Punch and Judy shows, a traditional form of British puppetry, have long been a subject of debate regarding their political undertones. Originating in the 17th century, these performances often feature slapstick humor and exaggerated characters, but beneath the surface, they frequently reflect societal and political issues of their time. The titular characters, Mr. Punch and his wife Judy, along with other figures like the Devil and the Constable, engage in chaotic and morally ambiguous scenarios that can be interpreted as commentary on authority, justice, and human behavior. While some argue that the shows are merely entertainment, others contend that they subtly critique power structures and social norms, making them a fascinating lens through which to explore the intersection of politics and popular culture.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin | British satirical magazine founded in 1841. |

| Political Focus | Critiqued political figures, policies, and societal issues of its time. |

| Satirical Style | Used humor, caricatures, and irony to mock political leaders and events. |

| Key Targets | Politicians, monarchs, and government institutions. |

| Influence | Shaped political discourse and public opinion in 19th-century Britain. |

| Notable Contributors | Included artists like John Leech and writers like Charles Dickens. |

| Legacy | Inspired modern political satire and cartooning. |

| Political Alignment | Generally liberal, often opposing Tory policies and corruption. |

| Visual Medium | Relied heavily on illustrations and cartoons to convey messages. |

| Impact on Media | Pioneered the use of satire in journalism and political commentary. |

| Historical Context | Active during significant political events like the Reform Acts. |

| Criticism | Faced backlash from targeted politicians and conservative groups. |

| Modern Relevance | Considered a precursor to modern political satire shows and publications. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Punch's Satirical Targets: Politicians, Policies, and Scandals

Punch’s satirical edge was sharpened by its relentless targeting of politicians, policies, and scandals, making it a formidable force in 19th-century British political discourse. Unlike modern satire, which often relies on rapid-fire jokes, Punch employed meticulous caricatures and biting commentary to expose the follies of the powerful. Its most famous target, Prime Minister William Gladstone, was depicted as a manipulative figure, his policies dissected with a scalpel-like precision. For instance, Punch’s cartoon “The British Lion’s Venomous Tooth” critiqued Gladstone’s foreign policy by portraying him as a lion with a broken fang, symbolizing Britain’s weakened global stance. This approach not only entertained but educated readers, turning political complexities into accessible, visual narratives.

To craft effective satire like Punch, start by identifying a politician’s most glaring contradiction or scandal. For example, Punch often highlighted Disraeli’s flamboyant persona against his pragmatic policies, creating a character both admired and ridiculed. Next, use exaggeration and symbolism to amplify the absurdity. A modern equivalent might depict a leader’s empty promises as a balloon inflating until it bursts. Pair this with sharp, concise text—Punch’s captions were often just a few words, yet devastatingly effective. Finally, ensure the satire is rooted in truth; Punch’s credibility stemmed from its factual basis, avoiding the trap of mere mockery.

Comparing Punch to contemporary political satire reveals both continuity and evolution. While Punch focused on individual politicians and their policies, modern satire often targets systemic issues, such as corruption or inequality. However, the core strategy remains: use humor to disarm and engage. Punch’s legacy lies in its ability to make readers question authority, a lesson today’s satirists can emulate. For instance, instead of caricaturing a single leader, focus on the absurdity of a policy’s implementation—say, a healthcare reform that benefits only the wealthy. By blending historical tactics with modern themes, satirists can create work that resonates across eras.

One of Punch’s most enduring contributions was its role in shaping public opinion during scandals. The magazine’s coverage of the 1876 “Bulgarian Atrocities” controversy, where it criticized Disraeli’s indifference, galvanized public outrage and influenced policy shifts. To replicate this impact, satirists should target scandals with broad societal implications, such as environmental neglect or corporate malfeasance. Use recurring characters or motifs to build a narrative arc, as Punch did with its “John Bull” figure, embodying the British everyman. By framing scandals as relatable stories, satire can transform passive readers into active citizens, proving that humor is not just entertainment—it’s a tool for change.

