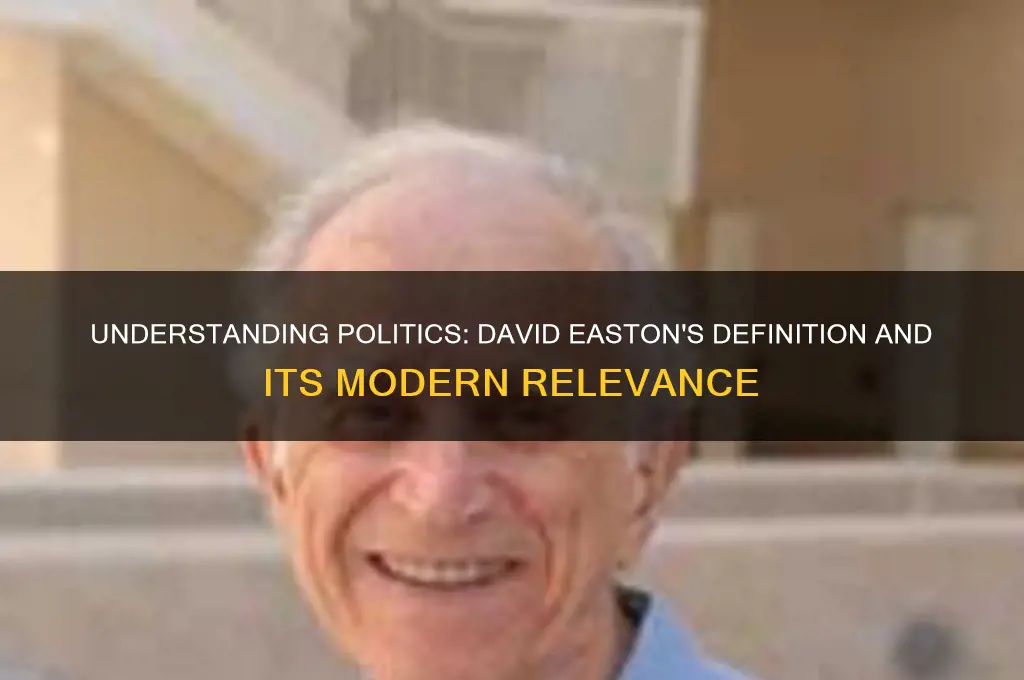

David Easton, a prominent political scientist, defines politics as the authoritative allocation of values in a society. This definition, central to his systems theory of politics, emphasizes the processes through which societies make binding decisions about the distribution of resources, power, and norms. Easton argues that politics is not merely about conflict or competition but also involves the creation and maintenance of order, stability, and consensus within a social system. His framework highlights the dynamic interplay between inputs (demands and supports from the public) and outputs (policy decisions and actions by the government), illustrating how political systems adapt to changing environments to ensure their survival and legitimacy. By focusing on the authoritative allocation of values, Easton’s perspective provides a comprehensive understanding of politics as a fundamental mechanism for managing societal interests and maintaining collective well-being.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Authoritative Allocation of Values | Politics involves the authoritative allocation of values for a society, meaning it determines who gets what, when, and how. This includes the distribution of resources, rights, and privileges. |

| Collective Decision-Making | It emphasizes the process of making decisions that affect the entire community or society, often through institutions like governments. |

| Conflict Resolution | Politics serves as a mechanism to manage and resolve conflicts over scarce resources and differing interests within a society. |

| Power and Influence | Central to politics is the exercise of power and influence to shape policies, norms, and behaviors in society. |

| Public Goods Provision | It involves the provision of public goods and services that benefit the entire society, such as infrastructure, education, and healthcare. |

| Legitimacy and Authority | Politics establishes and maintains the legitimacy of governing institutions and authorities, ensuring their acceptance by the populace. |

| Policy Formulation and Implementation | It encompasses the creation, adoption, and execution of policies that address societal issues and needs. |

| Social Integration | Politics plays a role in integrating diverse groups within a society, fostering cohesion and shared identity. |

| Adaptation and Change | It facilitates societal adaptation to changing circumstances, both internally and externally, through policy adjustments and reforms. |

| Normative and Empirical Dimensions | Politics combines normative concerns (what ought to be) with empirical realities (what is), balancing ideals with practical constraints. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Systematic Analysis: Easton’s focus on studying politics as a system with inputs and outputs

- Political System: Definition and role of the political system in society

- Inputs and Outputs: How demands, support, and decisions shape political processes

