A political typology is a systematic framework used to categorize individuals, groups, or ideologies based on their political beliefs, values, and behaviors. It serves as a tool for understanding the complex landscape of political thought by organizing diverse perspectives into distinct types or profiles. These typologies often emerge from surveys, research, and analysis of political attitudes, such as views on government, economics, social issues, and international relations. By grouping people with similar stances, political typologies help identify patterns, predict voting behaviors, and highlight divisions or commonalities within societies. They are widely used in political science, journalism, and polling to simplify and communicate the multifaceted nature of political identities and affiliations.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A political typology categorizes individuals based on their political beliefs, values, and attitudes, often using surveys and data analysis. |

| Purpose | To understand political diversity beyond traditional left-right or partisan divides. |

| Key Dimensions | Role of government, economic policies, social issues, foreign policy, and individual freedoms. |

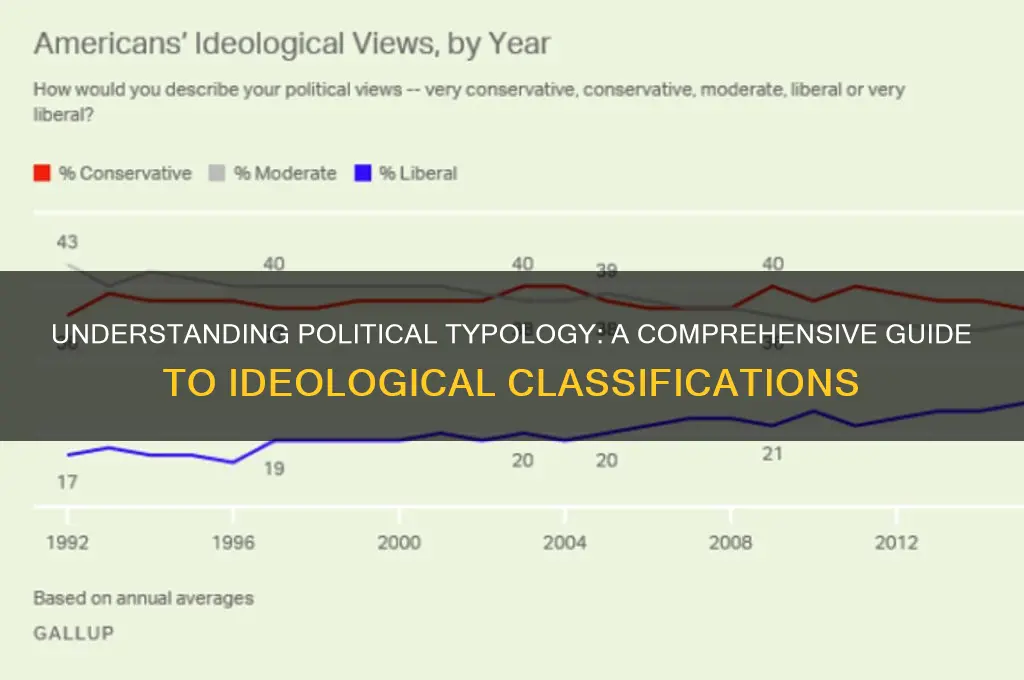

| Examples of Typologies | Pew Research Center's Political Typology, Gallup's political ideology groups. |

| Latest Typology Groups | (Example from Pew 2023): Progressive Left, Establishment Liberals, Moderate Conservatives, Populist Right, etc. |

| Data Sources | Surveys, voter behavior, demographic data, and public opinion polls. |

| Methodology | Cluster analysis, factor analysis, and statistical modeling. |

| Applications | Campaign strategies, policy-making, media analysis, and academic research. |

| Limitations | Over-simplification, evolving political landscapes, and cultural biases. |

| Trends (2023) | Increasing polarization, rise of populist and libertarian groups, and focus on identity politics. |

Explore related products

$28.51 $51.99

What You'll Learn

- Ideological Dimensions: Explains left-right, libertarian-authoritarian, and other key political spectrum axes

- Party Classification: Groups parties by policies, voter base, and historical context

- Voter Profiles: Analyzes demographics, beliefs, and behaviors shaping political identities

- Regime Types: Distinguishes democracies, autocracies, and hybrid systems based on governance

- Theoretical Frameworks: Examines typologies from liberalism, conservatism, socialism, and more

Ideological Dimensions: Explains left-right, libertarian-authoritarian, and other key political spectrum axes

Political typologies often rely on ideological dimensions to map complex beliefs into understandable frameworks. The most familiar of these is the left-right axis, which traditionally contrasts attitudes toward economic equality. The left typically advocates for redistribution of wealth, public services, and progressive taxation, while the right emphasizes free markets, individual enterprise, and limited government intervention. However, this axis is not static; its meaning shifts across cultures and eras. For instance, in the United States, "left" might denote support for social welfare programs, whereas in Europe, it could extend to more radical anti-capitalist positions. Understanding this dimension requires recognizing its context-dependent nuances.

