Urban political machines, which dominated many American cities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, were complex and often controversial institutions. While they provided essential services, jobs, and support to immigrant communities, they were also criticized for corruption, patronage, and undemocratic practices. Labeling them as evil oversimplifies their role; they were a product of their time, addressing the needs of marginalized groups while exploiting systemic weaknesses for personal and political gain. Their legacy invites a nuanced examination of their impact on urban governance, social welfare, and the evolution of American politics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Corruption | Widespread graft, bribery, and embezzlement of public funds. |

| Patronage | Jobs and favors were given in exchange for political support. |

| Voter Fraud | Manipulation of elections through ballot stuffing, intimidation, and coercion. |

| Control of Local Government | Dominated city councils, police departments, and public services. |

| Boss-Centric Leadership | Power concentrated in the hands of a single "boss" or leader. |

| Clientelism | Networks of reciprocal obligations between politicians and constituents. |

| Lack of Transparency | Operations were often secretive and unaccountable to the public. |

| Exploitation of Immigrants | Used immigrants for votes and labor while offering limited benefits. |

| Monopoly on Power | Suppressed political opposition and maintained long-term control. |

| Public Works Projects | Built infrastructure but often for political gain rather than public good. |

| Social Services Provision | Provided basic services to the poor in exchange for loyalty. |

| Moral Ambiguity | Often viewed as both beneficial and harmful depending on perspective. |

| Decline in the 20th Century | Reforms and public outrage led to their gradual dismantling. |

| Historical Context | Prevalent in late 19th and early 20th century American cities. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Corruption and Graft: Bribery, embezzlement, and misuse of public funds by machine bosses and their allies

- Patronage Systems: Jobs and favors exchanged for political loyalty, creating dependency and control

- Voter Intimidation: Coercion, fraud, and manipulation to ensure machine-backed candidates won elections

- Social Services: Machines provided aid to immigrants and the poor, gaining support and loyalty

- Reform Movements: Efforts by progressives to dismantle machines, exposing their abuses and inefficiencies

Corruption and Graft: Bribery, embezzlement, and misuse of public funds by machine bosses and their allies

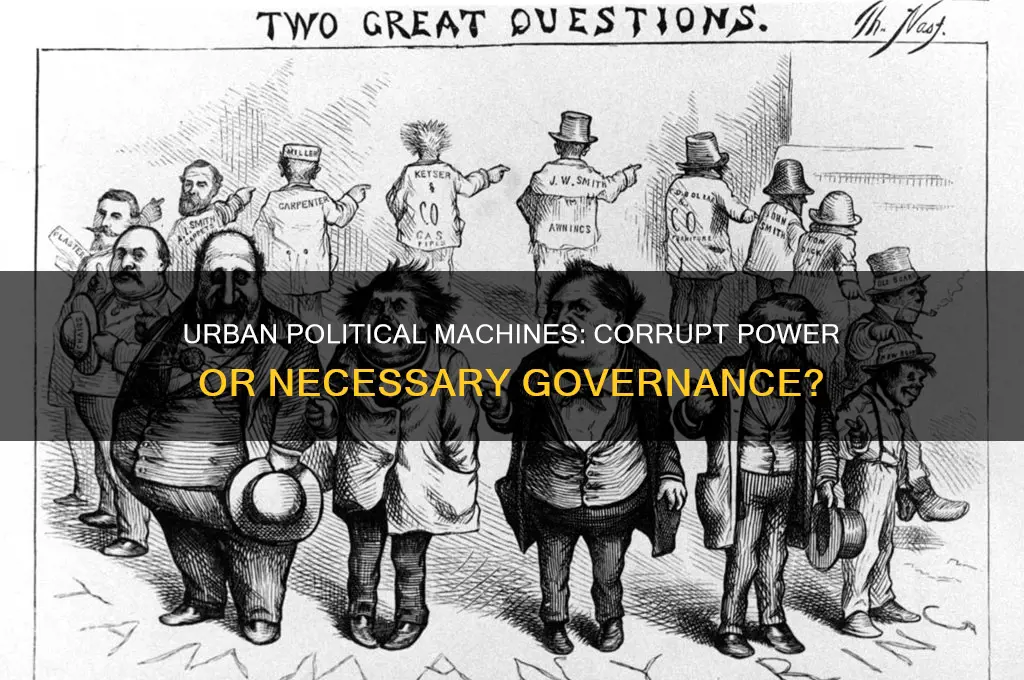

Urban political machines, often associated with late 19th and early 20th century American cities, were notorious for their systemic corruption and graft. At the heart of these operations were machine bosses who wielded immense power, often using it to line their pockets and those of their allies. Bribery was a cornerstone of their strategy, with public officials and private contractors exchanging cash or favors to secure lucrative government contracts. For instance, in Tammany Hall, the infamous Democratic machine in New York City, bosses like William "Boss" Tweed orchestrated schemes where contractors paid kickbacks to secure city construction projects, inflating costs and diverting funds meant for public good into private coffers.