- Feedback Mechanism: The role of feedback in maintaining system stability and adaptation

- Behavioral Approach: Easton’s shift from institutions to political behavior and dynamics

Systematic Analysis: Easton’s focus on studying politics as a system with inputs and outputs

David Easton's systematic approach to studying politics revolutionized the field by treating it as a dynamic, interdependent system. At its core, this framework identifies inputs—demands and supports from society—and outputs—the policies and actions produced by the political system. This lens allows scholars to analyze how societies articulate their needs and how governments respond, creating a feedback loop that sustains or challenges the system's stability. For instance, public protests (an input) might demand policy changes (an output), which in turn shape future public attitudes and behaviors.

To apply Easton’s model effectively, begin by mapping the inputs within a given political context. These can range from voter preferences and interest group pressures to economic crises or cultural shifts. Next, trace how these inputs are processed through institutions like legislatures, courts, or bureaucracies. The outputs—laws, regulations, or public programs—then become the focus of analysis. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, public fear and economic demands (inputs) led to lockdowns and stimulus packages (outputs), which subsequently influenced public trust in government.

A critical caution when using this framework is avoiding oversimplification. Easton’s system is not linear; feedback mechanisms complicate the process. Outputs often generate new inputs, creating cycles of adaptation or conflict. For instance, a policy to reduce carbon emissions (output) might face resistance from industries (new input), forcing policymakers to recalibrate their approach. Recognizing these feedback loops is essential for accurate analysis.

Easton’s systematic analysis also highlights the importance of studying political efficacy—the belief that one’s actions can influence the system. High efficacy amplifies inputs, as citizens engage more actively, while low efficacy dampens them. For practitioners, this means fostering civic engagement through education, transparency, and accessible participation channels. A practical tip: policymakers can enhance efficacy by creating platforms for public input, such as town halls or online forums, ensuring that citizen demands are heard and addressed.

In conclusion, Easton’s focus on inputs and outputs provides a structured yet flexible tool for understanding political dynamics. By systematically analyzing how demands become policies and how those policies reshape demands, scholars and practitioners can navigate complex political landscapes. This approach not only deepens theoretical insights but also offers actionable strategies for improving governance and civic engagement.

Understanding NYC Politics: A Comprehensive Guide to the City's Political Landscape

You may want to see also

Political System: Definition and role of the political system in society

David Easton, a prominent political scientist, defines politics as the authoritative allocation of values in a society. This definition underscores the role of political systems in determining how resources, power, and norms are distributed and enforced. A political system, therefore, is the framework through which this allocation occurs, encompassing institutions, processes, and norms that govern decision-making and conflict resolution. It is not merely a collection of rules but a dynamic mechanism that shapes societal outcomes.

Consider the analogy of a human body: just as the circulatory system ensures the distribution of oxygen and nutrients, a political system ensures the distribution of power and resources. In democracies, this distribution is often mediated through elections and representative bodies, while in authoritarian regimes, it may be centralized in the hands of a single leader or elite group. The effectiveness of a political system hinges on its ability to adapt to societal needs, manage conflicts, and maintain legitimacy. For instance, the U.S. political system, with its checks and balances, is designed to prevent the concentration of power, whereas China’s system prioritizes stability and centralized control.

The role of a political system extends beyond governance; it also reflects and reinforces societal values. In Sweden, the political system emphasizes equality and welfare, as evidenced by its robust social safety nets and progressive taxation. Conversely, in Singapore, the system prioritizes efficiency and order, with strict laws and a technocratic approach to policy-making. These examples illustrate how political systems are not neutral but are deeply intertwined with the cultural, economic, and historical contexts of their societies.

To understand the practical implications, consider the following steps: first, identify the core institutions of a political system (e.g., legislature, judiciary, executive). Second, analyze how these institutions interact to allocate values. Third, evaluate the system’s responsiveness to societal demands. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, political systems worldwide were tested on their ability to mobilize resources and implement policies swiftly. Democracies like New Zealand succeeded through transparent communication and public trust, while others struggled due to bureaucratic inefficiencies or political polarization.

A critical takeaway is that no political system is universally superior; each is a product of its environment and serves specific purposes. However, all effective systems share common traits: they are inclusive, accountable, and adaptable. For individuals, understanding one’s political system is essential for meaningful participation. Practical tips include staying informed about policy changes, engaging in local governance, and advocating for reforms that align with societal needs. Ultimately, a political system’s success is measured not by its structure but by its ability to foster justice, stability, and progress.

