Political leadership structure refers to the organizational framework through which authority, decision-making, and governance are exercised within a political system. It encompasses the roles, hierarchies, and institutions that define how leaders are selected, how power is distributed, and how policies are formulated and implemented. This structure varies widely across different political systems, such as democracies, autocracies, or hybrid regimes, and includes elements like executive branches, legislative bodies, and judicial systems. Understanding political leadership structure is crucial for analyzing how governments function, how accountability is ensured, and how leaders interact with citizens and institutions to shape societal outcomes.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | The organizational framework and hierarchy within a political system. |

| Purpose | To facilitate decision-making, governance, and policy implementation. |

| Types | Presidential, Parliamentary, Authoritarian, Democratic, Hybrid systems. |

| Key Roles | Head of State, Head of Government, Legislature, Judiciary, Bureaucracy. |

| Power Distribution | Centralized (e.g., authoritarian) or Decentralized (e.g., federalism). |

| Decision-Making Process | Consensus-based, Majoritarian, or Autocratic. |

| Accountability | Varies by system; democratic systems emphasize transparency and elections. |

| Stability | Depends on institutional strength, legitimacy, and public trust. |

| Inclusivity | Reflects representation of diverse groups in decision-making processes. |

| Adaptability | Ability to respond to crises, societal changes, and global challenges. |

| Examples | U.S. (Presidential), U.K. (Parliamentary), China (Authoritarian). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Hierarchical Models: Examines traditional top-down structures in political organizations and their impact on decision-making

- Collective Leadership: Explores shared power dynamics, consensus-building, and collaborative governance in political systems

- Authoritarian vs. Democratic: Contrasts centralized control with participatory leadership in political frameworks

- Informal Influence Networks: Analyzes the role of unofficial power brokers and their impact on leadership

- Leadership Succession: Investigates processes and challenges in transferring political power between leaders

Hierarchical Models: Examines traditional top-down structures in political organizations and their impact on decision-making

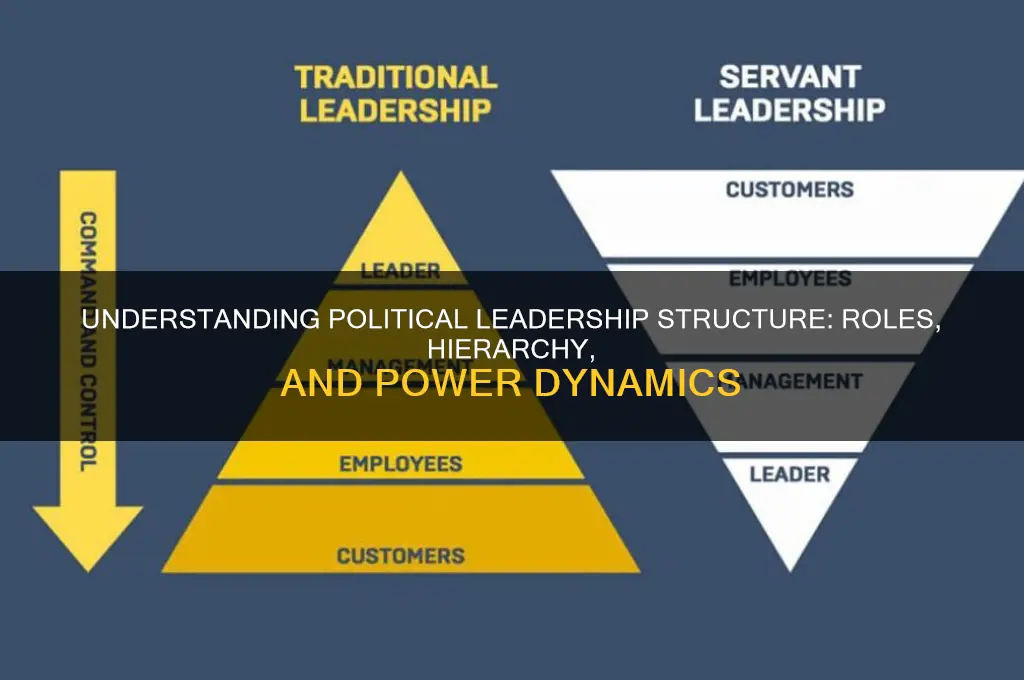

Hierarchical models in political organizations often mirror the structure of a pyramid, with power and authority concentrated at the apex. This top-down approach is exemplified by systems where a single leader or a small executive committee holds ultimate decision-making authority, delegating tasks downward through layers of subordinates. In countries like North Korea, for instance, the Supreme Leader wields absolute power, with lower tiers of government functioning primarily to execute directives. This model ensures unity of command but often stifles dissent and innovation, as decisions flow unidirectionally from the top.

