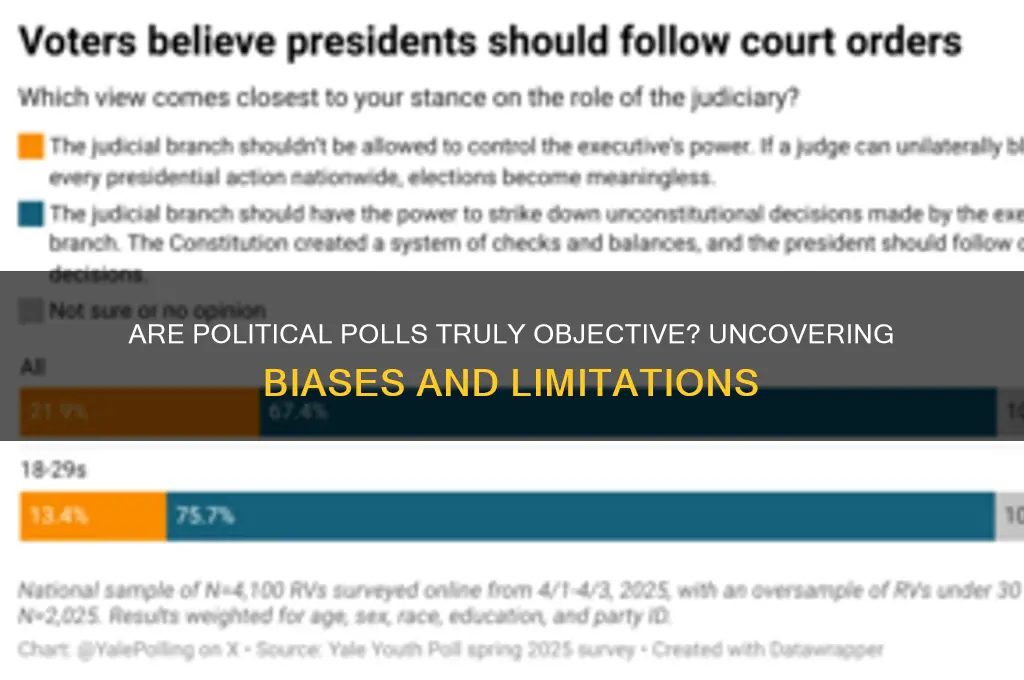

Political polls, often seen as a barometer of public opinion, are frequently scrutinized for their objectivity. While they aim to provide a snapshot of voter sentiment, their accuracy and impartiality depend on various factors, including methodology, sample size, and question framing. Critics argue that polls can be influenced by biases in survey design, media narratives, or the timing of data collection, potentially skewing results. Proponents, however, contend that when conducted rigorously and transparently, polls offer valuable insights into public attitudes. Ultimately, the objectivity of political polls hinges on the integrity of their execution and the context in which they are interpreted.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Bias in Question Wording | Questions can be framed to influence responses, leading to skewed results. |

| Sampling Methodology | Non-representative samples (e.g., convenience sampling) can introduce bias, while random sampling aims for objectivity. |

| Response Rates | Low response rates may lead to biased results if non-respondents differ significantly from respondents. |

| Timing of Polls | Polls conducted closer to elections may reflect more immediate sentiment, while earlier polls might capture different trends. |

| Weighting Adjustments | Pollsters adjust data to match demographic distributions, but subjective decisions in weighting can affect objectivity. |

| Sponsor Influence | Polls funded by partisan organizations may have inherent biases in methodology or presentation. |

| Margin of Error | All polls have a margin of error, and results within this range are statistically indistinguishable. |

| Public Opinion Fluidity | Political opinions can change rapidly, making polls snapshots in time rather than definitive predictions. |

| Non-Response Bias | Certain groups (e.g., younger voters) may be less likely to respond, skewing results. |

| Social Desirability Bias | Respondents may answer in ways they believe are socially acceptable rather than truthfully. |

| Technology and Mode | Online, phone, or in-person polling methods can yield different results due to varying respondent pools. |

| Transparency | Fully transparent methodologies enhance objectivity, while opaque methods raise concerns. |

Explore related products

$4.56 $20.99

What You'll Learn

- Pollster Bias: How pollsters' political leanings or funding sources influence question framing and results

- Sampling Methods: Whether poll samples accurately represent diverse demographics and political affiliations

- Question Wording: How phrasing affects responses, potentially skewing results toward desired outcomes

- Timing of Polls: How poll timing (e.g., before/after events) impacts public opinion and results

