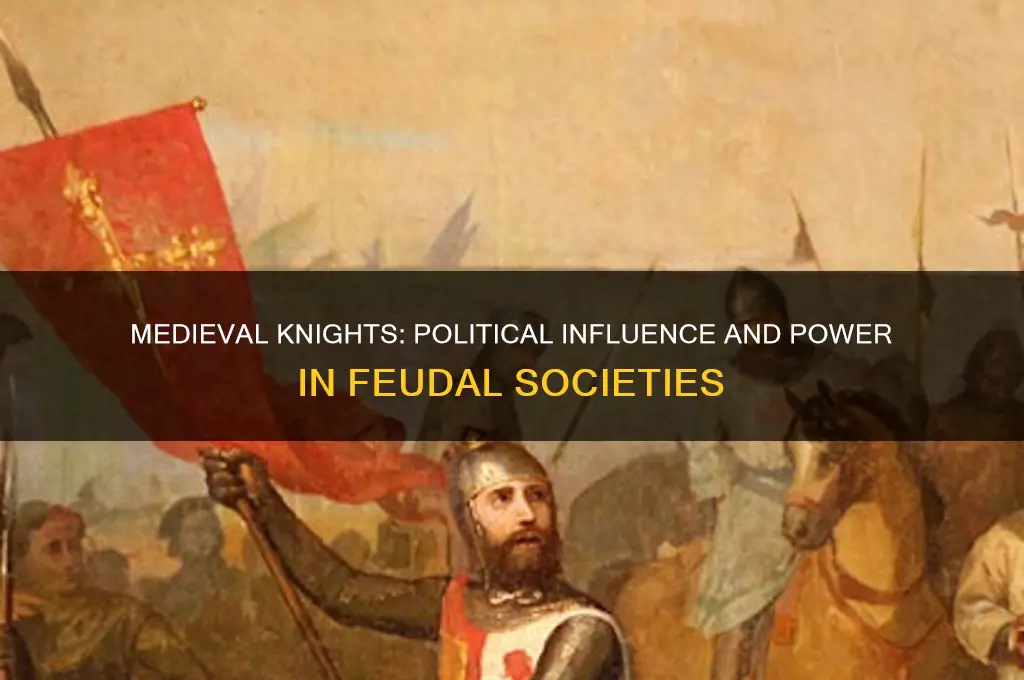

Medieval knights, often romanticized as chivalrous warriors, played a multifaceted role in the political landscape of their time. Beyond their martial duties, knights were deeply embedded in the feudal system, serving as vassals to lords and often holding significant influence in local governance. Their political activity ranged from participating in councils and parliaments to acting as advisors, administrators, and even diplomats. Knights frequently mediated disputes, enforced laws, and represented their lords’ interests, making them key intermediaries between the nobility and the common populace. Additionally, their military prowess often translated into political leverage, as they could sway decisions through their ability to mobilize forces. Thus, while their primary image is that of combatants, medieval knights were indeed politically active, shaping the social and governmental structures of their era.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Roles | Knights often held positions of authority, such as castellans, sheriffs, or members of royal councils, directly influencing local and regional governance. |

| Feudal Obligations | As vassals, knights were politically active through their loyalty and service to lords, participating in decision-making and administration within feudal hierarchies. |

| Military Leadership | Knights led armies and defended territories, which often involved political negotiations, alliances, and strategic decisions affecting regional stability. |

| Parliamentary Participation | In emerging parliamentary systems (e.g., England's Magna Carta era), knights represented counties or shires, shaping laws and policies. |

| Diplomatic Missions | Knights were frequently sent as envoys to negotiate treaties, alliances, or resolve disputes between kingdoms or noble houses. |

| Local Governance | Many knights managed estates, collected taxes, and administered justice in their domains, acting as de facto local rulers. |

| Patronage and Influence | Wealthy knights patronized churches, towns, and cultural institutions, leveraging their influence to shape political and social landscapes. |

| Rebellions and Factions | Knights often participated in or led rebellions against monarchs or rival lords, demonstrating their political agency and ambition. |

| Court Influence | Knights close to monarchs or nobles wielded significant political power through personal relationships and court intrigue. |

| Legal Authority | Knights served as judges in local courts, enforcing laws and resolving disputes, which reinforced their political role in society. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Knights' role in feudal governance