Another critical dimension is the libertarian-authoritarian axis, which focuses on personal freedoms versus state control. Libertarians prioritize individual liberty, minimal regulation, and civil rights, often opposing censorship and surveillance. Authoritarians, by contrast, emphasize order, security, and collective stability, sometimes at the expense of personal freedoms. This axis intersects with the left-right spectrum in complex ways. For example, a libertarian-left position might advocate for both economic equality and personal freedom, while an authoritarian-right stance could support free markets alongside strict social controls. Mapping these intersections reveals the multidimensional nature of political beliefs.

Beyond these two axes, additional dimensions further refine political typologies. The globalist-nationalist axis, for instance, contrasts international cooperation and open borders with sovereignty and cultural preservation. Similarly, the traditionalist-progressive axis divides attitudes toward social norms, with traditionalists favoring established values and progressives pushing for reform. These dimensions are not mutually exclusive; a politician might be economically left-wing, socially progressive, and nationalist, illustrating the need for a multi-axis approach. Each dimension adds granularity, allowing for a more accurate representation of diverse ideologies.

To apply these dimensions effectively, consider them as tools for analysis rather than rigid categories. For example, when evaluating a policy stance, ask: Does it lean left or right economically? Is it libertarian or authoritarian in scope? Does it align with globalist or nationalist principles? This methodical approach helps avoid oversimplification. Practical tip: Use political compass tests or surveys to plot your own beliefs across these axes, but remember that self-assessment can be biased. Cross-reference with external analyses for a more balanced perspective.

In conclusion, ideological dimensions serve as the backbone of political typologies, offering a structured yet flexible way to navigate the complexity of political thought. By mastering the left-right, libertarian-authoritarian, and other key axes, one can decode the nuances of ideologies and predict how they might manifest in policy or behavior. The takeaway is clear: political beliefs are not one-dimensional, and neither should our understanding of them be.

Stepping Away from the Political Arena: A Guide to Quitting Politics

You may want to see also

Party Classification: Groups parties by policies, voter base, and historical context

Political parties are not monolithic entities; they are complex organisms shaped by their policies, the demographics of their supporters, and their historical trajectories. Party classification offers a lens to dissect these layers, grouping parties based on shared characteristics that transcend national boundaries. This approach allows us to identify patterns, predict behaviors, and understand the broader political landscape.

By examining a party's policy platform, we can categorize it along ideological spectra: left-right, libertarian-authoritarian, or populist-technocratic. For instance, a party advocating for wealth redistribution, universal healthcare, and strong labor rights would likely be classified as left-leaning, while one prioritizing free markets, limited government, and individual responsibility would fall on the right.

However, policies alone don't tell the whole story. Voter base analysis adds crucial context. A party's core constituency reveals its priorities and strategies. Consider a party primarily supported by rural, older voters. Its policies might focus on agricultural subsidies, traditional values, and pension reforms, reflecting the needs and concerns of its base. Conversely, a party drawing support from urban, younger voters might prioritize environmental sustainability, social justice, and technological innovation.

Understanding a party's historical context is equally vital. A party born out of a revolutionary movement will likely carry the imprint of its origins, advocating for radical change and challenging established power structures. Conversely, a party with a long history of governing might prioritize stability, pragmatism, and incremental reform.

Classification isn't merely an academic exercise; it has practical implications. It helps voters navigate the political landscape, allowing them to identify parties that align with their values and interests. It also aids in predicting electoral outcomes, as parties with similar classifications often exhibit comparable voting patterns and coalition-building strategies.

To effectively classify parties, consider these steps:

- Identify Key Policy Positions: Analyze party manifestos, public statements, and voting records to pinpoint their stances on core issues like economics, social policy, and foreign affairs.

- Map Voter Demographics: Examine polling data and electoral results to understand the age, gender, socioeconomic status, and geographic distribution of a party's supporters.

- Trace Historical Roots: Research the party's origins, past leaders, and significant events that have shaped its ideology and strategy.

By combining these elements, we can create a nuanced classification system that goes beyond simplistic labels, providing a deeper understanding of the complex world of political parties.