- Response Bias: How non-response or selective participation distorts poll outcomes and objectivity

Pollster Bias: How pollsters' political leanings or funding sources influence question framing and results

Political polls are often touted as impartial snapshots of public opinion, but the reality is far more nuanced. Pollster bias, whether intentional or subconscious, can subtly skew results, undermining their objectivity. This bias often stems from the political leanings of the pollsters themselves or the financial interests of their funding sources. For instance, a polling organization with ties to a particular political party might frame questions in a way that elicits responses favorable to that party’s agenda. Similarly, a poll funded by a corporation with a vested interest in a specific policy outcome may use leading language to sway public perception. These influences are not always overt but can significantly impact the reliability of the data.

Consider the mechanics of question framing. A seemingly neutral question can be manipulated to evoke a desired response. For example, asking, “Do you support increased government spending on healthcare?” may yield different results than, “Do you think higher taxes are justified to fund healthcare programs?” The former emphasizes the benefit, while the latter highlights the cost, potentially biasing responses based on how the question is posed. Pollsters with specific political leanings may instinctively choose wording that aligns with their worldview, even if unintentionally. This subtle manipulation can amplify certain viewpoints while downplaying others, distorting the true sentiment of the public.

Funding sources introduce another layer of complexity. Polls commissioned by political campaigns, advocacy groups, or corporations often serve strategic purposes. For instance, a poll funded by a fossil fuel company might ask questions that frame renewable energy as costly and unreliable, aiming to shift public opinion against green policies. Conversely, an environmental organization might sponsor a poll that emphasizes the urgency of climate action, using language that appeals to fear or moral obligation. The financial incentives behind these polls can drive pollsters to design questions that align with the sponsor’s goals, rather than seeking an unbiased assessment of public opinion.

To mitigate pollster bias, transparency is key. Pollsters should disclose their funding sources, political affiliations, and methodologies openly. Audiences must critically evaluate polls by examining the exact wording of questions, the sample size, and the demographic breakdown of respondents. For instance, a poll claiming 60% support for a policy is less credible if the sample disproportionately represents a specific age group or region. Practical tips for consumers of polling data include cross-referencing results from multiple sources, looking for consistency across polls, and being wary of outliers that may indicate bias. By adopting a skeptical yet informed approach, individuals can better discern the true objectivity of political polls.

Ultimately, while polls remain a valuable tool for gauging public sentiment, their objectivity is not guaranteed. Pollster bias, whether through political leanings or funding influences, can subtly shape question framing and results. Awareness of these dynamics empowers readers to interpret polling data more critically, ensuring they are not misled by skewed or manipulated findings. In an era where information is power, understanding the limitations of political polls is essential for making informed decisions.

Asking for Financial Help: A Guide to Polite and Effective Requests

You may want to see also

Sampling Methods: Whether poll samples accurately represent diverse demographics and political affiliations

Political polls often claim to capture the pulse of the electorate, but their accuracy hinges on one critical factor: sampling. A poll’s sample must mirror the population it aims to represent, including its demographic and political diversity. Without this, results can skew dangerously, misinforming both the public and policymakers. For instance, a 2016 U.S. presidential poll under-represented rural voters, contributing to its failure to predict Donald Trump’s victory. This example underscores the high-stakes consequences of sampling errors in political polling.

To achieve representativeness, pollsters employ various sampling methods, each with strengths and limitations. Probability sampling, such as random sampling, ensures every individual in the population has an equal chance of being selected, theoretically reducing bias. However, this method is costly and time-consuming, making it impractical for quick-turnaround polls. In contrast, convenience sampling, often used in online polls, relies on volunteers, leading to over-representation of certain groups (e.g., younger, more tech-savvy individuals) and under-representation of others (e.g., older adults or those without internet access). Pollsters must weigh these trade-offs carefully, balancing feasibility with accuracy.

Stratified sampling offers a middle ground by dividing the population into subgroups (strata) based on demographics like age, race, or political affiliation, then sampling proportionally from each. This method ensures diverse representation but requires detailed population data, which may not always be available. For example, a poll aiming to reflect the U.S. electorate might stratify by state, urban/rural status, and party affiliation, then adjust sample sizes to match census data. However, even stratified samples can falter if subgroups are misclassified or if certain demographics are harder to reach, such as non-English speakers or marginalized communities.

