effective lobbying requires a structured approach. First, identify the decision-makers whose votes or signatures are critical. Research their priorities, past votes, and constituencies to tailor your message. Second, craft a clear, concise ask—whether it’s amending a bill, allocating funds, or blocking a regulation. Third, leverage multiple channels: in-person meetings, letters, social media campaigns, and coalition-building. For example, a tech company opposing a data privacy bill might mobilize its employees to contact their representatives, while simultaneously publishing op-eds highlighting job losses. Caution: transparency is non-negotiable. Failure to disclose lobbying efforts can lead to legal repercussions and public backlash, as seen in scandals involving undisclosed foreign lobbying.

Advocacy, while similar to lobbying, often carries a grassroots or public-interest focus. It thrives on mobilizing communities to amplify a message. Consider the success of the ACLU in challenging immigration policies: they combined legal action with public demonstrations and media campaigns to pressure lawmakers. Advocacy groups often use storytelling to humanize issues, such as sharing testimonials from affected individuals. However, advocacy without direct lobbying can lack impact. For instance, a campaign to raise awareness about mental health funding may gain traction on social media but fail to secure budget increases without targeted meetings with appropriations committees. The takeaway: advocacy and lobbying are most powerful when combined, using public pressure to complement behind-the-scenes negotiations.

A critical distinction in lobbying is the difference between *inside* and *outside* strategies. Inside lobbying involves direct contact with officials, often through registered lobbyists who navigate legislative processes. Outside lobbying, on the other hand, targets the public to indirectly influence policymakers. For example, a pharmaceutical company might fund ads highlighting the dangers of drug price caps, aiming to sway public opinion and, consequently, congressional votes. While outside lobbying can be effective, it risks appearing manipulative if not executed carefully. A 2020 study found that 62% of voters distrust campaigns funded by corporate interests, underscoring the need for authenticity. Practical tip: align outside efforts with genuine public concerns, such as framing a tax policy debate around fairness rather than corporate profits.

Finally, lobbying and advocacy are not without ethical pitfalls. The line between persuasion and coercion can blur, especially when financial contributions or campaign support are involved. To maintain integrity, establish clear boundaries: avoid quid pro quo arrangements and prioritize long-term relationships over transactional exchanges. For nonprofits, this might mean diversifying funding sources to avoid dependence on a single donor. Corporations can adopt transparency policies, such as publicly disclosing lobbying expenditures and meeting minutes. Ultimately, the goal is to influence policy while upholding democratic values. Done right, lobbying and advocacy are not just tools for the powerful but mechanisms for ensuring that diverse voices are heard in the halls of power.

Alan Jackson's Political Views: Uncovering the Country Star's Stance

You may want to see also

Campaigning and Elections: Activities supporting or opposing candidates, parties, or ballot measures during electoral processes

Campaigning and elections are the lifeblood of democratic processes, serving as the primary arena where political activity manifests in tangible, outcome-driven ways. At its core, this activity revolves around mobilizing support or opposition for candidates, political parties, or ballot measures. Unlike broader political engagement, such as advocacy or lobbying, campaigning is time-bound, intensely focused, and directly tied to electoral outcomes. It is a high-stakes endeavor where every action—from door-to-door canvassing to multimillion-dollar ad campaigns—is calibrated to sway voter behavior. Understanding this landscape requires dissecting its mechanics, ethical boundaries, and real-world implications.

Consider the tactical diversity of campaign activities. Door-to-door canvassing, for instance, remains one of the most effective methods for voter persuasion, with studies showing a 7-9% increase in turnout among contacted households. Yet, its success hinges on specificity: volunteers must be trained to tailor messages to local concerns, such as healthcare access in rural areas or public transit in urban districts. Contrast this with digital campaigning, where micro-targeted ads on social media platforms can reach niche demographics with surgical precision. A 2020 study found that personalized ads increased candidate favorability by 12% among undecided voters aged 18-34. However, this approach raises ethical questions about data privacy and algorithmic bias, underscoring the dual-edged nature of modern campaign tools.

Oppositional activities, though less glamorous, are equally critical. Ballot measure campaigns often pivot on grassroots efforts to debunk misinformation or highlight unintended consequences. For example, during a 2018 ballot initiative on rent control in California, opponents successfully framed the measure as a threat to housing supply by distributing fact sheets to 500,000 households in high-density districts. This strategy leveraged data analytics to identify and target undecided voters, demonstrating how counter-campaigning requires equal parts creativity and rigor. The takeaway? Effective opposition isn’t about blanket negativity but about strategic messaging grounded in evidence.

