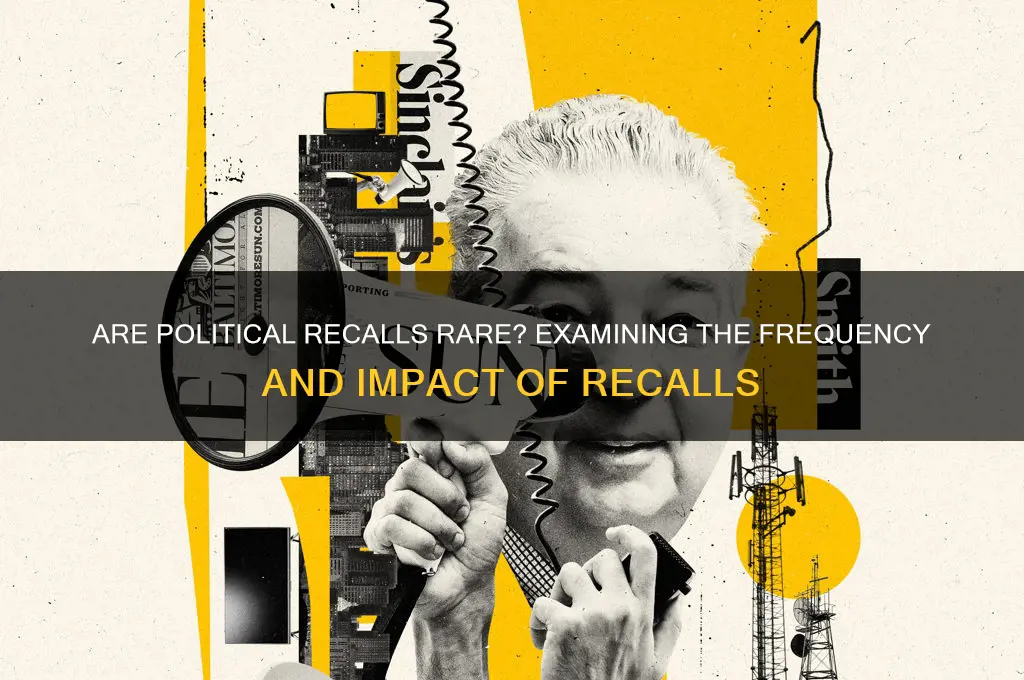

Political recalls, the process by which voters can remove an elected official from office before their term expires, are generally considered rare in most democratic systems. While the mechanism exists in various forms across different countries and states, its actual invocation and successful execution are infrequent events. This rarity can be attributed to the stringent requirements and high thresholds typically needed to initiate and complete a recall, such as gathering a significant number of signatures, demonstrating valid grounds for removal, and securing voter approval. Despite their infrequency, recalls often garner significant public attention when they do occur, as they reflect deep-seated dissatisfaction with an official's performance or conduct. Understanding the conditions under which recalls happen and their broader implications provides valuable insights into the dynamics of accountability and voter engagement in modern democracies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Frequency of Recalls | Relatively rare compared to other political events (e.g., elections). |

| Global Occurrence | More common in the United States, especially at the state and local levels. |

| Success Rate | Only a small percentage of recall attempts succeed in removing officials. |

| Legal Requirements | Strict criteria, including gathering a significant number of signatures. |

| Historical Examples | Notable cases include California Governor Gray Davis (2003) and Wisconsin Senator Scott Walker (2012). |

| Public Support Needed | Requires substantial public dissatisfaction with the targeted official. |

| Cost Implications | Expensive process, often requiring special elections. |

| Political Impact | Can be highly polarizing and disruptive to governance. |

| Timeframe | Typically a lengthy process, often taking months to complete. |

| Legal Challenges | Frequently subject to legal disputes over procedural validity. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Historical frequency of political recalls globally

Political recalls, the process by which voters can remove an elected official from office before their term expires, are a rare but significant tool in democratic systems. Historically, their frequency has been low, with only a handful of successful recalls occurring globally each decade. This rarity can be attributed to the stringent requirements and high thresholds typically needed to initiate and complete a recall, such as gathering a large number of signatures and securing a majority vote. For instance, in the United States, where recalls are most commonly discussed, only 11 state governors have faced recall elections since 1911, with only two being successfully removed: Governor Lynn Frazier of North Dakota in 1921 and Governor Gray Davis of California in 2003.

