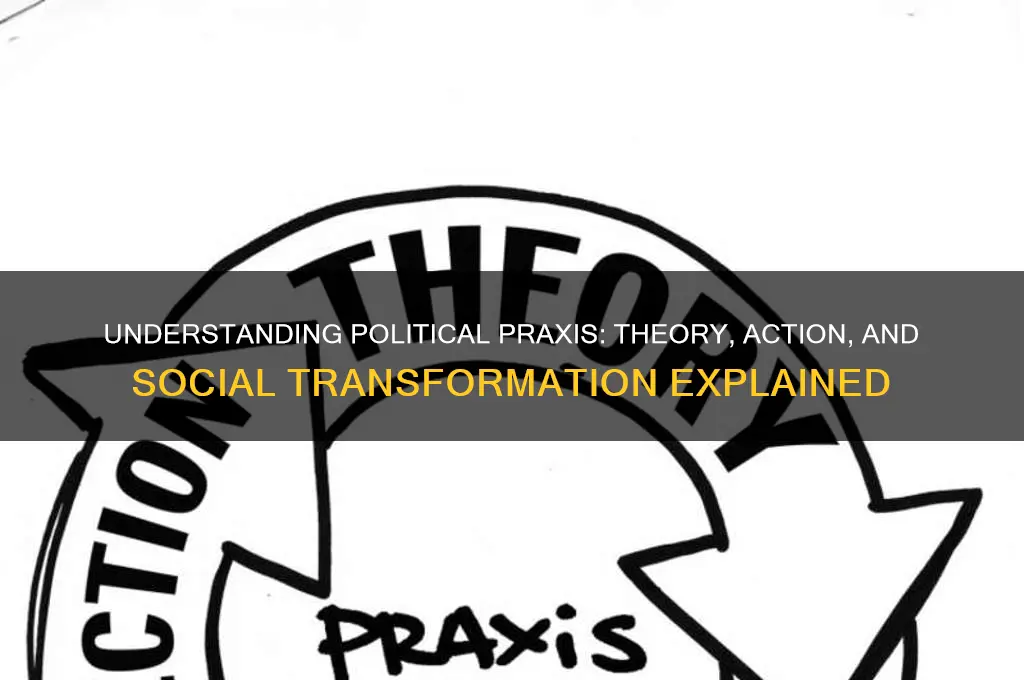

Political praxis refers to the practical application of political theory and ideology in real-world actions and movements. Rooted in the Greek word *praxis*, meaning action or practice, it bridges the gap between abstract ideas and concrete political change. Unlike purely academic or theoretical approaches, political praxis emphasizes engagement, activism, and the transformation of societal structures through deliberate, purposeful action. It is often associated with critical theory, Marxism, and liberation movements, where the goal is not just to understand power dynamics but to challenge and reshape them. At its core, political praxis involves reflection, collective organizing, and strategic intervention to achieve justice, equality, and systemic reform.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Action-Oriented | Emphasizes practical action over mere theory or discussion. |

| Transformative | Aims to bring about systemic change in political, social, or economic structures. |

| Grounded in Theory | Rooted in philosophical, ideological, or theoretical frameworks (e.g., Marxism, feminism). |

| Collective | Focuses on collective efforts rather than individual actions. |

| Contextual | Tailored to specific historical, cultural, and socio-political contexts. |

| Reflective | Involves continuous reflection and adaptation based on outcomes and feedback. |

| Empowering | Seeks to empower marginalized or oppressed groups. |

| Intersectional | Addresses overlapping systems of oppression (e.g., race, class, gender). |

| Sustainable | Aims for long-term, sustainable change rather than short-term gains. |

| Democratic | Promotes participatory decision-making and inclusivity. |

| Critical | Challenges dominant power structures and ideologies. |

| Educational | Involves raising awareness and educating communities about political issues. |

| Adaptive | Flexible and responsive to changing circumstances and challenges. |

| Ethical | Guided by principles of justice, equality, and human rights. |

| Global and Local | Balances global perspectives with local realities and needs. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Theory vs. Practice: Bridging the gap between political ideas and real-world implementation for meaningful change

- Collective Action: Mobilizing communities to challenge power structures and achieve shared political goals

- Ideology in Praxis: Applying political philosophies (e.g., Marxism, liberalism) to everyday struggles

- Grassroots Organizing: Building local movements to address systemic issues and empower marginalized groups

