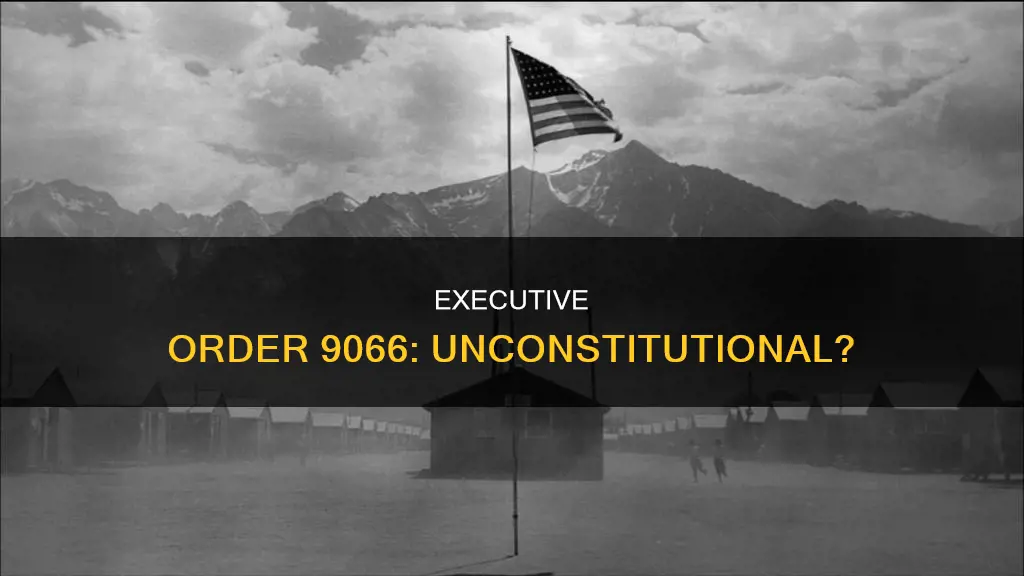

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans and people of Japanese descent from the West Coast to relocation centers further inland. This order was issued in response to fears of espionage and sabotage after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the safety concerns of America's West Coast. The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the order in Korematsu v. United States, ruling that the detention was a “military necessity” not based on race. However, the decision was controversial, with dissenting justices arguing that the order violated the constitutional rights of those affected and legalized racism. The American internment policy has since been criticized, and Congress apologized and provided restitution payments to survivors in 1988.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date of issue | February 19, 1942 |

| Issued by | President Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Targeted | People of Japanese ancestry |

| Number of people affected | More than 120,000 |

| Number of camps | 10 |

| Nature of violation | Racism, violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, violation of constitutional rights |

| Legal challenges | Korematsu v. U.S., Hirabayashi v. United States |

| Outcome | The Supreme Court ruled that the order was a "military necessity" |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Korematsu v. United States

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the removal of people of Japanese ancestry from designated military areas and communities in the United States. This order led to the detention of over 100,000 individuals, primarily Japanese-Americans, in internment camps during World War II.

Fred Korematsu, a 23-year-old Japanese-American man, refused to comply with Civilian Exclusion Order No. 34, which was issued under Executive Order 9066. He challenged the order on the grounds that it violated the Fifth Amendment, arguing that it infringed on the constitutional rights of Americans of Japanese ancestry. Korematsu was arrested and convicted of violating military orders, and his case, "Korematsu v. United States," eventually made its way to the Supreme Court.

In a 6-3 decision announced on December 18, 1944, the Supreme Court ruled that the detention of Japanese-Americans was a "military necessity" and upheld the conviction. The majority opinion, written by Justice Hugo Black, asserted that the need to protect against espionage outweighed the rights of Americans of Japanese ancestry. Black denied that racial prejudice played a role in Korematsu's exclusion from the military area.