Globally, the picture is even sparser. Countries with recall mechanisms often face cultural, legal, or logistical barriers that limit their use. In Latin America, for example, Venezuela’s constitution allows for recalls, and President Hugo Chávez faced one in 2004, though he survived it. This remains one of the few high-profile examples outside the U.S. In Europe, recall provisions are even rarer, with most democracies relying on no-confidence votes by legislatures rather than direct voter action. This contrasts sharply with local-level recalls, which are more common in some regions, such as in certain municipalities in Canada and the U.K., where the stakes are lower and the process is less complex.

Analyzing the data reveals a clear pattern: recalls are most likely to occur in systems with strong direct democracy traditions and where public dissatisfaction reaches a critical point. For example, California’s recall of Governor Davis in 2003 was fueled by widespread anger over the state’s energy crisis and budget deficit. Similarly, the failed recall attempt against Governor Gavin Newsom in 2021 was driven by polarized responses to his handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. These cases underscore that while recalls are rare, they often serve as barometers of extreme public discontent.

To understand why recalls remain infrequent, consider the practical hurdles. In the U.S., organizers typically have a limited window—often 60 to 90 days—to collect signatures from a significant percentage of the electorate (e.g., 12% of voters in California). This requires substantial resources, organization, and public engagement. Even when recalls reach the ballot, incumbents often have the advantage of name recognition and established support networks. For instance, in 2012, Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker survived a recall election by leveraging strong conservative backing and outspending his opponents.

Despite their rarity, recalls play a crucial role in democratic accountability. They provide a check on elected officials who may have lost public trust but are not yet up for reelection. However, their infrequent use also highlights the importance of balancing direct democracy with stability. Too many recalls could lead to governance paralysis, while too few could leave voters without recourse. For citizens considering a recall, the key takeaway is to focus on clear, compelling reasons for removal and to mobilize early and effectively. History shows that while recalls are rare, they are not impossible—and when executed successfully, they can reshape political landscapes.

Theater as a Political Arena: Unveiling Society's Mirror on Stage

You may want to see also

Factors contributing to the rarity of recalls

Political recalls are rare, and this rarity can be attributed to a combination of procedural hurdles, strategic disincentives, and psychological barriers. The process itself is deliberately cumbersome, often requiring a multi-stage petition system where organizers must gather signatures from a significant percentage of the electorate—sometimes as high as 25% in certain jurisdictions. For example, in California, the 2003 recall of Governor Gray Davis succeeded only after organizers collected over 1.6 million valid signatures, a logistical feat that demands substantial resources and grassroots mobilization. This high threshold ensures that recalls are not initiated lightly, filtering out frivolous attempts and reserving the mechanism for cases of extreme public dissatisfaction.

Beyond procedural obstacles, political calculations often discourage recall efforts before they even begin. Incumbents and their allies frequently employ legal challenges, public relations campaigns, or procedural delays to undermine recall attempts. For instance, in Wisconsin’s 2011 recall elections, targeted lawmakers used legal maneuvers to invalidate signatures and delay the process, exhausting recall organizers’ resources. Additionally, the risk of backlash looms large: failed recalls can embolden incumbents and demobilize opposition, making future challenges even harder. This strategic calculus transforms recalls into high-stakes gambles, deterring all but the most determined or well-funded groups.

Psychological factors also play a role, as voters often exhibit a status quo bias, hesitating to disrupt established governance even when dissatisfied. Recalls require not just dissatisfaction but active, sustained engagement from a critical mass of voters. This is compounded by the "sunk cost fallacy," where constituents may rationalize sticking with an underperforming official rather than investing time and energy in a recall. For example, in the 2018 recall attempt of a Santa Clara County judge, despite widespread criticism, voter apathy and confusion about the process led to low turnout, ensuring the recall’s failure. Such dynamics highlight how human behavior reinforces the rarity of recalls.

Finally, the rarity of recalls is perpetuated by their limited historical success rate. Since 1911, only 11 state-level officials in the U.S. have been successfully recalled, compared to thousands of elected officials serving during that period. This track record creates a self-fulfilling prophecy: the perception that recalls are unlikely to succeed discourages potential organizers from even attempting them. Combined with the factors above, this historical context underscores why recalls remain an exceptional, rather than routine, feature of democratic governance.

