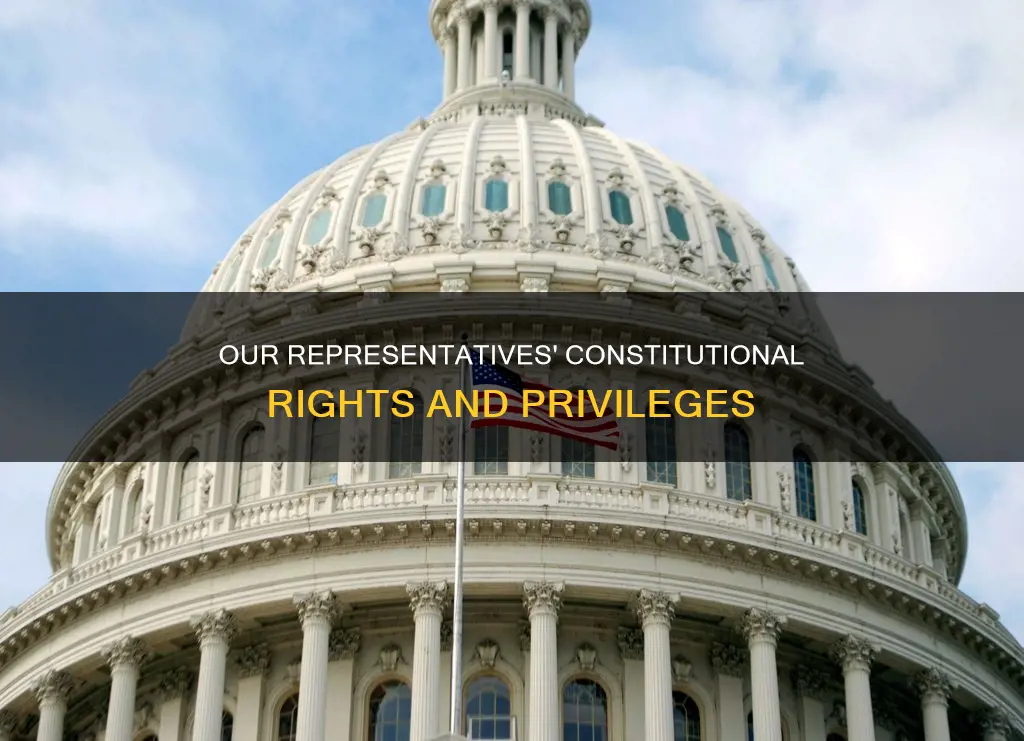

The Constitution of the United States grants a variety of powers to its representatives, including legislative, judicial, and executive powers. The Constitution establishes a system of checks and balances, with the legislative branch, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives, vested with the power to make laws. The Constitution also outlines the election process for representatives, their qualifications, and the rules of their proceedings. Additionally, it grants representatives the power to declare war, raise and support armies, and define and punish felonies. The President, as the head of the executive branch, is granted the power to grant reprieves and pardons for offenses, fill vacancies during Senate recess, and act as Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. The Constitution further grants representatives the authority to constitute inferior tribunals to the Supreme Court and outlines the judicial power's scope, encompassing cases arising under the Constitution, laws of the United States, and treaties.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Minimum age | 25 years |

| Citizenship | 7 years as a US citizen |

| Residence | Inhabitant of the state in which they are chosen |

| Election cycle | Every second year |

| Powers | Legislative |

| Commander-in-Chief | Of the Army and Navy of the United States |

| Powers | Grant reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States |

| Powers | Fill up vacancies during the recess of the Senate |

| Powers | Make or alter regulations regarding the times, places, and manner of holding elections |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Powers to declare war

The US Constitution grants Congress the power to declare war. Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution states that "Congress shall have the power…to declare war". This power is exclusively granted to Congress, and the President cannot declare war without Congress's approval.

The Constitution's framers were reluctant to give the President unilateral power to declare war, as they did not want to concentrate too much influence in the hands of a single person. They wanted declarations of war to be subject to careful debate in open forums among the public's representatives. Abraham Lincoln, a young first-term Congressman, wrote in 1848 during America's War with Mexico that:

> The provision of the Constitution giving the war-making powers to Congress, was dictated, as I understand it, by the following reasons, [...] Kings had always been involving and impoverishing their people in wars, pretending generally, if not always, that the good of the people was the object. This, our [Constitutional] Convention understood to be the most oppressive of all Kingly oppressions, and they resolved to so frame the Constitution that no one man should hold the power of bringing this oppression upon us.

While Congress has the sole power to declare war, the President is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces and has the power to direct the war. There is ongoing debate about the extent to which Congress's approval is required for the President to use military force. While most people agree that the President cannot declare war without Congress's approval, some argue that the President may initiate the use of force without a formal declaration of war.

Congress can also influence the President's ability to conduct military actions by providing or withholding funding and by passing legislation that cancels an existing state of war.

Compromises in the Constitution: A Foundation of Unity

You may want to see also

Powers to raise and support armies

Article I of the US Constitution outlines the design of the legislative branch of the US government, or Congress, and the powers it holds. One of these powers is the ability to "raise and support Armies".

This power was informed by the historical context of the English king, who had the authority to initiate wars and raise and maintain armies and navies. This ability was often used to the detriment of the English people, and the Framers of the Constitution were aware of this. As such, the power to raise and support armies was vested in Congress, rather than any one individual.

