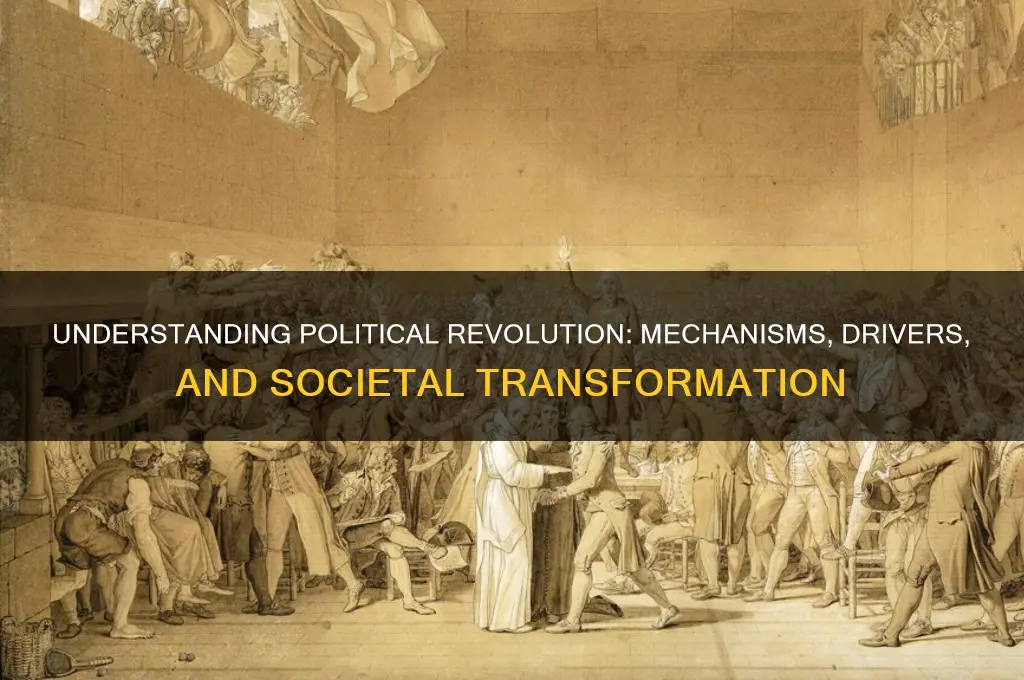

Political revolution is a profound and transformative process through which societies fundamentally alter their governing structures, power dynamics, and ideological frameworks. It typically arises from widespread dissatisfaction with existing systems, often fueled by economic inequality, social injustice, or political oppression. Revolutions are driven by collective action, as diverse groups mobilize to challenge and overthrow established authorities, replacing them with new institutions or ideologies that align with their vision of a more just and equitable society. This process involves not only the physical act of overthrowing a regime but also the intellectual and cultural shifts that redefine norms, values, and the social contract. While revolutions can lead to significant progress, they are often marked by uncertainty, conflict, and the risk of unintended consequences, making them complex and multifaceted phenomena in the study of political change.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Causes | Economic inequality, political oppression, social injustice, lack of representation, or external influences. |

| Mobilization | Grassroots organizing, mass protests, strikes, and use of social media to spread ideas. |

| Leadership | Emergence of charismatic leaders or collective leadership guiding the movement. |

| Ideology | Clear vision for change, often rooted in socialism, liberalism, nationalism, or other political philosophies. |

| Violence | Can be nonviolent (e.g., civil disobedience) or violent (e.g., armed struggle), depending on context. |

| International Support | External backing from other nations, organizations, or global movements can influence success. |

| State Response | Government may suppress, negotiate, or collapse in response to revolutionary pressure. |

| Transition Phase | Period of instability, power vacuums, and potential for counter-revolution or reform. |

| Outcome | Regime change, constitutional reforms, or failure, leading to restoration of the old order. |

| Long-Term Impact | Transformation of political systems, societal norms, and economic structures. |

| Examples | French Revolution (1789), Russian Revolution (1917), Arab Spring (2010-2012). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Causes of Revolution: Economic inequality, political oppression, social injustice, and lack of representation spark revolutionary movements