Is Inside Politics Cancelled? Analyzing Its Relevance in Today's Media Landscape

You may want to see also

Comparison of recall rates across countries

Recall rates vary significantly across countries, reflecting differences in political culture, legal frameworks, and public engagement. In the United States, recalls are most commonly associated with state-level officials, particularly governors and legislators. California, for instance, has seen high-profile recalls, such as the 2003 removal of Governor Gray Davis and the 2021 failed attempt against Governor Gavin Newsom. Despite these examples, recalls remain rare at the federal level, with no U.S. senator or president ever being successfully recalled. This contrasts sharply with Venezuela, where the 2004 recall referendum against President Hugo Chávez demonstrated a more permissive approach to recalls at the highest levels of government.

In Europe, recall mechanisms are less common and often more restrictive. For example, Romania allows for the recall of mayors and local councilors but imposes strict conditions, such as requiring a higher turnout than the original election. This has resulted in very few successful recalls, highlighting the challenges of mobilizing voters for such initiatives. Conversely, countries like Switzerland and some Scandinavian nations rely more on direct democracy tools like referendums, which can indirectly influence political accountability but do not specifically target individual officials for removal.

Latin America presents a mixed picture, with countries like Peru and Ecuador incorporating recall provisions into their constitutions but applying them sparingly. In Peru, President Martín Vizcarra faced a recall attempt in 2020, though it was ultimately dismissed on procedural grounds. Ecuador’s 2018 referendum included a question on recalling President Lenín Moreno, which failed due to low public support. These cases underscore the importance of public sentiment and procedural hurdles in determining recall outcomes.

To compare recall rates effectively, consider the following steps: first, examine the legal thresholds for initiating a recall, such as the percentage of signatures required relative to the electorate. Second, analyze the frequency of successful recalls versus attempts, as this reveals both public engagement and the feasibility of the process. Finally, assess the cultural and historical context, as countries with stronger traditions of direct democracy tend to have higher recall activity. For instance, Venezuela’s 2004 referendum turnout was 70%, compared to California’s 61% in 2021, illustrating how cultural factors influence participation.

A cautionary note: while recalls can serve as a check on political power, they also risk destabilizing governance if used too frequently or frivolously. Countries with lower recall rates often have safeguards, such as requiring a valid reason for the recall or mandating a replacement election alongside the recall vote. Policymakers and citizens alike should weigh the benefits of accountability against the costs of political uncertainty when designing or invoking recall mechanisms.

Navigating Political Landscapes: A Guide to Critical and Informed Thinking

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Notable successful recall cases and their impact

Political recalls, while not commonplace, have left indelible marks on the political landscapes where they've occurred. One of the most notable successful recall cases is that of California Governor Gray Davis in 2003. Amidst a state energy crisis and a mounting budget deficit, voters successfully recalled Davis, replacing him with Arnold Schwarzenegger. This case stands out not only because it was the first successful recall of a California governor in over 80 years but also because it demonstrated the power of voter dissatisfaction to reshape state leadership mid-term. The impact was immediate and profound, signaling a shift in how governors approach crisis management and public perception.

Another significant recall occurred in Wisconsin in 2012, targeting State Senators who supported Governor Scott Walker's controversial budget repair bill, which limited collective bargaining rights for public employees. While Walker himself survived a recall election in 2012, two Republican state senators were removed from office. This case highlights the role recalls can play in holding legislators accountable for specific policy decisions, particularly those that provoke widespread public outcry. The aftermath saw a more polarized political environment in Wisconsin, with lasting effects on labor relations and legislative priorities.

In a more localized example, the 2013 recall of San Diego Mayor Bob Filner underscores the effectiveness of recalls in addressing personal misconduct. Accusations of sexual harassment led to a swift and decisive public response, culminating in Filner's resignation before the recall election could take place. This case serves as a cautionary tale for public officials, emphasizing the importance of ethical behavior and the consequences of failing to meet basic standards of conduct. It also illustrates how recalls can serve as a mechanism for restoring public trust in government institutions.