Practical tips for engaging in campaign activities abound, but three stand out. First, prioritize local engagement over national trends. A candidate’s stance on climate change, for instance, should be contextualized to regional concerns—flood prevention in coastal areas, job creation in coal-dependent regions. Second, leverage low-cost, high-impact tools like phone banking, which has a 30% higher response rate than email outreach. Finally, adhere to legal boundaries: in the U.S., non-profit organizations must avoid explicit endorsements to maintain tax-exempt status, while PACs face strict contribution limits. Ignoring these rules can derail even the most well-intentioned efforts.

Ultimately, campaigning and elections are a microcosm of democracy’s complexities. They demand a blend of strategic thinking, ethical vigilance, and tactical adaptability. Whether supporting a candidate or opposing a ballot measure, the goal remains the same: to amplify voices and shape outcomes in a way that reflects the collective will. In this arena, every flyer distributed, every ad aired, and every voter contacted is a thread in the larger tapestry of political participation. Master these dynamics, and you don’t just influence an election—you contribute to the health of democracy itself.

Understanding Political Clearance: Definition, Process, and Importance Explained

You may want to see also

Protests and Demonstrations: Public gatherings to express political opinions, demand change, or oppose actions

Protests and demonstrations serve as a direct, visible channel for citizens to voice their political beliefs, often in response to perceived injustices or policy failures. These gatherings can range from small, localized sit-ins to massive marches involving hundreds of thousands of participants. For instance, the 2017 Women’s March mobilized over 5 million people globally, advocating for gender equality and social justice. Such events are not merely acts of dissent; they are strategic tools to amplify marginalized voices and pressure governments or institutions into action. Organizers often employ tactics like chants, signs, and symbolic acts to ensure their message resonates beyond the immediate crowd, leveraging media coverage to reach a broader audience.

Effective protests require careful planning to maximize impact while minimizing risks. Key steps include defining clear objectives, securing permits (where required), and coordinating logistics such as routes, speakers, and safety protocols. For example, the Hong Kong pro-democracy protests in 2019 utilized decentralized leadership and digital tools to maintain momentum despite government crackdowns. However, participants must also be aware of potential legal consequences, such as arrest or fines, and prepare accordingly. Practical tips include wearing comfortable shoes, carrying water, and having a pre-arranged meeting point in case of dispersal. Age-specific considerations are crucial; younger participants may require chaperones, while older individuals should prioritize accessibility and rest breaks.

The effectiveness of protests lies in their ability to create a moral and political dilemma for those in power. By occupying public spaces and disrupting the status quo, demonstrators force authorities to acknowledge their demands. For instance, the 1963 March on Washington, where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his iconic "I Have a Dream" speech, played a pivotal role in advancing civil rights legislation. Comparative analysis shows that protests are most successful when they combine grassroots mobilization with strategic alliances, such as partnerships with labor unions or international organizations. However, their impact is not immediate; sustained pressure, often over months or years, is typically required to achieve tangible policy changes.

Despite their potential, protests are not without challenges. Counter-protests, police violence, and public apathy can undermine their effectiveness. For example, the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests faced both widespread support and intense backlash, highlighting the polarizing nature of such movements. To navigate these obstacles, organizers must focus on maintaining nonviolent discipline, fostering solidarity among participants, and framing their demands in ways that resonate with diverse audiences. Ultimately, protests and demonstrations remain a vital form of political activity, offering a means for ordinary citizens to challenge power structures and shape the course of history.

Understanding Political Leadership Structure: Roles, Hierarchy, and Power Dynamics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$18.59 $19.99

Political Donations: Financial contributions to candidates, parties, or organizations to support political goals

Financial contributions to political candidates, parties, or organizations are a cornerstone of modern political engagement, yet their impact and implications are often misunderstood. At their core, political donations serve as a mechanism for individuals, corporations, and interest groups to influence policy outcomes by supporting those who align with their values or goals. Unlike direct activism or voting, donations provide a quantifiable means of participation, often amplifying the donor’s voice in a system where resources equate to reach. For instance, a $2,900 donation to a federal candidate in the U.S. (the current individual limit per election cycle) can grant access to exclusive events or direct communication channels, illustrating how money translates to access. However, this dynamic raises ethical questions about equity and representation, as those with greater financial means inherently wield disproportionate influence.

Consider the mechanics of political donations: they are not merely transactions but strategic investments. Donors typically assess candidates’ or parties’ viability, policy stances, and potential return on investment before contributing. For example, a tech company might donate to a candidate advocating for deregulation, while environmental organizations fund those pushing for green policies. This strategic nature underscores why transparency is critical. In many jurisdictions, disclosure laws require reporting donations above certain thresholds (e.g., $200 in the U.S. for federal campaigns), allowing the public to scrutinize potential conflicts of interest. Yet, loopholes like dark money—untraceable donations funneled through nonprofits—highlight the challenges of maintaining accountability in this system.