- Mobilization Strategies: Grassroots organizing, protests, social media, and alliances build mass support for revolutionary change

- Leadership Dynamics: Charismatic leaders, collective leadership, or decentralized structures guide and sustain revolutionary efforts

- Tactics and Methods: Nonviolent resistance, armed struggle, civil disobedience, and general strikes drive revolutionary action

- Post-Revolution Governance: Establishing new political systems, institutions, and policies to achieve revolutionary goals and stability

Causes of Revolution: Economic inequality, political oppression, social injustice, and lack of representation spark revolutionary movements

Economic inequality often serves as the kindling for revolutionary fires. When wealth concentrates in the hands of a few while the majority struggles to meet basic needs, resentment festers. Consider the French Revolution, where the opulent lifestyles of the aristocracy contrasted sharply with the poverty of the Third Estate. Modern examples include the Arab Spring, where rising food prices and unemployment fueled widespread discontent. To address this, policymakers must implement progressive taxation, invest in social safety nets, and enforce wage equity. Ignoring these measures risks creating a tinderbox of frustration, where even a small spark can ignite mass unrest.

Political oppression acts as a catalyst, transforming discontent into organized resistance. When governments suppress dissent, censor media, or rig elections, they alienate their citizens. The Iranian Revolution of 1979 exemplifies this, as the Shah’s authoritarian rule and disregard for civil liberties galvanized opposition. Similarly, in Hong Kong, the extradition bill controversy highlighted the dangers of eroding autonomy and freedoms. To prevent such outcomes, governments should prioritize transparency, protect free speech, and ensure fair electoral processes. Without these safeguards, oppressed populations will inevitably seek radical change, often through revolutionary means.

Social injustice breeds revolutions by marginalizing entire groups based on race, gender, or religion. The American Civil Rights Movement, for instance, was a response to systemic racism and segregation. In contemporary India, caste-based discrimination continues to fuel protests and calls for reform. Addressing these issues requires not only legal reforms but also cultural shifts. Education, affirmative action, and community engagement are essential tools to dismantle entrenched biases. Failure to act perpetuates cycles of exclusion, pushing marginalized groups toward revolutionary action as a last resort.

Lack of representation in governance alienates citizens and undermines legitimacy. When political systems exclude certain demographics—whether through gerrymandering, voter suppression, or elitist structures—people feel disenfranchised. The 2019 Sudanese Revolution emerged from decades of authoritarian rule that ignored the needs of the populace. To foster inclusivity, governments must adopt proportional representation, lower barriers to political participation, and amplify marginalized voices. Practical steps include lowering voting ages to 16, implementing quotas for underrepresented groups, and leveraging digital platforms for civic engagement. Without genuine representation, the gap between rulers and ruled widens, setting the stage for revolutionary upheaval.

Katrina Crisis: Political Failures or Natural Disaster Mismanagement?

You may want to see also

Mobilization Strategies: Grassroots organizing, protests, social media, and alliances build mass support for revolutionary change

Political revolutions are not spontaneous eruptions but the culmination of deliberate, strategic mobilization. At the heart of this process lies grassroots organizing, the quiet yet relentless work of building local networks that foster trust, shared purpose, and collective action. Unlike top-down movements, grassroots efforts tap into existing community structures—neighborhood associations, religious groups, labor unions—to create a foundation of engaged citizens. For instance, the Civil Rights Movement in the United States thrived on local chapters of the NAACP and church-based organizing, which provided both logistical support and moral grounding. To replicate this, organizers must focus on listening to community needs, identifying natural leaders, and creating spaces where people feel empowered to act. A practical tip: start with small, achievable goals, like a community clean-up or a petition drive, to build momentum and demonstrate the power of collective effort.

