Political dynamics refer to the complex interactions, relationships, and power structures that shape decision-making processes within governments, organizations, and societies. These dynamics encompass the interplay between various actors, including political parties, interest groups, leaders, and citizens, as they navigate competing interests, ideologies, and resources. Influenced by historical contexts, cultural norms, and socio-economic factors, political dynamics determine how policies are formed, conflicts are resolved, and power is distributed. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for analyzing how political systems function, evolve, and respond to challenges, as well as for predicting outcomes in both domestic and international arenas.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Power Struggles | Competition for control, influence, and resources among individuals/groups |

| Ideological Conflicts | Clashes between differing political beliefs, values, and worldviews |

| Institutional Structures | Formal rules, norms, and organizations shaping political behavior |

| Interest Groups | Organizations advocating for specific policies or agendas |

| Public Opinion | Collective attitudes and beliefs influencing political decisions |

| Leadership Styles | Varied approaches to governance, e.g., authoritarian vs. democratic |

| Global Influences | International relations, geopolitics, and external pressures |

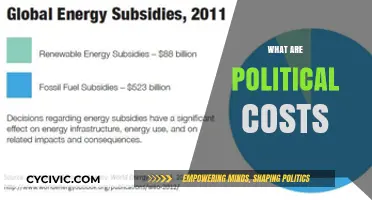

| Economic Factors | Resource distribution, wealth inequality, and economic policies |

| Social Movements | Grassroots efforts driving political change or resistance |

| Media Influence | Role of news outlets and social media in shaping narratives |

| Electoral Processes | Mechanisms for selecting leaders and making political decisions |

| Conflict Resolution | Methods for addressing disputes, e.g., negotiation, compromise |

| Cultural Norms | Societal values and traditions impacting political behavior |

| Technological Impact | Role of technology in political communication and mobilization |

| Crisis Management | Responses to emergencies, e.g., pandemics, wars, or economic crises |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Power Structures: Examines how authority is distributed and exercised within political systems

- Interest Groups: Analyzes the role of organizations in shaping policy and public opinion

- Electoral Systems: Explores mechanisms for voting, representation, and their impact on governance

- Conflict Resolution: Studies methods for managing disputes and maintaining political stability

- Global Influence: Investigates how international actors affect domestic and foreign policies

Power Structures: Examines how authority is distributed and exercised within political systems

Power structures are the backbone of any political system, defining who holds authority, how decisions are made, and who benefits. At their core, they reveal the invisible lines of control that shape governance, policy, and societal outcomes. For instance, in a presidential system like the United States, power is formally divided among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, yet informal networks—such as lobbying groups or party elites—often wield significant influence behind the scenes. Understanding these structures requires mapping both formal institutions and the informal mechanisms that can either reinforce or subvert them.

To analyze power structures effectively, begin by identifying the key actors within a political system. These may include government officials, political parties, corporations, or civil society organizations. Next, examine the rules and norms that govern their interactions, such as constitutional provisions, electoral laws, or cultural expectations. For example, in a parliamentary system like the United Kingdom, the Prime Minister’s authority derives from their party’s majority in Parliament, but their power can be constrained by internal party dynamics or public opinion. By dissecting these relationships, you can uncover how authority is distributed and exercised in practice.

A critical aspect of power structures is their adaptability—or lack thereof—to changing circumstances. In authoritarian regimes, power is often concentrated in the hands of a single leader or party, with limited mechanisms for accountability. However, even in such systems, power is not absolute; it relies on the cooperation of bureaucrats, security forces, and economic elites. For instance, the longevity of Vladimir Putin’s rule in Russia depends not only on his personal authority but also on the loyalty of oligarchs and regional governors. Conversely, in democratic systems, power is more diffuse, but this can lead to gridlock or inefficiency, as seen in the U.S. Congress during periods of partisan polarization.

To navigate power structures in practice, consider these actionable steps: first, identify the formal and informal channels through which decisions are made. Second, assess the incentives and constraints facing key actors, such as electoral pressures, ideological commitments, or personal ambitions. Third, recognize the role of external factors, like economic crises or international relations, in reshaping power dynamics. For example, the 2008 financial crisis led to a shift in power from financial elites to regulatory bodies in many Western countries. By adopting this analytical framework, you can better predict how power structures will evolve and how to influence them strategically.