Embezzlement further entrenched the machines' control, as bosses and their cronies siphoned public funds for personal gain. In Chicago, the machine led by Anton Cermak and later Richard J. Daley routinely manipulated city finances, using public money to reward loyalists and punish dissenters. A striking example is the 1919 Chicago Transit Authority scandal, where millions of dollars intended for public transportation improvements were embezzled, leaving the city’s infrastructure in disrepair while machine insiders profited. Such practices not only enriched the few but also undermined public trust in government institutions.

The misuse of public funds was another hallmark of machine politics, often disguised under the guise of "public works" or "community development." In Philadelphia, the machine led by John B. Kelly Sr. directed city funds toward projects that primarily benefited machine-aligned businesses and neighborhoods, neglecting areas that lacked political loyalty. This selective allocation of resources perpetuated inequality and stifled genuine economic growth. Similarly, in St. Louis, machine bosses funneled public funds into pet projects, such as parks and monuments, that served more as monuments to their power than as genuine public goods.

To combat such corruption, reformers in the early 20th century pushed for transparency and accountability measures, such as civil service reforms and direct primaries, which aimed to reduce the machines' stranglehold on patronage. However, the legacy of graft persists in modern politics, with echoes of machine-era tactics seen in contemporary lobbying and campaign finance abuses. For those seeking to understand or address corruption today, studying these historical examples offers valuable lessons: corruption thrives in systems lacking oversight, and dismantling it requires not just legal reforms but a cultural shift toward prioritizing the public good over private gain.

Understanding Political Geography: Territories, Power, and Global Dynamics Explained

You may want to see also

Patronage Systems: Jobs and favors exchanged for political loyalty, creating dependency and control

Patronage systems, the backbone of urban political machines, thrived on a simple yet powerful exchange: jobs and favors for unwavering political loyalty. This quid pro quo created a web of dependency, binding constituents to their political patrons through the basic need for employment and survival. Consider the Tammany Hall machine in 19th-century New York City, where immigrants, often excluded from mainstream economic opportunities, found jobs as sanitation workers, policemen, or clerks in exchange for their votes and support. This system wasn’t merely transactional; it was a lifeline, ensuring loyalty through necessity rather than ideology.

The mechanics of patronage systems reveal a calculated strategy of control. By monopolizing access to public sector jobs and resources, political bosses cultivated a loyal base that could be mobilized during elections or to counter opposition. For instance, in Chicago’s Democratic machine during the early 20th century, precinct captains distributed jobs, housing assistance, and even coal for winter heating, all contingent on residents’ political alignment. This dependency wasn’t accidental—it was engineered to ensure that the machine’s power remained unchallenged, even as it often perpetuated inefficiency and corruption.

Critics argue that patronage systems were inherently exploitative, preying on the vulnerabilities of marginalized communities. While these systems provided immediate relief, they stifled long-term economic mobility and fostered a culture of entitlement among political elites. For example, in Philadelphia’s Republican machine of the late 1800s, jobs were awarded based on loyalty rather than merit, leading to incompetence in public services. This raises a critical question: Were these systems a necessary evil in a rapidly industrializing, immigrant-heavy urban landscape, or were they a deliberate tool of oppression?

To dismantle patronage systems, reformers in the early 20th century pushed for civil service reforms, such as the Pendleton Act of 1883, which introduced merit-based hiring in federal jobs. However, the legacy of these systems persists in modern politics, where favoritism and cronyism still influence appointments and resource allocation. For those seeking to understand or combat such systems today, the key lies in transparency and accountability. Implementing strict oversight mechanisms, such as independent hiring committees and public audits, can disrupt the cycle of dependency and restore trust in public institutions.

