The United States Constitution was designed to endure, and amending it is a difficult and time-consuming process. Article V of the Constitution outlines two methods for amending the nation's frame of government. The first method, which has been used for all 33 amendments submitted to the states for ratification, involves a proposal by Congress with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. The second method, which has never been used, is a constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of the state legislatures. While the process of amending the federal Constitution is challenging, state constitutions are amended more frequently and offer multiple paths for modification, including citizen-initiative processes in 17 states.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Authority to amend the Constitution | Article V of the Constitution |

| Amendment proposal | Congress with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate |

| Alternative amendment proposal | Constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of state legislatures |

| Number of amendments to the Constitution | 27 |

| Number of measures to amend the Constitution proposed in Congress | More than 10,000 |

| Number of amendments submitted to states for ratification | 33 |

| Number of amendments ratified by states | 27 |

| Number of amendments still open and pending | 4 |

| Number of state constitutional amendments | Around 7,000 |

| Number of states with citizen-initiative processes for amendments | 17 |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- The US Constitution can be amended via a constitutional convention

- State constitutions are easier to amend than the federal Constitution

- The first 10 amendments were ratified and adopted simultaneously

- The Archivist of the US administers the ratification process

- The President does not have a constitutional role in the amendment process

The US Constitution can be amended via a constitutional convention

The US Constitution is a document designed to endure for ages to come. As such, the process of amending it is deliberately difficult and time-consuming. The Constitution has been amended only 27 times since it was drafted in 1787, and none of these amendments have been proposed by constitutional convention.

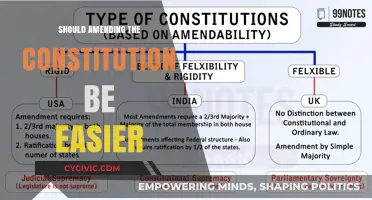

However, it is possible for the US Constitution to be amended via a constitutional convention. This is the second method provided for in Article V of the Constitution, which outlines the two methods for amending the nation's frame of government. The first method authorises Congress, with a two-thirds majority in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, to propose constitutional amendments. The second method allows two-thirds of state legislatures to call on Congress to hold a constitutional convention, with three-quarters of state legislatures then approving the amendment.

This duality is the result of compromises made during the 1787 Constitutional Convention. One group maintained that the national legislature should have no role in the constitutional amendment process, while another group contended that proposals to amend the Constitution should originate in the national legislature and be ratified by state legislatures or state conventions.

Despite this provision, a new Constitutional Convention has never happened. However, the idea has its backers. A retired federal judge, Malcolm R. Wilkey, called a few years ago for a new convention, arguing that "the Constitution has been corrupted by the system which has led to gridlock, too much influence by interest groups, and members of Congress who focus excessively on getting reelected".

The process of amending the US Constitution is a challenging and lengthy one, and the convention option has yet to be invoked. However, it remains a valid method for proposing and ratifying amendments, distinct from the standard process of Congressional proposal and state ratification.

The Amendment: Paying Taxes is Necessary

You may want to see also

State constitutions are easier to amend than the federal Constitution

The US Constitution is notoriously difficult to change, with only 27 amendments since its inception. In contrast, state constitutions are much easier to modify, with amendments adopted regularly. The 50 state constitutions have been amended approximately 7,000 times. The ease of amending state constitutions is evident in the frequency of amendments, with some states, like Alabama, Louisiana, South Carolina, Texas, and California, amending their constitutions more than three to four times per year on average.

There are multiple paths for amending state constitutions, and these vary across states. State legislatures are responsible for generating the majority of constitutional amendments, with over 80% of amendments originating from them. However, the requirements for legislatures to craft amendments differ. Some states mandate majority support, while others require supermajority backing. Additionally, there are variations in whether legislative support must be expressed in a single session or across two consecutive sessions. The simplest route for legislative approval is to allow amendments by a majority vote in a single session, an option available in 10 states.

Citizens also play a role in initiating amendments, although this accounts for fewer than 2 out of 10 amendments adopted annually. Certain states, like California and Colorado, stand out for the swift consideration of citizen-initiated amendments. In 18 states, voters can place a constitutional amendment directly on the ballot without legislative involvement if they gather a sufficient number of signatures.

State constitutional conventions, although less frequent in recent decades, offer another avenue for amendments. From 1776 to 1986, 250 constitutional conventions were held across the 50 states. The last full-scale convention occurred in Rhode Island in 1986, resulting in eight amendments approved by voters out of 14 submitted.