Ultimately, power structures are not static; they are shaped by historical context, cultural norms, and the actions of individuals and groups. While formal institutions provide a framework for governance, the real exercise of authority often occurs in the gray areas between rules and reality. By studying these dynamics, you gain insight into why certain policies succeed or fail, why some voices are amplified while others are silenced, and how change can be achieved within existing systems. Whether you are a policymaker, activist, or citizen, understanding power structures is essential for navigating—and potentially transforming—the political landscape.

Are Political Commentary Opinion Pieces Shaping Public Perception?

You may want to see also

Interest Groups: Analyzes the role of organizations in shaping policy and public opinion

Interest groups, often operating behind the scenes, wield significant influence in the political arena, acting as catalysts for policy change and public opinion shifts. These organizations, driven by specific agendas, employ various strategies to shape the political landscape. Consider the National Rifle Association (NRA) in the United States, a powerful interest group advocating for gun rights. Through lobbying, grassroots mobilization, and strategic donations, the NRA has successfully influenced legislation, ensuring that gun control measures face substantial hurdles. This example illustrates how interest groups can become pivotal players in policy formation, often determining the trajectory of political debates.

The Art of Lobbying and Advocacy:

Interest groups excel in the art of persuasion, employing lobbyists to navigate the intricate corridors of power. These lobbyists engage with policymakers, providing research, data, and arguments to support their cause. For instance, environmental organizations might lobby for stricter emissions regulations, presenting scientific evidence of climate change impacts. This direct engagement with decision-makers allows interest groups to shape policies from within the political system. Moreover, they often draft model legislation, offering ready-made solutions to lawmakers, thereby streamlining the policy-making process in their favor.

Mobilizing the Masses: Grassroots Power

Beyond the halls of government, interest groups harness the power of public opinion through grassroots campaigns. They organize rallies, petitions, and social media movements to galvanize supporters and sway public sentiment. The #MeToo movement, for instance, gained momentum through grassroots activism, leading to increased public awareness and policy changes regarding sexual harassment. Interest groups understand that public opinion can be a powerful tool, often translating into political pressure on elected officials. By mobilizing citizens, these organizations create a groundswell of support (or opposition) that policymakers cannot ignore.

Media and Messaging: Shaping Public Narrative

Mastery of media and messaging is another critical aspect of interest group strategies. They employ public relations experts to craft narratives that resonate with the public and attract media attention. For instance, a group advocating for healthcare reform might use personal stories of patients struggling with high medical costs to humanize their cause. Through op-eds, press conferences, and social media campaigns, interest groups can set the agenda for public discourse, ensuring their issues gain prominence. This media savvy approach allows them to influence not just policymakers but also the general public's perception of various issues.

In the complex world of political dynamics, interest groups emerge as key players, capable of steering policy and public opinion in their desired direction. Their influence is multifaceted, combining lobbying, grassroots mobilization, and media strategies to achieve their goals. Understanding these tactics is essential for anyone seeking to navigate or influence the political landscape, as it reveals the intricate dance between organized interests and the democratic process. By analyzing these methods, we can better comprehend how policies are shaped and public discourse is molded, ultimately leading to more informed civic engagement.

Was Connor Betts Politically Motivated? Unraveling the Dayton Shooter's Intentions

You may want to see also

Electoral Systems: Explores mechanisms for voting, representation, and their impact on governance

Electoral systems are the backbone of democratic governance, shaping how votes translate into political power. Consider the difference between first-past-the-post (FPTP) and proportional representation (PR) systems. In FPTP, used in countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, the candidate with the most votes in a district wins, often leading to majority governments even with less than 50% of the popular vote. PR systems, such as those in Germany and New Zealand, allocate parliamentary seats based on parties’ vote shares, fostering coalition governments and greater representation of smaller parties. This fundamental design choice influences not just election outcomes but also the stability and inclusivity of governance.

To understand the impact of electoral systems, examine their effects on voter behavior and party strategies. In FPTP systems, voters often engage in strategic voting, supporting a candidate not necessarily their first choice but one with a better chance of defeating an undesirable opponent. This phenomenon, known as "Duverger’s Law," can marginalize smaller parties and polarize politics. Conversely, PR systems encourage parties to appeal to niche demographics, leading to a more diverse political landscape. For instance, Germany’s mixed-member proportional system combines direct constituency representation with party-list seats, balancing local accountability with proportionality. Such mechanisms highlight how electoral rules shape not just who wins but also how campaigns are waged and issues prioritized.

