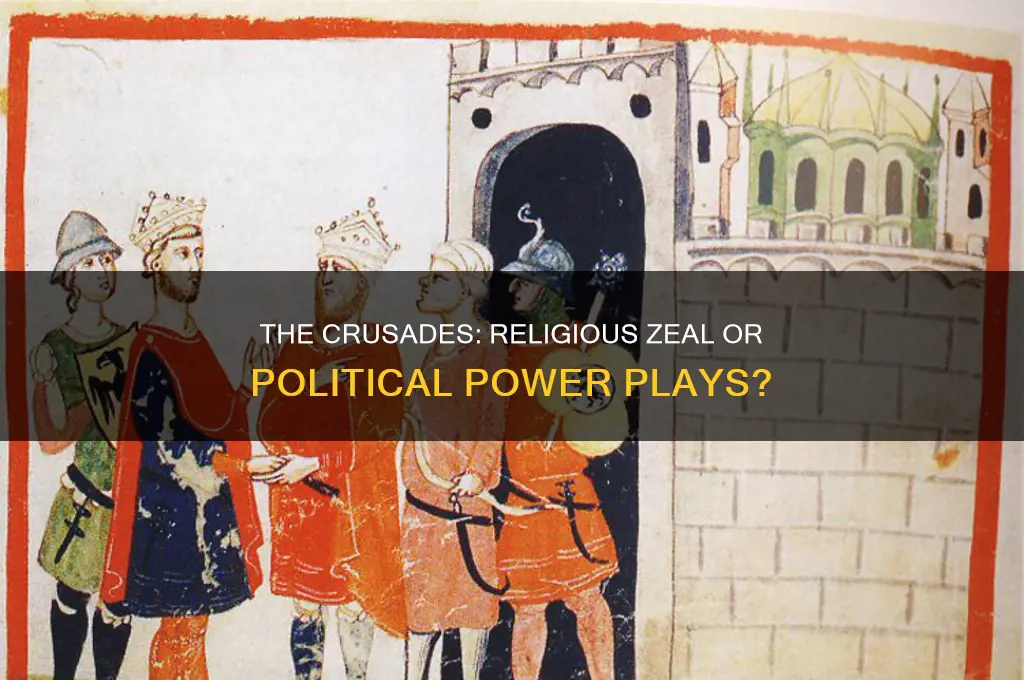

The question of whether the Crusades were primarily political in nature is a complex and multifaceted one, as these religious wars between Christians and Muslims from the 11th to the 13th centuries were driven by a myriad of factors, including religious zeal, economic gain, and territorial expansion. While the Crusades were ostensibly launched as a means of reclaiming the Holy Land from Muslim control and protecting Christian pilgrims, many historians argue that they were also motivated by political ambitions, such as the desire of European monarchs and nobles to consolidate power, expand their territories, and forge alliances through marriage and military campaigns. The involvement of the Papacy, which sought to assert its authority over secular rulers and unify Christendom, further complicates the narrative, as religious and political objectives often became intertwined, making it difficult to disentangle the true driving forces behind these protracted and devastating conflicts. As such, understanding the political dimensions of the Crusades requires a nuanced examination of the interplay between religion, power, and identity in medieval Europe and the Middle East.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Motivations | Mixed religious and political goals; expansion of influence, wealth, and territory alongside religious zeal. |

| Papal Involvement | Popes initiated and directed Crusades for religious and political purposes (e.g., strengthening papal authority). |

| Feudal Politics | Nobles participated to gain land, resolve internal conflicts, or secure alliances. |

| Economic Interests | Control of trade routes, access to resources, and economic exploitation of conquered regions. |

| Dynastic Ambitions | Rulers used Crusades to solidify power, legitimize rule, or expand dynasties (e.g., the Angevin Empire). |

| Religious Justification | Political actions were often framed as religious duties to reclaim holy lands or combat heresy. |

| Colonial Expansion | Establishment of Crusader states (e.g., Kingdom of Jerusalem) as political and economic outposts. |

| Cultural Exchange | Political interactions led to cultural and technological exchanges between Europe and the Middle East. |

| Military Orders | Orders like the Templars and Hospitallers served both religious and political-military functions. |

| Legacy of Conflict | Long-term political rivalries and tensions between Christian and Muslim powers shaped by Crusade dynamics. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Papal Authority vs. Secular Power: Examines how the Pope's influence intersected with kings' ambitions during the Crusades