The ease of amending state constitutions compared to the federal Constitution highlights a significant difference in the amendment process. While the US Constitution requires a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate to propose an amendment, state constitutions often provide more flexible paths for amendments, whether through legislative, citizen, or convention initiatives.

The Fourteenth Amendment: Citizenship, Due Process, and Equal Protection

You may want to see also

The first 10 amendments were ratified and adopted simultaneously

The United States Constitution is notoriously difficult to amend, and there are limited methods to do so. The authority to amend the Constitution is derived from Article V, which outlines a two-step process. Firstly, an amendment must be proposed, and secondly, it must be ratified.

The first ten amendments, known as the Bill of Rights, were ratified and adopted simultaneously four years after the Constitution was drafted in 1787. This was an unusual occurrence, and since then, the process has become more complex and time-consuming.

There are two methods for proposing amendments: the first requires a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, and the second involves two-thirds of state legislatures (34 out of 50) calling for a constitutional convention. To date, all proposed amendments have originated in Congress, and no amendments have been proposed by constitutional convention.

Once an amendment is proposed, it must be ratified. There are two methods for ratification: the first involves approval by three-fourths of the state legislatures (38 out of 50), and the second requires approval by ratifying conventions in three-fourths of the states. The choice of ratification method is determined by Congress, and both methods carry equal validity.

While the process for amending the U.S. Constitution is challenging, state constitutions are amended more frequently and with greater ease. State legislatures generate the majority of constitutional amendments, and citizen-initiated amendments also play a role.

Citing the US Constitution: APA Style for the Second Amendment

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The Archivist of the US administers the ratification process

