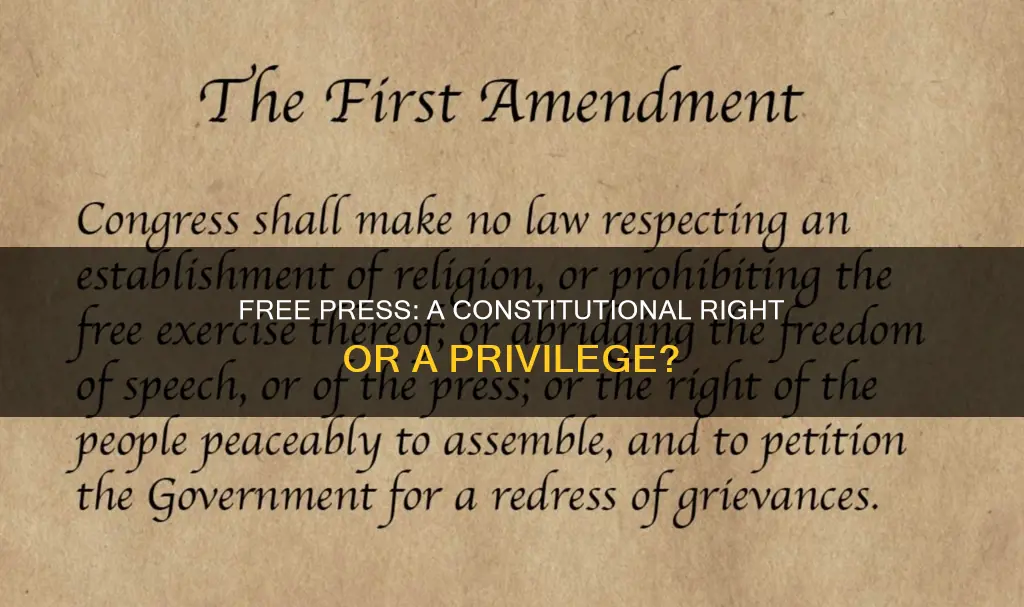

The First Amendment (Amendment I) to the United States Constitution, adopted on December 15, 1791, includes the freedom of the press as one of its tenets. It states that Congress shall make no law...abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press. The amendment's free press clause has been the subject of numerous Supreme Court decisions and interpretations, with some arguing for greater freedom for the institutional press. The amendment's role in protecting the free press has been significant, with early American courts debating the need for a free press guaranteed by the Constitution against concerns about defamation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date proposed | September 25, 1789 |

| Date ratified | December 15, 1791 |

| Author | James Madison |

| Type of law | Congress shall make no law |

| Topics covered | establishment of religion, free exercise of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, right to petition the government for redress of grievances |

| Landmark cases | Gitlow v. New York (1925), Near v. Minnesota (1931), New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The First Amendment

In another landmark case, New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), the Supreme Court ruled that the First Amendment protects the right to publish false or libelous statements about public officials, as long as there is no "actual malice". This case redefined the type of "malice" needed to sustain a libel case, with public officials needing to prove "clear and convincing evidence" of malice.

Louisiana's Constitution: Amended Many Times Over

You may want to see also

Free press vs. defamation laws

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution, passed by Congress on September 25, 1789, and ratified on December 15, 1791, guarantees several freedoms, including freedom of speech and freedom of the press. These freedoms are not absolute, however, and there are certain limitations, such as hate speech and "true threats," that are not protected by the First Amendment.

Defamation, which refers to the act of making false statements that harm someone's reputation, has existed as a common law claim for centuries and can act as a limit on freedom of speech and freedom of the press. Prior to 1964, defamation was not subject to First Amendment limitations, and it was regulated by state law. However, the Supreme Court's ruling in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan in 1964 significantly changed American defamation law by redefining the type of "malice" required for a successful libel claim. This case, which arose from the civil rights movement, established that public figures must prove "actual malice" or reckless disregard for the truth by "clear and convincing evidence," making it more difficult for them to win defamation lawsuits.

The Supreme Court has consistently attempted to balance the rights of a free press with the privacy and dignity of individuals, particularly those in government or public positions. While the press has traditionally been exempt from libel claims when reporting on public figures or the government if certain standards are met, the Court has afforded less protection to public figures and government officials in defamation cases. This is based on the principle that debate on public issues should be robust and uninhibited, and that erroneous statements are inevitable in free debate.

The distinction between fact and opinion in defamation cases can be nuanced, and several factors must be considered, such as the context in which the statement was made and whether a reasonable person would interpret it as fact or opinion. Commentary on matters of public interest is generally afforded greater protection, even if it contains false statements, as it contributes to important discourse. However, false statements that harm an individual's reputation can still result in legal consequences, including financial damages or, in some cases, criminal charges.