Do Kids Grasp Politics? Exploring Children's Political Awareness and Understanding

You may want to see also

Inputs and Outputs: How demands, support, and decisions shape political processes

Political systems, as David Easton famously conceptualized, function as dynamic processes of transformation, where inputs—such as demands and support—are converted into outputs in the form of decisions and policies. This framework highlights the interplay between citizens and their government, revealing how societal pressures and resources shape political outcomes. For instance, consider a community demanding stricter environmental regulations. This demand is an input, fueled by public concern over pollution. The government’s response—whether to enact new laws or ignore the issue—is the output, which in turn influences future inputs, such as increased support or disillusionment.

To understand this process, imagine a three-step mechanism: identification, translation, and action. First, demands must be identified. These can range from calls for healthcare reform to protests against taxation. Second, these demands are translated into actionable agendas through political institutions, such as legislative committees or executive agencies. Third, decisions are made, resulting in policies or actions. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, public demands for vaccine access were identified, translated into distribution plans, and acted upon through mass vaccination campaigns. The effectiveness of this process depends on the system’s capacity to absorb and process inputs, which varies across democracies, autocracies, and hybrid regimes.

A critical factor in this transformation is the role of support, which acts as both an input and a resource. Support can take the form of voter turnout, party membership, or financial contributions. In the 2020 U.S. presidential election, record-breaking campaign donations and grassroots mobilization were inputs that influenced the outcome. However, support is not neutral; it often reflects power imbalances. Wealthy interest groups, for instance, may provide disproportionate support, skewing outputs in their favor. This raises questions about equity: whose demands are prioritized, and whose support carries more weight?

Caution must be exercised when analyzing this framework, as it oversimplifies complexities. Not all inputs lead to outputs; some demands are ignored or suppressed. For example, marginalized communities often face barriers in having their voices heard, leading to systemic exclusion. Additionally, outputs are not always linear responses to inputs. Governments may preempt demands by proactively addressing issues or manipulate inputs through propaganda. Take China’s response to labor rights demands: instead of yielding to worker protests, the government has often prioritized economic stability, illustrating how outputs can reflect ideological priorities over public demands.

In practical terms, understanding this input-output dynamic empowers citizens to engage more strategically. Advocacy groups, for instance, can amplify their demands by leveraging multiple inputs—petitions, media campaigns, and lobbying—to increase their chances of influencing outputs. Policymakers, on the other hand, must ensure that the translation process is transparent and inclusive to maintain legitimacy. For example, participatory budgeting in cities like Porto Alegre, Brazil, directly involves citizens in deciding how public funds are allocated, aligning outputs more closely with diverse inputs.

Ultimately, the Easton model serves as a lens for dissecting political processes, but its utility lies in its application. By examining how demands, support, and decisions interact, we can identify levers for change and anticipate outcomes. Whether advocating for reform or crafting policy, recognizing this dynamic ensures that political systems remain responsive to the needs of those they serve. After all, politics is not just about power—it’s about the continuous negotiation between what people want and what governments deliver.

Bob's Red Mill: Uncovering Political Ties and Brand Values

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Feedback Mechanism: The role of feedback in maintaining system stability and adaptation

Feedback mechanisms are the lifeblood of political systems, ensuring their survival and evolution. David Easton's conceptualization of politics as a system of interactions between inputs and outputs highlights the critical role of feedback in maintaining stability and enabling adaptation. When citizens demand policy changes, for instance, their voices act as feedback, signaling dissatisfaction with the current state of affairs. This feedback, if effectively processed, triggers adjustments within the political system, such as legislative reforms or shifts in administrative priorities. Without this mechanism, systems become rigid, unresponsive, and ultimately unsustainable.

Consider the analogy of a thermostat regulating room temperature. Just as the thermostat receives feedback from the environment and adjusts the heating or cooling system accordingly, political systems rely on feedback to calibrate their responses. Public opinion polls, elections, and protests serve as sensors, detecting deviations from societal expectations. For example, a government facing widespread protests over economic inequality might introduce progressive taxation or social welfare programs as corrective measures. This adaptive process not only restores equilibrium but also strengthens the system's resilience by demonstrating its capacity to learn and evolve.