Understanding Political Stumping: Strategies, Impact, and Modern Campaign Techniques

You may want to see also

Voter Profiles: Analyzes demographics, beliefs, and behaviors shaping political identities

Political typologies often begin with voter profiles, which dissect the intricate interplay of demographics, beliefs, and behaviors that mold political identities. For instance, consider the Pew Research Center’s typology, which categorizes voters into groups like "Faith and Flag Conservatives" or "Outsider Left," each defined by age, race, education, and policy preferences. A 35-year-old Hispanic woman with a college degree is statistically more likely to align with progressive policies on immigration and healthcare, while a 60-year-old white male without a degree often leans toward traditionalist values. These profiles aren’t just labels—they’re predictive tools that campaigns use to tailor messaging, allocate resources, and forecast election outcomes.

To construct a voter profile, start by analyzing demographic data: age, gender, income, education, and geographic location. Pair this with behavioral metrics like voting frequency, party affiliation, and engagement with political media. For example, voters aged 18–29 are 40% more likely to engage with political content on social media than those over 65, who prefer traditional news outlets. Beliefs, the third pillar, are assessed through surveys on issues like climate change, gun control, or economic policy. A practical tip: Use cross-tabulation to identify correlations, such as how 70% of urban voters earning over $75,000 annually support public transportation funding, compared to 45% of rural voters in the same income bracket.

Comparatively, voter profiles reveal stark divides. Take the 2020 U.S. election: suburban women shifted toward Democrats due to concerns over healthcare, while rural men solidified Republican support over gun rights. In Europe, Green Party voters are predominantly under 40, urban, and college-educated, contrasting sharply with nationalist party supporters, who skew older and less educated. These differences aren’t just descriptive—they’re actionable. Campaigns can micro-target ads, such as promoting renewable energy policies to young urban voters via Instagram, while emphasizing border security to older rural voters through local radio.

However, constructing voter profiles isn’t without pitfalls. Over-reliance on stereotypes can lead to misclassification. For instance, assuming all young voters are progressive ignores the 25% of millennials who identify as conservative. Additionally, dynamic factors like economic shifts or global events can rapidly alter behaviors. The 2008 financial crisis, for example, pushed many moderate voters toward populist candidates. To mitigate this, update profiles quarterly using real-time data and incorporate qualitative insights from focus groups. A cautionary note: Ethical concerns arise when profiling verges on manipulation, so transparency in data use is critical.

In conclusion, voter profiles are indispensable for understanding the mosaic of political identities. By systematically analyzing demographics, beliefs, and behaviors, they provide a roadmap for engagement. Yet, their power lies not just in categorization but in adaptability. As societies evolve, so must the profiles. Campaigns that refine these tools with precision, ethics, and responsiveness will not only predict voter behavior but also shape the political landscape.

Navigating Political Constraints: Challenges and Strategies for Effective Governance

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Regime Types: Distinguishes democracies, autocracies, and hybrid systems based on governance

Political typologies serve as essential frameworks for understanding the complex landscape of governance, and one of the most fundamental distinctions lies in regime types. At its core, this classification separates political systems into democracies, autocracies, and hybrid regimes, each defined by distinct mechanisms of power distribution and citizen participation. Democracies prioritize popular sovereignty, where power is vested in the people, often through free and fair elections, protection of civil liberties, and an independent judiciary. Autocracies, in contrast, concentrate power in the hands of a single leader, a small group, or a party, typically suppressing political opposition and limiting public participation. Hybrid regimes blur these lines, combining democratic procedures with authoritarian practices, creating a façade of legitimacy while retaining control.

To distinguish these regimes, scholars often employ specific indicators. For democracies, key metrics include competitive elections, freedom of expression, and the rule of law. Autocracies are identified by the absence of these elements, often marked by censorship, repression, and the manipulation of electoral processes. Hybrid systems exhibit a mix, such as holding elections that are technically pluralistic but rigged in favor of the ruling elite. For instance, a country might allow opposition parties to exist but ensure their candidates face insurmountable barriers, such as restrictive campaign laws or state-controlled media. Understanding these nuances is crucial for policymakers, researchers, and citizens alike, as it informs strategies for promoting democratic reforms or countering authoritarian tendencies.

A comparative analysis reveals the practical implications of these regime types. Democracies, while ideal for fostering civic engagement and accountability, can struggle with inefficiency and polarization. Autocracies, though capable of swift decision-making, often lead to human rights abuses and economic inequality. Hybrid regimes, meanwhile, present a unique challenge: they may appear stable but are inherently fragile, as their legitimacy rests on a precarious balance between democratic pretenses and authoritarian control. For example, a hybrid regime might maintain high economic growth rates but face widespread public discontent due to corruption and lack of political freedoms. This duality underscores the importance of context in assessing regime stability and sustainability.