- Critique of Praxis: Evaluating the effectiveness and limitations of political actions and strategies

Theory vs. Practice: Bridging the gap between political ideas and real-world implementation for meaningful change

Political praxis, the fusion of theory and practice, demands more than intellectual rigor—it requires actionable strategies to translate ideals into tangible outcomes. Consider the paradox of democratic socialism: while its theoretical framework promises equitable wealth distribution, its implementation often falters due to bureaucratic inefficiencies and resistance from entrenched power structures. For instance, Nordic countries like Sweden and Denmark have successfully bridged this gap by pairing progressive taxation with robust social safety nets, proving that theory can thrive in practice when adapted to local contexts and supported by institutional frameworks.

To bridge the theory-practice divide, begin by identifying the specific mechanisms needed to operationalize political ideas. Take the concept of participatory budgeting, where citizens directly allocate public funds. In Porto Alegre, Brazil, this theory was implemented through a structured process: community assemblies, delegate elections, and project prioritization. The key takeaway? Successful praxis requires clear procedural steps, stakeholder engagement, and iterative feedback loops to ensure alignment between vision and execution.

However, even the most well-designed strategies face obstacles. Ideological purity can hinder adaptability, as seen in rigid Marxist-Leninist regimes that prioritized dogma over practical solutions. Conversely, pragmatism without a guiding theory risks becoming directionless, as evidenced by technocratic policies that prioritize efficiency over equity. The challenge lies in balancing fidelity to core principles with the flexibility to navigate real-world complexities—a delicate equilibrium that demands constant negotiation and compromise.

A persuasive argument for bridging this gap lies in the urgency of addressing global crises. Climate change, for instance, cannot be tackled through theoretical frameworks alone. The Green New Deal exemplifies praxis in action: it combines scientific consensus (theory) with policy prescriptions like renewable energy subsidies and job retraining programs (practice). To replicate such success, advocates must ground their proposals in empirical evidence, build cross-sector coalitions, and communicate benefits in terms of immediate, measurable impact.

Ultimately, the essence of political praxis is not just to theorize or act, but to iterate. The Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. provides a blueprint: leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X adapted their strategies based on real-time feedback, shifting from nonviolent protests to more assertive tactics as circumstances demanded. For practitioners today, this means embracing failure as a learning opportunity, prioritizing inclusivity to amplify diverse voices, and leveraging technology to scale solutions. The gap between theory and practice is not a chasm but a bridge—one built through intentionality, resilience, and a commitment to meaningful change.

Understanding the GOP: A Comprehensive Guide to the Political Party

You may want to see also

Collective Action: Mobilizing communities to challenge power structures and achieve shared political goals

Political praxis is the fusion of theory and practice in the pursuit of social and political change. Collective action stands as its cornerstone, transforming individual grievances into a force capable of dismantling entrenched power structures. Consider the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, where grassroots organizing, mass protests, and strategic boycotts coalesced to challenge systemic racism and secure legislative victories. This historical example underscores the power of collective action: when communities unite around shared goals, they amplify their voices and create pathways for meaningful transformation.

Mobilizing communities for collective action requires more than shared discontent—it demands intentional strategies. Start by identifying a clear, unifying goal that resonates with the community’s lived experiences. For instance, a campaign to improve public transportation in underserved neighborhoods might begin with surveys and town halls to pinpoint specific needs. Next, build diverse coalitions that include local leaders, activists, and organizations to ensure broad representation and resource pooling. Leverage both traditional methods (e.g., door-to-door outreach) and digital tools (e.g., social media campaigns) to sustain momentum. Remember, successful collective action thrives on inclusivity, transparency, and adaptability to evolving circumstances.

One of the greatest challenges in collective action is maintaining solidarity in the face of power structures designed to divide. Ruling elites often employ tactics like co-optation, repression, or misinformation to fracture movements. To counter this, foster internal trust through open communication and shared decision-making processes. For example, the Zapatista movement in Mexico prioritized horizontal leadership and consensus-building, ensuring that no single voice dominated. Additionally, educate participants on the history of resistance movements to provide context and resilience. By understanding these dynamics, communities can anticipate challenges and develop strategies to stay united and focused.