Protests serve as the visible pulse of revolutionary movements, transforming latent discontent into public outrage. They are not merely symbolic acts but strategic tools designed to disrupt the status quo, capture media attention, and galvanize broader support. The 2019 pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong exemplify this, where organizers employed a "be water" strategy—fluid, decentralized, and unpredictable—to sustain pressure on the government. When planning protests, consider timing, location, and messaging carefully. For maximum impact, coordinate actions with other mobilization efforts, such as social media campaigns or legislative lobbying. A caution: protests must remain nonviolent to maintain moral high ground and avoid alienating potential allies. Research shows that nonviolent movements are twice as likely to succeed as violent ones, making discipline and training in peaceful tactics essential.

Social media has revolutionized mobilization by enabling rapid dissemination of information, coordination of actions, and amplification of revolutionary narratives. Platforms like Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok played pivotal roles in the Arab Spring and Black Lives Matter movements, allowing activists to bypass traditional media gatekeepers and reach global audiences. To leverage social media effectively, focus on storytelling—share personal testimonies, visuals, and actionable calls to participation. Use hashtags strategically to create a unified campaign identity and monitor engagement metrics to refine messaging. However, beware of the echo chamber effect: algorithms often reinforce existing beliefs rather than fostering dialogue. To counter this, engage with diverse audiences, address counterarguments, and collaborate with influencers who can bridge ideological divides.

Alliances are the backbone of sustained revolutionary movements, transforming isolated efforts into a unified force capable of challenging entrenched power structures. The Rainbow Coalition, formed by Jesse Jackson in the 1980s, brought together African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, women, and LGBTQ+ groups to advocate for economic and social justice. Building alliances requires humility, compromise, and a shared vision that transcends individual interests. Start by identifying potential partners based on overlapping goals, then engage in open dialogue to address differences and build trust. A practical step: create joint action plans that highlight each ally’s strengths while advancing the collective agenda. Remember, alliances are not static—they require ongoing maintenance, transparency, and a willingness to adapt as circumstances evolve.

Together, grassroots organizing, protests, social media, and alliances form a multifaceted toolkit for building mass support for revolutionary change. Each strategy complements the others, creating a synergy that amplifies impact and sustains momentum. Grassroots efforts provide the foundation, protests the visibility, social media the reach, and alliances the strength. By mastering these mobilization strategies, movements can navigate the complexities of political revolution, turning dissent into transformative action. The key takeaway: revolution is not an event but a process, and its success depends on the deliberate, strategic integration of these tactics.

Egalitarianism as a Political Philosophy: Principles, Impact, and Debates

You may want to see also

Leadership Dynamics: Charismatic leaders, collective leadership, or decentralized structures guide and sustain revolutionary efforts

The role of leadership in political revolutions is a critical factor that can determine their trajectory and outcome. Charismatic leaders, with their magnetic personalities and compelling visions, often emerge as the face of revolutionary movements. Think of figures like Nelson Mandela, whose unwavering commitment to ending apartheid in South Africa inspired millions to join the struggle. These leaders possess an extraordinary ability to articulate a shared purpose, galvanizing diverse groups into a unified force. However, the reliance on a single individual can be a double-edged sword. The movement's success becomes intricately tied to the leader's fate, as seen in the aftermath of Che Guevara's death, which significantly impacted the global revolutionary landscape.

In contrast, collective leadership offers a more resilient approach, distributing power among a group of individuals. This model is exemplified by the Zapatista movement in Mexico, where a diverse council of commanders makes decisions collectively. By sharing leadership, the movement ensures continuity and reduces the risk of a single point of failure. Collective leadership fosters a sense of shared ownership, empowering members and encouraging active participation. It also allows for a more inclusive decision-making process, incorporating diverse perspectives and experiences. This structure is particularly effective in sustaining long-term revolutionary efforts, as it can adapt to changing circumstances and maintain momentum even in the face of repression.