Constitutional Amendments: Understanding the Approval Process

You may want to see also

The institutional press

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution, adopted on December 15, 1791, explicitly states that "Congress shall make no law...abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press." This amendment, part of the Bill of Rights, guarantees the freedom of the press as a fundamental right.

In another case, Justice Potter Stewart argued that the separate mention of freedom of speech and freedom of the press in the First Amendment acknowledges the press's critical role in American society. This role necessitates governmental sensitivity and special consideration. However, the Court has also ruled that generally applicable laws do not violate the First Amendment simply because they may incidentally affect the press.

Despite the expanded protections for the institutional press, the First Amendment does not grant the media the privilege of special access to information, such as in prisons. Additionally, the constitutional rights to free speech and a free press are not absolute and must be balanced against the interests of society and the government.

In conclusion, while the First Amendment guarantees freedom of the press, the institutional press does not enjoy greater freedom from governmental regulations than non-press entities. However, the courts have acknowledged the unique role of the press in society and extended protections accordingly, while also recognizing the need for a balance with other societal interests.

Amending the Constitution: What's Next?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Freedom of speech

The First Amendment (Amendment I) to the United States Constitution was adopted on December 15, 1791, as one of the ten amendments that constitute the Bill of Rights. It states that "Congress shall make no law...abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press...". This amendment was designed to safeguard individual liberties and restrict governmental power.

The First Amendment protects the right to free speech and a free press as fundamental constitutional rights. It ensures that the government cannot censor or restrict the media or prevent individuals from expressing their opinions, even if they are critical of the government. This amendment also guarantees the freedom to assemble peaceably and petition the government for redress of grievances.

The Supreme Court has consistently affirmed the importance of a free press, recognising that laws targeting the press or treating different media outlets differently may violate the First Amendment. For example, in Grosjean v. Am. Press Co. (1936), the Court held that a tax exclusively on newspapers violated the freedom of the press. The Court has also ruled that the First Amendment protects the right to publish false or libelous statements about public officials, as open discourse about the government and public affairs is critical to a democracy.

While the First Amendment guarantees freedom of speech and the press, it is not absolute. The Supreme Court has recognised that these rights need to be weighed against the interests of society and the government. For instance, in Near v. Minnesota (1931), the Court established the doctrine of prior restraint, holding that a law allowing the state to prevent the publication of certain information constituted censorship and violated the First Amendment.

In conclusion, the First Amendment to the United States Constitution protects the rights of individuals and the press to free speech and expression, ensuring a free flow of information and ideas in society. These rights are fundamental to a democratic society and have been upheld and expanded by the Supreme Court over the years.

Civil Rights Act: Constitutional Amendments Explained

You may want to see also

The right to petition

The First Amendment (Amendment I) to the United States Constitution, passed by Congress on September 25, 1789, and ratified on December 15, 1791, includes the right to petition the government for a redress of grievances. This right was also included in the 1215 Magna Carta and the 1689 English Bill of Rights.

The First Amendment states that "Congress shall make no law... abridging... the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances." This right to petition the government is a fundamental part of the Bill of Rights, which was authored by James Madison and designed to safeguard individual liberties and restrict governmental power.

While the First Amendment guarantees the right to petition, it does not grant the media or individuals unrestricted access to government information. In the Houchins case, the Supreme Court held that the Free Press Clause does not confer on the press the power to compel the government to furnish information that is not available to the general public. However, the Court has also recognised that the press plays a critical role in disseminating news and information and is therefore entitled to heightened constitutional protections and governmental sensitivity.

In conclusion, the right to petition the government for a redress of grievances, as guaranteed by the First Amendment, is a fundamental aspect of American democracy. It empowers citizens to hold their government accountable and ensures that their concerns are addressed. This right has been upheld and expanded upon by the Supreme Court, recognising the critical role of a free press in a democratic society.

Hughes Amendment: Constitutional or Overreach?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, the First Amendment (Amendment I) to the United States Constitution includes the right to freedom of the press.

The First Amendment states that "Congress shall make no law...abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press". This was adopted on December 15, 1791, as one of the ten amendments that constitute the Bill of Rights.

The free press clause acknowledges the critical role played by the press in American society. It requires sensitivity to that role and to the special needs of the press in performing it effectively.

While the First Amendment guarantees freedom of the press, this right is not absolute and needs to be weighed against the interests of society and the government. For example, the Supreme Court has ruled that generally applicable laws do not violate the First Amendment, even if they incidentally affect the press.

![First Amendment: [Connected eBook] (Aspen Casebook Series)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61-dx1w7X0L._AC_UY218_.jpg)