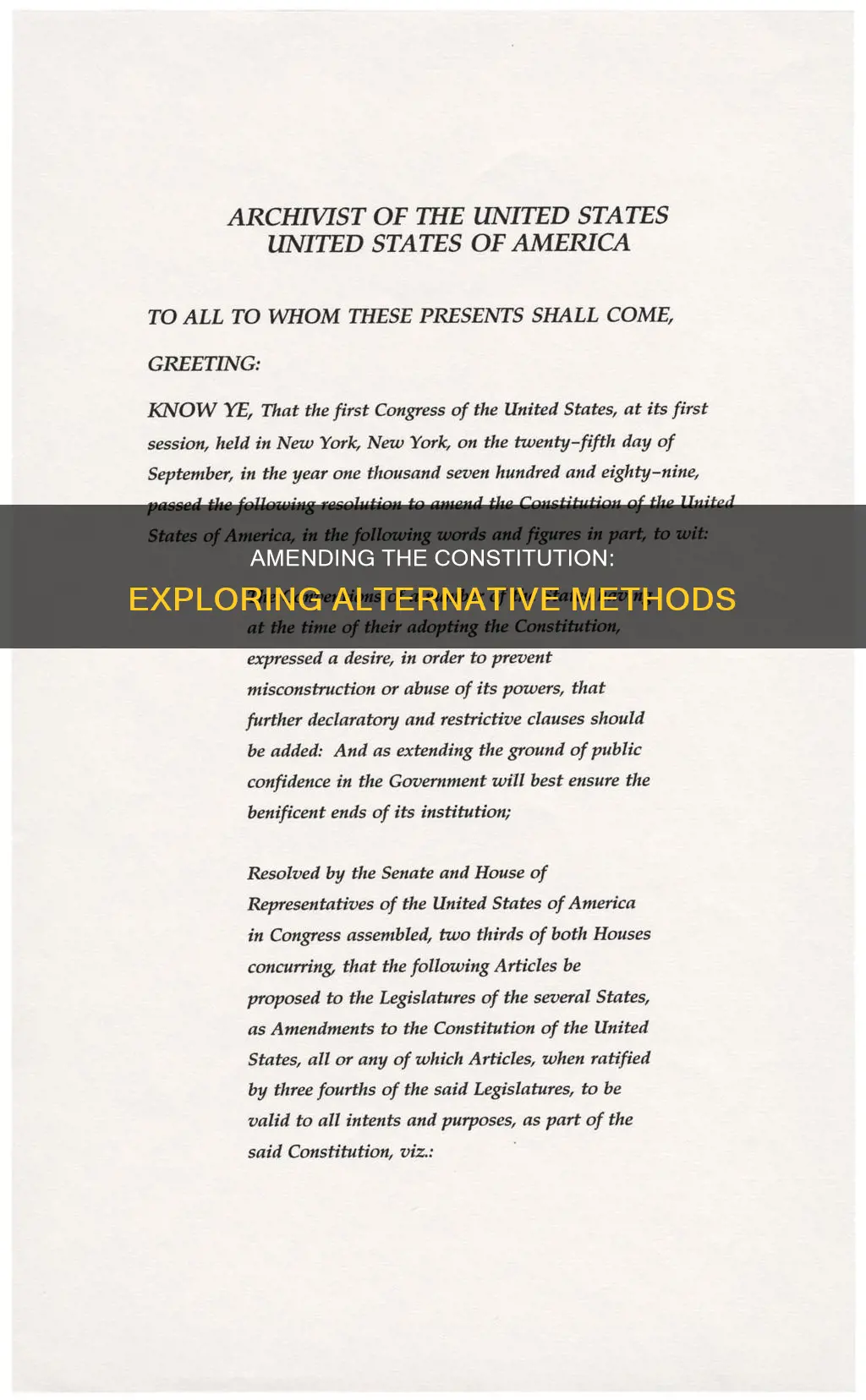

The Archivist of the United States is responsible for administering the ratification process of amendments to the US Constitution. The Archivist, who heads the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), assumes this role after Congress proposes an amendment.

The Archivist's role in the ratification process involves issuing a certificate proclaiming a particular amendment duly ratified and part of the Constitution. This occurs when legislatures of at least three-quarters of the states (38 out of 50) approve the proposed amendment. The Archivist's certification of the facial legal sufficiency of ratification documents is final and conclusive. However, it is important to note that the Archivist does not make any substantive determinations regarding the validity of state ratification actions.

The process begins with the Archivist submitting the proposed amendment to the states for their consideration. This is done by sending a letter of notification to each state governor, along with informational material prepared by NARA's Office of the Federal Register (OFR). Once a state ratifies a proposed amendment, it sends the Archivist an original or certified copy of the state action, which is then conveyed to the Director of the Federal Register.

The OFR examines the ratification documents for authenticity and legal sufficiency. If the documents are in order, the Director acknowledges receipt and maintains custody of them until the amendment is adopted or fails. The OFR then drafts a formal proclamation for the Archivist to certify that the amendment is valid and has become part of the Constitution. This certification is published in the Federal Register and U.S. Statutes at Large, serving as official notice to Congress and the nation that the amendment process is complete.

The current Archivist of the United States is Colleen Joy Shogan, who was nominated by President Joe Biden and confirmed by the Senate in May 2023. The Archivist is appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate and holds the responsibility for safeguarding and making available valuable federal government records, including the original Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and Bill of Rights.

Amending the Constitution: A Guide for Young Patriots

You may want to see also

The President does not have a constitutional role in the amendment process

The first method, a proposal by Congress, has been used for all amendments so far. In this process, two-thirds of both houses of Congress must vote to propose an amendment, and then three-quarters of the states must ratify it for it to become part of the Constitution. The second method, a constitutional convention, has never been used. However, it is a powerful tool that could enable state legislatures to "erect barriers against the encroachments of national authority".

Since the President does not have a constitutional role in the amendment process, the joint resolution does not go to the White House for signature or approval. Instead, the original document is forwarded directly to the National Archives and Records Administration's (NARA) Office of the Federal Register (OFR) for processing and publication. The OFR adds legislative history notes to the joint resolution and publishes it in slip law format. They also assemble an information package for the states, which includes formal "red-line" copies of the joint resolution and copies in slip law format.

While the President does not have a constitutional role in the amendment process, they may sometimes be involved in the ceremonial function of signing the certification of a new amendment. For example, President Johnson signed the certifications for the 24th and 25th Amendments, and President Nixon witnessed the certification of the 26th Amendment. However, this is not a constitutional requirement, and the President's involvement is purely ceremonial.

The Tenth Amendment: States' Rights and Powers

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The first step to amending the Constitution is for two-thirds of both houses of Congress to pass a proposed amendment.

The second step is for three-fourths of the states (38 out of 50) to ratify the proposed amendment.

While the two-step process is the most common method, there are other routes to amending the Constitution. One alternative method is for two-thirds of state legislatures to call for a Constitutional Convention, although this has never happened. State constitutions are also amended regularly and offer multiple paths for amendment, including citizen-initiative processes.