A biased political poll is a survey designed or conducted in a way that skews results to favor a particular candidate, party, or viewpoint, often undermining its credibility and accuracy. Bias can stem from various factors, such as flawed sampling methods that fail to represent the population, leading questions that influence respondents' answers, or selective reporting of data to highlight predetermined outcomes. Additionally, timing, question wording, and even the sponsor of the poll can introduce bias, making it essential for consumers to critically evaluate the methodology and context of such surveys. Understanding these biases is crucial for interpreting poll results objectively and avoiding misinformation in political discourse.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Leading Questions | Phrased to influence responses (e.g., "Do you support the president’s excellent policies?"). |

| Unrepresentative Sample | Over-represents or under-represents specific demographics (e.g., only urban voters). |

| Loaded Language | Uses emotionally charged or biased wording (e.g., "radical agenda" vs. "progressive reforms"). |

| Lack of Randomization | Samples are not randomly selected, leading to skewed results. |

| Small Sample Size | Insufficient sample size to accurately represent the population. |

| Omitted or Misleading Options | Excludes key candidates or provides misleading answer choices. |

| Timing Bias | Conducted at a time that favors one side (e.g., immediately after a positive event for a candidate). |

| Sponsorship Bias | Funded by a politically aligned group, influencing methodology or results. |

| Non-Response Bias | Ignores or misrepresents those who choose not to participate. |

| Push Polling | Disguised as a poll but aims to spread negative information about a candidate. |

| Misleading Context | Presents data out of context or with misleading comparisons. |

| Lack of Transparency | Does not disclose methodology, funding sources, or potential conflicts of interest. |

| Overemphasis on Outliers | Highlights extreme or unrepresentative responses to skew perception. |

| Biased Weighting | Adjusts data to favor a particular demographic or viewpoint unfairly. |

| False Dichotomies | Forces respondents into extreme choices without neutral or moderate options. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Leading Questions: Framing queries to sway responses toward a specific political viewpoint or candidate

- Non-Representative Samples: Excluding or overrepresenting demographic groups to skew poll results unfairly

- Push Polling: Using loaded questions to spread negative information about a candidate or party

- Timing Manipulation: Conducting polls at times favorable to one side, ignoring broader public sentiment

- Weighted Data Misuse: Adjusting results without transparency to favor predetermined political outcomes

Leading Questions: Framing queries to sway responses toward a specific political viewpoint or candidate

Leading questions in political polls are a subtle yet powerful tool for manipulating public opinion. By framing a query in a way that nudges respondents toward a specific answer, pollsters can skew results to favor a particular candidate or ideology. For instance, asking, "Do you support Candidate X, who has a proven track record of lowering taxes and creating jobs?" presupposes positive attributes and makes it harder for respondents to answer negatively. This technique exploits cognitive biases, such as the tendency to agree with statements that align with preexisting beliefs, effectively turning a poll into a persuasion instrument rather than an objective measure of public sentiment.

To craft a leading question, pollsters often embed assumptions or loaded language that primes respondents to answer in a certain way. For example, instead of asking, "What is your opinion on the current administration's handling of the economy?" a biased poll might ask, "How concerned are you about the current administration’s failure to address rising inflation?" The latter frames the issue negatively, presupposing failure, and directs respondents toward expressing concern. Such questions are not neutral; they are designed to elicit specific reactions, often by appealing to emotions like fear or outrage, which can disproportionately influence less-informed or undecided voters.

A comparative analysis of leading questions reveals their effectiveness across demographics. Younger voters, aged 18–25, are particularly susceptible to leading questions due to their lower political engagement and higher reliance on surface-level information. For instance, a question like, "Should the government prioritize funding for renewable energy to combat climate change, a crisis affecting our future?" resonates strongly with this age group, as it aligns with their values and uses emotive language. In contrast, older voters, aged 55 and above, may be more resistant to such tactics but can still be swayed by questions that appeal to their concerns about stability, such as, "Do you believe Candidate Y’s plan to cut social security benefits is fair to retirees?" Tailoring leading questions to specific age groups amplifies their impact, making them a strategic tool in targeted polling campaigns.