Medieval knights were integral to the fabric of feudal governance, serving as both enforcers and administrators in a system built on hierarchy and obligation. Their role extended beyond the battlefield, as they often acted as intermediaries between lords and peasants, ensuring the smooth operation of manorial estates. Knights were granted fiefs—portions of land—in exchange for military service and loyalty, which positioned them as local authorities with significant influence over the lives of those under their jurisdiction. This dual role as warriors and governors made them indispensable to the feudal order.

Consider the practical responsibilities of a knight in governance. They oversaw the collection of taxes, resolved disputes among peasants, and maintained law and order within their fief. For instance, a knight might adjudicate a land dispute between two farmers, relying on local customs and the lord’s directives to render a fair judgment. This administrative function required not only physical prowess but also a degree of diplomacy and understanding of feudal law. Knights who excelled in these duties often gained greater favor with their lords, leading to increased power and prestige.

However, the political activity of knights was not without its limitations. Their authority was derived from and ultimately subordinate to their lord’s will. A knight’s decisions could be overturned if they contradicted the lord’s interests, and their tenure over a fief was contingent on continued service and loyalty. This dynamic highlights the delicate balance knights had to maintain: asserting authority while remaining obedient to their superiors. Failure to navigate this balance could result in the loss of land, status, and even life.

To understand the broader impact of knights on feudal governance, examine their role in regional and national politics. Knights often served as advisors to their lords, participating in councils and contributing to strategic decisions. During times of crisis, such as succession disputes or external threats, their counsel and military expertise were invaluable. For example, the Magna Carta of 1215, which limited the power of the English monarch, was influenced by the collective demands of barons and their knights, demonstrating their ability to shape political outcomes.

In conclusion, knights were not merely warriors but active participants in the governance of feudal society. Their roles as administrators, judges, and advisors underscore their political significance, though their authority was always framed within the constraints of feudal hierarchy. By examining their duties and influence, we gain a clearer picture of how knights contributed to the stability and evolution of medieval political structures. Their legacy endures as a testament to the multifaceted nature of power in the feudal era.

Demography's Role in Shaping Political Landscapes: Destiny or Coincidence?

You may want to see also

Political alliances through knightly marriages

Medieval knights were not merely warriors; they were pivotal figures in the political landscape of their time. One of the most strategic ways they exerted influence was through marriage alliances. These unions were carefully orchestrated to forge bonds between noble families, consolidate power, and secure territorial claims. By marrying their daughters, sisters, or even themselves into rival or neighboring houses, knights and their lords could neutralize threats, gain access to resources, and expand their spheres of influence. Such marriages were less about romance and more about realpolitik, serving as a cornerstone of medieval diplomacy.

Consider the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine, a prime example of how knightly and noble marriages shaped political landscapes. Eleanor’s first marriage to King Louis VII of France brought her vast lands in southwestern France under the French crown, strengthening its southern frontier. However, her subsequent marriage to Henry II of England, after her annulment from Louis, shifted those same territories into English hands, setting the stage for centuries of Anglo-French conflict. This illustrates how a single marriage could dramatically alter the balance of power in medieval Europe, with knights often acting as the enforcers and beneficiaries of such alliances.

To understand the mechanics of these alliances, imagine a chessboard where each piece represents a noble family or knight. Marriages were the moves that aligned interests, protected vulnerabilities, and advanced strategic goals. For instance, a knight from a lesser house might marry the daughter of a more powerful lord, gaining protection and patronage in exchange for military service. Conversely, a lord might marry his daughter to a rival’s son to end a feud or secure a truce. These unions were often sealed with dowries of land, wealth, or military support, further intertwining the fates of the families involved.

However, these alliances were not without risks. Marriages could backfire if loyalties shifted, heirs failed to materialize, or conflicts arose between the allied houses. The Wars of the Roses in England, for example, were partly fueled by competing marriage alliances and claims to the throne. Knights caught in such disputes often had to choose between their familial obligations and their feudal loyalties, highlighting the precarious nature of these political unions.