The Supreme Court has upheld the power of Congress to classify, conscript, raise, and regulate manpower for military service. This power has been deemed "beyond question". However, the Constitution does impose a limitation on this power: "no Appropriation of Money to that Use shall be for a longer Term than two Years". This was included to prevent the formation of standing armies, which had been a fear of the Framers.

The power of Congress to raise and support armies has been challenged on the grounds that it deprives the States of the right to a "well-regulated militia". However, the Supreme Court rejected this contention, stating that the powers of the States with respect to the militia were exercised in subordination to the power of the National Government to raise and support armies.

Constitutional Isomers of C4H8Cl2: Exploring Structural Diversity

You may want to see also

Powers to define and punish piracies and felonies

The Constitution grants Congress the power to define and punish piracies and felonies committed on the high seas, as well as offenses against the law of nations. This is known as the "Define and Punish Clause" and is outlined in Article I, which describes the legislative branch of the US government.

The power to define and punish piracies and felonies was a significant development in the US Constitution. During the drafting of the Constitution, there was debate over whether the terms "felonies" and "the law of nations" were sufficiently clear to be generally understood and applied. Initially, under the Articles of Confederation, Congress had the exclusive power to appoint courts for the trial of such crimes but lacked the express authority to define and punish them. The omission of a definition for these terms was viewed as a shortcoming that needed to be addressed in the Constitution.

The "Define and Punish Clause" grants Congress the authority to determine what constitutes piracy and felonies, as well as the corresponding punishments. This power extends beyond US territorial limits, allowing Congress to address crimes committed on the high seas. This was particularly important in the context of international law and maintaining peaceful relations with other nations.

The interpretation and application of the "Define and Punish Clause" have evolved over time. In the case of United States v. Smith (1820), the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional authority of Congress to define and punish piracy by adopting the definition established by international law. Additionally, in United States v. Arjona (1887), the Court validated Congress's power to punish offenses against the law of nations, even when the law itself did not explicitly reference the "Define and Punish Clause."

George Mason's Post-Constitution: A Legacy of Rights

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Powers to make rules concerning captures

Article I of the U.S. Constitution outlines the design of the legislative branch of the U.S. government, which is the Congress. It consists of a Senate and a House of Representatives, with legislative powers vested in this body.

The Constitution grants Congress the power to make rules concerning captures on land and water. This power is related to the authority to declare war, grant letters of marque and reprisal, and confiscate enemy property during wartime.

The power to make rules concerning captures has been interpreted and applied in various court cases throughout U.S. history. For example, in Brown v. United States (1814), Chief Justice Marshall clarified that Congress's declaration of war does not automatically result in the confiscation of enemy property within U.S. territory. However, Congress has the right to take further action to subject such property to confiscation.

During the Civil War, the Court addressed the Confiscation Act of 1861 and the Supplementary Act of 1863, which authorized the condemnation of vessels. The Court found that these acts did not override international law, specifically the law of prize, and that the government could proceed under international law rules, even if it deprived citizens of protective provisions under domestic statutes.

In the Spanish-American War, the Court held that the international law rule exempting unarmed fishing vessels from capture applied in the absence of any treaty provision or government action to the contrary. This demonstrated that international law is administered by U.S. courts unless modified by treaty or legislative/executive action.

Men: Evade the Draft, Understand Conscription Laws

You may want to see also

Powers to constitute tribunals

The US Constitution grants Congress the power to constitute tribunals inferior to the Supreme Court. This power is derived from Article I, which establishes the legislative branch of the US government, and Article IV, which grants Congress the authority to "make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States".

Article I tribunals, also known as legislative courts, are established by Congress to resolve disputes involving federal laws, including questions about the constitutionality of such laws. These tribunals are considered to have lesser power than the Executive Branch, and their decisions are subject to de novo review by supervising Article III courts, which retain the exclusive power to make and enforce final judgments. Congress can also create non-Article III tribunals to assist Article III courts with their workload, but only if the Article I tribunals are controlled by the Article III courts.

Article IV tribunals, also known as territorial courts, are established by Congress in US territories pursuant to its power under the Territorial Clause. These courts have jurisdiction over causes arising under both federal and local laws, but the application of constitutional guarantees in unincorporated territories is limited to "fundamental limitations in favor of personal rights" and "principles which are the basis of all free government which cannot be with impunity transcended".

The power to constitute tribunals allows Congress to create specialised forums for adjudicating disputes, thereby relieving the burden on regular courts. This power is limited to adjudication of public rights, such as disputes between citizens and the government, and Congress must respect the independence of the judiciary in the selection of tribunal members.

Meiji Constitution: Western Influence and Similarities

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A person must be at least 25 years old to be a Representative.

Representatives are chosen every second year by the people of the several states.

All legislative powers are vested in a Congress of the United States, which consists of a Senate and a House of Representatives.

The qualifications required to be an elector of Representatives are the same as those for electors of the most numerous branch of the state legislature.

The President is the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Navy, and Militia of the United States. They have the power to grant reprieves and pardons for offences against the United States, except in cases of impeachment. The President also has the power to fill up vacancies during the recess of the Senate by granting temporary commissions.

![Debates in the House of Representatives of the United States during the First Session of the Fourth Congress, Upon the Constitutional Powers of the House, with Respect to 1796 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)