To avoid falling victim to leading questions, respondents should scrutinize the wording of poll queries. Look for loaded terms, presuppositions, or emotional appeals that signal bias. For example, if a question begins with "Despite the overwhelming evidence of corruption," it is likely leading you toward a negative opinion. Additionally, consider the context in which the poll is being conducted. Who is sponsoring it? What is their political leaning? Being aware of these factors can help you interpret the results more critically. For pollsters aiming to maintain integrity, the solution is straightforward: use neutral, balanced language and avoid embedding assumptions in questions. For instance, instead of asking, "How much do you support Candidate Z’s radical agenda?" ask, "What is your opinion on Candidate Z’s policy proposals?" Such clarity ensures that polls reflect genuine public opinion rather than engineered outcomes.

In conclusion, leading questions are a pervasive issue in political polling, capable of distorting results and influencing public perception. By understanding their mechanics—how they embed assumptions, appeal to emotions, and target specific demographics—both respondents and pollsters can take steps to mitigate their impact. For voters, critical thinking and awareness are key; for pollsters, ethical question design is essential. In an era where public opinion shapes policy and elections, ensuring the integrity of polls is not just a technical concern but a democratic imperative.

Understanding Clinton's Political Ideology: Liberalism, Pragmatism, and Centrism Explained

You may want to see also

Non-Representative Samples: Excluding or overrepresenting demographic groups to skew poll results unfairly

Biased political polls often stem from non-representative samples, where certain demographic groups are either excluded or overrepresented. This deliberate skewing undermines the poll’s accuracy, painting a distorted picture of public opinion. For instance, a poll that oversamples urban voters while neglecting rural populations will overstate support for policies favored by city dwellers, such as public transportation funding. Conversely, excluding younger voters, who tend to lean more progressive, can artificially inflate conservative viewpoints. Such manipulations render the poll’s findings unreliable, as they fail to reflect the diversity of the electorate.

To avoid this pitfall, pollsters must ensure their samples mirror the demographic makeup of the target population. This includes balancing factors like age, gender, race, education level, and geographic location. For example, if a poll aims to represent the U.S. electorate, it should include approximately 50% women, 12% Black Americans, and 18% Hispanic Americans, based on census data. Failing to account for these proportions can lead to skewed results. Practical tools like stratified sampling, where subgroups are proportionally represented, can help achieve this balance. Without such measures, polls risk becoming tools of misinformation rather than instruments of insight.

Consider the 2016 U.S. presidential election, where many polls underestimated support for Donald Trump. One contributing factor was the underrepresentation of non-college-educated white voters, a key demographic in his base. These voters were less likely to respond to surveys, leading to samples that overrepresented college-educated voters, who leaned more toward Hillary Clinton. This oversight created a false narrative of Clinton’s lead, highlighting the dangers of non-representative sampling. Pollsters must actively address response biases by employing techniques like weighting or targeted outreach to underrepresented groups.

The consequences of non-representative samples extend beyond election predictions. They can influence policy decisions, media narratives, and public perception. For example, a poll overrepresenting high-income households might suggest widespread support for tax cuts, prompting policymakers to prioritize such measures. In reality, lower-income groups, who are often excluded from such polls, may oppose these policies. This disconnect between poll results and actual public sentiment undermines democratic processes. To mitigate this, pollsters should transparently disclose their sampling methods and limitations, allowing consumers to critically evaluate the data.

Ultimately, creating a representative sample requires diligence, resources, and ethical commitment. Pollsters must invest in robust methodologies, such as random sampling and demographic weighting, to ensure fairness. Additionally, they should acknowledge inherent challenges, like non-response bias, and take steps to minimize them. For the public, understanding these issues fosters skepticism of polls that lack transparency or methodological rigor. By addressing non-representative samples, we can restore trust in polling as a vital tool for understanding public opinion.

Stay Focused: Why Avoiding Politics Can Strengthen Your Relationships

You may want to see also

Push Polling: Using loaded questions to spread negative information about a candidate or party

Push polling is a covert tactic that masquerades as legitimate political research but is, in fact, a tool for smearing opponents. Unlike traditional polls that aim to gauge public opinion, push polls are designed to influence it by embedding negative information within seemingly neutral questions. For instance, a push poll might ask, “If you knew that Candidate X had been accused of embezzlement, would you still vote for them?” The question itself plants the seed of doubt, regardless of the respondent’s answer, effectively spreading unverified or exaggerated claims under the guise of inquiry.