Finally, collective action is not a one-time event but a sustained process requiring patience and persistence. Celebrate small victories along the way to maintain morale, such as a successful petition drive or a policy concession. Simultaneously, remain vigilant against complacency by continually reassessing goals and tactics. The Fight for $15 campaign, for instance, began with localized strikes but expanded into a national movement by iteratively scaling its demands and tactics. By balancing short-term wins with long-term vision, collective action becomes a dynamic force capable of reshaping power structures and achieving enduring political goals.

Graceful Cancellation: How to Politely Reschedule or Cancel Appointments

You may want to see also

Ideology in Praxis: Applying political philosophies (e.g., Marxism, liberalism) to everyday struggles

Political praxis bridges the gap between abstract political theories and tangible actions, transforming ideologies like Marxism or liberalism into tools for addressing everyday struggles. Consider a tenant facing eviction in a gentrifying neighborhood. A Marxist lens might analyze this as a symptom of capitalist exploitation, where property owners prioritize profit over human dignity. Praxis here could involve organizing a rent strike, leveraging collective action to challenge the power imbalance. This isn’t merely theorizing about class struggle—it’s applying Marxist principles to disrupt systemic oppression in a specific, actionable way.

Liberalism, with its emphasis on individual rights and procedural fairness, offers a different praxis. For instance, a worker denied overtime pay could file a lawsuit, leveraging labor laws to assert their rights within the existing legal framework. This approach doesn’t seek to dismantle the system but to use its mechanisms to secure justice. The key is understanding liberalism’s focus on incremental reform and applying it strategically. For example, advocating for policy changes like raising the minimum wage combines liberal ideals with practical steps to improve livelihoods.

Applying ideology to praxis requires nuance. Take environmental activism: an eco-socialist might organize community gardens to challenge corporate agriculture, while a liberal environmentalist might lobby for carbon taxes. Both aim to address ecological crises but differ in scope and method. The former seeks systemic transformation, the latter policy adjustments. Neither is inherently superior; effectiveness depends on context. For instance, in a conservative community, liberal incrementalism might gain more traction than radical restructuring.

Caution is necessary when translating theory into action. Misapplication of ideology can lead to unintended consequences. For example, a rigid Marxist approach might alienate potential allies by dismissing incremental reforms, while unchecked liberal individualism can overlook structural inequalities. A balanced praxis integrates critique with pragmatism. Start by identifying the core issue (e.g., wage theft), then assess which ideological tools best address it. Combine Marxist analysis of power dynamics with liberal strategies like legal advocacy for a multi-pronged approach.

Ultimately, ideology in praxis is about adaptability. It’s not enough to believe in a philosophy—one must tailor it to the realities of specific struggles. A feminist fighting workplace harassment might use liberal legal channels while also organizing Marxist-inspired solidarity networks. The goal is to make ideologies serve the needs of the moment, not the other way around. Practical tips include mapping local power structures, building coalitions across ideological lines, and continuously evaluating the impact of actions. Praxis is iterative, not prescriptive—a living process of learning, acting, and refining.

Education's Dual Nature: Political Tool or Economic Engine?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Grassroots Organizing: Building local movements to address systemic issues and empower marginalized groups

Grassroots organizing is the lifeblood of political praxis, transforming abstract ideals into tangible change by anchoring movements in the lived experiences of communities. Unlike top-down approaches, it begins with listening—identifying systemic issues not through data alone but through the voices of those most affected. For instance, in the fight for environmental justice, grassroots organizers in low-income neighborhoods often start by mapping pollution hotspots alongside residents, linking health disparities to corporate negligence. This method doesn’t just diagnose problems; it builds trust and shared ownership, essential for sustained action.

To initiate a grassroots movement, start small but intentional. Assemble a core group of 5–10 committed individuals who reflect the diversity of the community. Avoid imposing agendas; instead, facilitate open dialogues where participants articulate their own needs and visions. For example, in a campaign for affordable housing, organizers might host community dinners where residents share stories of displacement, collectively identifying landlords or policies as common adversaries. Tools like participatory mapping or storytelling workshops can structure these conversations, ensuring marginalized voices dominate the narrative.

Scaling up requires strategic scaffolding. Once a shared goal emerges, break it into actionable steps—petitions, town hall disruptions, or direct actions like rent strikes. Leverage existing networks (churches, schools, local businesses) to amplify reach, but beware of co-optation. For instance, a youth-led climate justice group might partner with a local farmers’ market to distribute informational flyers, but only if the market aligns with their values. Digital tools like Signal for secure communication or Action Network for volunteer coordination can streamline efforts, but prioritize face-to-face relationships to maintain authenticity.

