Myanmar has suffered civil war and military rule for decades, resulting in a complex constitutional history. The country has adopted three constitutions in 1947, 1974, and 2008, with the current constitution being enacted in 2011. The 2008 constitution, which replaced the 1974 constitution, has been criticized for its dominance by the military, with 25% of seats in parliament reserved for military representatives. Myanmar's constitutional roots are deeply tied to the ongoing conflict between ethnic minorities seeking a federal system and those advocating for a centralized government. The country's political landscape is further complicated by the clash of values between hierarchy/orthodoxy and plurality/equality. The Center for Constitutional Democracy (CCD) has been actively advising on constitutional reforms, and the National Unity Government of Myanmar, formed by legislators elected in 2020, is working on a constitution-making process. Myanmar's commitment to international human rights treaties, such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), has been questioned due to reservations and objections made by other countries.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of Constitutions | 3 |

| First Constitution | 1947 |

| Second Constitution | 1974 |

| Current Constitution | 2008 |

| Number of Chapters in Current Constitution | 15 |

| Separation of Powers | Legislature, Judiciary, and Executive |

| Percentage of seats in Parliament reserved for members of the military | 25% |

| Children's Rights | Preservation of identity, right to life, parental guidance, survival and development |

| Dialogue and International Cooperation | Encouraged |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The history of Myanmar's constitution

Myanmar has suffered civil war and military rule for decades, with underlying constitutional roots. The country has experienced long periods of non-constitutional rule, where military governments ruled without a clear constitutional basis.

Myanmar gained independence from the British Empire in 1948. Its first constitution as an independent country was written in 1947 when the British government and the interim government of General Aung San reached an agreement on full independence. The 1947 Constitution was suspended when the Myanmar military seized power and formed the Revolutionary Council of the Union of Burma, led by General Ne Win.

In 1962, a coup d'état took place, and a military government was established. This government ruled without a constitution for 12 years. In 1974, the military institutionalized its rule by adopting a new constitution, which was the second constitution of Myanmar. It created a unicameral legislature called the People's Assembly, represented by members of the Burma Socialist Programme Party as the only legal party. Each term was 4 years, and Ne Win became president at this time.

In September 1988, the military, under the guise of the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), suspended the 1974 constitution. In 1990, they issued a declaration that a new constitution should be drawn up, but many viewed this as a delaying tactic to remain in power. The SLORC called a constitutional convention in 1993, but it was suspended in 1996 when the National League for Democracy (NLD) boycotted it, calling it undemocratic. The constitutional convention was called again in 2004, but without the NLD. Myanmar remained without a constitution until 2008.

In 2008, Myanmar adopted its third constitution, which was published in September after a referendum and came into force on 31 January 2011. This constitution allowed for a partially civilian government, and in 2010, the first elections were held. The 2008 Constitution is the present constitution of Myanmar. However, it reserves 25% of seats in parliament for members of the military, with the most powerful posts given to active-duty or retired generals.

In 2020, the National League for Democracy won the elections, and a government was formed, the National Unity Government of Myanmar. However, on 1 February 2021, the army seized power again, dissolved the civilian government, and declared a state of emergency.

Supreme Court: Non-Citizens' Constitutional Rights

You may want to see also

The role of the military in constitutional change

Myanmar has suffered civil war and military rule for decades, with the country being ruled by military juntas for most of its history. The Tatmadaw (Myanmar Armed Forces) has exercised direct control several times since the country's independence in 1948.

The 2008 Constitution, the country's third constitution, was published in September 2008 after a referendum and came into force on 31 January 2011. Notably, the 2008 Constitution was crafted by a military junta, led by Senior General Than Shwe. This constitution provides the legal basis for the military to maintain control of the democratization process.

The 2008 Constitution contains several provisions that ensure the military retains significant control of the government. Firstly, it reserves 25% of seats in both houses of the Assembly of the Union (Pyidaungsu Hluttaw) for military representatives, including active and retired military officers. This presence gives the military effective veto power over any proposed constitutional amendments, as these require more than 75% of the vote in parliament.

Additionally, the 2008 Constitution does not incorporate an effective separation of powers between the president, parliament, judiciary, and armed forces. Instead, most state powers are vested in the president or subject to their influence, or concentrated in the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. This structure of military power remains largely undisturbed through the constitutional role of the commander-in-chief and the NDSC.