Practical challenges further complicate sampling accuracy. Response rates have plummeted in recent decades, with some polls achieving rates below 10%. Low response rates increase the risk of non-response bias, where those who do respond differ systematically from those who don’t. Pollsters often use weighting techniques to adjust for these discrepancies, but this relies on accurate demographic data and assumptions about non-respondents. For instance, if a poll under-samples Hispanic voters, weighting can correct this—but only if the pollster knows the correct population proportion and assumes non-respondents’ views align with respondents’ in the same demographic.

In conclusion, while sampling methods are essential for poll accuracy, no single approach guarantees perfect representation. Pollsters must navigate trade-offs between cost, speed, and inclusivity, while addressing challenges like declining response rates and hard-to-reach populations. For consumers of political polls, understanding these limitations is crucial. A poll’s credibility rests not just on its headline numbers but on the rigor of its sampling methodology. Always scrutinize how a poll was conducted before drawing conclusions—its accuracy may depend on it.

Don't Talk Politics Song: Navigating Unity Through Music in a Divided World

You may want to see also

Question Wording: How phrasing affects responses, potentially skewing results toward desired outcomes

The way a question is phrased in a political poll can significantly influence the responses received, often leading to skewed results that favor a particular narrative. Consider the subtle yet powerful difference between asking, "Do you support increased government spending on healthcare?" and "Do you think the government should allocate more taxpayer money to healthcare programs?" The first question frames the issue positively, emphasizing "support" and "healthcare," while the second introduces the potentially negative term "taxpayer money," which may trigger concerns about financial burden. This slight shift in wording can tilt responses, demonstrating how phrasing can manipulate public opinion.

To illustrate further, imagine a poll about climate change policies. A question like, "Should the government implement stricter regulations on industries to combat climate change?" presents a clear, action-oriented stance. In contrast, "Do you believe industries should face more regulations, even if it might cost jobs?" introduces a trade-off, potentially swaying respondents who prioritize employment. This example highlights how adding qualifiers or implications can steer answers in a desired direction. Pollsters must be mindful of such nuances to avoid inadvertently biasing their results.

When designing polls, follow these steps to minimize bias from question wording: first, use neutral language that avoids emotionally charged terms or leading phrases. Second, ensure the question is clear and concise, avoiding double-barreled queries that conflate multiple issues. Third, test the question on a small sample group to identify potential biases before full-scale deployment. For instance, a poll about gun control might ask, "What measures do you support to reduce gun violence?" instead of, "Should we ban guns to stop mass shootings?" The former invites a range of responses, while the latter presupposes a specific solution.

Despite best efforts, some biases are harder to eliminate. For example, the order of questions can influence responses, a phenomenon known as "question order effect." If a poll first asks about economic concerns and then about environmental policies, respondents might prioritize economic issues in subsequent questions. To mitigate this, randomize question order or group related topics together. Additionally, be cautious with "loaded questions" that contain assumptions or imply a correct answer. For instance, "How concerned are you about the government’s failure to address homelessness?" assumes failure, potentially skewing responses negatively.

In conclusion, question wording is a critical factor in the objectivity of political polls. By carefully crafting questions to be neutral, clear, and free of leading implications, pollsters can reduce bias and produce more accurate results. However, complete objectivity remains challenging due to inherent complexities in language and human psychology. Awareness of these pitfalls and proactive measures to address them are essential for anyone interpreting or conducting political polls.

Are Political Conversations Worth the Effort? A Thoughtful Debate

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Timing of Polls: How poll timing (e.g., before/after events) impacts public opinion and results

The timing of political polls can dramatically alter their results, often reflecting the immediate emotional and cognitive state of the public rather than their long-term views. For instance, a poll conducted immediately after a high-profile political debate may capture the initial reactions of voters, which are often swayed by performance rather than policy substance. These immediate responses can be volatile, influenced by factors like charisma, perceived gaffes, or even non-verbal cues, which may not align with a candidate’s actual qualifications or platform. Such polls, while revealing, must be interpreted with caution, as they may overrepresent transient sentiments rather than enduring opinions.

To illustrate, consider the 2016 U.S. presidential election, where polls taken immediately after the first debate showed a significant surge for Hillary Clinton. However, as days passed and media narratives evolved, subsequent polls began to reflect a more nuanced public opinion, with Donald Trump regaining ground. This example underscores the importance of timing: polls taken in the heat of the moment can amplify short-term fluctuations, while those conducted after a cooling-off period may better capture considered judgments. Pollsters and consumers of polling data alike must account for this temporal bias to avoid misinterpreting results as stable indicators of public sentiment.