The impact of such structures on decision-making is profound. Hierarchical systems prioritize efficiency and control, enabling swift responses to crises. During the COVID-19 pandemic, authoritarian regimes like China implemented rapid lockdowns and vaccination campaigns, showcasing the advantages of centralized authority. However, this efficiency comes at a cost. Lower-level officials, constrained by rigid chains of command, may lack the autonomy to address local nuances or emerging challenges. For example, in India’s hierarchical bureaucracy, delays in decision-making during the pandemic were attributed to over-reliance on central directives, highlighting the limitations of top-down systems in diverse contexts.

To implement a hierarchical model effectively, organizations must balance central control with localized flexibility. A practical tip is to establish clear communication channels that allow feedback to flow upward, even in rigid structures. For instance, the Singaporean government maintains a hierarchical system but incorporates regular public consultations to ensure policies reflect grassroots concerns. This hybrid approach mitigates the risk of isolation at the top while preserving the efficiency of centralized decision-making.

Despite their historical prevalence, hierarchical models face growing scrutiny in an era of democratization and technological connectivity. Critics argue that such structures are ill-suited to modern challenges, which demand agility, collaboration, and inclusivity. For political organizations considering this model, a cautionary note is in order: over-centralization can lead to decision-making bottlenecks and alienate stakeholders. A comparative analysis of hierarchical and decentralized systems reveals that the former excels in stability but falters in adaptability, suggesting that hybrid models may offer the best of both worlds.

In conclusion, hierarchical models remain a cornerstone of political leadership structures, particularly in contexts requiring swift, unified action. However, their effectiveness hinges on thoughtful implementation and a willingness to incorporate feedback mechanisms. By acknowledging their strengths and limitations, organizations can harness the benefits of hierarchy while avoiding its pitfalls, ensuring decisions are both authoritative and responsive to diverse needs.

Discovering My Political Compass: A Personal Journey of Beliefs and Values

You may want to see also

Collective Leadership: Explores shared power dynamics, consensus-building, and collaborative governance in political systems

In collective leadership, power is distributed among a group rather than concentrated in a single individual, fostering a system where decisions emerge from shared responsibility and collaborative effort. This model contrasts sharply with hierarchical structures, where authority flows downward from a central figure. For instance, Switzerland’s Federal Council operates as a seven-member executive body where decisions are made collectively, and the presidency rotates annually, symbolizing equality and shared governance. This approach minimizes the risk of autocratic decision-making and encourages diverse perspectives to shape policy.

To implement collective leadership effectively, establish clear mechanisms for consensus-building. Begin by defining decision-making thresholds—whether unanimity, supermajority, or simple majority—to ensure alignment without gridlock. Foster open dialogue through structured meetings, such as round-table discussions or deliberative forums, where all voices are heard. For example, in Nordic countries like Sweden and Norway, coalition governments often rely on cross-party negotiations to craft policies, blending competing interests into cohesive solutions. Tools like Robert’s Rules of Order or facilitated mediation can streamline this process, ensuring efficiency without sacrificing inclusivity.

One caution in collective leadership is the potential for diffusion of accountability. When power is shared, responsibility can blur, leading to inaction or blame-shifting. To mitigate this, assign specific roles within the collective, such as a coordinator or spokesperson, to maintain clarity. Additionally, establish performance metrics and regular evaluations to track individual and group contributions. In the European Commission, for instance, each commissioner heads a specific portfolio, ensuring accountability while contributing to collective goals.

The strength of collective leadership lies in its ability to harness diverse expertise and perspectives, but it requires a culture of trust and mutual respect. Invest in team-building activities and conflict resolution training to nurture these qualities. For political parties or organizations adopting this model, start small—pilot collective decision-making in low-stakes scenarios before scaling up. Over time, this approach not only enhances governance but also models democratic values, demonstrating that power shared is power multiplied.