Ultimately, patronage systems were neither wholly evil nor entirely benevolent—they were a reflection of the societal structures and power dynamics of their time. By examining their mechanisms and consequences, we gain insight into the delicate balance between political loyalty and public service. For communities still grappling with similar systems, the takeaway is clear: breaking the cycle of dependency requires not just reform but a fundamental shift toward equity and meritocracy.

Zelensky's Crackdown: Political Imprisonment or Legitimate Justice in Ukraine?

You may want to see also

Voter Intimidation: Coercion, fraud, and manipulation to ensure machine-backed candidates won elections

Urban political machines often relied on voter intimidation as a cornerstone of their electoral strategy, employing a mix of coercion, fraud, and manipulation to ensure their candidates’ victories. One common tactic was the use of "repeaters"—individuals paid to vote multiple times under different names. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, machines like Tammany Hall in New York City exploited lax voter registration systems, allowing these operatives to cast ballots in various precincts. This practice not only inflated vote counts but also demoralized opposition supporters, who felt their legitimate votes were drowned out by fraud.

Coercion took more direct forms, particularly in immigrant communities where machines held significant influence. Voters were often threatened with job loss, eviction, or the revocation of public services if they failed to support machine-backed candidates. For instance, in Chicago during the 1920s, the Democratic machine under Mayor William Hale Thompson pressured city workers to produce "signed and witnessed" ballots, effectively forcing them to vote in plain sight of machine operatives. Such tactics created an atmosphere of fear, silencing dissent and ensuring compliance through intimidation rather than persuasion.

Fraudulent practices extended beyond the ballot box, with machines manipulating voter rolls to their advantage. In cities like Philadelphia, machines would "pad" voter lists with fictitious names or deceased individuals, ensuring a steady supply of fraudulent votes. Additionally, ballot tampering was rampant, with machine operatives altering or destroying ballots to favor their candidates. The 1948 Senate election in Texas, for example, saw Lyndon B. Johnson’s campaign benefit from suspicious last-minute vote counts, a tactic often attributed to machine-style manipulation.

The psychological impact of these methods cannot be overstated. By controlling the electoral process through intimidation and fraud, machines undermined the very foundation of democratic participation. Voters, particularly those from marginalized communities, internalized the belief that their voices were irrelevant, fostering apathy and disengagement. This erosion of trust in the electoral system had long-term consequences, perpetuating machine dominance and stifling political competition.

To combat such practices, reforms like the introduction of secret ballots, stricter voter registration laws, and independent election monitoring became essential. The Australian ballot, adopted in the late 19th century, was a pivotal step in reducing coercion by ensuring voter privacy. Similarly, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 addressed systemic intimidation, particularly in the South, by empowering federal oversight. While these measures significantly curtailed machine tactics, the legacy of voter intimidation remains a cautionary tale about the fragility of democratic institutions.

Mormon Churches and Politics: Unraveling the Complex Relationship and Influence

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Social Services: Machines provided aid to immigrants and the poor, gaining support and loyalty

Urban political machines, often vilified for corruption and patronage, played a paradoxical role in providing social services to immigrants and the poor. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, these machines filled a void left by inadequate government welfare systems. For instance, Tammany Hall in New York City distributed coal to the needy during harsh winters, offered legal aid to immigrants navigating the complexities of American bureaucracy, and even provided jobs through patronage networks. These acts of charity were not purely altruistic; they were strategic investments in political loyalty. By meeting immediate needs, machines secured votes and created a dependent constituency, ensuring their continued dominance in urban politics.

Consider the mechanics of this system: a newly arrived immigrant family, struggling to find work and housing, would receive assistance from a machine-affiliated ward boss. This boss might provide a job, food, or even a small loan, all in exchange for a promise to vote for the machine’s candidates. Over time, this transactional relationship fostered a sense of obligation and gratitude, effectively tying the recipient’s fate to the machine’s political fortunes. Critics argue this was a form of exploitation, but for many marginalized groups, it was a lifeline in an otherwise indifferent society.

The effectiveness of this approach lies in its understanding of human psychology. By addressing tangible, immediate needs, machines created a personal connection with their constituents, something abstract political ideologies often failed to achieve. For example, during the 1890s, when unemployment soared in Chicago, the Democratic machine under Mayor John Hopkins organized public works projects, providing jobs to thousands. This not only alleviated economic hardship but also cemented the machine’s reputation as a protector of the working class. Such actions blurred the line between genuine social welfare and political manipulation, raising questions about the ethics of conditional aid.

