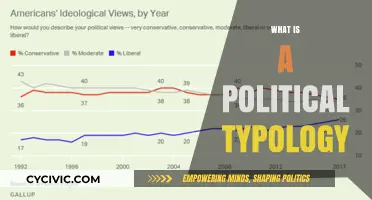

A political utopia is an idealized vision of a perfect society, often characterized by harmony, justice, and equality, where political systems function flawlessly to ensure the well-being of all citizens. Rooted in philosophical and literary traditions, it serves as a thought experiment to critique existing structures and inspire reform. While utopias are inherently unattainable, they offer a framework for imagining alternatives to societal flaws, such as inequality, oppression, or inefficiency. Political utopias vary widely, from Marxist classless societies to libertarian free-market paradises, reflecting diverse ideologies. Despite their impracticality, they play a crucial role in shaping political discourse, encouraging dialogue about what constitutes an ideal society and how to move closer to its principles.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Ideal Governance Structures: Exploring perfect systems of leadership and decision-making in a utopian society

- Economic Equality Models: Analyzing how resources are distributed fairly in a political utopia

- Social Harmony Mechanisms: Understanding methods to ensure unity and cooperation among citizens

- Environmental Sustainability: Integrating eco-friendly policies into utopian political frameworks

- Individual Freedoms vs. Collective Good: Balancing personal rights with societal welfare in utopia

Ideal Governance Structures: Exploring perfect systems of leadership and decision-making in a utopian society

A political utopia, by definition, envisions a society where governance is flawless, and leadership structures eliminate inefficiencies, corruption, and inequality. At its core, ideal governance in such a society must balance authority with accountability, ensuring decisions reflect the collective will while safeguarding individual freedoms. This delicate equilibrium demands a system that is both adaptive and principled, capable of evolving with societal needs without compromising its foundational ideals.

Consider a decentralized model where decision-making power is distributed across localized councils, each representing a specific community or interest group. These councils would operate under a framework of shared principles, ensuring alignment with the broader utopian vision. For instance, a council overseeing environmental policies might mandate that all decisions prioritize ecological sustainability, with metrics like carbon footprint reduction or biodiversity preservation serving as key performance indicators. This structure minimizes bureaucratic inertia while fostering direct citizen engagement, as individuals could participate in councils aligned with their expertise or passions.

However, decentralization alone is insufficient without mechanisms for coordination and conflict resolution. A utopian governance system might employ advanced consensus-building algorithms, leveraging artificial intelligence to synthesize diverse perspectives into coherent policies. For example, a proposed infrastructure project could be evaluated through a digital platform where citizens submit input, which the algorithm weighs based on relevance, feasibility, and alignment with utopian principles. This ensures decisions are both inclusive and efficient, reducing the risk of gridlock or domination by special interests.

Yet, even the most sophisticated systems require human oversight to maintain ethical integrity. A council of elders or sages, selected for their wisdom and impartiality, could serve as a final arbiter, reviewing decisions to ensure they uphold the society’s core values. This layer of moral guardianship would prevent technological or procedural biases from undermining justice. For instance, if an algorithm disproportionately favored urban development over rural preservation, the council could intervene to restore balance, guided by principles like equity and long-term sustainability.

Ultimately, the ideal governance structure in a utopian society is not a static blueprint but a dynamic framework that evolves with human progress. It must be rooted in transparency, participation, and adaptability, ensuring that leadership remains a tool for collective flourishing rather than control. By combining decentralized decision-making, technological innovation, and ethical oversight, such a system could approach the elusive ideal of perfect governance, where power serves the people, and decisions reflect the highest aspirations of humanity.

Understanding Political Powerlessness: Causes, Effects, and Paths to Empowerment

You may want to see also

Economic Equality Models: Analyzing how resources are distributed fairly in a political utopia

A political utopia, by definition, envisions a society free from conflict, inequality, and injustice. Central to this vision is economic equality, where resources are distributed in a manner that ensures every individual’s needs are met without fostering disparity. Achieving this requires models that go beyond theoretical fairness, embedding practical mechanisms for equitable distribution. Let’s explore how such models function, their challenges, and their potential real-world applications.

Consider the resource-based economy model, a system where goods and services are allocated based on availability rather than profit. In this framework, technology and automation play a pivotal role, eliminating scarcity by producing resources in abundance. For instance, renewable energy sources like solar and wind power could be harnessed to provide universal access to electricity, while vertical farming could address food shortages. The takeaway here is that technological innovation becomes the backbone of fairness, ensuring no one is left behind due to resource limitations. However, this model demands significant upfront investment in infrastructure and a societal shift away from consumerism, which may prove politically challenging.