Decentralized structures take this concept further, advocating for a leaderless revolution. This approach is characterized by autonomous cells or networks operating independently but united by a common ideology. The Arab Spring, particularly in its early stages, demonstrated the power of decentralized organization. Social media played a pivotal role in mobilizing people, allowing for rapid coordination without a central command. This model is highly adaptable and resilient, making it difficult for authorities to suppress. However, the lack of a centralized leadership can also lead to challenges in strategic planning and maintaining a cohesive vision.

Each leadership dynamic has its advantages and potential pitfalls. Charismatic leaders can inspire and unite, but their movements may struggle to survive without them. Collective leadership provides stability and inclusivity, yet it might face challenges in decision-making speed and unity of vision. Decentralized structures offer adaptability and resilience, but they may lack the strategic focus and long-term planning necessary for sustained revolution.

In the complex world of political revolutions, the choice of leadership style is not merely a structural decision but a strategic one. It involves understanding the context, the nature of the struggle, and the capabilities of the movement's members. A successful revolution often requires a nuanced approach, perhaps even a hybrid model, that leverages the strengths of each leadership dynamic. For instance, a charismatic leader might initiate the movement, but the transition to collective leadership could ensure its longevity. As revolutions are inherently unpredictable, the ability to adapt leadership strategies becomes a crucial skill for any revolutionary endeavor.

Mastering Politoed's SOS Strategy: Tips for Summoning Success in Pokémon

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$14.47 $17.95

$9.99 $9.99

Tactics and Methods: Nonviolent resistance, armed struggle, civil disobedience, and general strikes drive revolutionary action

Political revolutions are not monolithic events but diverse phenomena shaped by the tactics and methods employed. Among these, nonviolent resistance, armed struggle, civil disobedience, and general strikes stand out as pivotal drivers of change. Each method carries distinct advantages, risks, and historical precedents, offering a toolkit for movements seeking to overthrow or transform existing power structures. Understanding these tactics is essential for strategizing effective revolutionary action.

Nonviolent resistance, popularized by figures like Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., leverages moral persuasion and mass mobilization to challenge authority. This method relies on boycotts, sit-ins, and peaceful protests to disrupt the status quo while maintaining ethical high ground. For instance, the Indian independence movement used salt marches and non-cooperation campaigns to undermine British colonial rule. Nonviolent resistance is particularly effective in gaining international sympathy and delegitimizing oppressive regimes. However, it demands discipline and widespread participation, as its success hinges on sustained public engagement. Movements adopting this approach must prepare for state repression and cultivate resilience among participants.

In contrast, armed struggle represents a more confrontational approach, often employed when nonviolent methods fail or are deemed insufficient. Revolutionary groups like the Cuban rebels led by Fidel Castro or the Algerian FLN have used guerrilla warfare to challenge entrenched power. Armed struggle can galvanize supporters and create tangible territorial gains, but it carries significant risks, including civilian casualties, international condemnation, and internal fragmentation. This method requires careful planning, resource management, and a clear ideological framework to avoid devolving into chaos. It is most effective in contexts where the state’s legitimacy is already weakened, and the population is willing to endure prolonged conflict.

Civil disobedience bridges the gap between nonviolence and armed struggle by openly defying unjust laws or policies. Examples include the Montgomery Bus Boycott in the U.S. civil rights movement and the anti-apartheid campaigns in South Africa. This tactic disrupts societal norms and forces authorities to either enforce laws brutally, exposing their tyranny, or concede to demands. Civil disobedience is highly adaptable, ranging from symbolic acts like hunger strikes to mass refusals to pay taxes. However, participants must be prepared for arrest, violence, and economic retaliation. Its strength lies in its ability to provoke systemic change while maintaining a moral stance.

General strikes, another powerful tool, paralyze economies and governments by halting labor across sectors. The 1988 Burmese Uprising and the 2019 Catalan protests demonstrate how strikes can cripple regimes and amplify revolutionary demands. Unlike localized protests, general strikes require broad coordination among workers, unions, and civil society. They are particularly effective in capitalist systems, where economic disruption directly threatens ruling elites. However, prolonged strikes risk alienating the public if essential services are affected. Organizers must balance pressure on the state with public support, often framing strikes as acts of collective self-defense rather than mere disruption.