Strategically timing polls can also be used to influence public perception, a tactic often employed by campaigns and media outlets. For example, releasing a poll showing a candidate’s lead just before a critical fundraising deadline can create a bandwagon effect, encouraging donors and undecided voters to align with the perceived frontrunner. Conversely, a poll highlighting a candidate’s weakness might be timed to coincide with opposition attacks, amplifying negative narratives. This manipulation of timing raises ethical questions about the objectivity of polls, as their release can become a tool for shaping opinion rather than merely reflecting it.

Practical tips for interpreting poll timing include examining the context in which the poll was conducted. Ask: Was it taken before or after a major event, such as a scandal, policy announcement, or international crisis? Was there sufficient time for the public to process the information, or was the poll designed to capture raw, immediate reactions? Cross-referencing multiple polls taken at different times can also help identify trends and filter out noise. For instance, if several polls taken over a week consistently show a shift, it’s more likely to reflect a genuine change in opinion than a single poll taken immediately after a high-impact event.

Ultimately, the timing of polls is a critical factor in their objectivity, as it can either distort or clarify public opinion. While polls are invaluable tools for gauging sentiment, their results must be contextualized within the temporal landscape of political events. By understanding how timing influences outcomes, stakeholders can better discern between fleeting reactions and lasting attitudes, ensuring that polls serve as a reliable barometer of public opinion rather than a weapon of persuasion.

Is Amazon a Political Stock? Analyzing Its Influence and Implications

You may want to see also

Response Bias: How non-response or selective participation distorts poll outcomes and objectivity

Political polls are often touted as snapshots of public opinion, but their accuracy hinges on a critical assumption: that those who respond are representative of the entire population. Response bias, however, undermines this assumption. This occurs when certain groups are systematically over- or under-represented due to non-response or selective participation. For instance, older adults are more likely to answer phone surveys than younger individuals, skewing results toward their preferences. Similarly, highly opinionated individuals may be more motivated to participate, amplifying extreme views. This distortion isn’t just theoretical; a 2016 U.S. presidential poll missed the mark because it over-sampled college-educated voters, who leaned Democratic, while underestimating less-educated voters, who favored Trump. Such biases render polls less objective, turning them into reflections of specific demographics rather than the broader electorate.

To mitigate response bias, pollsters must first identify who isn’t participating and why. Non-response rates—the percentage of people who refuse or ignore surveys—are a red flag. For example, a Pew Research study found that only 6% of Americans typically respond to phone surveys, with younger and minority groups disproportionately absent. This creates a self-selection problem: those who do respond often share similar traits, such as higher education levels or stronger political engagement. Pollsters can counteract this by using weighted adjustments, where responses are statistically rebalanced to match demographic benchmarks like age, race, and education. However, this method assumes the missing groups would have answered in predictable ways, which isn’t always accurate. Without addressing non-response directly, even weighted polls risk misrepresenting public opinion.

Consider the practical steps pollsters can take to reduce response bias. Mixed-mode surveys—combining phone, online, and in-person methods—can reach diverse populations. For instance, younger voters are more likely to respond to text-based surveys, while older adults prefer phone calls. Offering incentives, such as small cash rewards or gift cards, can also boost participation across demographics. Another strategy is panel surveys, where the same group is repeatedly polled over time, reducing the impact of one-time non-response. Yet, these methods aren’t foolproof. Incentives might attract only those who need the reward, and panels can still suffer from attrition. The key is transparency: pollsters must disclose their methods and limitations, allowing audiences to interpret results critically.

A comparative analysis reveals that response bias isn’t unique to political polls. In medical research, for example, non-response can lead to overestimating treatment efficacy if healthier individuals are more likely to participate. Similarly, in market research, affluent consumers may dominate surveys, skewing product feedback. The takeaway? Response bias is a universal challenge, but its impact on political polls is particularly consequential. While medical studies can rely on controlled trials, and market research can use sales data as a reality check, political polls have no such fallback. Their objectivity depends entirely on representative participation, making response bias a critical flaw that demands constant vigilance and innovation.

Mastering Corporate Politics: Strategies for Influence and Career Advancement

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, political polls are not always objective. Their objectivity depends on factors like question wording, sample selection, and methodology.

Yes, biased or leading questions can skew responses, making the poll less objective and more aligned with a particular viewpoint.

Not always. If certain groups are underrepresented or excluded in the sample, the results may not be objective or reflective of the entire population.

Yes, pollsters with ties to political parties or special interests may introduce bias, raising questions about the objectivity of their findings.

Yes, polls conducted during highly charged political events or immediately after significant news may capture temporary sentiments rather than objective, long-term opinions.