Contrast this with the universal basic income (UBI) model, a more incremental approach to economic equality. UBI provides every citizen with a regular, unconditional sum of money, regardless of employment status. Pilot programs in countries like Finland and Kenya have shown promising results, reducing poverty and improving mental health. For example, a monthly stipend of $500 per adult could cover basic needs like food, housing, and healthcare, especially in regions with lower living costs. The strength of UBI lies in its simplicity and adaptability, but critics argue it could inflate costs of living if not paired with price controls. Implementing UBI requires careful calibration, such as adjusting the amount based on regional economic disparities and age categories (e.g., higher amounts for elderly citizens).

A third approach is the cooperative ownership model, where businesses and resources are collectively owned and managed by workers or communities. This decentralizes wealth accumulation and ensures profits are reinvested locally. For instance, employee-owned cooperatives in Spain, like Mondragon, have demonstrated sustained success by prioritizing fair wages and job security over shareholder returns. To replicate this, communities could start by converting small businesses into cooperatives, with government incentives such as tax breaks or low-interest loans. The challenge lies in scaling this model to larger industries, as it requires a cultural shift toward collective decision-making and shared responsibility.

While these models offer pathways to economic equality, their success hinges on addressing inherent trade-offs. For example, resource-based economies may stifle individual incentives, UBI could strain public finances, and cooperatives might struggle with efficiency. Yet, a hybrid approach—combining elements of each—could mitigate these risks. Imagine a society where automation ensures basic needs are met, UBI provides financial security, and cooperatives foster local economic resilience. Such a system would not only distribute resources fairly but also empower individuals to pursue meaningful work and community engagement.

In conclusion, economic equality in a political utopia is not a one-size-fits-all solution but a dynamic interplay of models tailored to societal needs. By leveraging technology, policy innovation, and community participation, we can move closer to a world where resources are not just distributed but shared equitably. The challenge lies not in the feasibility of these models but in the collective will to implement them.

Understanding Political Movements: Origins, Impact, and Societal Transformation

You may want to see also

Social Harmony Mechanisms: Understanding methods to ensure unity and cooperation among citizens

Political utopias often envision societies where conflict is minimized and cooperation is maximized. Achieving this requires deliberate mechanisms to foster social harmony. One such mechanism is the cultivation of shared values through education and cultural institutions. By embedding principles like empathy, mutual respect, and collective responsibility into curricula and public narratives, citizens are more likely to prioritize the common good over individual gain. For instance, Scandinavian countries emphasize *folkelig* (community spirit) in their education systems, which contributes to their high levels of social cohesion. This approach is not about indoctrination but about creating a framework where diverse perspectives align on fundamental human values.

Another effective method is the design of inclusive governance structures that ensure all voices are heard. Participatory budgeting, for example, allows citizens to directly influence how public funds are allocated, reducing feelings of alienation and fostering a sense of ownership in societal decisions. In Porto Alegre, Brazil, this practice has led to increased civic engagement and reduced inequality. However, such systems require safeguards against manipulation and must be paired with accessible education on civic processes to ensure meaningful participation across all demographics, including the elderly and less educated.

Conflict resolution frameworks also play a critical role in maintaining harmony. Restorative justice programs, which focus on reconciliation rather than punishment, have proven effective in reducing recidivism and rebuilding trust in communities. For instance, New Zealand’s Māori-inspired *Family Group Conferences* involve victims, offenders, and their families in resolving disputes, leading to higher satisfaction rates compared to traditional court systems. Implementing such programs requires training facilitators, allocating resources for mediation spaces, and shifting societal attitudes toward forgiveness and rehabilitation.

Finally, technological tools can be leveraged to enhance social harmony. Platforms that use AI to detect and mitigate online polarization, such as *Jigsaw’s Conversation AI*, can reduce the spread of divisive rhetoric. However, these tools must be ethically designed to avoid censorship or bias. Combining technology with community-based initiatives, like local dialogue forums, can create a balanced approach to fostering unity. For maximum impact, governments should invest in digital literacy programs to ensure citizens understand how algorithms shape their perceptions and interactions.

In conclusion, social harmony mechanisms are not one-size-fits-all solutions but require a combination of cultural, institutional, and technological strategies tailored to specific societal needs. By prioritizing shared values, inclusive governance, restorative justice, and ethical technology, political utopias can move closer to realizing their vision of unity and cooperation. The key lies in continuous adaptation and a commitment to equity, ensuring no one is left behind in the pursuit of harmony.

Where Do Political Analysts Work? Exploring Diverse Career Paths

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Sustainability: Integrating eco-friendly policies into utopian political frameworks

Political utopias, by definition, envision ideal societies where harmony, equality, and prosperity reign. Yet, without environmental sustainability, these visions crumble under the weight of ecological collapse. Integrating eco-friendly policies into utopian frameworks isn’t optional—it’s foundational. Consider this: a society cannot claim perfection if its rivers are poisoned, its air unbreathable, and its ecosystems collapsing. Sustainability must be the bedrock, not an afterthought.

To achieve this, utopian political frameworks must prioritize regenerative systems over extractive ones. For instance, a circular economy could replace linear models of production and consumption. Imagine cities where waste is virtually eliminated, resources are endlessly recycled, and energy is derived entirely from renewable sources like solar, wind, and geothermal. Policies mandating zero-waste manufacturing, carbon-neutral transportation, and biodiversity preservation would not only sustain the environment but also foster innovation and economic resilience.