The military justifies its continued involvement in politics by arguing that Myanmar's transition to democracy is fragile and requires protection. However, critics argue that the military's ability to veto constitutional changes limits democratic reforms and protects its economic and political interests.

Despite some democratic progress, the military continues to play a central role in Myanmar's government and is poised to reestablish direct control if necessary. The civilian government, led by the National League for Democracy (NLD), has attempted to reduce the military's role, but these efforts have been largely unsuccessful due to the military's constitutional powers.

Murder in Arizona: Death Penalty for 1st Degree?

You may want to see also

The impact of civil conflict on constitutional roots

Myanmar has been plagued by civil conflict and military rule for decades, both of which have constitutional roots. The civil conflict in Myanmar stems from ethnic discord, with ethnic minorities advocating for a federal system that allows them to govern themselves, while others argue for a centralised government to maintain unity. This clash of ideologies reflects a broader conflict between values of hierarchy and orthodoxy versus plurality and equality.

The country's history of military rule has significantly influenced its constitutional trajectory. Myanmar has had three constitutions: in 1947, 1974, and 2008. The first constitution was suspended when the Myanmar military seized power in 1962, leading to the enactment of the second constitution in 1974. This constitution was modelled after the constitutions of the Eastern Bloc and established a unicameral legislature called the People's Assembly.

The military's grip on power continued with the suspension of the 1974 constitution in 1988, when the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) took control. Despite calling for a new constitution, the military's actions were seen as a tactic to prolong their rule. The 1993 constitutional convention was marred by the boycott of the National League for Democracy (NLD), who deemed it undemocratic. Myanmar remained without a constitution until 2008, when the military government proposed a new constitution that was put to a public referendum.

The 2008 Constitution, currently in force, grants significant control to the Myanmar Armed Forces (Tatmadaw), with 25% of parliamentary seats reserved for serving military officers. This constitution has been criticised and repudiated by the exiled National Unity Government (NUG) and ethnic armed organisations, who advocate for a democratic federal state. The ongoing civil war since 2021, triggered by the coup d'état and the violent suppression of anti-coup protests, has further highlighted the impact of constitutional roots on the conflict.

The civil conflict in Myanmar has had devastating consequences, including escalating human rights violations, the use of war crimes, and the targeting of civilians by both the military and resistance forces. The conflict has also led to the internal displacement of millions, widespread destruction of civilian buildings, and a deteriorating humanitarian situation. The United Nations estimates that 17.6 million people require humanitarian assistance as a result of the conflict. Additionally, the conflict has provided an opportunity for external actors like China to expand their influence and pursue their regional ambitions.

Magic Kills: Powering Up with Every Enemy Defeat

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The current constitutional status of Myanmar

Myanmar has had a tumultuous history, with civil war and military rule dominating for decades. The country has been ruled by military juntas for most of its existence since independence.

Myanmar's first constitution was adopted by a constituent assembly and enacted for the Union of Burma in 1947. This constitution was developed in consultation with various ethnic groups, including the Chin, Kachin, and Shan people, who were promised full autonomy in internal matters. However, this constitution was suspended in 1962 when the Myanmar military seized power and formed the Revolutionary Council of the Union of Burma, led by General Ne Win.

A second constitution was enacted in 1974, creating a unicameral legislature called the People's Assembly (Pyithu Hluttaw). This constitution was approved in a 1973 referendum and was modelled after the constitutions of the Eastern Bloc. Each term was set at four years.

In September 1988, the military, under the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), seized power again and suspended the 1974 constitution. They declared that a new constitution should be drafted, but many viewed this as a delaying tactic to prolong their rule. The SLORC attempted constitutional conventions in 1993 and 2004, but these were boycotted by the National League for Democracy (NLD) and deemed undemocratic.

Myanmar was without a constitution until 2008, when the military government released its proposed constitution for a public referendum as part of its roadmap to democracy. The 2008 Constitution, the country's third, came into force on 31st January 2011. This constitution allows for a partially civilian government, with 25% of parliamentary seats reserved for serving military officers.

The 2008 Constitution is the current constitution of Myanmar, and it grants significant control to the Tatmadaw (Myanmar Armed Forces). The ruling and opposition parties have acknowledged the need for amendments to reduce military dominance. However, proposed changes to most parts of the constitution require approval from more than 75% of both houses of the Assembly of the Union, followed by a referendum with at least 50% approval from registered voters.