However, the effectiveness of feedback mechanisms hinges on their quality and the system's willingness to act upon them. In some cases, feedback may be distorted or ignored, leading to systemic failures. Authoritarian regimes, for instance, often suppress dissent and manipulate information, rendering feedback mechanisms ineffective. Conversely, in democratic systems, the openness to diverse feedback fosters innovation and accountability. A practical tip for policymakers is to institutionalize feedback channels, such as regular town hall meetings or digital platforms, ensuring that citizen input is systematically collected and analyzed.

The dosage of feedback matters as well. Too little feedback can leave a system blind to emerging challenges, while an overload can lead to paralysis or contradictory responses. Striking the right balance requires strategic prioritization. For instance, age-specific feedback mechanisms—such as youth councils or senior citizen forums—can ensure that the needs of diverse demographic groups are addressed. Additionally, feedback should be actionable; vague or generalized input is less useful than specific, data-driven critiques.

In conclusion, feedback mechanisms are not merely tools for correction but essential drivers of political system vitality. By fostering a culture of responsiveness and incorporating diverse perspectives, systems can navigate complexity and uncertainty with greater agility. As Easton’s framework suggests, politics is inherently dynamic, and feedback is the mechanism that sustains this dynamism. Ignoring or mismanaging feedback, on the other hand, risks stagnation and decline. For practitioners, the takeaway is clear: cultivate robust feedback loops, and the system will thrive.

Tactful Terminology: A Guide to Describing Breasts with Respect and Sensitivity

You may want to see also

Behavioral Approach: Easton’s shift from institutions to political behavior and dynamics

David Easton's behavioral approach marks a pivotal shift in political science, redirecting focus from static institutions to the dynamic, human-driven processes that shape politics. This transition is not merely academic; it reshapes how we understand power, decision-making, and societal interaction. By prioritizing political behavior, Easton reveals that institutions are not self-sustaining entities but outcomes of individual and collective actions. This perspective demands a closer look at the motivations, interactions, and psychological factors influencing political outcomes, offering a more nuanced understanding of how systems evolve and adapt.

To grasp Easton's behavioral approach, consider it as a lens that magnifies the micro-interactions within the macro-political landscape. For instance, instead of analyzing a legislature as a monolithic entity, this approach examines how individual legislators’ beliefs, biases, and strategic behaviors influence policy outcomes. Practical application of this method involves mapping decision-making networks, identifying key influencers, and understanding how information flows within political systems. Researchers can use tools like surveys, observational studies, and network analysis to uncover these dynamics, providing actionable insights for policymakers and activists alike.

One of the strengths of Easton's shift lies in its ability to explain political change. Traditional institutional analysis often struggles to account for rapid shifts in public opinion or policy, but the behavioral approach thrives in this context. Take the rise of social movements, such as climate activism or racial justice campaigns. By focusing on the behaviors of activists, their mobilization strategies, and their interactions with political elites, this approach offers a framework for understanding how grassroots efforts translate into systemic change. For practitioners, this means recognizing the power of individual agency and the importance of fostering collective action.

However, adopting a behavioral lens is not without challenges. It requires a multidisciplinary toolkit, blending political science with psychology, sociology, and even neuroscience. Researchers must navigate the complexity of human behavior, which is often irrational, unpredictable, and context-dependent. For example, while rational choice theory assumes individuals act in self-interest, behavioral studies show that emotions, social norms, and cognitive biases frequently drive political decisions. This complexity underscores the need for rigorous, empirical methods to avoid oversimplification.

In conclusion, Easton's behavioral approach is not just a theoretical shift but a practical guide for dissecting the intricate machinery of politics. It empowers analysts to move beyond surface-level institutional analysis, diving into the human dynamics that underpin political systems. By embracing this perspective, scholars and practitioners can better predict, explain, and influence political outcomes, making it an indispensable tool in the modern study of politics. Whether analyzing policy shifts, social movements, or electoral behavior, this approach reminds us that politics is, at its core, a human endeavor.

COVID-19 Divide: How the Pandemic Became a Political Battleground

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

David Easton defines politics as the authoritative allocation of values within a society. His focus is on how societies make decisions about the distribution of resources, power, and other valued goods, emphasizing the role of authority in this process.

Easton’s systems theory views politics as a dynamic process where inputs (demands and support from society) are transformed into outputs (policy decisions) by the political system. This approach highlights the interaction between the government and the public, emphasizing adaptation and maintenance of stability.

Easton’s definition is influential because it shifts the focus from narrow institutional analysis to a broader understanding of how societies manage conflicts and allocate resources. His systems approach provides a framework for studying political behavior and governance in a holistic manner.