In practice, forging a successful marriage alliance required careful negotiation, often involving intermediaries like clergy or trusted advisors. Families would scrutinize potential partners for their lineage, wealth, and political standing. Once a match was agreed upon, the wedding itself became a public display of unity, with feasts, tournaments, and other celebrations reinforcing the new bond. Knights played a dual role in these events, both as participants in the festivities and as guarantors of the alliance’s enforcement.

In conclusion, political alliances through knightly marriages were a sophisticated tool of medieval statecraft. They allowed knights and their lords to navigate the complex web of power dynamics, secure their positions, and shape the course of history. By examining these unions, we gain insight into the intricate interplay between personal relationships and political strategy in the medieval world. For anyone studying this period, understanding these marriages is essential to grasping the broader dynamics of power and loyalty in the Middle Ages.

Understanding Bipolar Politics: Polarization, Division, and Its Global Impact

You may want to see also

Knights as advisors to monarchs

Medieval knights were not merely warriors on the battlefield; they often served as trusted advisors to monarchs, shaping political decisions that influenced the course of kingdoms. This role was particularly prominent during the feudal system, where knights, as vassals, owed loyalty and service to their lords, who were often kings or queens. Their proximity to power and firsthand experience in matters of war, diplomacy, and governance made them invaluable counselors. For instance, William Marshal, known as "the greatest knight," served four English kings, offering strategic advice that stabilized the throne during turbulent times. His influence extended beyond military tactics to matters of statecraft, illustrating how knights could wield significant political power.

To understand the mechanics of this advisory role, consider the structure of medieval courts. Knights were often part of the royal household, attending council meetings and providing insights on issues ranging from territorial disputes to alliances. Their advice was grounded in practical experience, whether it was assessing the strength of enemy forces or negotiating with foreign powers. For example, during the Crusades, knights like Godfrey of Bouillon not only led armies but also advised monarchs on the political complexities of the Holy Land. This dual role as warrior and advisor highlights the multifaceted nature of knighthood, where martial skill was complemented by political acumen.

However, the influence of knights as advisors was not without limitations. Their counsel was often shaped by personal interests, such as expanding their own lands or protecting their families' legacies. This could lead to conflicts of interest, as seen in the Wars of the Roses, where knights aligned with rival factions, undermining royal authority. Monarchs, aware of these dynamics, frequently balanced the advice of knights with that of clergy, bureaucrats, and other nobles. Thus, while knights were pivotal advisors, their political role was part of a larger, intricate web of influence.

Practical tips for understanding this historical dynamic include studying primary sources like chronicles and letters, which often detail the interactions between knights and monarchs. For instance, the *Chronicles of Jean Froissart* provide vivid accounts of knights advising kings during the Hundred Years' War. Additionally, examining the administrative records of medieval courts can reveal how knights' advice was implemented in policy decisions. By combining these sources with modern historical analysis, one can gain a nuanced understanding of how knights shaped medieval politics from the throne room, not just the battlefield.

Understanding the Dynamics of a Political Learning Environment

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Rebellion and resistance led by knights

Medieval knights were not merely symbols of chivalry and martial prowess; they were also key actors in political rebellion and resistance. Their privileged position as landowners and military leaders often placed them at the forefront of opposition to royal or feudal authority. One of the most striking examples is the Revolt of the Barons in 12th-century England, where knights like Simon de Montfort led a coalition against King John, culminating in the Magna Carta—a foundational document for constitutional governance. This rebellion underscores how knights leveraged their military and social standing to challenge the crown, often in the name of limiting arbitrary power.

To understand the mechanics of knight-led resistance, consider their unique role as intermediaries between the nobility and the common populace. Knights frequently organized and mobilized local forces, drawing on their feudal networks to rally support. For instance, during the Jacquerie uprising in 14th-century France, knights like Charles II of Navarre exploited peasant discontent to further their own political ambitions. While this example highlights the potential for knights to manipulate resistance movements, it also demonstrates their ability to act as both leaders and opportunists in times of rebellion.