The Ancient Roots of Indian Politics: A Historical Journey

You may want to see also

Authoritarian vs. Democratic: Contrasts centralized control with participatory leadership in political frameworks

Political leadership structures fundamentally shape how power is wielded and decisions are made within a society. At the heart of this distinction lies the contrast between authoritarian and democratic frameworks, each embodying a starkly different approach to governance. Authoritarian regimes prioritize centralized control, concentrating power in the hands of a single leader or small elite group. This model often emphasizes efficiency and order, achieved through top-down decision-making and limited tolerance for dissent. In contrast, democratic systems champion participatory leadership, distributing power among citizens and fostering collective decision-making through mechanisms like voting, public debate, and representative institutions.

Consider the practical implications of these models. In an authoritarian structure, policies are swiftly implemented without the need for widespread consultation, which can lead to rapid infrastructure development or crisis management. However, this efficiency comes at the cost of individual freedoms and the risk of corruption, as checks and balances are often weak. For instance, China’s centralized government has enabled swift economic growth and large-scale projects like the Belt and Road Initiative, but it has also faced criticism for suppressing political opposition and minority rights. Conversely, democratic systems, such as those in Sweden or Canada, prioritize inclusivity and accountability, allowing citizens to influence policy through elections and civil engagement. While this can slow decision-making, it ensures that diverse perspectives are considered, fostering long-term stability and legitimacy.

To illustrate the contrast further, examine the role of leadership in times of crisis. Authoritarian leaders can enact draconian measures with little resistance, as seen in North Korea’s strict COVID-19 lockdowns, which prioritized regime control over public health transparency. Democratic leaders, however, must balance public opinion and constitutional limits, as evidenced by the debates over lockdowns and vaccine mandates in the United States. This comparison highlights a critical trade-off: centralized control offers decisiveness but risks tyranny, while participatory leadership ensures accountability but may struggle with swift action.

For those seeking to understand or implement these structures, a key takeaway is the importance of context. Authoritarian models may appear appealing in unstable regions where quick decision-making is essential, but they often stifle innovation and dissent. Democratic frameworks, while slower, nurture civic engagement and adaptability, making them better suited for diverse, dynamic societies. To navigate this tension, hybrid models—such as Singapore’s blend of strong state control with economic openness—offer a middle ground, though they require careful calibration to avoid tipping into authoritarianism.

Ultimately, the choice between centralized control and participatory leadership hinges on societal values and priorities. Authoritarian systems excel in uniformity and speed but falter in equity and freedom, while democratic systems prioritize inclusivity and accountability at the expense of efficiency. By studying these contrasts, leaders and citizens alike can better design political frameworks that align with their goals, whether stability, growth, or justice. The challenge lies in striking a balance that maximizes the strengths of each approach while mitigating their inherent weaknesses.

Understanding Political Immunity: Legal Protections and Global Implications Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$10.99 $14.95

Informal Influence Networks: Analyzes the role of unofficial power brokers and their impact on leadership

Behind every formal political leadership structure lies a shadow network of informal influence, where unofficial power brokers wield significant control. These individuals, often operating outside official hierarchies, shape decisions, sway opinions, and redirect resources through personal relationships, expertise, or strategic positioning. Their impact is subtle yet profound, as they bridge gaps between formal institutions and grassroots realities, often determining the success or failure of leadership initiatives.

Consider the role of lobbyists, community organizers, or even social media influencers in modern politics. These actors lack formal titles but possess the ability to mobilize constituencies, frame narratives, or secure funding for specific agendas. For instance, a well-connected business leader might quietly persuade legislators to favor policies benefiting their industry, while a grassroots activist can galvanize public opinion to pressure leaders into action. Such networks thrive on trust, reciprocity, and access to information, often bypassing bureaucratic delays or political gridlock.

Analyzing these networks reveals a paradox: while informal influence can democratize power by amplifying marginalized voices, it can also perpetuate inequality by favoring those with privileged access. A study of urban development projects in emerging economies shows that local power brokers often determine which communities benefit from infrastructure investments, sometimes prioritizing personal interests over public good. This duality underscores the need for transparency and accountability mechanisms to ensure informal influence serves collective goals rather than individual agendas.