Implementing or reforming an electoral system requires careful consideration of context and goals. For instance, transitioning from FPTP to PR can increase representation but may also lead to fragmented legislatures and frequent coalition negotiations. Countries like Italy have grappled with this trade-off, experimenting with mixed systems to balance stability and proportionality. Practical steps for reform include conducting public consultations, analyzing electoral data, and piloting new systems in local elections. Caution is advised when adopting complex systems, as voter confusion can undermine legitimacy. For example, Australia’s ranked-choice voting system, while ensuring majority winners, demands voter education to navigate preference allocation effectively.

The choice of electoral system also has long-term implications for governance and societal cohesion. In deeply divided societies, PR can provide a platform for minority voices, reducing grievances and fostering inclusivity. However, without strong institutions, it may exacerbate fragmentation and gridlock. Conversely, FPTP can deliver decisive outcomes but risks alienating significant voter blocs. South Africa’s post-apartheid adoption of PR exemplifies how electoral design can support democratic consolidation, while India’s FPTP system, inherited from colonial rule, continues to shape its majoritarian politics. These examples underscore the need to align electoral mechanisms with a nation’s political culture and developmental stage.

Ultimately, electoral systems are not neutral tools but powerful instruments that structure political dynamics. Their design determines whether power is concentrated or dispersed, whether diversity is celebrated or suppressed, and whether governance is stable or volatile. Policymakers and citizens alike must critically evaluate these mechanisms, recognizing that the rules of the game profoundly influence the outcomes. By studying comparative cases and engaging in informed debate, societies can craft electoral systems that reflect their values and aspirations, ensuring democracy serves its intended purpose: to represent the will of the people.

Unveiling Political Subsystems: Funding Sources and Financial Mechanisms Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Conflict Resolution: Studies methods for managing disputes and maintaining political stability

Political conflicts, whether between nations, parties, or interest groups, are inherent to the human condition. Yet, their escalation can destabilize societies, disrupt economies, and erode trust. Conflict resolution, therefore, emerges as a critical discipline within political dynamics, offering structured methods to de-escalate disputes and preserve stability. At its core, it involves understanding the root causes of conflict, identifying stakeholders’ interests, and crafting mutually acceptable solutions. Without effective resolution mechanisms, even minor disagreements can metastasize into crises, making this field indispensable for governance and diplomacy.

One widely studied method in conflict resolution is negotiation, a process where parties engage in dialogue to reach a compromise. For instance, the Camp David Accords of 1978 demonstrate how negotiation can transform adversarial relationships into peace agreements. Key to successful negotiation is the principle of mutual gains, where both sides perceive value in the outcome. Practitioners often employ techniques like active listening, reframing issues, and separating people from problems. However, negotiation requires goodwill and a shared desire for resolution, which may not always be present in deeply polarized environments.

When negotiation falters, mediation steps in as a structured alternative. Here, a neutral third party facilitates communication, helping disputants find common ground. The Oslo Accords of 1993, mediated by Norway, exemplify how external mediators can bridge divides in intractable conflicts. Mediation is particularly effective when emotions run high, as mediators can diffuse tension and refocus discussions on tangible issues. Yet, its success hinges on the mediator’s impartiality and the parties’ willingness to cede some control over the process.

For conflicts rooted in systemic inequalities or historical grievances, transformative approaches offer a deeper solution. These methods aim not just to resolve the immediate dispute but to address underlying power imbalances and foster long-term reconciliation. South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission post-apartheid is a landmark example, where acknowledging past injustices paved the way for societal healing. While transformative approaches are resource-intensive and time-consuming, they hold the potential to break cycles of violence and build sustainable peace.

Despite these tools, conflict resolution is not without challenges. Power asymmetries often skew outcomes in favor of dominant parties, undermining fairness. Cultural barriers can hinder communication, as norms and values differ across groups. Moreover, spoilers—individuals or factions opposed to peace—can derail even the most carefully crafted agreements. Practitioners must navigate these complexities with sensitivity, employing strategies like power-balancing mechanisms, cultural competency training, and inclusive stakeholder engagement.