Empowerment is both the means and the end of grassroots organizing. Train participants in skills like public speaking, media engagement, or legal observation to build confidence and capacity. For marginalized groups, this skill-sharing disrupts power dynamics, turning victims into leaders. In a campaign against police brutality, for example, organizers might conduct "know your rights" workshops, equipping community members to document abuses and challenge authority. Celebrate small victories—a policy change, a media spotlight—to sustain momentum, but always tie them back to the broader vision of systemic transformation.

Finally, grassroots organizing demands resilience and adaptability. External pressures like funding scarcity, state repression, or internal conflicts are inevitable. Foster a culture of care, incorporating mental health check-ins or conflict resolution practices into meetings. Learn from failures: a failed protest might reveal a need for better coalition-building, while a successful one could expose new allies. By embedding flexibility into the movement’s DNA, organizers ensure it evolves with the community it serves, embodying the iterative spirit of political praxis.

Navigating the Political Arena: A Beginner's Guide to Joining Politics

You may want to see also

Critique of Praxis: Evaluating the effectiveness and limitations of political actions and strategies

Political praxis, the fusion of theory and practice in political action, is often celebrated for its transformative potential. Yet, its effectiveness hinges on rigorous critique. Without evaluation, praxis risks becoming dogma, disconnected from the realities it seeks to change. Consider the Civil Rights Movement: while nonviolent direct action achieved landmark legislation, its limitations surfaced in addressing systemic economic inequality. This example underscores the necessity of critique to refine strategies and ensure alignment with long-term goals.

To critique praxis effectively, begin by defining measurable objectives. What specific outcomes does the action aim to achieve? For instance, a campaign for universal healthcare might measure success by enrollment rates, cost reductions, and public health improvements. Next, assess the strategies employed. Are they inclusive, adaptable, and scalable? A grassroots movement relying solely on social media activism may exclude marginalized communities without internet access, revealing a critical limitation. Finally, evaluate unintended consequences. A policy advocating for stricter environmental regulations might inadvertently harm low-income workers in polluting industries, necessitating a more nuanced approach.

A persuasive critique of praxis demands accountability and transparency. Activists and policymakers must openly acknowledge failures and learn from them. The Occupy Wall Street movement, while galvanizing public discourse on economic inequality, lacked clear demands and organizational structure, limiting its tangible impact. By contrast, the Me Too movement’s focus on individual stories and systemic change has led to measurable shifts in workplace policies and public awareness. Transparency in both successes and shortcomings fosters trust and strengthens future efforts.

Comparatively, praxis in authoritarian regimes faces unique challenges. In such contexts, direct confrontation often leads to repression, while subtle, incremental strategies may lack visibility. Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement employed both mass protests and civil disobedience, achieving international attention but ultimately facing severe government crackdowns. This highlights the need for context-specific critique, balancing idealism with pragmatism. For activists in repressive environments, prioritizing survival and sustainability over immediate victories is a critical takeaway.

Instructively, critique should be iterative, not terminal. Treat it as a tool for improvement rather than a verdict of failure. Start by documenting actions and outcomes in detail. Use frameworks like SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) to systematically evaluate strategies. Engage diverse stakeholders for multifaceted perspectives. For example, a youth-led climate strike might involve educators, policymakers, and industry representatives in its critique process. Finally, incorporate feedback into revised strategies, ensuring continuous adaptation. A critique without actionable steps is mere observation; a critique with a plan is a catalyst for change.

Navigating Political Conversations: Tips for Respectful and Productive Discussions

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political praxis refers to the practical application of political theory or ideology in real-world actions and movements. It bridges the gap between ideas and concrete efforts to achieve social, economic, or political change.

Political theory focuses on developing ideas, concepts, and frameworks to understand political systems, while political praxis emphasizes the implementation of those ideas through activism, organizing, and direct action.

Key figures include Karl Marx, who emphasized the unity of theory and practice, and Paulo Freire, whose work on critical pedagogy highlights praxis as a tool for liberation and social transformation.

Examples include grassroots movements like civil rights campaigns, labor strikes, community organizing, and participatory democracy initiatives, where theoretical principles are applied to achieve tangible political or social goals.