Understanding Identity Politics: Exploring Its Impact on Society and Culture

You may want to see also

Historical Context: Punch's Role in 19th-Century British Politics

In the 19th century, *Punch*, the iconic British satirical magazine, wielded significant influence over public opinion and political discourse. Founded in 1841 by Henry Mayhew and engraver Ebenezer Landells, it quickly became a platform for sharp wit and biting commentary on the era’s social and political issues. Its cartoons and articles targeted the foibles of the ruling class, the absurdities of bureaucracy, and the moral dilemmas of industrialization. Through its pages, *Punch* not only entertained but also educated its middle-class readership, shaping their views on everything from electoral reform to imperial expansion.

Consider the magazine’s role during the 1848 revolutions across Europe. While Britain remained relatively stable, *Punch* used this moment to critique domestic complacency and the government’s handling of social unrest. Its cartoons often depicted Prime Minister Lord John Russell as a hesitant leader, unable to address the growing demands for reform. For instance, a famous illustration showed Russell as a tightrope walker, symbolizing his precarious balance between radical change and conservative resistance. This visual satire was more than humor—it was a tool to hold power to account and encourage readers to question authority.

Punch’s political impact was amplified by its accessibility. Sold for a shilling, it was affordable for the burgeoning middle class, who sought both entertainment and insight into current affairs. Its use of caricatures, such as John Leech’s iconic depictions of John Bull (the personification of England) and the greedy politician “Mr. Briggs,” made complex political issues relatable. These characters became cultural touchstones, allowing readers to engage with politics in a way that felt personal and immediate. For example, during the Crimean War (1853–1856), Punch’s relentless criticism of military mismanagement helped fuel public outrage, contributing to the eventual fall of the Aberdeen ministry.

However, *Punch*’s political stance was not without contradictions. While it championed liberal causes like the expansion of suffrage, it also reflected the prejudices of its time, particularly regarding imperialism and race. Its cartoons often caricatured colonized peoples in demeaning ways, reinforcing British superiority. This duality highlights the magazine’s role as both a progressive force and a product of its era’s limitations. To understand *Punch*’s legacy, one must recognize its ability to challenge authority while also perpetuating dominant ideologies.

In practice, studying *Punch* offers a unique lens into 19th-century British politics. For educators or historians, incorporating its cartoons into lessons can make abstract political concepts tangible. For instance, pairing a *Punch* illustration of the 1867 Reform Act debates with primary sources from Parliament allows students to see how satire both reflected and influenced public opinion. Similarly, analyzing its coverage of the Irish Famine or the Opium Wars can spark discussions about media responsibility and bias. By treating *Punch* as a primary source, we gain insight into how humor and art shaped political consciousness during a transformative century.

