Political districts are geographic areas established to represent specific populations in legislative bodies, such as Congress or state legislatures. These districts are designed to ensure equal representation by dividing a region into smaller, manageable units, each with roughly the same number of constituents. The process of creating these districts, known as redistricting, typically occurs after each decennial census to account for population changes. While intended to promote fair representation, the practice can be influenced by political interests, leading to issues like gerrymandering, where district boundaries are manipulated to favor a particular party or group. Understanding political districts is crucial for grasping how electoral systems function and how they can impact political outcomes.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Geographic areas designated for political representation and governance. |

| Purpose | To ensure fair representation in legislative bodies and electoral systems. |

| Types | Electoral districts, congressional districts, parliamentary constituencies, wards, precincts. |

| Population | Ideally equal or proportional across districts to ensure equal representation (e.g., "one person, one vote"). |

| Boundaries | Determined by legislative bodies, independent commissions, or courts; often subject to redistricting. |

| Redistricting | Process of redrawing district boundaries, typically after a census, to reflect population changes. |

| Gerrymandering | Practice of manipulating district boundaries for political advantage, often criticized as unfair. |

| Representation | Each district elects one or more representatives to a legislative body (e.g., Congress, Parliament). |

| Legal Basis | Established by national or state laws, constitutions, or electoral regulations. |

| Size | Varies by country and system; e.g., U.S. congressional districts average ~760,000 people (post-2020 census). |

| Function | Facilitates localized governance, constituent engagement, and resource allocation. |

| Examples | U.S. House districts, UK parliamentary constituencies, Indian Lok Sabha constituencies. |

| Criticisms | Unequal representation due to malapportionment, gerrymandering, and demographic disparities. |

| Global Variations | Structures and names differ; e.g., "ridings" in Canada, "circonscriptions" in France. |

Explore related products

$11.95

What You'll Learn

- Gerrymandering: Manipulating district boundaries to favor a political party or group

- Apportionment: Allocating legislative seats based on population data

- Redistricting: Periodic redrawing of district lines after census updates

- Single-Member Districts: Districts electing one representative per geographic area

- At-Large Districts: Entire regions electing representatives without geographic subdivision

Gerrymandering: Manipulating district boundaries to favor a political party or group

Political districts are geographic areas designed to represent communities in legislative bodies, but their boundaries aren’t always drawn with fairness in mind. Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating these boundaries to favor a specific political party or group, distorts democratic representation. By strategically packing opponents into a few districts or cracking them across many, those in power can secure disproportionate control, even when their popular support is thin. This tactic undermines the principle of "one person, one vote," turning elections into predetermined outcomes rather than genuine contests of public will.

