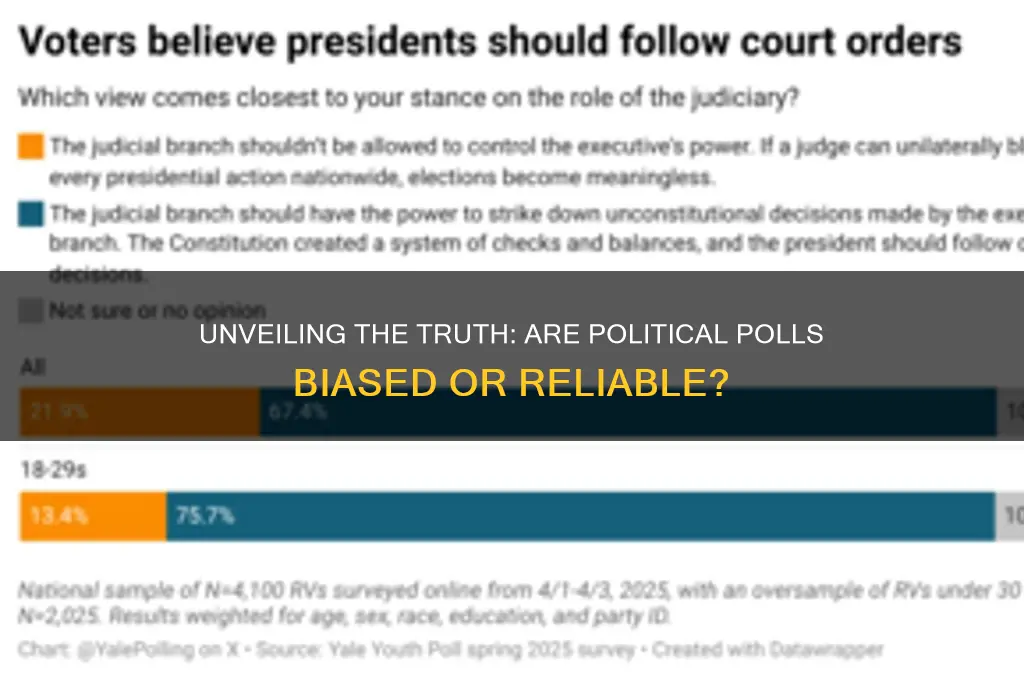

Political polls, often seen as a barometer of public opinion, have become a cornerstone of modern political discourse, yet their accuracy and impartiality are frequently called into question. Critics argue that polls can be inherently biased due to factors such as sample selection, question wording, and the timing of surveys, which may disproportionately favor certain demographics or viewpoints. Additionally, the increasing polarization of media and the rise of partisan-aligned polling organizations further complicate their reliability. Proponents, however, contend that when conducted rigorously and transparently, polls can provide valuable insights into public sentiment. The debate over whether political polls are biased highlights broader concerns about the role of data in shaping political narratives and the challenges of capturing a truly representative snapshot of public opinion.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Media Influence on Poll Results

Media outlets often shape public perception by selectively reporting poll results that align with their narratives, amplifying certain findings while downplaying others. For instance, a poll showing a 5-point lead for a candidate might be headlined as "Candidate A Surges Ahead," even if the margin of error is ±4%, rendering the lead statistically insignificant. This framing can create a bandwagon effect, influencing undecided voters to align with the perceived frontrunner. To avoid being misled, readers should scrutinize headlines for sensationalism and cross-reference multiple sources to verify the context and reliability of reported poll data.

The timing of poll releases is another critical factor in media influence. Strategic publication dates can sway public opinion during pivotal moments, such as debates or scandals. For example, a poll released immediately after a candidate’s gaffe might exaggerate its impact, while one released during a news lull could be overlooked. Media organizations often capitalize on this by timing releases to maximize viewership or readership, prioritizing engagement over impartiality. To counter this, audiences should note the poll’s field dates and compare them to recent events, ensuring they understand whether the results reflect current or outdated sentiments.

Poll questions themselves can be crafted to elicit specific responses, a tactic media outlets may exploit to support their agendas. Leading questions, loaded language, or biased response options can skew results in favor of a particular outcome. For instance, asking, "Do you support Candidate B, who has been accused of corruption?" introduces a negative bias. Media outlets might then report these skewed results as fact, shaping public discourse unfairly. To evaluate poll integrity, examine the question wording and methodology—reputable polls use neutral language and balanced response options.

Finally, the media’s tendency to oversimplify complex poll data can distort public understanding. Reducing a poll to a single headline figure, such as "52% Support Policy X," ignores nuances like demographic breakdowns, sample size, or confidence intervals. This oversimplification can mislead audiences into believing the results are more definitive than they actually are. To gain a fuller picture, seek out detailed poll reports that include cross-tabs and methodological notes. Understanding these components allows for a more informed interpretation of the data, reducing the media’s ability to manipulate perceptions through selective presentation.