The National League for Democracy, the largest civilian political party, won the 2020 elections. However, on 1st February 2021, the military once again seized power, dissolved the civilian government, and declared a state of emergency. The legislators elected in 2020 formed the National Unity Government (NUG), which has been implicitly recognised by the United Nations and ASEAN. The Center for Constitutional Democracy (CCD) is advising the NUG on the constitution-making process and increasing constitutional knowledge.

The Constitution's Ink: A Historical Mystery Unveiled

You may want to see also

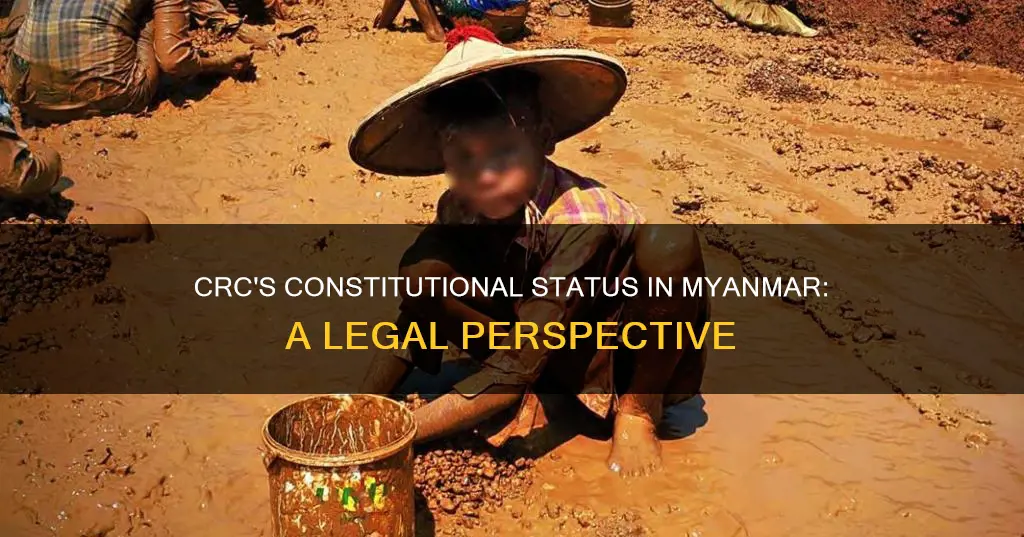

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)

The CRC defines a child as anyone under the age of 18 and outlines a range of rights and provisions that should be upheld by governments and other concerned parties. These include the right to an identity, non-discrimination, the best interests of the child being a primary consideration, and the right to express views and be protected from interference with privacy.

Myanmar's adherence to the CRC is significant given the country's history of military rule and civil conflict, which have had a detrimental impact on children's rights. Since 2002, the Center for Constitutional Democracy (CCD) has been advising those in Myanmar who aspire for a government based on plurality and equality. The CCD has worked to empower individuals to actively participate in the peace process and constitutional drafting, providing materials and support for training women in political and NGO leadership roles.

Despite these efforts, concerns have been raised about the lack of conformity between Myanmar's national legal framework and the CRC. For instance, the Citizenship Act, the Village and Towns Acts, and the Whipping Act have been identified as conflicting with the CRC's principles. Additionally, laws related to freedom of expression, association, and child labour have been questioned.

Myanmar's 2008 Constitution, which is currently in force, also grants substantial control to the military, with 25% of parliamentary seats reserved for serving military officers. This has likely influenced the implementation and protection of children's rights in the country.

Who Really Wrote the Constitution and the Declaration?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The CRC is the Convention on the Rights of the Child. It outlines the rights of children, including the right to an identity, the right to life, and the right to express their views.

Myanmar has had three constitutions: in 1947, 1974, and 2008. The current constitution, enacted in 2008, is dominated by the military, with 25% of seats in parliament reserved for military representatives.

Myanmar has been reviewed by the Committee on the Rights of the Child, which expressed appreciation for Myanmar's withdrawal of reservations on Articles 15 and 37 of the Convention. However, the Committee also noted a lack of conformity between Myanmar's legal framework and the CRC, specifically regarding the Citizenship Act, the Village and Towns Acts, and the Whipping Act.

![Burma Superstar: Addictive Recipes from the Crossroads of Southeast Asia [A Cookbook]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/91cTcf1-g4L._AC_UL320_.jpg)