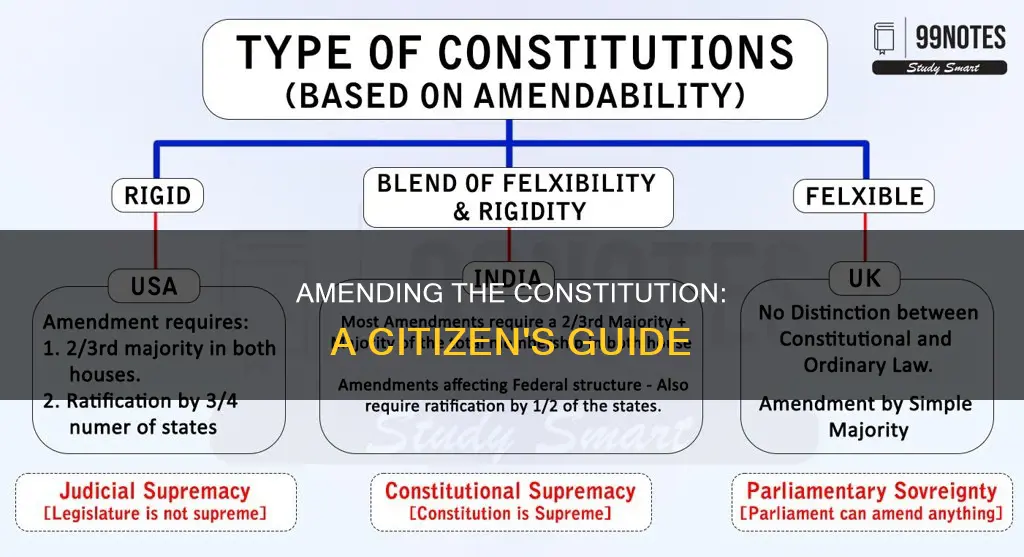

The process of proposing constitutional amendments in the United States is outlined in Article V of the Constitution. This article establishes two methods for proposing amendments: the first requires a two-thirds vote in both the House and the Senate, while the second involves a convention called by Congress upon the request of two-thirds of the state legislatures. While constitutional amendment proposals are common, few make it to the states for ratification. The last proposed amendment approved by Congress was the District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment in 1978, which sought to grant the district voting rights without statehood.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Who can propose constitutional amendments? | Any member of Congress, or two-thirds of the state legislatures |

| What is the first method? | Two-thirds of both Houses propose an amendment, which is then ratified by three-fourths of the state legislatures |

| What is the second method? | Two-thirds of the state legislatures request Congress to call a Convention for proposing Amendments |

| What is the role of Congress? | Congress may use its discretion to determine the scope of a Convention and whether to submit amendments for ratification |

| What is the role of the President? | The President does not need to approve a constitutional amendment |

| What is an example of a proposed amendment? | The District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment, which sought to give the District of Columbia membership in the House and Senate with full voting rights |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Article V conventions

Article V of the United States Constitution establishes two methods for proposing amendments to the Constitution. The first method requires both the House and the Senate to propose a constitutional amendment by a vote of two-thirds of the members present. This method has been used 33 times to propose amendments, 27 of which were ratified by three-fourths of the states.

The second method, which has never been used, is for Congress to call a Convention for proposing Amendments upon the request of two-thirds of the state legislatures (34 out of 50). This method is also referred to as an Article V Convention, state convention, or amendatory convention. While this method has been debated by scholars, there has never been a federal constitutional convention since the original one. However, at the state level, more than 230 constitutional conventions have been assembled in the United States.

There are differing opinions on the scope of an Article V convention. Some scholars argue that states can determine the scope by applying for a convention on a specific subject or group of subjects. On the other hand, some argue that the text of the Constitution only provides for a general convention, not limited to a particular matter.

The role of Congress in the Article V convention method is also a subject of debate. Congress might refuse to submit amendments resulting from an Article V convention to the states for ratification or determine that limited conventions are not allowed. Additionally, Congress has the power to review applications for a convention and decide on the mode of ratification, whether by state legislatures or conventions.

Informal Constitution Amendments: Who Holds the Power?

You may want to see also

State conventions

Article V of the U.S. Constitution establishes two methods for proposing amendments. The first method requires both the House and the Senate to propose a constitutional amendment by a vote of two-thirds of the Members present. Congress has followed this procedure to propose thirty-three constitutional amendments, which were sent to the states for potential ratification. However, only a small fraction of these amendments were ultimately ratified by the states.

The second method, which has never been used, involves state legislatures playing a more direct role in proposing amendments. Specifically, Congress shall call a Convention for proposing Amendments upon the request of two-thirds of the state legislatures. Scholars have debated the specifics of this method, including whether Congress must call a convention upon the request of two-thirds of the states, and whether states can determine the scope of a convention by applying for a convention on a specific subject or group of subjects.

Some commentators argue that states may or must determine the scope of an Article V convention by applying for a convention on a specific subject or group of subjects. For example, Congress would be obliged to call a convention only on the issues in the state applications, such as an amendment establishing congressional term limits or requiring a balanced federal budget. Other scholars argue that the text of the Constitution provides only for a general convention, one not limited in scope to considering amendments on a particular matter.

Despite the debates surrounding the convention method, it is important to note that any member of Congress can offer a proposed amendment to the Constitution. The proposal then needs to go through a series of committees to get a floor vote. In the House, the Judiciary Committee considers proposed constitutional amendments and must approve any before they are sent to the House floor for a full vote. Once on the floor, two-thirds of the House must approve the exact language of the amendment without making any changes. The identical approval process must then be conducted in the Senate and concluded by the end of that sitting of Congress.