- Feudal Politics and Alliances: Explores how feudal lords used the Crusades to strengthen or shift alliances

- Economic Motivations: Investigates the role of trade, wealth, and resource control in driving Crusade participation

- Territorial Expansion: Analyzes how European powers sought to expand their territories under the guise of religion

- Rivalries Between Kingdoms: Highlights how competition among kingdoms influenced Crusade strategies and outcomes

Papal Authority vs. Secular Power: Examines how the Pope's influence intersected with kings' ambitions during the Crusades

The Crusades, often portrayed as purely religious endeavors, were in fact deeply intertwined with the political ambitions of both papal and secular leaders. The Popes, wielding spiritual authority, sought to expand the influence of the Church, while kings and nobles saw the Crusades as opportunities to consolidate power, gain wealth, and secure political legitimacy. This dynamic tension between papal authority and secular power shaped the course of the Crusades, often leading to conflicts and alliances that transcended religious goals.

Consider the First Crusade, launched by Pope Urban II in 1095. While the Pope framed it as a holy war to reclaim the Holy Land, secular rulers like Godfrey of Bouillon and Bohemond of Taranto had their own motives. For Godfrey, the Crusade offered a chance to elevate his status from a lesser noble to a leader of Christendom, eventually becoming the first ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Bohemond, on the other hand, sought to expand his territories in the Byzantine Empire, using the Crusade as a pretext for conquest. These examples illustrate how the Popes’ call to arms was often a catalyst for secular leaders to pursue their own political agendas.

The interplay between papal and secular power was not always adversarial. During the Third Crusade, Pope Innocent III and Emperor Frederick Barbarossa formed an uneasy alliance, despite their ongoing disputes over the investiture controversy. Innocent III needed Frederick’s military might to succeed in the Crusade, while Frederick sought papal recognition to strengthen his claim to the Holy Roman Empire. This pragmatic collaboration highlights how both parties could temporarily set aside their differences when their interests aligned. However, such alliances were often fragile, as the underlying tensions between spiritual and temporal authority persisted.

One of the most striking examples of this conflict occurred during the Fourth Crusade, when Pope Innocent III’s call for a holy war was hijacked by Venetian merchants and secular leaders. Instead of marching on Jerusalem, the Crusaders sacked the Christian city of Constantinople, establishing the Latin Empire in 1204. This diversion, driven by the political and economic ambitions of Venice and the Crusaders, directly contradicted papal intentions. Innocent III excommunicated the participants, but the damage was done, revealing the limits of papal control over secular actions in the Crusades.

To navigate this complex relationship, modern scholars and historians can draw practical lessons. First, analyze primary sources critically to uncover the hidden motives of both papal and secular leaders. Second, map the political landscapes of the time, identifying key players and their ambitions. Finally, consider the long-term consequences of these intersections, such as the rise of nation-states and the decline of papal authority in Europe. By doing so, we gain a nuanced understanding of how the Crusades were not just religious wars but also arenas for the struggle between papal authority and secular power.

Mastering the Art of Polite Borrowing: Tips for Gracious Requests

You may want to see also

Feudal Politics and Alliances: Explores how feudal lords used the Crusades to strengthen or shift alliances

The Crusades, often romanticized as purely religious endeavors, were deeply intertwined with the political machinations of feudal Europe. Feudal lords, ever vigilant in their pursuit of power and influence, leveraged these holy wars to forge, strengthen, or sever alliances. By aligning themselves with the Crusades, they could consolidate their authority, expand their territories, and neutralize rivals under the guise of divine sanction. This strategic use of religious fervor transformed the Crusades into a tool for political maneuvering, where the cross was as much a symbol of ambition as it was of faith.