Does Politico Support Trump? Analyzing the Media's Stance and Coverage

You may want to see also

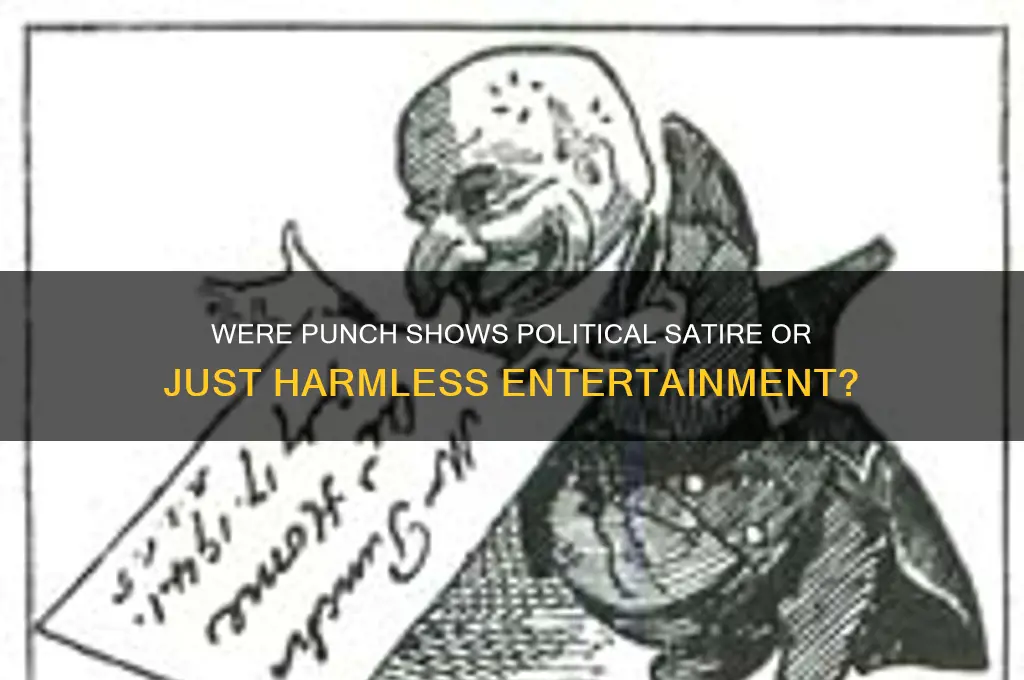

Cartoons vs. Editorials: Visual and Written Political Commentary

Political cartoons and editorials have long been stalwarts of media, each wielding distinct tools to dissect and critique power. Cartoons, with their visual immediacy, rely on symbolism, exaggeration, and satire to deliver a punch in a single frame. Think of Thomas Nast’s depictions of Boss Tweed in the 19th century or modern cartoons skewering political figures with animal metaphors or distorted features. These images bypass language barriers, making them universally accessible, but their impact hinges on cultural literacy—a reader must recognize the symbols to grasp the critique. Editorials, on the other hand, deploy words to argue, explain, and persuade. They offer depth, nuance, and context, often appealing to logic and evidence. While cartoons aim for the gut, editorials target the mind, unraveling complex issues through structured reasoning. Both forms are political, but their methods and audiences differ sharply.

To craft an effective political cartoon, start with a clear message. Identify the issue, choose a recognizable figure or symbol, and exaggerate a key trait to highlight hypocrisy or absurdity. For instance, drawing a politician as a puppet controlled by corporate strings directly accuses them of being influenced by money. Use labels sparingly—the image should speak for itself. Contrast this with writing an editorial, where clarity and evidence are paramount. Begin with a hook—a startling fact or rhetorical question—then build your argument step by step. Cite data, historical parallels, or expert opinions to bolster your case. Conclude with a call to action or a provocative statement. While cartoons demand visual literacy, editorials require patience and critical thinking, making them better suited for audiences seeking in-depth analysis.

One key advantage of cartoons is their shareability. In the age of social media, a well-designed cartoon can go viral, reaching millions in minutes. Memes, essentially modern cartoons, often serve as political commentary, spreading ideas faster than any editorial. However, brevity can be a double-edged sword. Cartoons risk oversimplifying issues, reducing nuanced debates to black-and-white caricatures. Editorials, while slower to disseminate, provide the space to explore gray areas. For example, an editorial on climate policy can dissect economic impacts, scientific evidence, and political obstacles, offering readers a comprehensive understanding. To maximize impact, pair cartoons with short captions or accompanying text to bridge the gap between visual punch and analytical depth.

Despite their differences, cartoons and editorials share a common goal: to provoke thought and inspire action. Cartoons excel at emotional engagement, making them ideal for rallying public sentiment. Editorials, with their logical rigor, are better suited for influencing policymakers or educated audiences. For practitioners, the key is to know your audience. Are you aiming to mobilize the masses or sway the elite? Combine both forms strategically. A newspaper might run a cartoon alongside an editorial, using the image to draw readers in and the text to keep them thinking. In the battle of visual versus written commentary, there’s no winner—only complementary tools for shaping political discourse.

Are Political Conversations Worth the Effort? A Thoughtful Debate

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Punch's Influence on Public Opinion and Political Discourse

The satirical magazine *Punch*, which ran from 1841 to 2002, wielded significant influence over public opinion and political discourse in Britain. Its cartoons and articles served as a mirror to society, reflecting and shaping attitudes toward political figures, policies, and social issues. By blending humor with sharp critique, *Punch* became a powerful tool for both commentary and persuasion, often framing debates in ways that resonated with its middle-class readership. Its ability to distill complex political issues into accessible, entertaining content made it a formidable force in shaping public perception.

Consider the role of *Punch* during the Victorian era, when it tackled issues like electoral reform, imperialism, and social inequality. Its iconic cartoons, such as John Tenniel’s depictions of Prime Minister Disraeli and Gladstone, not only entertained but also reinforced or challenged prevailing narratives. For instance, *Punch* often portrayed Disraeli as a cunning manipulator, a characterization that subtly influenced how readers viewed his leadership. This demonstrates how visual satire could embed political biases into the public consciousness, often more effectively than written editorials. The magazine’s reach extended beyond its pages, as its cartoons were widely reproduced and discussed, amplifying its impact on political discourse.