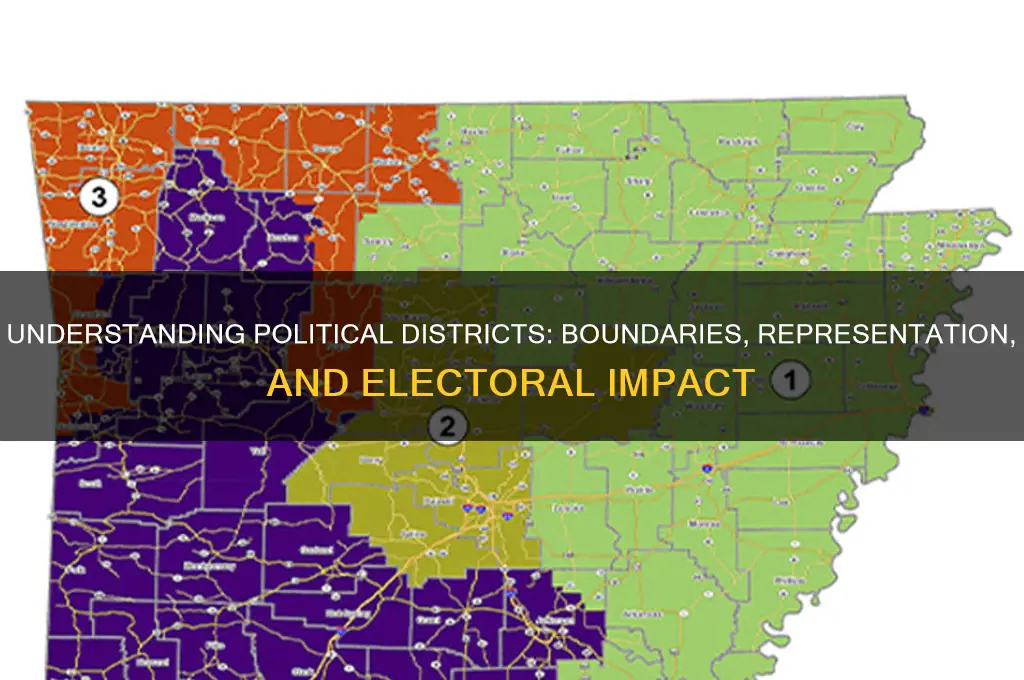

Consider the 2012 U.S. House elections in Pennsylvania. Despite Democrats winning 50.5% of the statewide vote, they secured only 5 of the state’s 18 congressional seats. How? Republican-controlled redistricting packed Democratic voters into densely blue urban districts while spreading the rest thinly across Republican-leaning areas. This isn’t an isolated case; similar patterns emerge in states like North Carolina and Ohio, where courts have repeatedly struck down maps as unconstitutional. The result? A system where politicians choose their voters, not the other way around.

To spot gerrymandering, look for districts with bizarre shapes—snaking lines, jagged edges, or appendages reaching across counties. These aren’t accidents of geography but deliberate designs to dilute opposition votes. Tools like spatial analysis software and voter turnout data can reveal discrepancies between population distribution and district boundaries. For instance, a district with a 70%+ majority for one party often signals packing, while a district splitting a cohesive community (like a city) across multiple lines suggests cracking.

Combating gerrymandering requires both legal and technological solutions. Independent redistricting commissions, as used in California and Arizona, remove partisan influence from the process. Algorithms can generate maps prioritizing compactness and community integrity over political advantage. However, even these aren’t foolproof; commissions can be stacked with partisan appointees, and algorithms reflect the biases of their creators. Public vigilance, transparency in map-drawing, and robust legal challenges remain essential to restoring fairness.

Ultimately, gerrymandering isn’t just a technical issue—it’s a threat to democracy itself. When district lines are weaponized, elections lose their legitimacy, and citizens lose faith in the system. The fight against gerrymandering isn’t about favoring one party over another; it’s about ensuring that every vote counts equally. Until we address this manipulation, the promise of representative government will remain unfulfilled.

Mastering Polite Persistence: Effective Strategies for Professional Follow-Ups

You may want to see also

Apportionment: Allocating legislative seats based on population data

Apportionment is the process of distributing legislative seats among political districts based on population data, ensuring that representation reflects demographic changes. This system aims to achieve fairness by aligning the number of representatives with the number of constituents, but it’s far from simple. The U.S. Census, conducted every 10 years, provides the population counts that drive this process, yet even this foundational step is fraught with challenges like undercounting marginalized communities. Without accurate data, apportionment can perpetuate inequalities, making the integrity of the census a critical yet often overlooked issue.

Consider the method of apportionment itself, which varies by country and level of government. The United States uses the Method of Equal Proportions, a mathematical formula designed to minimize the percentage difference in population between the largest and smallest congressional districts. For instance, after the 2020 Census, states like Texas gained seats due to population growth, while others like California lost them for the first time in history. This method, while mathematically sound, can still produce paradoxes, such as the Alabama Paradox, where increasing the total number of seats can reduce a state’s allocation. Such quirks highlight the tension between mathematical precision and practical fairness.

Apportionment isn’t just a numbers game—it’s a political battleground. The process is often weaponized through gerrymandering, where district lines are manipulated to favor one party over another. For example, in North Carolina, courts struck down maps in 2019 that were drawn to disproportionately favor Republicans, despite the state’s relatively even split between Democratic and Republican voters. To combat this, some states, like California, have adopted independent redistricting commissions, which remove partisan influence from the process. These reforms underscore the importance of transparency and accountability in ensuring that apportionment serves voters, not politicians.

Finally, apportionment has global implications, though methods differ widely. In the European Parliament, for instance, seats are allocated using degressive proportionality, where smaller countries receive more seats per capita than larger ones to ensure their voices aren’t drowned out. This contrasts sharply with the U.S. system, which prioritizes equal representation within states. Such variations reflect differing values about fairness and equity, reminding us that apportionment is as much a philosophical question as a technical one. Understanding these systems can empower citizens to advocate for reforms that better align representation with democratic ideals.