Consider the First Crusade, launched in 1095, as a prime example. Lords like Godfrey of Bouillon and Hugh of Vermandois did not merely answer Pope Urban II’s call out of piety; they saw an opportunity to elevate their status. By leading armies to the Holy Land, they gained prestige, legitimized their rule, and formed alliances with other nobles who shared their ambitions. These alliances were not just military but also dynastic, as marriages and treaties were brokered to solidify newfound partnerships. For instance, the marriage of Baldwin of Boulogne to Arda of Armenia was a political union that secured territorial claims and strengthened alliances in the Levant.

However, the Crusades were not always a unifying force. Feudal politics often turned them into arenas of rivalry and betrayal. Lords who competed for resources, land, or influence in Europe carried their feuds to the Holy Land, undermining the very cause they claimed to champion. The Fourth Crusade, which infamously sacked Constantinople in 1204, exemplifies this. Venetian Doge Enrico Dandolo and other leaders diverted the Crusade to serve their political and economic interests, demonstrating how alliances could be manipulated or broken for personal gain. This shift from religious to political objectives highlights the dual nature of the Crusades as both a spiritual and a strategic endeavor.

To understand the mechanics of these alliances, one must examine the feudal system itself. Lords owed service to their overlords, but the Crusades provided a loophole. By participating in a holy war, a lord could temporarily escape feudal obligations, allowing them to act more independently. This autonomy enabled them to form new alliances or renegotiate existing ones. For instance, a lesser lord might align with a more powerful neighbor to gain protection or resources, using the Crusade as a pretext to shift loyalties without incurring retribution. This fluidity in alliances reflects the dynamic and often opportunistic nature of feudal politics during the Crusades.

In practical terms, feudal lords employed several strategies to maximize their political gains. First, they used the Crusades to eliminate domestic rivals by sending them on perilous journeys from which they might not return. Second, they exploited the financial and logistical demands of the Crusades to consolidate wealth and power, often at the expense of their vassals or peasants. Finally, they leveraged the moral authority of the Church to legitimize their actions, ensuring that their political maneuvers were perceived as righteous. These tactics reveal the calculated way in which feudal lords manipulated the Crusades to serve their own interests.

In conclusion, the Crusades were not merely religious expeditions but also complex political events shaped by the ambitions of feudal lords. By using these holy wars to strengthen or shift alliances, they navigated the intricate web of medieval power dynamics. The interplay between faith and politics during the Crusades underscores the multifaceted nature of this era, where the sacred and the secular were inextricably linked. Understanding this dynamic offers valuable insights into the motivations and strategies of those who shaped the course of history.

Is Harvard Political Review Reliable? Evaluating Credibility and Bias

You may want to see also

Economic Motivations: Investigates the role of trade, wealth, and resource control in driving Crusade participation

The Crusades, often portrayed as purely religious endeavors, were significantly driven by economic motivations that intertwined with political and social factors. One of the most compelling examples is the control of trade routes, particularly those connecting Europe to the wealthy markets of the East. By the 11th century, European economies were expanding, and access to spices, silk, and other luxury goods from Asia became a critical source of wealth. The Seljuk Turks’ control of key trade routes through the Holy Land threatened this economic lifeline, prompting European powers to seek dominance over these pathways under the guise of religious liberation.

Consider the Venetian and Genoese republics, whose participation in the Crusades was as much about securing trade monopolies as it was about religious fervor. These maritime powers funded and transported Crusaders in exchange for commercial privileges in captured territories. For instance, the Fourth Crusade’s diversion to Constantinople in 1204 was partly motivated by Venice’s desire to weaken its Byzantine trade rival. The Crusaders’ sack of the city redistributed wealth and resources, benefiting Western merchants who gained access to Eastern markets previously controlled by Byzantine intermediaries.