Each of these tactics—nonviolent resistance, armed struggle, civil disobedience, and general strikes—serves distinct purposes and suits specific contexts. Movements must assess their goals, resources, and the nature of the regime they oppose to choose the most effective approach. Hybrid strategies, combining elements of these methods, are often the most successful, as seen in the Arab Spring or the Velvet Revolution. Ultimately, the key to revolutionary action lies not just in the tactics themselves but in their strategic application, adaptability, and alignment with the aspirations of the people they aim to liberate.

The Ugly Truth: How Bad Are the Politics Today?

You may want to see also

Post-Revolution Governance: Establishing new political systems, institutions, and policies to achieve revolutionary goals and stability

The success of a political revolution hinges not on the overthrow of the old regime, but on the ability to construct a stable and effective post-revolution governance system. This phase is fraught with challenges, as revolutionaries must transition from a mindset of opposition to one of state-building, often with limited experience in governance and amidst societal upheaval.

A critical first step is establishing legitimacy. The new government must demonstrate its authority and win the trust of the population. This can be achieved through inclusive processes like drafting a new constitution through widespread consultation, holding free and fair elections, and ensuring representation of diverse groups within the new political institutions. For instance, the post-apartheid South African government prioritized truth and reconciliation commissions to address past injustices and foster national unity.

Simultaneously, the new regime must address the immediate needs of the population, which often fueled the revolution in the first place. This involves implementing policies that tackle economic inequality, social injustice, and political disenfranchisement. A revolutionary government in a country with high unemployment might prioritize job creation programs, land reform, and universal access to basic services like healthcare and education. However, balancing immediate demands with long-term sustainability is crucial. Hasty and poorly planned policies can lead to economic instability and disillusionment.

Building robust institutions is another cornerstone of post-revolution governance. These institutions, such as an independent judiciary, a professional civil service, and accountable security forces, are essential for upholding the rule of law, preventing corruption, and ensuring the stability of the new system. The challenge lies in creating institutions that are both effective and representative of the revolutionary ideals. This often requires a delicate balance between appointing experienced technocrats and incorporating revolutionary cadres who embody the spirit of the movement.

A comparative analysis reveals that revolutions that prioritize inclusive institution-building and pragmatic policy-making are more likely to achieve long-term stability. The post-revolutionary governments of Portugal and Spain, for example, successfully transitioned to democratic systems by fostering consensus-building and gradually implementing economic reforms. In contrast, revolutions that succumb to factionalism, ideological rigidity, or neglect institution-building often descend into chaos or authoritarianism.

Ultimately, establishing post-revolution governance is a complex and iterative process. It requires a combination of visionary leadership, pragmatic policymaking, and a commitment to inclusivity and accountability. The ability to navigate these challenges determines whether a revolution fulfills its promise of a better future or succumbs to the pitfalls of instability and disillusionment.

Is Political Patronage Legal? Exploring Ethics and Legal Boundaries

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political revolution is a fundamental change in the political power structure, often involving the overthrow or replacement of an existing government or regime. It typically occurs when a significant portion of the population mobilizes to challenge the status quo, driven by grievances such as inequality, oppression, or lack of representation.

A political revolution often begins with widespread dissatisfaction among the population, fueled by economic, social, or political injustices. It is usually sparked by catalysts such as protests, mass movements, or charismatic leaders who articulate a vision for change. Organizing, communication, and solidarity among diverse groups play crucial roles in building momentum.

The key stages of a political revolution typically include: (1) Mobilization, where people organize and protest against the existing system; (2) Crisis, when the government loses legitimacy or control; (3) Transition, where power shifts to new leaders or institutions; and (4) Consolidation, where the new regime establishes stability and implements reforms. Success depends on factors like leadership, external support, and the ability to address root causes.