Understanding Political Will: Definition, Importance, and Impact on Governance

You may want to see also

Redistricting: Periodic redrawing of district lines after census updates

Every ten years, the U.S. Census Bureau conducts a population count, and the results trigger a critical democratic process: redistricting. This is the redrawing of political district lines to reflect shifts in population, ensuring each district represents roughly the same number of people. It’s a mathematical exercise with profound political implications, as it directly impacts the balance of power in legislative bodies. For instance, a state gaining population might earn an additional seat in the House of Representatives, necessitating a complete reconfiguration of its districts. Conversely, a state losing population may need to consolidate districts, potentially pitting incumbents against each other in newly drawn territories.

The mechanics of redistricting are deceptively simple but fraught with complexity. First, census data is released, detailing population changes at the county, city, and neighborhood levels. State legislatures or independent commissions then use this data to redraw district maps, aiming for equal population distribution. However, the process is rarely neutral. Partisanship often creeps in, with the party in power seeking to maximize its electoral advantage through tactics like gerrymandering—manipulating district boundaries to favor one group over another. For example, “cracking” dilutes the influence of opposition voters by spreading them across multiple districts, while “packing” concentrates them into a single district to limit their broader impact.

To mitigate these risks, some states have adopted reforms. Independent redistricting commissions, composed of non-partisan citizens, are increasingly popular. California’s Citizens Redistricting Commission, established in 2010, is a model example. It requires public input, transparency, and adherence to criteria like maintaining communities of interest and geographic continuity. Similarly, states like Arizona and Michigan have shifted redistricting authority away from legislatures to reduce partisan manipulation. These reforms aim to restore fairness, though challenges remain, as seen in legal battles over alleged gerrymandering in states like North Carolina and Wisconsin.

Redistricting’s impact extends beyond state legislatures to local governments and even school boards. At the federal level, it reshapes the House of Representatives and, by extension, the Electoral College. For voters, the consequences are tangible: district lines determine which candidates appear on ballots and which issues dominate campaigns. A poorly drawn district can silence minority voices, while a well-drawn one can amplify them. For instance, the 2020 redistricting cycle saw significant changes in states like Texas and New York, where shifting demographics led to the creation of new majority-minority districts, potentially altering the political landscape for decades.

Practical tips for citizens include staying informed about redistricting timelines and participating in public hearings. Tools like online mapping platforms allow individuals to propose their own district configurations, fostering transparency and accountability. Advocacy groups also play a crucial role, monitoring the process and challenging unfair maps in court. Ultimately, redistricting is more than a bureaucratic exercise—it’s a cornerstone of representative democracy, ensuring that political power reflects the will of the people. As the 2030 census approaches, the stakes will only grow, making informed engagement essential.

Muhammad's Political Leadership: Myth or Historical Reality?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Single-Member Districts: Districts electing one representative per geographic area

Single-member districts, the cornerstone of many electoral systems, are geographic areas designed to elect one representative to a legislative body. This structure contrasts with multi-member districts, where multiple representatives are elected from a single area. The simplicity of single-member districts lies in their directness: one district, one representative, one vote per voter. This system is widely used in countries like the United States (for the House of Representatives), the United Kingdom, and Canada, where it is known as the "first-past-the-post" system. Its appeal stems from its clarity and ease of implementation, but it also raises questions about representation and fairness.

Consider the mechanics of single-member districts. Each district is drawn to contain roughly the same number of voters, ensuring equal representation in theory. However, the process of redistricting—redrawing district boundaries—can lead to gerrymandering, where boundaries are manipulated to favor a particular party or group. For instance, in the U.S., state legislatures often control redistricting, leading to accusations of partisan bias. To mitigate this, some states use independent commissions to draw district lines. Practical tip: Voters can advocate for transparent redistricting processes by engaging with local government and supporting nonpartisan reform efforts.

The impact of single-member districts on political outcomes is significant. Because only one candidate wins per district, this system tends to favor a two-party structure, as smaller parties struggle to gain representation. For example, in the U.K., the Conservative and Labour parties dominate, while smaller parties like the Liberal Democrats secure fewer seats despite having substantial vote shares. This winner-takes-all dynamic can marginalize minority viewpoints, but it also promotes stability by encouraging coalition-building within parties. Analytical takeaway: While single-member districts simplify elections, they may underrepresent diverse political perspectives.