Resource control also played a pivotal role in Crusade participation. The Holy Land was not only a spiritual destination but also a region rich in agricultural and mineral resources. Knights and nobles, often burdened by debt or seeking to expand their estates, saw the Crusades as an opportunity to acquire land and resources. The establishment of Crusader states like the Kingdom of Jerusalem provided new territories for exploitation, with European settlers imposing feudal systems to extract wealth from the local population. This economic colonization mirrored the political ambitions of European powers to project their influence abroad.

However, the economic motivations behind the Crusades were not without risk. The high cost of equipping and transporting armies often led to financial strain, with monarchs and nobles taxing their populations heavily or borrowing from wealthy financiers. The Knights Templar, initially founded as a military order, evolved into a powerful banking institution, managing the finances of Crusaders and even issuing letters of credit. Their economic influence highlights how financial systems were adapted to support the Crusades, further underscoring the interplay between wealth and warfare.

In conclusion, the Crusades were not merely religious wars but complex campaigns driven by economic ambitions. Trade, wealth, and resource control were central to the participation of individuals and states alike. By examining these motivations, we gain a clearer understanding of how economic interests shaped political and military strategies during this pivotal period in history. The legacy of these economic endeavors continues to inform our analysis of how religion and commerce have historically intersected to drive global conflicts.

Are We Too Politically Sensitive? Examining Our Generation's Hyperawareness

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Territorial Expansion: Analyzes how European powers sought to expand their territories under the guise of religion

The Crusades, often portrayed as purely religious endeavors, were in fact vehicles for territorial expansion, cloaked in the rhetoric of faith. European powers, particularly during the 11th to 13th centuries, leveraged the religious fervor of the time to justify military campaigns that ultimately served their geopolitical ambitions. The First Crusade, for instance, resulted in the establishment of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and other Crusader states, territories that were not only religiously significant but also strategically located for trade and influence in the Eastern Mediterranean. This pattern of expansion under the guise of religion set a precedent for future campaigns, where the cross and the sword became inseparable tools of statecraft.

Consider the Fourth Crusade, a stark example of how religious zeal was manipulated for political gain. Originally intended to reclaim Jerusalem, the Crusade was diverted to Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, a fellow Christian state. The Crusaders, influenced by Venetian interests, sacked the city in 1204, carving out territories that benefited Western European powers. This act of aggression against a Christian empire highlights how the Crusades were often less about religious purity and more about securing land, resources, and trade routes. The veneer of piety masked the raw pursuit of power and wealth.

To understand the mechanics of this expansion, examine the role of feudal lords and monarchs who led these campaigns. Figures like Richard the Lionheart and Frederick Barbarossa were not merely devout warriors but also shrewd politicians. They mobilized their vassals and subjects by appealing to religious duty, while simultaneously advancing their own territorial claims. For example, the establishment of military orders like the Knights Templar and the Hospitallers served dual purposes: defending the Holy Land and consolidating European control over newly acquired lands. These orders became de facto colonial administrators, enforcing European authority in the East.

A comparative analysis of the Crusades with other historical expansions reveals a recurring theme: the use of ideology to legitimize conquest. Just as colonial powers in later centuries justified their actions through the "civilizing mission," the Crusaders framed their campaigns as a divine mandate. However, the outcomes were often indistinguishable from secular conquests. Cities like Acre and Antioch became hubs of European trade, and the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem was governed by a feudal system imported from the West. Religion provided the moral cover, but the ultimate goal was the extension of European influence and control.

In practical terms, the legacy of this territorial expansion is still evident today. The Crusades reshaped the political and cultural landscape of the Mediterranean and the Middle East, leaving a complex interplay of religious and political identities. For modern policymakers and historians, understanding this dynamic is crucial. It underscores the dangers of conflating religious and political objectives and serves as a cautionary tale about the long-term consequences of such actions. By dissecting the Crusades through the lens of territorial expansion, we gain insights into how ideology can be weaponized to achieve geopolitical ends, a lesson as relevant now as it was in the medieval period.