To understand *Punch*’s influence, examine its strategy of using humor to disarm readers while delivering pointed critiques. This approach made controversial topics more palatable, encouraging readers to engage with ideas they might otherwise avoid. For example, during the suffragette movement, *Punch* initially mocked the demands for women’s rights, reflecting societal resistance. However, as public opinion shifted, so did the magazine’s tone, illustrating its responsiveness to—and influence on—changing attitudes. This adaptability allowed *Punch* to remain relevant while subtly guiding its audience’s views.

A practical takeaway for modern political commentators is to study *Punch*’s method of balancing entertainment with substance. Its success lay in its ability to make politics accessible without oversimplifying it. Today, creators of political satire can emulate this by pairing sharp wit with factual accuracy, ensuring their work informs as much as it amuses. For instance, incorporating historical context or data into satirical pieces can deepen their impact, much like *Punch*’s cartoons often included subtle references to current events. This approach not only engages audiences but also fosters a more informed public discourse.

Finally, *Punch*’s legacy underscores the enduring power of satire in shaping political narratives. By framing issues through humor, it could bypass the defenses of its audience, making critiques more palatable and memorable. However, this power came with responsibility, as *Punch*’s influence could reinforce biases as easily as it could challenge them. Modern satirists should heed this lesson, ensuring their work promotes critical thinking rather than merely reinforcing existing viewpoints. In an era of polarized politics, the *Punch* model offers a blueprint for satire that is both impactful and constructive.

Obama's Political Journey: A Timeline of His Public Service

You may want to see also

Evolution of Punch's Political Stance Over Time

The satirical magazine *Punch*, which ran from 1841 to 2002, mirrored the political tides of its time, evolving from a liberal voice to a more conservative one. In its early years, *Punch* championed reform, targeting the excesses of the British aristocracy and advocating for the working class. Its cartoons and articles skewered the establishment, particularly during the Victorian era, when it criticized the Corn Laws and supported parliamentary reform. This liberal stance was a product of its founding editors, who sought to use humor as a tool for social and political change.

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, *Punch* began to shift its political allegiance. The magazine’s tone grew more conservative, reflecting the anxieties of the British Empire’s decline and the rise of socialism. During World War I, it rallied behind the war effort, often portraying Germany as a caricatured villain. This patriotism extended into the interwar period, where *Punch* increasingly aligned with the establishment, mocking the Labour Party and left-wing ideologies. Its once-sharp critiques of the ruling class softened, replaced by a focus on maintaining traditional British values.

The post-World War II era marked another turning point for *Punch*. As Britain underwent significant social and political changes, the magazine struggled to find its footing. While it occasionally addressed issues like the welfare state and decolonization, its humor often felt out of touch with the zeitgeist. The 1960s and 1970s saw *Punch* attempt to modernize, but its conservative leanings remained evident, particularly in its skepticism of youth culture and progressive policies. This period highlighted the magazine’s inability to fully adapt to a rapidly changing political landscape.

In its final decades, *Punch* became a relic of a bygone era, its political stance increasingly irrelevant. The magazine’s decline mirrored the erosion of its conservative values in a society embracing multiculturalism and liberal ideals. Attempts to revive its relevance, such as hiring younger contributors, failed to recapture its former influence. *Punch*’s evolution from a liberal reformer to a conservative stalwart ultimately ended in obsolescence, a testament to the challenges of maintaining political relevance over time.

Understanding Political Addresses: Purpose, Structure, and Impact Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Punch shows, also known as Punch and Judy shows, were traditional puppet performances that originated in England. They featured slapstick humor and often included political satire, social commentary, and exaggerated characters.

Yes, punch shows often incorporated political themes and satire. They used humor to critique authority, social issues, and current events, making them a form of political commentary accessible to the public.

Punch shows addressed political topics through exaggerated characters, witty dialogue, and symbolic scenarios. They often mocked politicians, questioned societal norms, and reflected the concerns of the common people in a humorous and indirect manner.