A comparative lens reveals the trade-offs of single-member districts. In contrast to proportional representation systems, where parties gain seats based on their share of the national vote, single-member districts prioritize local representation. For instance, a rural district in Canada may elect a representative focused on agricultural issues, while an urban district prioritizes public transit. This localized focus can lead to more responsive governance but may neglect national priorities. Caution: Overemphasis on local issues can fragment policy-making, making it harder to address broad societal challenges.

Finally, the design of single-member districts influences voter behavior and campaign strategies. Candidates must appeal to a majority of voters within their district, often tailoring their messages to local concerns. This can lead to hyper-local campaigns, where national issues take a backseat. For voters, the system is straightforward: choose one candidate to represent your area. However, this simplicity can also lead to strategic voting, where voters support a candidate not out of preference but to block another. Practical tip: Voters should research candidates’ positions on both local and national issues to make informed decisions. Conclusion: Single-member districts offer clarity and localized representation but require vigilance to ensure fairness and inclusivity.

Understanding the Role of a Political Commissar in Military and Politics

You may want to see also

At-Large Districts: Entire regions electing representatives without geographic subdivision

At-large districts represent a distinct approach to political representation, where an entire region elects representatives without dividing the area into smaller geographic subdivisions. Unlike single-member or multi-member districts, which carve regions into specific zones, at-large systems allow all voters within a jurisdiction—be it a city, county, or state—to vote for every representative seat. This method is commonly seen in municipal elections, where city councils or school boards are elected by the entire population rather than by wards or precincts. For example, in cities like Phoenix, Arizona, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, council members are elected at-large, meaning every voter participates in selecting each representative.

The mechanics of at-large districts are straightforward: candidates run for a set number of seats, and the top vote-getters win, regardless of their geographic origin within the region. This system contrasts sharply with district-based elections, where candidates must appeal to a specific locality. At-large elections can simplify the voting process for citizens, as they focus on fewer races and broader issues. However, this simplicity comes with trade-offs. Without geographic boundaries, at-large systems risk diluting the representation of minority groups or localized communities, as candidates may prioritize appealing to the majority demographic or the most populous areas.

One of the most debated aspects of at-large districts is their impact on fairness and diversity in representation. Critics argue that this system often disadvantages minority voters, as their collective voting power is spread across the entire electorate rather than concentrated in specific districts. For instance, in a city with a significant racial minority, at-large elections may result in no representatives from that group being elected if their votes are outnumbered by the majority. This issue has led to legal challenges under the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits practices that dilute minority voting strength. Cities like Birmingham, Alabama, and Galveston, Texas, have transitioned from at-large to district-based systems following such challenges.

Despite these criticisms, at-large districts offer certain advantages. They encourage candidates to adopt region-wide perspectives, fostering policies that benefit the entire community rather than specific neighborhoods. This can be particularly valuable in small towns or homogeneous regions where local divisions are less pronounced. Additionally, at-large systems can reduce the influence of gerrymandering, as there are no district lines to manipulate. For jurisdictions considering this approach, it’s essential to weigh the benefits of unity and simplicity against the risks of underrepresented subgroups. Practical steps include conducting demographic analyses to predict representation outcomes and engaging in public dialogue to address concerns.

In conclusion, at-large districts provide a unique framework for political representation, emphasizing broad-based elections over localized divisions. While they offer simplicity and a unified vision, they also pose challenges to equitable representation. Jurisdictions adopting this system must carefully assess their demographic makeup and implement safeguards to ensure all voices are heard. By understanding these dynamics, communities can make informed decisions about whether at-large elections align with their democratic goals.

Understanding Political Revolution: Mechanisms, Drivers, and Societal Transformation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political districts are geographic areas defined for the purpose of electing representatives to government bodies, such as legislative assemblies or councils.

Political districts are typically created through a process called redistricting, which involves drawing boundaries based on population data, legal requirements, and sometimes political considerations.

Political districts ensure fair representation by dividing populations into manageable areas, allowing voters to elect officials who reflect their local interests and needs.

Gerrymandering is the practice of manipulating district boundaries to favor a particular political party or group, often resulting in unfairly drawn districts that dilute the voting power of certain communities.

Political districts are typically redrawn every 10 years following the U.S. Census (or equivalent in other countries) to account for population changes and ensure equal representation.

![2 Pack - World Map Poster & USA Map Chart [Tan/Color] (LAMINATED, 18” x 29”)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/A1aLNThapcS._AC_UL320_.jpg)