However, the decision was not without dissent. Justice Robert Jackson argued that Korematsu had been convicted of "an act not commonly thought a crime," simply for being present in the state where he was a citizen. Justice Frank Murphy strongly opposed the decision, calling the government's order the "legalization of racism" and a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. He emphasized that the exclusion order fell into ""the ugly abyss of racism."

The "Korematsu v. United States" case has been a controversial chapter in American history. While the Supreme Court upheld the conviction, the decision has been criticized for validating racial discrimination and infringing on the constitutional rights of Japanese-Americans. The case highlights the complex balance between national security concerns and the protection of individual civil liberties, even during times of war.

The Constitution's Unkept Promise: Black Equality

You may want to see also

The legality of racism

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from designated military areas and surrounding communities. This order led to the incarceration of over 120,000 Japanese Americans in ten different camps across the United States, despite two-thirds of them being US citizens. The order also affected people of Italian and German heritage.

While the language of the order did not specify any particular ethnic group, it was largely Japanese Americans who were targeted and forced to leave their homes, with only a week to dispose of their belongings, and relocate to "relocation centers" or internment camps. This was due to increased anti-Japanese sentiment and distrust following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the US's entry into World War II.

The legality of Executive Order 9066 was challenged in the Supreme Court case Korematsu v. United States. Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu, a US citizen of Japanese ancestry, refused to comply with the order and was arrested and convicted of violating military orders. The Supreme Court, in a 6-3 decision, ruled that the detention was a "'military necessity' and upheld the constitutionality of the order, stating that it was not based on race.

However, there were strong dissenting opinions from Justices Robert Jackson, Owen Roberts, and Frank Murphy, who argued that the order violated the constitutional rights of those detained and that it amounted to "the legalization of racism," falling into "'the ugly abyss of racism.'" They highlighted that the order's broad provisions and distinctions based on color and ancestry were inconsistent with American traditions and ideals.

In subsequent years, the American internment policy has faced harsh criticism, and Congress has acknowledged the wrongs committed. As part of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, Congress apologized "on behalf of the people of the United States for the evacuation, relocation, and internment of such citizens and permanent resident aliens," and provided restitution payments to survivors of the camps.

The Cabinet's Role in the Executive Branch

You may want to see also

Constitutional racial discrimination

Executive Order 9066, issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from designated military areas. While the order did not specify any particular ethnic group, it resulted in the incarceration of over 120,000 Japanese Americans and Americans of Japanese ancestry in ten different camps across the United States. The order also impacted people of Italian and German heritage.

The constitutionality of Executive Order 9066 was challenged in the Supreme Court case Korematsu v. United States. Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu, a Japanese-American citizen, was arrested and convicted of violating military orders by failing to report to a relocation center. The Supreme Court, in a 6-3 decision, ruled that the detention was a "military necessity" and upheld the constitutionality of the order, stating that it was not based on race.

However, the decision was not without dissent. Justice Robert Jackson argued that Korematsu had been convicted of "an act not commonly thought a crime," simply for being present in the state where he was a citizen. He and two other dissenting justices, Owen Roberts and Frank Murphy, asserted that the order violated Korematsu's constitutional rights and that the court had validated the principle of racial discrimination in criminal procedure. Justice Murphy called the order "the legalization of racism," stating that it fell into ""the ugly abyss of racism"" and violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Despite the legal challenges, the detainees were not freed from the camps, and the American internment policy has been met with harsh criticism over the years. In 1948, a law provided reimbursement for property losses incurred by interned Japanese-Americans, and in 1988, Congress awarded restitution payments of $20,000 to each survivor of the camps as part of the Civil Liberties Act. Congress also apologized "on behalf of the people of the United States for the evacuation, relocation, and internment" of Japanese-American citizens and permanent resident aliens.

How Ohio's 1851 Constitution Influenced Voting Rights

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$56.46 $59

$9.99 $19.99

$32.64

Due process

Executive Order 9066, issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, authorized the forced removal and detention of all persons deemed a threat to national security, specifically targeting those of Japanese ancestry. This order led to the incarceration of over 120,000 Japanese Americans in ten different camps across the United States, with a majority of them being U.S. citizens. The constitutionality of this order has been widely debated, and one key aspect of this debate is the violation of due process.

Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu, a 23-year-old Japanese-American man, refused to comply with the order and challenged its constitutionality. In the case of Korematsu v. United States, he argued that Executive Order 9066 violated the Fifth Amendment, as it deprived him of liberty and due process without fair legal recourse. Korematsu's case asserted that his incarceration was based solely on his race and ancestry, which he argued was an "otherwise innocent act" that should not be criminalized.

The Supreme Court, however, ruled against Korematsu in a 6-3 decision, stating that the federal government had the power to arrest and intern him under the executive order. Justice Hugo Black, writing for the majority, denied that the case was rooted in racial prejudice and instead emphasized the need to protect against espionage by Japan during wartime. The dissenting Justices, including Owen Roberts and Frank Murphy, strongly disagreed, stating that the order clearly violated constitutional rights and fell into "the ugly abyss of racism."

The violation of due process in the enforcement of Executive Order 9066 had significant consequences for Japanese Americans, who suffered incarceration, loss of liberty, and the disruption of their lives and communities. The lack of fair legal procedures and the targeting of a specific racial group continue to be debated and examined as a dark chapter in American history, highlighting the importance of upholding constitutional rights and freedoms for all individuals, regardless of race or ancestry.

Cabinet-Level Positions: Understanding the Key Duo

You may want to see also

Validity of the order

The validity of Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, has been a subject of debate and controversy. The order, issued in response to fears of espionage and sabotage following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, authorized the forced removal and incarceration of individuals deemed a threat to national security, particularly those of Japanese ancestry, from designated military areas on the West Coast.

The order itself did not specifically mention Japanese-Americans or any particular ethnic group. However, its implementation resulted in the relocation and detention of over 120,000 people, with two-thirds being Japanese-Americans, many of whom were born in the United States. The validity of the order was challenged in court cases, most notably Korematsu v. United States, where Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu, a Japanese-American, refused to comply with the order and was subsequently arrested and convicted of violating military orders.

The Supreme Court, in a 6-3 decision, upheld the validity of the order, stating that the detention was a "military necessity" and not based on race. The majority opinion asserted that the "martial necessity arising from the danger of espionage and sabotage" justified the military's evacuation order. However, this decision was not without dissent, with several justices strongly disagreeing and arguing that the order violated the constitutional rights of those affected.

Justice Robert Jackson, in his dissent, stated that Korematsu was convicted of "an act not commonly thought a crime," simply for being present in the state where he was a citizen and had lived his entire life. He and Justice Frank Murphy highlighted the racial implications of the order, with Murphy calling it "the legalization of racism" and a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Despite the dissenting opinions, the Supreme Court's decision set a precedent and validated the principle of racial discrimination in criminal procedure.

In subsequent years, the American internment policy faced harsh criticism, and Congress acknowledged the wrongdoings through restitution payments and an official apology as part of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. The Korematsu decision was also formally repudiated, with Justice Sonia Sotomayor stating that it was "gravely wrong the day it was decided" and had "no place in law under the Constitution."

George Mason's Thoughts on Creating a New Constitution

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Executive Order 9066, issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, violated the constitutional rights of Japanese Americans and Aleuts. The order led to the incarceration of over 120,000 Japanese Americans in 10 camps across the U.S. and the removal of people of Japanese ancestry from communities on the West Coast.

The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Executive Order in Korematsu v. United States, ruling that the detention was a “military necessity” not based on race. However, the decision was controversial, with three dissenting Justices stating that Korematsu's constitutional rights had been violated. In subsequent years, the American internment policy has faced harsh criticism, and Congress has apologized and provided restitution payments to survivors of the camps.

Executive Order 9066 was issued in response to fears generated by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, which made the safety of America's West Coast a priority. The order was also influenced by lobbyists from western states who pressured Congress and the President to remove persons of Japanese descent from the West Coast.