However, the long-term consequences of this system were mixed. While machines provided essential services, their reliance on patronage and favoritism often perpetuated inequality. Jobs and resources were distributed based on loyalty rather than merit, stifling social mobility. Moreover, the dependency they fostered discouraged recipients from seeking systemic change, as their survival became tied to the machine’s continued power. This dynamic highlights a critical tension: were machines evil for exploiting vulnerability, or were they pragmatic actors filling a societal gap?

In evaluating this legacy, it’s instructive to compare it to modern social welfare systems. Today, governments and NGOs provide aid without explicit political strings attached, though influence and bias still exist. The machine model, while flawed, underscores the importance of addressing immediate needs as a foundation for broader social stability. For those designing contemporary aid programs, the lesson is clear: effective support must be both practical and sustainable, avoiding the pitfalls of dependency while fostering genuine empowerment.

Joe Biden's Enduring Political Career: A Timeline of Service

You may want to see also

Reform Movements: Efforts by progressives to dismantle machines, exposing their abuses and inefficiencies

Urban political machines, often criticized for their corruption and inefficiency, became prime targets for reform movements in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Progressives, armed with a vision of good governance and social justice, launched concerted efforts to dismantle these machines, exposing their abuses and inefficiencies. Their strategies were multifaceted, combining investigative journalism, legislative reform, and grassroots mobilization to challenge the entrenched power of machine politics. By shining a light on the backroom deals, voter fraud, and patronage systems that sustained these machines, reformers sought to restore accountability and transparency to urban governance.

One of the most effective tools in the reformers’ arsenal was investigative journalism, often referred to as muckraking. Journalists like Lincoln Steffens and Jacob Riis exposed the inner workings of political machines, detailing how they exploited the poor, manipulated elections, and siphoned public funds for private gain. Steffens’ *The Shame of the Cities* (1904) became a rallying cry, documenting corruption in cities like St. Louis and Philadelphia. These exposés galvanized public opinion, making it harder for machine bosses to operate in the shadows. Reformers also leveraged this public outrage to push for structural changes, such as the introduction of nonpartisan elections and civil service reforms, which aimed to replace patronage with merit-based hiring.

Legislative reforms played a critical role in dismantling political machines. Progressives championed initiatives like the direct primary system, which allowed voters to choose candidates without machine interference, and the secret ballot, which reduced voter intimidation and bribery. In cities like New York and Chicago, reformers pushed for the adoption of city manager systems, shifting power from corrupt aldermen to professional administrators. These measures, while not always successful, disrupted the machines’ control over local politics and laid the groundwork for more accountable governance. However, reformers faced stiff resistance, as machine bosses often used their influence to block or dilute these reforms.

Grassroots movements were equally vital in the fight against political machines. Organizations like the National Municipal League and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union mobilized citizens to demand ethical leadership and efficient public services. In Milwaukee, for instance, the “sewer socialists” led by Emil Seidel and Daniel Hoan demonstrated how progressive governance could improve urban life, offering a stark contrast to machine-dominated cities. These movements emphasized civic engagement, encouraging citizens to participate in local elections and hold their leaders accountable. By fostering a culture of transparency and activism, they chipped away at the machines’ power base.

Despite their successes, reform movements faced significant challenges. Political machines were deeply entrenched, often enjoying the support of immigrant communities who relied on them for jobs and services. Reformers sometimes struggled to balance their ideals with the practical needs of these communities, leading to accusations of elitism. Additionally, the machines’ adaptability allowed them to survive in various forms, even as direct control waned. Yet, the legacy of these reform efforts endures in modern governance structures, from civil service protections to campaign finance regulations. They remind us that the fight against corruption and inefficiency is ongoing, requiring vigilance and sustained effort.

Barriers to Democracy: Understanding Factors Discouraging Political Participation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Urban political machines were not inherently evil but were often criticized for corruption, patronage, and prioritizing political power over public good. They provided essential services to immigrants and the poor but sometimes exploited these communities for votes.

While urban political machines often enriched the politicians and their allies, they also provided jobs, social services, and support to marginalized groups. However, these benefits were frequently tied to political loyalty, creating a system of dependency.

Many argue that urban political machines were a necessary response to the failures of government to address the needs of rapidly growing, diverse urban populations. While they had flaws, they filled a void in social welfare and political representation during a time of significant change.