In conclusion, conflict resolution is both an art and a science, requiring tactical skill and strategic vision. By mastering negotiation, mediation, and transformative methods, political actors can manage disputes effectively and maintain stability. However, success demands adaptability, empathy, and a commitment to equity. As global tensions rise, the study and application of these methods become not just academic exercises but urgent imperatives for a fractured world.

Understanding JQ: Its Role and Impact in Political Discourse

You may want to see also

Global Influence: Investigates how international actors affect domestic and foreign policies

International actors—ranging from sovereign states and multinational corporations to NGOs and cyber collectives—exert measurable influence on domestic policies worldwide. Consider the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which, despite being a regional law, forces companies globally to adapt their data handling practices or face steep fines (up to 4% of annual turnover). This example illustrates how external regulatory frameworks can reshape internal policies, often bypassing traditional legislative processes. Similarly, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has compelled participating nations to align infrastructure projects with Chinese strategic interests, effectively embedding foreign priorities into local development agendas. Such dynamics highlight how international actors can act as de facto policymakers, leveraging economic, legal, or strategic tools to shape domestic outcomes.

To analyze this phenomenon systematically, examine the mechanisms through which global influence operates. Economic interdependence, as seen in the U.S.-China trade war, can force nations to recalibrate tariffs, subsidies, or labor laws to avoid market exclusion. Cultural diffusion, exemplified by the global spread of K-pop or American entertainment, subtly shifts societal norms and political attitudes. Meanwhile, transnational advocacy networks—like Amnesty International or the World Economic Forum—pressure governments to adopt human rights standards or climate policies. Each mechanism varies in immediacy and visibility, but all converge to create a hybrid policy space where domestic and international interests intertwine. Mapping these pathways reveals how global actors exploit or create vulnerabilities within national systems.

A comparative lens underscores the asymmetry in global influence. While G7 nations often dictate international norms—such as the OECD’s global tax agreement—smaller states like Singapore or Qatar wield disproportionate power through strategic positioning (e.g., financial hubs or energy reserves). Conversely, fragile states may become battlegrounds for competing foreign agendas, as seen in Syria’s proxy conflicts. This disparity suggests that influence is not merely a function of size or wealth but of strategic leverage. For instance, Taiwan’s semiconductor dominance grants it outsized geopolitical relevance, illustrating how niche capabilities can translate into global policy impact.

To mitigate unintended consequences of external influence, policymakers must adopt a three-step framework: audit, adapt, and align. First, audit existing policies for foreign dependencies—whether in supply chains, technology, or funding. Second, adapt by diversifying partnerships or building domestic resilience, as India did with its "Atmanirbhar Bharat" (self-reliant India) initiative. Third, align international engagement with long-term national interests, as Canada does by balancing U.S. trade reliance with Pacific Alliance diversification. Caution is warranted against over-reactionary protectionism, which can stifle innovation, or naive globalism, which risks sovereignty erosion. The goal is not to eliminate external influence but to manage it strategically.

Ultimately, global influence is neither inherently benevolent nor malign—its impact depends on context and response. Nations that proactively engage with international actors, as Germany does in EU negotiations, can shape outcomes in their favor. Those that react passively, like some African states in resource extraction deals, often cede control. The takeaway is clear: understanding and navigating global influence is not optional but essential for policy sovereignty in an interconnected world. Practical steps include investing in intelligence capabilities to monitor foreign interventions, fostering public awareness of global pressures, and embedding international relations expertise within domestic policy teams. In this dynamic, influence becomes a tool to wield, not a force to endure.

Understanding Politically Exposed Persons: Risks, Regulations, and Compliance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political dynamics refer to the interactions, relationships, and power structures that shape political processes and outcomes. They encompass how individuals, groups, institutions, and ideologies influence decision-making, policy formation, and governance.

Political dynamics influence policy-making by determining which issues gain attention, how stakeholders negotiate, and the distribution of resources. Factors like party politics, public opinion, and interest groups play a crucial role in shaping the direction and implementation of policies.

Yes, political dynamics are fluid and can evolve due to shifts in public sentiment, economic conditions, technological advancements, or leadership changes. Events like elections, crises, or social movements often accelerate these changes.

![Republicanism: A Theory of Freedom and Government [Oxford Political Theory Series]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71osdyMbfjL._AC_UY218_.jpg)