However, eco-friendly policies alone aren’t enough. They must be embedded in a cultural ethos that values nature as sacred, not as a commodity. Education systems in this utopia would instill ecological literacy from childhood, teaching citizens to see themselves as stewards of the planet. Incentives for sustainable living—such as subsidies for green housing, tax breaks for eco-conscious businesses, and community-based conservation programs—would align individual behavior with collective goals. Without this cultural shift, even the most progressive policies risk becoming hollow.

A cautionary note: utopian visions often overlook the complexities of implementation. For example, transitioning to renewable energy requires massive infrastructure investments and could temporarily displace industries reliant on fossil fuels. To mitigate this, utopian frameworks must include just transition plans, ensuring workers in declining sectors are retrained and supported. Additionally, global cooperation is essential; environmental sustainability cannot be achieved in isolation. Utopian societies must lead by example, advocating for international agreements that prioritize planetary health over national interests.

In practice, integrating eco-friendly policies into utopian frameworks demands a delicate balance between ambition and pragmatism. Start with small-scale experiments—like community-owned renewable energy projects or urban farming initiatives—and scale them up. Use data-driven approaches to measure progress, such as tracking carbon footprints, water usage, and biodiversity indices. By combining visionary ideals with actionable steps, political utopias can become models for a sustainable future, proving that humanity can thrive without destroying the planet.

Understanding the Complex Dynamics of the Global Political Environment

You may want to see also

Individual Freedoms vs. Collective Good: Balancing personal rights with societal welfare in utopia

In a political utopia, the tension between individual freedoms and collective good is a defining challenge. At its core, this dilemma asks: How can a society maximize personal liberties without undermining the welfare of the community? Consider the example of healthcare. In a utopia, every individual might have the freedom to choose their treatment, but if those choices lead to widespread health risks—such as refusing vaccinations—the collective good suffers. This paradox illustrates the delicate balance required in an ideal society.

To navigate this balance, utopian models often employ a tiered approach to rights. Essential freedoms, such as speech and belief, remain absolute, while others, like resource consumption, are regulated to ensure sustainability. For instance, a utopia might allow unlimited creative expression but limit water usage to prevent scarcity. This system requires clear boundaries, enforced through transparent governance, to prevent overreach. The key is to prioritize freedoms that do not infringe on others’ well-being, a principle rooted in John Stuart Mill’s *harm principle*.

Persuasively, one could argue that true individual freedom thrives only when the collective good is secured. A society where basic needs like food, shelter, and safety are guaranteed allows individuals to pursue self-actualization without fear. For example, a utopia might implement a universal basic income (UBI) to ensure economic security, freeing individuals to innovate, create, or contribute to society in meaningful ways. This model shifts the focus from survival to flourishing, proving that collective welfare is not the enemy of personal liberty but its foundation.

Comparatively, historical and fictional utopias offer lessons. Plato’s *Republic* sacrifices individual desires for the state’s vision of justice, while More’s *Utopia* balances communal living with personal autonomy. In contrast, modern visions like Star Trek’s United Federation of Planets emphasize cooperation and shared prosperity without suppressing individuality. These examples highlight that the balance is not static but evolves with societal values, technology, and understanding of human needs.

Practically, achieving this balance requires continuous dialogue and adaptive policies. Utopian societies might use participatory decision-making, where citizens co-create laws that reflect both individual aspirations and collective priorities. For instance, a community could vote on environmental regulations, ensuring that personal freedoms align with ecological sustainability. Additionally, education plays a critical role, fostering a culture where individuals understand their rights and responsibilities. By embedding this awareness early—say, through civic education programs starting at age 10—societies can nurture a generation that values both self and community.

In conclusion, the utopian ideal of balancing individual freedoms and collective good is not a zero-sum game but a dynamic equilibrium. It demands thoughtful design, ethical governance, and a shared commitment to mutual flourishing. While no society has perfected this balance, the pursuit itself offers a roadmap for a more just and harmonious world.

Understanding Participatory Politics: Empowering Citizens in Democratic Engagement

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political utopia is an idealized society or system of government that is envisioned as perfect, often characterized by justice, equality, and harmony. It represents a theoretical framework for an optimal political order.

The term "utopia" was coined by Sir Thomas More in his 1516 book *Utopia*, which described an imaginary island with an ideal political and social system.

Most scholars argue that a political utopia is unattainable due to human imperfections, conflicting interests, and the complexity of societal dynamics. It serves more as a thought experiment or aspirational goal.

Common features include equality, absence of conflict, sustainable resource distribution, universal well-being, and a just governance system that prioritizes the common good.

While a political utopia envisions a perfect society, a dystopia depicts a society characterized by oppression, inequality, and suffering, often as a warning about the consequences of certain political or social choices.