To execute a push poll, operatives often use high-volume calling strategies, targeting thousands of voters in a short period. The goal isn’t to collect data but to disseminate damaging narratives. For example, during a 2000 U.S. Senate race, a push poll asked voters, “If you knew that Candidate Y had supported cuts to veterans’ benefits, would that change your vote?” The statement about veterans’ benefits was either false or taken out of context, but the damage was done. Such polls exploit cognitive biases, like the availability heuristic, where repeated exposure to negative information makes it seem more credible.

Identifying a push poll requires vigilance. Legitimate surveys are brief and focused, whereas push polls often include lengthy, leading questions that feel more like a monologue than a dialogue. If a caller spends more time talking than listening, or if the questions seem designed to provoke rather than inquire, it’s likely a push poll. Voters should hang up and report the call to election authorities. Organizations like the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) condemn push polling as unethical, but enforcement remains challenging due to its clandestine nature.

The effectiveness of push polls lies in their ability to bypass critical thinking. By framing negative information as a question, they create an illusion of legitimacy. For instance, a question like, “How concerned are you about Candidate Z’s ties to foreign lobbyists?” implies guilt without providing evidence. To counter this, voters should fact-check claims independently and rely on trusted news sources. Campaigns can also preemptively educate their supporters about push polling tactics, reducing their impact.

In conclusion, push polling is a manipulative strategy that undermines fair political discourse. By recognizing its hallmarks—loaded questions, high-volume calls, and a lack of genuine data collection—voters can protect themselves from its influence. While it remains a persistent issue, awareness and critical thinking are powerful tools to combat this form of political deception.

Global Politics Unveiled: Power, Diplomacy, and Shifting World Orders

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$153.76 $199.99

Timing Manipulation: Conducting polls at times favorable to one side, ignoring broader public sentiment

Polls conducted immediately after a high-profile event often capture an emotional, not rational, snapshot of public opinion. For instance, a survey taken hours after a politician’s controversial speech might show inflated disapproval ratings, as respondents react to the heat of the moment rather than reflecting on long-term implications. This timing skews results toward the side that benefits from the immediate emotional fallout, ignoring the broader, more nuanced sentiment that emerges with time.

To avoid falling victim to timing manipulation, scrutinize when a poll was conducted relative to key events. A poll released during a scandal will naturally tilt negative, while one taken during a policy success will skew positive. Cross-reference the timing with a timeline of relevant events to assess whether the poll captures a fleeting reaction or a sustained trend. For example, a poll on healthcare policy taken during a major health crisis may overrepresent anxiety, while one conducted months later might reflect more balanced, considered opinions.

Consider this scenario: A political campaign releases a poll showing their candidate leading by 10 points, but the survey was conducted the day after their opponent’s gaffe went viral. This timing exploits the opponent’s temporary vulnerability, presenting a distorted picture of public support. To counter such manipulation, look for polls that average data over several weeks or months, smoothing out short-term fluctuations and providing a more accurate measure of public sentiment.

Timing manipulation isn’t just about when a poll is conducted, but also when its results are released. Campaigns often withhold unfavorable polls or delay their publication until a more opportune moment. For instance, a poll showing declining support might be shelved until after a successful debate performance, making the decline seem less significant. Always question the timing of a poll’s release and whether it aligns with a strategic narrative rather than genuine public opinion.

To guard against timing bias, demand transparency in polling methodology. Legitimate polls disclose their fieldwork dates, sample size, and margin of error. If these details are missing, treat the results with skepticism. Additionally, compare polls conducted at different times to identify patterns and outliers. A single poll taken at a strategically advantageous moment should never be the sole basis for understanding public sentiment. Instead, look for consistency across multiple surveys conducted under varying conditions.