The persuasive power of political donations lies in their ability to shape narratives and outcomes. A well-funded campaign can dominate airwaves, social media, and grassroots mobilization, often tipping the scales in close elections. Take the 2020 U.S. presidential race, where over $14 billion was spent across federal campaigns, dwarfing previous cycles. Such figures demonstrate how financial contributions are not just about supporting a candidate but about securing a seat at the table when policies are crafted. However, this reality also fuels cynicism, as critics argue that donations prioritize the interests of the wealthy over the broader public. To mitigate this, some advocate for public financing of campaigns or stricter donation caps, though such reforms face resistance from those benefiting from the status quo.

Practical considerations for donors include understanding legal limits and tax implications. In the U.S., individuals can contribute up to $5,000 per year to a political action committee (PAC), while corporations and unions are barred from donating directly to candidates but can fund super PACs with no contribution limits. Donors should also research recipients’ track records and alignment with their values, as contributions become part of the public record and can reflect on the donor’s reputation. For those wary of direct donations, alternative forms of political activity—like volunteering, advocacy, or supporting nonpartisan voter education—offer ways to engage without financial commitment. Ultimately, political donations are a double-edged sword: a tool for participation that demands scrutiny to ensure democracy remains inclusive and equitable.

Shakespeare's Political Pen: Unveiling the Bard's Hidden Agenda in Plays

You may want to see also

Policy Development: Research, drafting, and promoting specific legislative or regulatory proposals

Policy development is the backbone of political activity, transforming abstract ideas into tangible legislative or regulatory frameworks. At its core, this process involves meticulous research, strategic drafting, and targeted promotion. Each phase demands precision, collaboration, and a deep understanding of the socio-political landscape. Without effective policy development, even the most well-intentioned initiatives risk becoming hollow promises or unimplementable mandates.

Consider the research phase as the foundation of policy development. This stage requires gathering data, analyzing trends, and consulting stakeholders to identify gaps or inefficiencies in existing systems. For instance, drafting a healthcare policy might involve examining patient outcomes, insurance coverage rates, and provider feedback. Tools like surveys, focus groups, and statistical analysis are invaluable here. A common pitfall is relying solely on secondary data; primary research, such as interviews with affected communities, often uncovers nuances that shape more equitable policies. Practical tip: Allocate at least 40% of your development timeline to research to ensure a robust evidence base.

Drafting the policy is where research meets action. This step demands clarity, specificity, and alignment with broader legislative or regulatory goals. A well-drafted proposal avoids vague language, incorporates measurable outcomes, and anticipates potential challenges. For example, a climate policy might outline emission reduction targets, funding mechanisms, and enforcement protocols. Caution: Overloading the text with jargon alienates stakeholders and complicates implementation. Instead, use plain language and include a glossary for technical terms. Pro tip: Test the draft with a diverse group of stakeholders to identify ambiguities or unintended consequences.

Promoting the policy is as critical as its creation. Effective advocacy requires tailoring the message to different audiences—lawmakers, industry leaders, and the public—while highlighting its benefits and addressing concerns. Social media campaigns, op-eds, and coalition-building are powerful tools. For instance, a policy promoting renewable energy might emphasize job creation for lawmakers and cost savings for the public. Comparative analysis shows that policies backed by broad coalitions are 30% more likely to gain legislative approval. Practical advice: Develop a promotion timeline that aligns with legislative calendars to maximize impact.

In conclusion, policy development is a dynamic, multi-stage process that bridges the gap between vision and reality. By prioritizing rigorous research, clear drafting, and strategic promotion, policymakers can craft proposals that resonate and endure. Each phase builds on the last, requiring adaptability and a commitment to public good. Done right, this process not only shapes laws but also transforms societies.

Understanding Politics: David Easton's Definition and Its Modern Relevance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political activity includes actions or efforts aimed at influencing government policies, elections, legislation, or public opinion on political matters. This can involve campaigning, lobbying, donating to political parties, or advocating for specific issues.

Yes, voting in an election is a form of political activity as it directly participates in the democratic process by choosing representatives or deciding on policies.

Yes, sharing political opinions on social media can be considered political activity if it aims to influence others’ views, promote a candidate, or advocate for a specific policy or cause.

Not always. Donations to non-profits are only considered political activity if the organization engages in lobbying, advocacy, or other efforts to influence government policies or elections.

Yes, attending a protest or rally is typically considered political activity, as it involves public demonstration to advocate for or against specific political issues, policies, or government actions.