Polite or Rude: Navigating Social Etiquette and Respectful Communication

You may want to see also

Rivalries Between Kingdoms: Highlights how competition among kingdoms influenced Crusade strategies and outcomes

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) stands as a stark example of how rivalries between kingdoms could hijack the stated religious goals of the Crusades. Initially aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem, the Crusade was diverted to Constantinople due to a complex web of political debts and alliances. The Doge of Venice, Enrico Dandolo, leveraged the Crusaders’ financial dependence on his fleet to redirect their efforts against the Byzantine Empire, a rival of Venice. This diversion not only undermined the Crusade’s religious purpose but also resulted in the sack of Constantinople, a Christian city, and the weakening of the Byzantine Empire, which had long served as a buffer against Muslim expansion. This case illustrates how inter-kingdom competition could distort Crusade strategies, prioritizing political and economic gains over religious objectives.

Consider the rivalry between the Angevin Empire and the Kingdom of France during the Third Crusade (1189–1192). Richard I of England (the Lionheart) and Philip II of France, nominal allies, were locked in a power struggle that overshadowed their collaboration against Saladin. Richard’s focus on securing his own territories and Philip’s early departure from the Crusade highlight how personal and dynastic rivalries could fracture unity. Their competition for dominance within the Crusader ranks not only weakened the overall effort but also led to suboptimal military decisions, such as the prolonged siege of Acre. This rivalry demonstrates how kingdoms’ self-interest could undermine the collective goals of the Crusades, turning them into extensions of existing conflicts rather than unified religious endeavors.

To understand the impact of kingdom rivalries on Crusade outcomes, examine the role of the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy during the Crusades. The Emperors, such as Frederick Barbarossa, often clashed with the Popes over authority and resources, which affected their commitment to the Crusades. For instance, Frederick’s untimely death during the Third Crusade deprived the Crusaders of a critical leader, partly due to the strained relationship between the Empire and the Papacy. This rivalry not only hindered logistical support but also created divisions among Crusader forces, as different factions aligned with either the Emperor or the Pope. Practical tip: When analyzing Crusade histories, trace the correspondence between kings and popes to uncover how political rivalries influenced troop movements, funding, and strategic decisions.

A comparative analysis of the First and Second Crusades reveals how shifting alliances and rivalries altered their trajectories. The First Crusade (1095–1099) succeeded in capturing Jerusalem due to relative unity among Western kingdoms, driven by a shared religious fervor and papal authority. In contrast, the Second Crusade (1147–1149) failed spectacularly, partly because of rivalries between Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany, who struggled to coordinate their forces effectively. This comparison underscores how the absence or presence of inter-kingdom competition could make or break a Crusade. Takeaway: Rivalries between kingdoms were not mere background noise but active forces that shaped the strategies, execution, and outcomes of the Crusades, often at the expense of their religious mission.

Understanding the Dynamics of a Political Learning Environment

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

While religious zeal was a significant driving force, the Crusades were also deeply intertwined with political ambitions. European monarchs and nobles sought to expand their influence, gain wealth, and consolidate power through participation in the Crusades, often using religious rhetoric to justify their actions.

Yes, political rivalries played a crucial role. For example, the Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was diverted to sack the Christian city of Constantinople due to political and economic interests of Venetian leaders, demonstrating how political agendas often overshadowed religious goals.

In some cases, yes. Rulers like Pope Urban II and later monarchs encouraged the Crusades to redirect the energies of restless knights and peasants, reducing internal conflicts and unifying populations under a common cause.

Absolutely. While the Crusades were launched to reclaim the Holy Land for Christianity, their political outcomes included the establishment of trade routes, the rise of powerful military orders, and the weakening of the Byzantine Empire, which had long-term geopolitical consequences beyond religious aims.