Buddhism and Politics: Exploring Monks' Engagement in Secular Affairs

You may want to see also

Weighted Data Misuse: Adjusting results without transparency to favor predetermined political outcomes

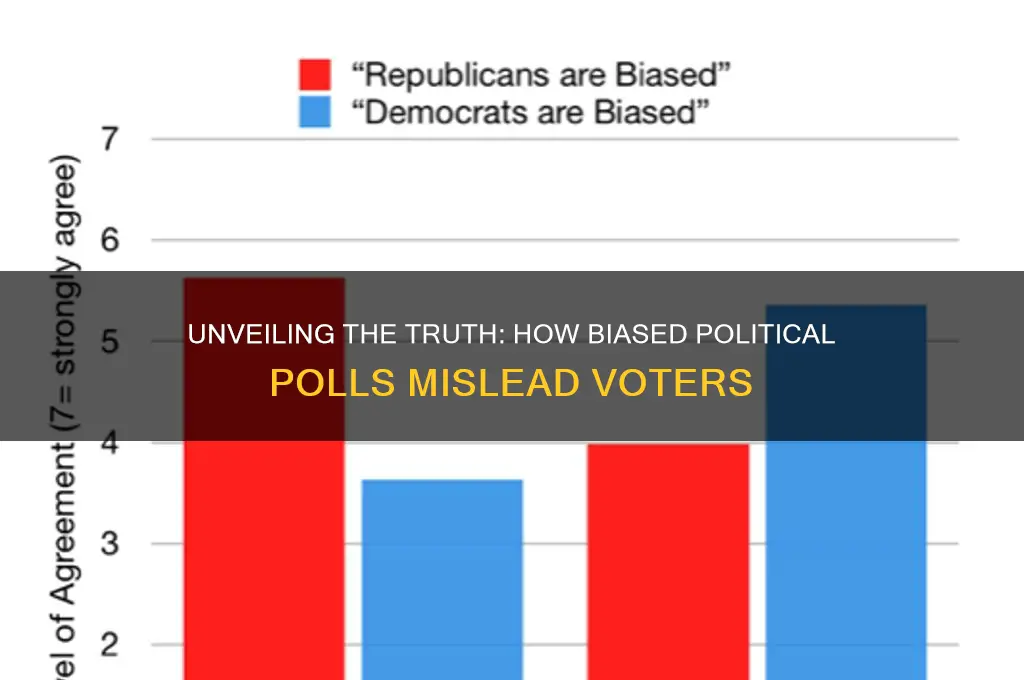

Political polls often employ weighting to ensure their samples reflect the population they aim to represent. This involves adjusting raw data to account for factors like age, gender, or race. However, when weighting becomes a tool for manipulation rather than accuracy, it morphs into a dangerous practice: weighted data misuse. This occurs when pollsters adjust results without transparency, skewing outcomes to favor predetermined political agendas.

Consider a hypothetical scenario: a polling firm conducts a survey on public opinion regarding a controversial policy. The raw data shows a slight majority opposing the policy. However, the firm, under pressure from a political client, decides to overweight responses from younger demographics, known to be more supportive of the policy, while underweighting older respondents. This selective weighting, done without disclosing the methodology or justification, artificially inflates support for the policy, presenting a distorted picture to the public.

The lack of transparency in such practices is particularly insidious. Pollsters may claim their weighting methods are proprietary or too complex for public understanding, effectively shielding their manipulations from scrutiny. This opacity undermines the very purpose of polling: to provide an accurate snapshot of public sentiment. Without clear disclosure of weighting criteria and rationale, polls become vehicles for propaganda rather than tools for informed decision-making.

To guard against weighted data misuse, consumers of political polls must demand transparency. Pollsters should be required to publish detailed methodologies, including the specific weighting schemes used and the rationale behind them. Additionally, independent audits of polling practices can help ensure accountability. By insisting on clarity and openness, we can mitigate the risk of polls being weaponized to manipulate public opinion and instead restore their role as reliable gauges of societal attitudes.

Mastering Political Scheduling: A Comprehensive Guide to Effective Campaign Planning

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A biased political poll is a survey designed or conducted in a way that favors a particular political outcome, candidate, or viewpoint, often due to flawed methodology, leading questions, or selective sampling.

A political poll can be biased through skewed sampling (e.g., excluding certain demographics), loaded or leading questions, weighting responses unfairly, or excluding key groups, such as undecided voters or third-party supporters.

Biased political polls can mislead the public, influence voter behavior, and distort media narratives, undermining the integrity of democratic processes and public trust in polling data.

Look for transparency in methodology, sample size, demographic representation, question wording, and the sponsoring organization. Lack of clarity or obvious skews in these areas may indicate bias.