A persuasive argument can be made that knight-led rebellions were often driven by a mix of personal ambition and ideological conviction. Knights like William Wallace in Scotland or Owain Glyndŵr in Wales framed their resistance as a fight for national or regional autonomy, tapping into broader sentiments of identity and freedom. These figures were not merely rebels but also symbols of defiance against foreign or centralized rule. Their actions remind us that political resistance in the medieval period was rarely apolitical; it was deeply intertwined with questions of loyalty, legitimacy, and power.

Practical lessons from these historical rebellions can inform modern understandings of political resistance. Knights succeeded when they combined military strategy with political acumen, often forming alliances across social classes or exploiting divisions within the ruling elite. For instance, the Hundred Years' War saw knights like Joan of Arc unite disparate factions under a common cause. To emulate their effectiveness, modern resistance movements might focus on building broad coalitions, leveraging symbolic leadership, and framing their struggles in terms of shared values. However, caution must be exercised: knights’ reliance on feudal structures and personal charisma also limited the sustainability of their rebellions, a reminder that leadership alone is insufficient without institutional support.

In conclusion, rebellion and resistance led by knights were not isolated incidents but recurring features of medieval politics. Their actions reveal the complex interplay between personal ambition, ideological conviction, and structural power dynamics. By studying these examples, we gain insights into the strategies and limitations of political resistance, offering both inspiration and cautionary tales for contemporary movements. Knights were not just warriors; they were political actors whose legacies continue to shape our understanding of power and rebellion.

Understanding Independent Politics: A Guide to Non-Partisan Political Stance

You may want to see also

Influence on medieval parliamentary systems

Medieval knights were not merely warriors; they were pivotal in shaping the early parliamentary systems of Europe. Their political influence stemmed from their dual role as landowners and military elites, which granted them significant local authority. In England, for example, knights of the shire were elected to represent their counties in the House of Commons by the 13th century, marking a shift from feudal obligations to structured political participation. This evolution underscores how knightly involvement laid the groundwork for representative governance.

Consider the practical mechanics of their influence. Knights often acted as intermediaries between the monarchy and local communities, leveraging their prestige to negotiate taxes, resolve disputes, and enforce royal decrees. Their presence in parliamentary bodies ensured that regional interests were voiced, balancing the centralizing tendencies of monarchs. For instance, during the reign of Edward I, knights played a critical role in the confirmation of the Magna Carta’s principles, advocating for limitations on royal power. This demonstrates how their political activism contributed to the development of constitutional frameworks.

To understand their impact, compare the English model with continental systems. In France, knights were less integrated into formal parliamentary structures, as the Estates-General remained dominated by the nobility and clergy. However, in regions like Catalonia, knights participated in the Corts, a proto-parliamentary assembly, where they negotiated fiscal and legal matters alongside other estates. This comparative analysis highlights the variability of knightly influence but also its consistent role in fostering dialogue between rulers and the governed.

A cautionary note is warranted: the political activity of knights was not universally democratic. Their representation often favored the interests of the landed elite, excluding peasants and townspeople. Yet, their involvement in parliamentary systems introduced principles of consultation and consent, which would later evolve into broader democratic ideals. For modern readers, this historical dynamic offers a lesson in the incremental nature of political reform, where even limited participation can sow the seeds of systemic change.

In conclusion, the influence of medieval knights on parliamentary systems was both profound and nuanced. By bridging the gap between local communities and central authority, they helped establish mechanisms of governance that prioritized negotiation over coercion. Their legacy is evident in the enduring structures of representative democracy, reminding us that political evolution often begins with the actions of privileged few, gradually expanding to encompass the many.

Understanding Bedroom Politics: Power, Intimacy, and Personal Relationships Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, many medieval knights were politically active, as they often served as advisors, administrators, or representatives of their lords or monarchs.

Yes, knights frequently held political offices such as sheriffs, castellans, or members of local and regional councils, depending on their rank and influence.

Knights influenced politics through military service, land ownership, and their roles in feudal hierarchies, often acting as intermediaries between lords and peasants.

Yes, knights were often chosen for diplomatic missions due to their status, loyalty, and ability to represent their lords or monarchs in negotiations with other powers.