Technology's Political Nature: Power, Control, and Societal Impact Explored

You may want to see also

Sampling Methods and Bias

Political polls are only as reliable as the samples they draw from. A poll claiming to represent the entire electorate but based on a skewed sample is essentially a house built on sand—unstable and untrustworthy. Sampling bias occurs when the selected group doesn't accurately reflect the population being studied, leading to misleading conclusions. For instance, a phone survey that relies solely on landlines will underrepresent younger voters who predominantly use mobile phones, potentially skewing results in favor of older demographics.

Consider the 2016 U.S. presidential election, where many polls predicted a Hillary Clinton victory. Post-election analyses revealed that some polls oversampled college-educated voters and undersampled white working-class voters, a demographic that heavily favored Donald Trump. This sampling error contributed to the unexpected outcome, highlighting the critical need for representative samples. To avoid such pitfalls, pollsters must employ rigorous sampling methods, such as stratified sampling, which divides the population into subgroups (e.g., by age, race, or region) and ensures each subgroup is proportionally represented.

However, even stratified sampling isn't foolproof. Response bias, where certain groups are more likely to participate in polls, can still distort results. For example, individuals with stronger political opinions may be more inclined to respond, while apathetic voters remain silent. Pollsters can mitigate this by using weighting techniques, adjusting the sample to match known demographic distributions. Yet, this requires accurate census data, which isn’t always available or up-to-date. Practical tip: When interpreting polls, look for transparency in methodology—how was the sample collected, and what adjustments were made?

Another challenge is non-response bias, where some individuals refuse to participate. In 2020, Pew Research found that response rates for phone surveys had plummeted to just 6%, raising concerns about representativeness. To combat this, some pollsters use multi-mode approaches, combining phone calls, online panels, and mail surveys to reach a broader audience. For instance, a poll targeting 18–24-year-olds might prioritize social media and text-based surveys, while older demographics may respond better to phone calls. Caution: Multi-mode sampling increases complexity and cost, requiring careful calibration to avoid over-representing tech-savvy respondents.

Ultimately, the key to minimizing sampling bias lies in diversity and diligence. Pollsters must continuously refine their methods, leveraging technology and demographic data to capture the full spectrum of public opinion. For consumers of political polls, skepticism is healthy. Question the sample size, the response rate, and the weighting adjustments. A poll claiming 95% accuracy with a margin of error of ±3% is meaningless if the sample itself is flawed. Takeaway: Sampling methods are the backbone of polling accuracy, and understanding their limitations is essential for interpreting results critically.

Hamilton's Political Impact: Analyzing the Revolutionary Musical's Message

You may want to see also

Question Wording Effects

The way a question is phrased in a political poll can significantly alter the responses, often leading to biased outcomes. Consider the following example: a poll asking, "Do you support the government's plan to increase taxes on the wealthy?" may yield different results compared to, "Do you think the wealthy should pay their fair share in taxes?" The former frames the issue as a government initiative, potentially triggering partisan reactions, while the latter appeals to a sense of fairness, which may resonate more broadly. This subtle difference in wording can sway public opinion, highlighting the critical role of question design in polling accuracy.

To mitigate bias from question wording, pollsters should adhere to specific guidelines. First, use neutral language that avoids leading or emotionally charged terms. For instance, instead of asking, "Should we stop the reckless spending on social programs?" rephrase it to, "What is your opinion on current government spending on social programs?" Second, ensure questions are clear and unambiguous. Vague or complex phrasing can confuse respondents, leading to inconsistent answers. For example, avoid jargon or technical terms that may not be universally understood, such as "Do you support the implementation of a carbon tax to mitigate climate change?" without defining "carbon tax."

A comparative analysis of polls on the same topic but with different question wordings can reveal the extent of bias. For instance, a study on public opinion about healthcare reform found that polls using the term "Obamacare" received more negative responses than those using "Affordable Care Act," even though they refer to the same policy. This demonstrates how labels and framing can influence perceptions. Pollsters must be mindful of such effects and strive for consistency in terminology to ensure comparability across surveys.

Practical tips for respondents can also help counteract question wording effects. Encourage participants to read questions carefully and consider the intent behind the wording. If a question seems biased or unclear, respondents should feel empowered to ask for clarification or provide additional context in their answers. Additionally, being aware of one's own biases and trying to answer objectively can improve the reliability of poll results. For example, if a question about immigration policy feels loaded, take a moment to reflect on personal beliefs versus the question's intent before responding.

In conclusion, question wording effects are a significant source of bias in political polls, but they can be managed through careful design and awareness. Pollsters must prioritize neutrality, clarity, and consistency in their questions, while respondents should approach surveys critically and thoughtfully. By addressing these issues, we can enhance the accuracy and reliability of political polling, ensuring it serves as a true reflection of public opinion rather than a manipulation of it.