Comparatively, the 2021 recall attempt against California Governor Gavin Newsom provides insight into the challenges and limitations of the recall process. Despite significant opposition, Newsom survived the recall, which cost the state an estimated $276 million. This case raises questions about the practicality and fairness of recalls, particularly when they are driven by partisan politics rather than broad public consensus. It also highlights the importance of clear, compelling reasons for initiating a recall, as vague or politically motivated efforts are less likely to succeed.

In analyzing these cases, a key takeaway emerges: successful recalls are rare but impactful, often serving as turning points in political careers or policy directions. They require significant public mobilization, clear justification, and a focused strategy. For voters, recalls offer a powerful tool for accountability, but they must be wielded thoughtfully to avoid misuse or excessive political instability. Understanding these dynamics can help both citizens and officials navigate the complexities of this democratic mechanism more effectively.

Mastering Polite Communication: Simple Strategies for Gracious Interactions

You may want to see also

Challenges in initiating and executing political recalls

Political recalls, while a powerful tool for holding elected officials accountable, are fraught with challenges that often render them rare and difficult to execute. One of the primary hurdles is the stringent legal requirements that must be met to initiate a recall. In most jurisdictions, proponents must gather a significant number of valid signatures from registered voters within a tight timeframe, often ranging from 90 to 180 days. For example, in California, a recall petition requires signatures from 12% of the votes cast in the last gubernatorial election, a daunting task that demands substantial organizational resources and grassroots support.

Beyond the logistical nightmare of signature gathering, financial constraints pose another significant challenge. Recall campaigns are expensive, requiring funds for staff, legal fees, and outreach efforts. Unlike regular elections, recalls often lack the backing of established political parties or deep-pocketed donors, leaving proponents to rely on small contributions and volunteer efforts. This financial disparity can stifle even the most justified recall attempts, as seen in the 2021 California gubernatorial recall, where opponents of the recall vastly outspent proponents, contributing to its failure.

Even when a recall qualifies for the ballot, the process is far from over. The campaign phase introduces new challenges, including voter apathy and misinformation. Recall elections often occur outside the regular election cycle, leading to lower turnout. Additionally, incumbents typically wield the power of their office to counter the recall, using official communication channels and media coverage to their advantage. For instance, during the 2012 Wisconsin gubernatorial recall, Governor Scott Walker leveraged his position to highlight his policy achievements, effectively swaying public opinion in his favor.

Finally, the emotional and political backlash faced by recall proponents cannot be understated. Recalls are often perceived as divisive and destabilizing, leading to polarization within communities. Proponents may face personal attacks, harassment, or even legal challenges from opponents seeking to discredit the effort. This hostile environment discourages many from pursuing recalls, even when there is widespread dissatisfaction with an official’s performance.

In summary, while political recalls serve as a critical check on power, the challenges of signature collection, funding, campaigning, and societal backlash make them a rare and arduous endeavor. Overcoming these obstacles requires meticulous planning, broad-based support, and a resilient commitment to accountability.

Mastering Polite Texting: How to Communicate Respectfully with Your Teacher

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, political recalls are relatively rare in the United States. While recall laws exist in most states, successful recalls of elected officials, especially at the state or federal level, are infrequent due to the high bar for signature collection and voter turnout required.

Political recalls of state governors are extremely rare. Only two U.S. governors have been successfully recalled in history: Governor Gray Davis of California in 2003 and Governor Lynn Frazier of North Dakota in 1921.

Yes, political recalls are more common at the local government level, such as city councils, school boards, or mayors. Local recalls are easier to organize due to smaller populations and lower signature requirements, making them more feasible than state or federal recalls.

Political recalls are rare because they require significant time, resources, and voter engagement. Organizers must gather a large number of valid signatures, and a majority of voters must participate in the recall election, often with a high threshold for removal. These hurdles make recalls challenging to execute successfully.

![Dog Shock Collar with Remote Control- [Newly Upgraded] Dog Training Collar for Small Medium Large Dogs, Electric Collar for Dogs Training Rechargeable, Waterproof E Collars with Shock-Lock Keypad](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71E9BD-otgL._AC_UY218_.jpg)

![Total Recall (30th Anniversary) [4K + Blu-ray + Digital]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81nMf8FoERL._AC_UY218_.jpg)