Amending Club Rules: A Guide to Constitution Changes

You may want to see also

Ratification by three-fourths of states

The process of amending the Constitution of the United States is outlined in Article V of the Constitution. The Constitution provides two methods for proposing amendments: through Congress or a constitutional convention.

Congress can propose an amendment with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. This proposal is then sent to the states for ratification. Notably, the President does not have a constitutional role in this process.

The second method, which has never been used, involves a constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of the state legislatures. This convention proposes amendments, which are then sent to the states for ratification.

Once an amendment is proposed by either method, it must be ratified by three-fourths of the states (38 out of 50) to become part of the Constitution. This can be achieved through ratification by the legislatures of three-fourths of the states or by ratifying conventions in three-fourths of the states. Congress decides which mode of ratification will be used for each amendment.

The ratification process is administered by the Archivist of the United States, who heads the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Once the required number of authenticated ratification documents is received, the Archivist certifies that the amendment is valid and has become part of the Constitution. This certification is published in the Federal Register and U.S. Statutes at Large, serving as official notice to Congress and the nation.

In recent history, the signing of the certification has become a ceremonial event witnessed by dignitaries, including the President on some occasions. The entire process, from proposal to ratification, ensures that any changes to the Constitution undergo a rigorous and democratic review, reflecting the will of the people and preserving the integrity of the nation's founding document.

Amending California's Constitution: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Congressional blocking power

The US Constitution's Article V establishes two methods for proposing amendments. The first method requires both the House and the Senate to propose a constitutional amendment by a vote of two-thirds of the members present. Congress has followed this procedure to propose thirty-three constitutional amendments, which were sent to the states for potential ratification. However, constitutional amendment proposals are common during congressional terms, but few ever make it to the states as proposed amendments.

The second method, which has never been used, allows Congress to call a convention for proposing amendments upon the request of two-thirds of the state legislatures. Scholars debate whether Congress must call a convention upon the request of two-thirds of the states, and some argue that states may determine the scope of an Article V convention by applying for a convention on a specific subject or group of subjects. Congress has its own independent machinery to propose amendments and the power to review proposals, which some argue deprives the state convention method of its independence.

Congress might refuse to submit amendments that result from an Article V convention to the states for ratification. Even if two-thirds of the states applied for the same limited convention, Congress might use its discretion to determine that limited conventions are not allowed. This blocking power allows Congress to control the amendment process and prevent proposals from advancing to the state ratification stage, even if they have significant state support.

The Congressional blocking power has been a subject of debate and speculation among scholars. While some argue that Congress must call a convention upon the request of two-thirds of the states, others contend that Congress has the discretion to determine the scope and format of the convention. This includes the ability to refuse to submit amendments from an Article V convention to the states for ratification.

In conclusion, while any member of Congress can propose a constitutional amendment, the Congressional blocking power plays a significant role in determining which amendments advance to the state ratification stage. The two-thirds vote requirement in both the House and the Senate, as well as Congress's discretion over convention-proposed amendments, ensures that only a limited number of amendments progress beyond the proposal stage.

Prohibition's Constitutional Roots: Why an Amendment?

You may want to see also

The role of the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court plays a crucial role in the process of proposing and interpreting constitutional amendments in the United States. Firstly, the Court helps clarify the rules and procedures for proposing amendments. This includes interpreting Article V of the Constitution, which outlines the two methods for proposing amendments: through a two-thirds vote in both Houses of Congress or by calling a Convention upon the request of two-thirds of state legislatures. The Court's interpretations ensure that the amendment process follows the prescribed legal framework.

Secondly, the Supreme Court may be involved in resolving disputes or clarifying issues related to the scope and applicability of proposed amendments. For example, in the case of Nat’l Prohibition Cases (1920), the Court clarified that a two-thirds vote in each house refers to a vote of two-thirds of the members present, assuming a quorum, rather than a vote of two-thirds of the entire membership. Such interpretations shape how amendments are proposed and ensure the process's integrity.

Additionally, the Supreme Court plays a pivotal role in reviewing and interpreting ratified constitutional amendments. Once an amendment becomes part of the Constitution, the Court serves as the final arbiter of its meaning and application. It ensures that the amendment is correctly understood and applied across the nation, providing clarity and consistency in its implementation.

Furthermore, the Supreme Court can indirectly influence the proposal of constitutional amendments by issuing rulings that address the constitutionality of laws and government actions. When the Court finds that a law or policy violates the Constitution, it may prompt legislative action to propose amendments that address the identified issues. This dynamic interplay between judicial interpretation and legislative action helps shape the evolution of the Constitution over time.

Lastly, the Supreme Court's rulings on the constitutionality of proposed amendments themselves are crucial. The Court ensures that any amendments presented for ratification do not conflict with existing provisions of the Constitution. This role safeguards the integrity of the Constitution and prevents the introduction of amendments that may infringe on protected rights or alter fundamental aspects of the nation's governing framework.

Amendments to the Constitution: A Historical Overview

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Any member of Congress can propose a constitutional amendment.

The proposal needs to make its way through a series of committees to get a floor vote. Once on the floor, two-thirds of the House must approve the exact language of the amendment, with no changes. Then, identical approval processes must be conducted in the Senate and concluded by the end of that sitting of Congress.

Constitutional amendment proposals are common during congressional terms, but few ever make it to the states as proposed amendments. Since 1992, elected officials have introduced more than 1,400 proposed amendments in Congress for consideration, and not one has received the two-thirds vote.

One example is the District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment, which sought to give the District of Columbia membership in the House and Senate with full voting rights, but it did not grant statehood to the federal district. Another example is Rep. Andrew Ogles' proposal that "no person shall be elected to the office of the President more than three times".

Article V establishes an alternative method for amending the Constitution by a convention of the states. This method has never been used, but it involves Congress calling a convention for proposing amendments upon the request of two-thirds of the state legislatures.