Mastering the Art of Polite RSVP: Etiquette Tips for Every Occasion

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$15.03 $26.99

Timing of Polls Impact

The timing of political polls can significantly sway public perception, often in ways that are subtle yet profound. Consider the release of a poll just days before an election: it can either solidify a candidate’s lead, encouraging complacency among supporters, or galvanize undecided voters to rally behind an underdog. For instance, a 2016 U.S. presidential poll released 48 hours before Election Day showed Hillary Clinton with a 3-point lead, potentially lulling her base into a false sense of security. Conversely, a poll showing a tight race might spur last-minute campaigning efforts, altering the outcome. This demonstrates how timing isn’t just about when data is collected, but when it’s disseminated.

Analyzing the impact of timing requires understanding the poll’s shelf life. A survey conducted six months before an election may reflect public sentiment at that moment but becomes less relevant as events unfold. For example, a poll taken before a major policy announcement or scandal will fail to capture the shift in public opinion that follows. Pollsters must balance the need for timely data with the risk of obsolescence. A practical tip for consumers of polls: always check the field dates. A poll conducted last month might not reflect today’s political climate, rendering its findings outdated.

To mitigate timing bias, pollsters employ rolling averages, which aggregate data over a set period (e.g., 7 days) to smooth out daily fluctuations. This method provides a more stable snapshot of public opinion, reducing the impact of short-term events. However, even rolling averages have limitations. For instance, during fast-moving crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, public sentiment could shift dramatically within days, rendering a 7-day average less accurate. Poll consumers should look for methodologies that account for volatility, such as weighted averages or real-time adjustments.

Comparatively, the timing of polls in different electoral systems highlights their varying impacts. In countries with shorter campaign periods, like the UK, polls taken weeks before an election can still be highly influential. In contrast, the U.S.’s lengthy campaign cycle means polls must be interpreted with greater caution, as months of campaigning can alter dynamics. A 2019 UK poll showing Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party with a 10-point lead solidified his position, while a similarly timed U.S. poll might have been overshadowed by subsequent debates or scandals. This underscores the importance of contextualizing timing within the specific electoral landscape.

Finally, the strategic release of polls by campaigns or media outlets can manipulate public discourse. A campaign might delay releasing unfavorable results or rush to publish positive ones to shape narratives. For instance, a poll showing a candidate’s surge in popularity might be released just before a fundraising deadline to boost donations. To avoid being misled, always cross-reference polls from multiple sources and scrutinize the sponsoring organization’s motives. A useful rule of thumb: trust polls from non-partisan organizations with transparent methodologies over those tied to political interests. Timing isn’t just a logistical detail—it’s a tool that can either illuminate or distort reality.

Mastering the Art of Pitching Politico: Tips for Success

You may want to see also

Political Affiliation of Pollsters

The political leanings of pollsters can subtly influence polling outcomes, often through methodological choices rather than overt bias. Pollsters affiliated with a particular party or ideology may unconsciously frame questions, select samples, or weigh data in ways that favor their preferred narrative. For instance, a pollster might over-represent urban voters in a sample, inadvertently skewing results toward more liberal outcomes. This isn’t always malicious but highlights how personal beliefs can seep into the technical process of polling.

Consider the steps involved in polling: question design, sample selection, and data weighting. Each step offers opportunities for bias, intentional or not. A pollster sympathetic to a conservative agenda might phrase a question about taxation in a way that emphasizes burden rather than benefit. Conversely, a liberal-leaning pollster might highlight social services when asking about government spending. These nuances can shift public perception, even if the pollster believes they’re being neutral.

To mitigate this, examine the affiliation of the polling organization, not just the pollster. Organizations like Rasmussen Reports have been criticized for a perceived conservative tilt, while others like Pew Research Center are often seen as more neutral. Cross-referencing polls from multiple sources can help identify outliers and reveal potential biases. For example, if one poll consistently shows a candidate leading by a wide margin while others show a tighter race, scrutinize its methodology and the political leanings of its sponsors.

Practical tip: Look for transparency in polling reports. Reputable pollsters disclose their methodologies, including how they select and weight samples. If an organization doesn’t provide this information, treat its results with skepticism. Additionally, consider the funding source. Polls funded by political parties or advocacy groups are more likely to reflect the biases of their backers. Independent, non-partisan organizations are generally more reliable, though no poll is entirely immune to bias.

In conclusion, while the political affiliation of pollsters isn’t the sole determinant of bias, it’s a critical factor to consider. By understanding how personal and organizational leanings can influence polling, you can better interpret results and avoid being misled. Always approach polls critically, and remember: the devil is in the details.

Philosophy's Impact: Shaping Political Thought, Action, and Governance Today

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political polls are not inherently biased, but they can be influenced by factors like question wording, sample selection, and timing, which may skew results.

Yes, biased or leading questions can influence responses, making it crucial for polls to use neutral and clear language to ensure accuracy.

Polls themselves do not favor any side, but biases can arise from how data is collected, weighted, or interpreted by pollsters or media outlets.

Yes, some groups, like young voters or minorities, may be underrepresented due to lower response rates or inadequate sampling methods, affecting poll accuracy.

While polls are often reported objectively, media outlets may emphasize certain findings or frame results in ways that align with their narratives, creating perceived bias.