For those seeking to navigate or influence these systems, practical tips can be invaluable. In democracies, focus on strengthening institutions like election commissions and civil society organizations to safeguard against backsliding. In autocracies, prioritize grassroots movements and international pressure to create openings for reform. In hybrid regimes, target specific authoritarian practices, such as media censorship or electoral fraud, while leveraging democratic spaces to build momentum for change. Age categories also play a role: younger populations in autocracies and hybrid systems often drive demands for greater freedoms, while older generations may prioritize stability. Tailoring strategies to these dynamics can enhance the effectiveness of efforts to promote democratic governance or resist authoritarian consolidation.

Ultimately, the distinction between democracies, autocracies, and hybrid regimes is not merely academic but has profound real-world implications. It shapes how citizens experience governance, how states interact on the global stage, and how international norms evolve. By understanding these regime types, stakeholders can better diagnose challenges, identify opportunities, and craft interventions that align with local contexts and global standards. Whether analyzing a country’s political trajectory or advocating for change, this typology provides a critical lens for navigating the complexities of modern governance.

Understanding Political Praxis: Theory, Action, and Social Transformation Explained

You may want to see also

Theoretical Frameworks: Examines typologies from liberalism, conservatism, socialism, and more

Political typologies serve as lenses through which ideologies are categorized, compared, and understood. Among the most prominent frameworks are liberalism, conservatism, and socialism, each offering distinct principles and priorities. Liberalism, rooted in individual liberty and equality, emphasizes personal freedoms, free markets, and limited government intervention. Conservatism, by contrast, prioritizes tradition, stability, and hierarchical structures, often advocating for strong national identity and moral order. Socialism focuses on collective welfare, economic equality, and public ownership of resources, challenging capitalist systems. These typologies are not rigid but rather spectra, allowing for variations like social liberalism, fiscal conservatism, or democratic socialism. Understanding their core tenets is the first step in navigating their complexities.

To analyze these frameworks effectively, consider their responses to key societal issues. For instance, liberalism typically supports progressive policies like LGBTQ+ rights and climate action, while conservatism may resist such changes in favor of preserving established norms. Socialism, meanwhile, critiques both by advocating for systemic redistribution of wealth and resources. A practical exercise is to map these ideologies onto real-world policies: universal healthcare aligns with socialist principles, deregulation with liberalism, and law-and-order policies with conservatism. This comparative approach reveals not only their differences but also their overlaps, such as when liberal democracies adopt socialist welfare programs.

When constructing a typology, beware of oversimplification. Each framework contains internal debates and regional variations. For example, European conservatism often includes robust social safety nets, unlike its American counterpart. Similarly, socialism ranges from democratic models in Scandinavia to authoritarian regimes in history. To avoid misclassification, ground your analysis in historical context and empirical data. Tools like political compass tests can help individuals identify their leanings but should be supplemented with deeper study to grasp nuances.

A persuasive argument for typologies lies in their utility for dialogue and policy-making. By framing debates within these frameworks, stakeholders can identify common ground or irreconcilable differences. For instance, a liberal and a socialist might both critique corporate power but diverge on solutions—regulation versus nationalization. This clarity fosters more productive discussions than vague ideological labels. Policymakers can also use typologies to design inclusive policies, such as blending conservative values with socialist programs to gain broader support.

In conclusion, theoretical frameworks like liberalism, conservatism, and socialism provide essential tools for deciphering political landscapes. Their examination requires a balance of abstraction and specificity, recognizing both their universal principles and contextual adaptations. By mastering these typologies, one gains not just knowledge but a strategic lens for engaging with the complexities of governance and society. Start with foundational texts, apply them to contemporary issues, and continually refine your understanding through interdisciplinary exploration.

United Beyond Politics: Bridging Divides for a Stronger, Inclusive Community

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political typology is a classification system that categorizes individuals or groups based on their political beliefs, values, and attitudes. It helps to organize and understand the diversity of political perspectives within a population.

A political typology is typically created through surveys, data analysis, and statistical methods. Researchers identify key political dimensions (e.g., liberal vs. conservative, libertarian vs. authoritarian) and group respondents based on their responses to questions related to these dimensions.

A political typology is important because it provides insights into the complexities of political opinions, helps identify trends, and allows for more nuanced analysis of voter behavior, public opinion, and political polarization.

Political typologies are not static; they can evolve as societal values, issues, and demographics shift. Researchers often update typologies to reflect new political dynamics and emerging groups within the population.