To navigate this landscape, leaders must cultivate awareness of these networks, mapping key players and understanding their motivations. Engaging with informal brokers can provide valuable insights into societal needs and political realities, but it requires strategic discernment. Leaders should balance leveraging these networks for policy implementation with safeguarding against undue manipulation. For example, establishing advisory councils that include both formal stakeholders and informal influencers can create a structured yet flexible dialogue.

Ultimately, informal influence networks are a double-edged sword in political leadership structures. They offer pathways to innovation and inclusivity but also pose risks of corruption and exclusion. By acknowledging their existence and proactively managing their dynamics, leaders can harness their potential while mitigating their pitfalls, fostering governance that is both effective and equitable.

Unveiling Politico's Funding Sources: A Comprehensive Financial Overview

You may want to see also

Leadership Succession: Investigates processes and challenges in transferring political power between leaders

Leadership succession is a critical yet often tumultuous process in political systems, as it determines the continuity and stability of governance. In democratic nations, succession typically follows predetermined rules, such as elections or party nominations, ensuring a peaceful transfer of power. For instance, the United States employs a structured electoral process, while the United Kingdom relies on party leadership contests. In contrast, authoritarian regimes often lack clear mechanisms, leading to power vacuums or internal conflicts. The 2011 Arab Spring highlighted how the absence of succession planning can trigger widespread instability, as seen in Egypt and Libya. Understanding these processes reveals the fragility or resilience of political systems during transitions.

Effective leadership succession requires careful planning and transparency to mitigate challenges. A key step is identifying and grooming potential successors early, as demonstrated by Singapore’s meticulous approach to leadership development. Caution must be exercised to avoid nepotism or favoritism, which can erode public trust. For example, dynastic politics in countries like the Philippines have often led to accusations of corruption and incompetence. Additionally, establishing clear timelines and criteria for succession reduces ambiguity and minimizes power struggles. Practical tips include creating mentorship programs for emerging leaders and instituting term limits to encourage orderly transitions.

One of the most significant challenges in leadership succession is managing the outgoing leader’s influence. In some cases, former leaders retain substantial power, creating dual authority structures that can paralyze decision-making. Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe, for instance, remained a dominant figure even after stepping down, complicating his successor’s ability to govern independently. To address this, institutional reforms can limit post-leadership involvement, such as South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which facilitated Nelson Mandela’s graceful exit. Balancing respect for past leadership with the need for new direction is essential for a smooth transition.

Comparatively, monarchies offer a unique perspective on succession, often relying on hereditary systems. While this provides predictability, it can stifle meritocracy and adaptability. The British monarchy, for example, follows a strict line of succession but has evolved to include modern leadership training for heirs. In contrast, elective monarchies like Malaysia’s rotational system among sultans blend tradition with democratic principles. These examples underscore the importance of tailoring succession processes to cultural and political contexts, ensuring they align with societal values and governance needs.

Ultimately, leadership succession is not merely about replacing individuals but about preserving institutional integrity and public confidence. A successful transition requires a blend of foresight, inclusivity, and adherence to established norms. Countries like Germany and Canada exemplify this by fostering coalition-building and consensus during leadership changes. By studying these models, political systems can develop robust succession frameworks that withstand crises and foster long-term stability. The takeaway is clear: succession planning is not an afterthought but a cornerstone of effective political leadership.

Unsolicited Political Emails: Legal Boundaries and Your Rights Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political leadership structure refers to the organizational framework that defines how power, authority, and decision-making are distributed within a political system, such as a government, party, or organization.

Common types include presidential systems, parliamentary systems, authoritarian regimes, and decentralized models like federalism, each with distinct roles for leaders and institutions.

In a presidential system, the head of state (president) is directly elected and separate from the legislature, while in a parliamentary system, the head of government (prime minister) is typically chosen by and accountable to the legislature.

The structure determines who has the authority to make decisions, how policies are formulated, and the balance of power between branches of government or within political parties.

Yes, political leadership structures can evolve due to constitutional reforms, political revolutions, shifts in power dynamics, or changes in societal demands and governance needs.